|

India is the seventh largest country in the world in terms of geographic landmass, and the second largest in terms of population – with 1.2 billion people. When gross domestic product is considered, the country falls into the ten largest economies. Further, the country has been experiencing economic growth of around 7% per annum since 2000, despite the 2008 economic crisis. The country enjoys an abundance of traditional and non-traditional energy sources, but these sources are insufficient to meet India’s growing needs. It therefore resorts to importing most of its energy from abroad, especially from Middle East crude oil and natural gas exporters.

India’s energy quandary is illustrated by the statistic that, in 2011, it was the fourth largest energy consumer after the United States, China and Russia. Furthermore, despite average per capita consumption in India remaining low relative to that of western countries, the growth in energy use has meant that the country’s consumption levels have doubled since 1990. Making this situation even direr is the estimate that over 44% of Indian homes do not receive electricity and more than 90% of them rely on biomass such as wood, waste and gas.

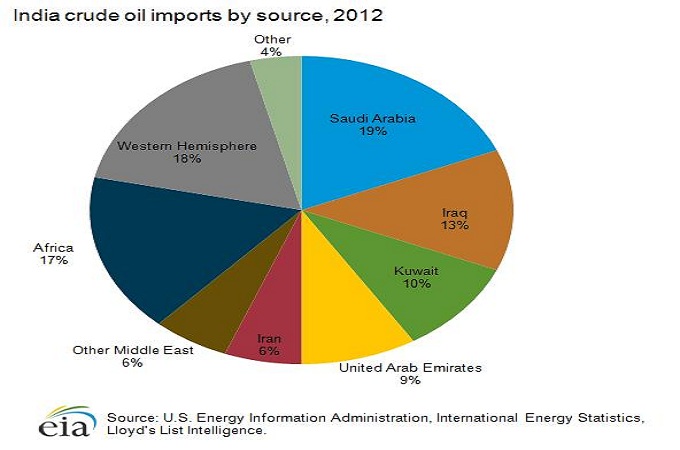

Meeting the growing demand for energy is a major challenge that is constantly confronting Indian leaders. The country has crude oil imports from around 40% in 1990 to 70% in 2011. In 2012, over 64% of these imports came from the Middle East, a trend that is expected to continue. By 2032, over 91% of the country’s energy needs will need to be imported. Thus, in an effort to secure both best prices and energy security, the country has concluded a number of short- and long-term contracts at government level and, to a lesser extent, through private companies.

However, despite the country’s dependence on the Middle East for the provision of this vital and strategic resource, no clear political, economic, or even energy policies directed at the region have been formulated. The establishment of diplomatic relations with Israel in 1992 marks one of the clearest and most important turning points in India’s interaction with the region. These relations have flowered and now encompass both the strategic and security realms. When it began, the relationship was opposed by the country’s Muslims and leftists, and was met with moderate protests from Arab states. At the core of these relations was the perception within part of the Indian ruling elite that the country’s strong pro-Arab stance was not being reciprocated with support for Indian claims over Kashmir.

Although India has not yet clearly determined its goals in the Middle East, it is slowly treading a path that will eventually lead to a clearly defined role in the region. The most significant step in this regard was the country’s May 2005 appointment of an ambassador extraordinary and plenipotentiary to the region. This was followed by the 2006 naval entrance into the area to supplement diplomatic efforts. So far, India’s navy has conducted exercises with countries including Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Bahrain, Qatar, and the United Arab Emirates. An important characteristic of Indian diplomacy has been its ability to maintain amicable relations with countries that oppose each other, such as Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Israel. It is significant that India still maintains strong relations with Iran, despite ongoing US pressure to revaluate this relationship.

Energy Sources

India enjoys a number of energy sources: non-renewable energy such as coal, lignite, oil and natural gas; and renewable energy such as wind, solar energy, hydropower, biomass, and sugarcane bagasse. Knowing the size and amount of these sources is necessary to assess the extent of the country’s need for consumable and imported energy, and develop strategies to secure the required energy from external sources. India is trying hard to develop alternative local sources to meet the energy challenge and reduce its dependence on external sources.

Local Reserves

On 31 March 2011, India’s coal reserves were estimated at 286 billion tons, and its lignite at 41 billion tons. In March 2011, its estimated oil and natural gas reserves amounted to 757 million tons and 1,241 billion cubic metres respectively. Some 43% of India’s oil reserves are in fields off the western coasts, and 22% in the Assam fields of northwest India. Of its natural gas reserves, 35% is in fields off the eastern coast, and 33% in fields off the western coasts. The size of the renewable energy was estimated at 89,760 megawatts on 31 March 2012, and was divided as follows:

- Wind energy: 49,132 MW (55%);

- Small hydro-energy sources: 15,358 MW (17%);

- Biomass: 17,538 MW (20%); and

- Sugar cane bagasse: 5,000 MW (6%).[1]

Potential for Generating Electric Power

As of 31 March 2013, the potential for energy generation amounted to 206,526 megawatts, compared to 16,271 MW on 21 March 1971, representing an increase of 6.4% per annum. About 64% of this is expected to be provided by thermal electric generating stations and 18.2% is to be acquired from hydro-electric stations. The electricity production of nuclear powered plants did not exceed 2.31% in 2011.

Coal is currently the traditional source of power generation in India, but due to the low quality of local coal, it is imported from Australia and Canada. Coal imports have increased from 20.93 million metric tons in the 2000-01 period to 73.26 million metric tons in 2009-10. During the same period, domestic coal exports increased from 1.29 million to 2.45 million metric tons. However, the importation of coal witnessed a 59.2% decline in 2010, while coal exports increased by 80%.[2]

India relies heavily on imported crude oil and its derivative petroleum products to meet its growing needs. Imports have been increasing year after year. Imports jumped from 11.68 million metric tons in 1970-71 to 163.59 million metric tons in 2010-11. The 2010-11 period witnessed an increase of 2.72% over the previous year. India currently imports about 70% of its crude oil and petroleum products from countries across the world.

There are 20 oil refineries in India, 17 of which are owned by the public sector with the remaining three owned by private entities. By 31 March 2011, the total annual capacity of these refineries was 187 million metric tons. The refineries had been operating at 105.7% of their capacity in 2009-10 and at 110% during the 2010-2011 year.[3] The country has, in recent years, succeeded in setting up facilities for refining and processing crude oil and its derivatives, to the extent that it now is an exporter of oil products. Its oil derivatives increased from 0.33 million tons in 1970-71 to 59.13 million tons in 2010-11. These statistics are even more astounding when we note that the 2010-11 figure represents an increase of 16% over the 2009-10 figure.

Further, the country has the fifth largest wind electricity generation network in the world. Its generation capacity currently stands at over 11,800 megawatts, and solar energy generation targets have been set at 20,000 megawatts for 2022.

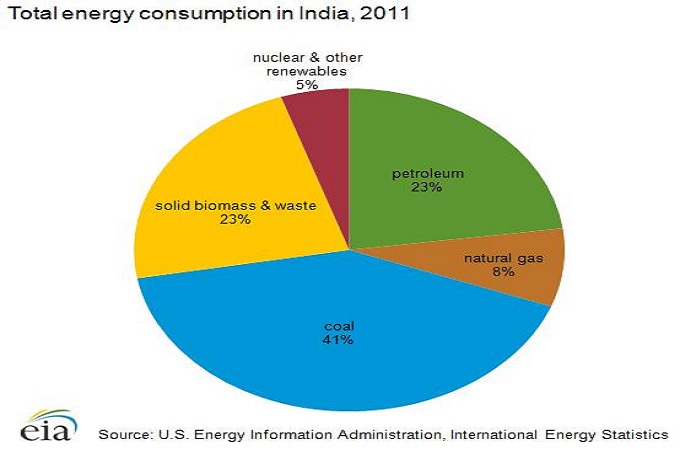

Crude Oil Production and Consumption

India is currently responsible for around 1% of total crude oil production, which in 2010-11 was calculated at 38.9 million tons.[4] However, in the same period, the country consumed 155.5 million tons of crude, representing 3.9% of global production for that year.[5] And, in the 2010-11 period, India produced 1.6 per cent of global natural gas production (45.8 million tons).[6] Over 70% of India’s energy usage is currently comprised of fossil fuels. Coal represents around 40% of this whilst 2.4% is made up of crude oil, with natural gas constituting 6%. These figures illustrate the dilemma of power in India, which can be summarised as an increasing shortage of energy products and the relentless attempt to source the shortfall from alternative and renewable sources – specifically solar, nuclear and wind energy.[7]

Sources of Indian crude oil imports

|

|

India hopes to attain, by 2032, 25% energy self-sufficiency through the use of renewable sources, and has already enacted various laws to enable this. For this purpose, the state established a ministry of renewable energy in 1992. Furthermore, it has encouraged and provided incentives for energy produced from waste, solar projects and wind energy. Companies have been incentivised to produce renewable energy through ‘green energy’ financial bonds, customs duty reductions on imported equipment for renewable energy generation, and the provision of soft loans and financial concessions. These incentives aim to increase especially water, wind and solar capacities. Undoubtedly, the country seeks to reduce the cost gap between traditional energy generation and renewable energy. The construction of green buildings to reduce the country’s overall energy consumption is also encouraged.

Although India is a major importer of crude oil, it is also a huge exporter of refined oil. It has established a number of refineries for this purpose, especially in Gujarat. Two companies, Essar Oil and Reliance, export naphtha, benzene and refined petroleum products to Singapore, the United Arab Emirates, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, Iran and other countries. Petroleum products are also exported to the US market by Reliance Group.

Needs

By 2025, India will be the second largest pressure, after China, on global energy resources.[8] The country is trying to respond to this through two ways: by expanding the base of domestic renewable energy and increasing its nuclear power capacity which is scheduled to rise to 9% of total energy capacity in the next 25 years from its current 4.2% level. India has five nuclear reactors, and is working to build 18 more by 2025. If this is achieved, the country will have the highest amount of energy nuclear reactors in the world. The seriousness of India’s energy requirements can be gleaned from the fact that over 56% of rural households receive no electricity.[9]

Foreign investment

Besides expanding the power network internally, India has sought partnerships with both foreign governments and companies, and exploration rights abroad. The government encourages its departments and private companies to acquire exploration and production rights abroad as a way to protect the domestic market from international price fluctuations. It has achieved these gains despite opposition from the United States.[10]

India has, thus far, acquired rights in over 24 countries. The government-owned Oil and Natural Gas Corporation Limited (ONGC) alone has invested 11 billion dollars in such contracts, and currently has a presence in 15 countries where it is involved in over 40 projects. Countries where the ONGC is active include Vietnam, Russia, Sudan, Myanmar, Colombia, Cuba, Syria, Iran, Iraq, Libya, Brazil, Venezuela and the joint development zones between Nigeria and São Tomé, and Principe, Nigeria and Egypt. Reliance has been involved in the purchase of US shale natural gas project rights. Likewise, private companies such as Hindustan Petroleum, Essar and Bharat Petroleum have undertaken similar activities. The Indian government is vigorously seeking more opportunities and Indian embassies are tasked with this responsibility.[11]

India has also decided to invest in the Israeli energy sector. It has invested an unknown amount in the Leviathan natural gas field, located in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. Kuwaiti protests, interpreted as being orchestrated by Saudi Arabia, have failed to force India to alter this policy.[12]

In the context of energy provision and diversification of energy sources, India has signed the Trans-Afghanistan Pipeline (or the Turkmenistan–Afghanistan–Pakistan–India Pipeline, TAPI) Treaty, which will run from Turkmenistan through Afghanistan and Pakistan. It has not yet signed the treaty for the Iranian gas pipeline that passes through Pakistan. Indian authorities argue that this is mainly a result of security concerns and the fear that Pakistan may exploit the situation during crises. However, it has more to do with US opposition and the threat of sanctions, which have dissuaded India from signing onto a project which would go a long way in solving the current and expected future energy crises and provide it with natural gas at lower prices and better terms then current international prices. India’s November 2009 vote against Iran at the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) almost destroyed its relations with the Islamic republic, halting pipeline negotiations. Amends were made by India, reviewing its stance and adopting a neutral position.

American threats have also led to the reduction of India’s imports of Iranian crude oil from 18.1 million tons in the past year to 13 million tons in the current year. This quantity is transported via oil tankers to India’s western shores.[13] It has refused to fully comply with US pressure which demands that it does not import any oil or gas from Iran. In addition, India has used creative means, including non-dollar payments and barter exchanges, to circumvent US bank sanctions on Iran, and has even created a 3.7 billion dollar insurance fund through its General Insurance Corporation to insure Iranian oil and gas tankers which western insurers have been prohibited from ensuring.

Reducing Dependence on the Middle East

India is currently trying hard to reduce its dependence on Middle East sources, mainly as a result of political instability. It has been attempting to compensate through energy procurement from other internal and external sources, e.g. by investing in fields outside the Middle East and improving relations with neighbouring Myanmar. India has also allowed for ONGC and Reliance's extensive oil exploration, specifically on its coasts. In addition, foreign companies, including Canadian company Kern, have been allowed to explore for oil, especially in the desert state of Rajasthan, which is similar to Arab countries that produce oil, and the Krishna Godavari Basin in South India as well as areas in north-east India, around the state of Assam, where oil was discovered in 1889.

With the exception of Israel, India is uninterested in pursuing a strategic alliance or even close cooperation with any Middle Eastern country, including Iran. Since adopting a policy of economic liberalisation in 1992, under the control of then economic adviser to the central Indian government and now prime minister, Manmohan Singh, India has attempted to become close to western countries, especially the United States and Israel. It has thus sought harmony and coordination with these countries’ policies in terms of politics and security. Its previously strong and longstanding relations with Arab countries such as Egypt have been downgraded. This was best demonstrated by India’s coldness during Egyptian President Mohamed Morsi’s official visit to New Delhi in March. It was clear during the visit that India was not interested in rekindling its relations with the countries with which it once led the Non-Aligned Movement. India had also previously enjoyed close relations with former Iraqi President Saddam Hussein. Saddam sold oil to India at lower prices and with preferential conditions.[14] However, in 2003, when the United States invaded Iraq, India was ready to deploy a large military contingent to join the US-led coalition. It did not join the coalition only because of the huge pressure from the public, opposition parties, and Indian Muslims. In 2006, the government also replaced its oil minister, Mani Shankar Aiyar, who was enthusiastic about the Iranian gas pipeline and wanted close relations with Arab countries, with pro-American Murli Deora.

India’s strong and strategic relations with Israel is due to the belief of many members of the Indian ruling elite that the Jewish lobby in Washington is an important entrance point for influencing American decisions. India believes that good relations with the United States are the key to good relations with Arab Gulf states. In addition, the country has attempted to initiate free trade treaties with some Arab countries but these attempts have, for the most part, been unsuccessful – except for the August 2004 economic cooperation treaty signed with Gulf Cooperation Council countries. However, this treaty, rather than being a practical treaty on economic cooperation, is more of a goodwill document.[15]

Hundreds of Indian companies have, however, opened representative offices and warehouses for their goods in the GCC, and some Indian companies have established projects in the Egyptian free zones. Last March, India signed a joint venture treaty paving the way for the establishment of a solar energy generation project in the Egyptian oasis of Siwa. A key outcome of the treaty was the attempt to illuminate an Egyptian village in the Matrouh governorate through solar energy as an initial pilot project. India has also established a fertiliser plant in Oman to exploit gas resources.

Potential for Cooperation

Due to the geographic proximity between India and many Middle East countries, located just three to four hours away by air, there is great potential for cooperation. However, the indifference of both sides has led to the loss of many opportunities. Arab countries have not realised India’s full potential and only in the last few years have they acknowledged the country – mainly as a result of western media reports around the many leaps in the country’s information technology sector and its status as an emerging power. In an attempt to secure closer economic and industrial relations between the two countries, the January 2006 visit of Saudi Arabia's King Abdullah to India, raised hopes but has not borne any fruit. Saudi Arabia has invested much in India, but only a few sectors.

India remains a non-preferred destination for Arab investments, which commenced about a decade ago when Arab investors reoriented towards the east, specifically toward India. However, the country’s many administrative complexities, lack of clear legislation, and rampant corruption at all levels have greatly inhibited a substantial flow of Arab investments. Arab investment remains light, including Saudi Arabia’s five oil refinery investments through the state-owned Aramco.

Similar problems exist with Indian investments in Arab countries, especially in the oil, gas and industrial sectors. Indian companies, both government and private, do not feel welcome in Arab countries, believing that these countries are more likely to align themselves with Pakistan. The clearest evidence of this is India’s exclusion from membership in the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) as a result of Pakistani objections, despite the existence of 180 million Muslims in India, who represent the second largest Islamic bloc in the world after Indonesia.

Recently, India has sought security relations with countries in the region within the framework of the fight against terrorism and organised crime, and concluded an extradition treaty with the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia. It also participated in a 2004 Saudi conference on terrorism, and has supported the Saudi proposal for the establishment of a regional centre for combating terrorism.

Axes of Indian Politics in the Middle East

The most pertinent factors influencing Indian interests in the Middle East revolve around four axes:

- Continued access to crude oil and natural gas at lower prices and better payment terms whenever possible. India believes conditions in the Middle East are likely to improve in its favour and that the ‘liberation’ of the United States from dependence on Middle Eastern oil as a result of expansion in US production of natural gas will create a new geopolitical situation in the region. Shivshankar Menon, India’s National Security Adviser, expressed this sentiment in a speech to the Indian Council for Energy, the Environment and Water in August 2012. "The Middle East now counts for less sources of energy," he said. This has made it easier, he added, for the world to bear the current crisis in the Middle East. Also, the energy crisis, which had been predicted as a result of the Arab Spring and the impasse of the Iranian nuclear programme, did not materialise. However, he added, if all energy sources were activated, the world could witness an energy glut similar to that of the 1980s.[16]

- India is always looking for opportunities to participate in energy exploration as is the case in Iraq, Libya and Sudan. Many of these efforts have, however, met US opposition.

- Indian policy aims to secure Arab markets for Indian goods. This is mainly because Arab countries, especially in the Gulf, are large importers of Indian-manufactured goods. The UAE is currently the largest importer of Indian goods in the Gulf, with these subsequently being distributed to Arab, Iranian and African markets. The volume of Indian trade with the UAE stood at 8 billion dollars in 2006. India is also the fourth largest trading partner for Saudi Arabia; however, this trade mainly consists of oil imports as the kingdom is India’s largest oil supplier.

- India regards caring for and protecting the interests of Indian workers in the Middle East as one of its priorities. It is keen that the region, and especially the Gulf states, continues to provide employment for millions of Indians, skilled and unskilled. There are at least 3.5 million Indian workers in the Gulf who remit large sums of money to India (6 billion dollars in 2006). This provides the largest source of hard currency to the country, and is both politically and economically cheap as no special demands are made by these workers to the state.

News this April that thousands of Indians will be deported from Saudi Arabia as a result of the kingdom’s ‘saudiisation’ regulations and the tightening of labour regulations shook both the Indian government and its people. The Indian government intervened at the highest level in Saudi Arabia, and secured a two-month grace period for violators to take corrective measures.

Despite the fog surrounding India’s policy towards the Middle East, it can be concluded that the country has adopted two principles: first, maintaining India’s energy security, that is, guaranteeing India’s access to its oil and natural gas needs without interruption and at the best prices and terms possible; and second, a continuation of Nehru’s policy, which specifies non-interference in the internal affairs of other countries. This policy is likely to be altered in the future, however, when India’s geopolitical position changes as a result of its economic growth. It is expected that India and China will both gain a great deal of influence in the region at the expense of the United States, whose lack of future oil dependence on the region will mean that it will retreat. It will be in the interests of the countries of the region to establish close relations with both emerging powers so that neither one of them does not control the important resources of this region.

* Dr Zafar al-Islam Khan is an Indian journalist and researcher.

[1]Energy Statistics 2012 (Official Indian release), http://mospi.nic.in/mospi_new/upload/Energy_Statistics_2012_28mar.pdf.

[2] Ibid, p 42.

[3] Ibid, p 18.

[4] Ibid, p 81.

[5] Ibid, p 83.

[6] Ibid, p 86.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Venu Rajamony, Joint Secretary for Energy Security in the Indian Ministry of External Affairs, speaking to Knowledge @ Wharton, Sept 2010, http://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/arabic/article.cfm?articleid=2533.

[12] Kabir Taneja, ‘India’s stake in the Middle East,’ Tehelka Magazine, 22 March 2013, http://blog.tehelka.com/indias-stake-in-the-middle-east-2/.

[13] The Pioneer, Delhi, 8 April 2013.

[14] This was revealed by American documents released by WikiLeaks in early April 2013, which said that Saddam Hussein sold oil to India at a price of $8.5 per barrel in 1974, while the market price was ten dollars a barrel: Times of India, Delhi, 10 April 2013.

[15] See the text of the document: http://www.eximguru.com/exim/trade-agreement/framework-agreement-with-g….

[16] Indrani Bagchi, ‘Less dependence on Middle East energy to impact geopolitics: national security advisor,’ Times of India, 25 August, 2012.