The international conference “Shaping a New Balance of Power in the Middle East: Regional Actors, Global Powers, and Middle East Strategy”, co-hosted by Aljazeera Centre for Studies (AJCS) and John Hopkins University (JHU) in Washington earlier this summer, has triggered wider debate about the nature and the promise of an emerging balance of power in the region. New questions are raised about how a new balance can be different from the traditional U.S.-Soviet politics of bipolarity and rival proxies, the impact of new players, the power of militant groups and other non-state actors, and whether any emerging balance of power can be sustainable in the future. For instance, the Gulf and the Middle East are suffering a paroxysm of conflict involving virtually all the regional states as well as the US and Russia and many different non-state actors. What dynamics are driving this chaos? What can be done to contain or reverse the damage? How might a new balance of power emerge?

As part of a special series “Shaping a New Balance of Power in the Middle East”, AJCS welcomes the insights of Dr. Kayhan Barzegar who probes into Iran’s foreign policy strategy, how it has enhanced its geopolitical status in the regional balance of power, and how it has adjusted to the changing regional developments.

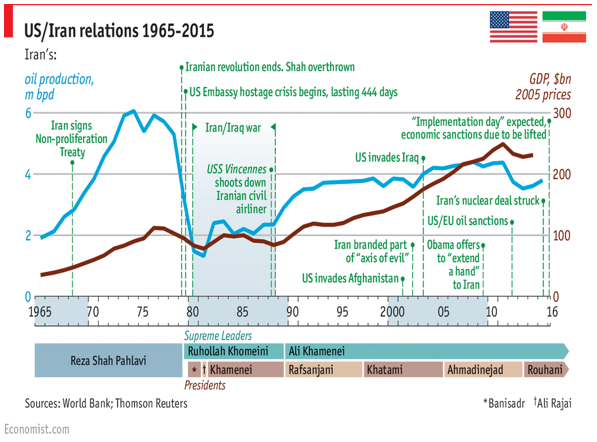

Admiral Ali Shamkhani, the secretary of Iran’s Supreme National Security Council, says, “The negative approach of the others is not due to the threatening nature of Iran’s nuclear, missile and regional activities. Rather, it is due to their opposition to Iran’s emerging power…in this regard, only through producing power [in the region] at the hard and soft levels can country to achieve national and sustainable security.” (1) Indeed, from the perspective of Iranian elites in the realms of government and security, there is a direct relation between Iran’s enhanced national power and the country’s strengthened regional status. This is significant, both in terms of benefiting from Iran’s geopolitical advantages in integrating the country to the regional economy, and tackling the conventional and unconventional threats. Conventional threats relate to the United States, Israel, and, most recently, Saudi Arabia’s regional activities against Iran. Unconventional threats relate to the terrorist activities of ISIS and Al Qaeda-affiliated groups across Iran’s boundaries that endanger Iran’s national security.

In this respect, tendency towards increased regional cooperation has always been strong in Iran’s foreign policy strategy, yet it has been required to balance the other constant of the country’s foreign policy, which is to deter the threats, through hard and soft means, from the region. This situation has led Iran’s regional and international rivals to strongly believe that Iran’s increased regional presence is expansionist and consider it a threat to the current balance of power.

Yet, Iran considers such a presence necessary for tackling the regional problems and the increasing its relative security. Iran also believes that an increased regional connectivity will benefit its economic growth. With the emergence of ISIS and the creation of a regional coalition against Iran, especially after U.S. President Donald Trump unilaterally withdrew the United States from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA)-the Iran nuclear deal- the issue of deterring threats in the region has become more significant in Iran’s foreign policy strategy. In the time of the Islamic Republic, strengthening Iran’s status in the regional balance of power has evolved in three shapes: First, to create the strongest Iran in the region, second, to build Iran in a strong region, and, third, to create a strong Iran from within.

Regional Aims and Principles

Iran is a unique country and has its own way of conducting foreign policy strategy inits geopolitical environment. These characteristics mostly relate to its nation’s historical expectations towards progress and prosperity, the perception of its ruling elites to how to tackle threats, ways to preserve its national and security interests, its geographical situation and energy resources, and its perspective and perception toward the ways others looking at the country and its political system. Apart from all the opportunities, Iran’s geographical (being situated at the center of regional sub-systems and international energy hub) and socio-historical (being Persian and Shiite) considerations will bring the country some strategic constraints such as divergence of interests with other regional and foreign powers to the extent that it needs to continually adjust its policy according to the changing regional politics such as the Arab Spring. For this reason, Iran has often been unable to generalize its foreign policy conduct to the broader regional geopolitics.

To adjust its regional interests, Iran has gradually reached the conclusion that the most effective foreign policy strategy is that the country defines a few macro principles in its conduct and, then based on the characteristics of surrounding sub-region’s geopolitics, balances its foreign policy based on developmental and or political-security and deterrent approach. For instance, Iran’s policy in Iraq and Afghanistan is different from that of Syria or Yemen. This issue becomes more significant when one notes that there is a dominant belief inside Iran that the best situation for a regional balance favoring the country is when the dominant foreign power, the United States, is distant from committing itself to any regional military-security treaty, especially with Arab neighboring countries, whose territories could be used as a base for conducting military operations against Iran. Recently, the conduct of a joint military maneuvering, by the United States, Saudi Arabia, and United Arab Emirates in the Red Sea, was conceived as the start of a possible security alliance, dubbed the “Arab NATO” under the U.S. leadership to counter Iran’s growing presence in the region. (2)

|

| (Sipri) |

Cooperation versus Deterrence

Generally speaking, the region has a specific place in Iran’s foreign policy conduct bringing both opportunities and challenges. On the one hand, it is the base of regional cooperation for the country’s economic growth and development. On the other, it is the main source of both imposing and deterring the threats and creating sustainable security for the country. First, in the realm of economy, there is an emerging view among the Iranian elites that the country’s way to economic growth is to enhance regional connectivity and economic integration with the neighborhood areas.

Given all the emerging discrepancies between Iran and the West, especially after Trump’s withdrawal from the nuclear deal and restoring the sanctions, this orientation has become a priority in the Iranian mindset. The logic for this line of thinking is that Iran’s economic progress could better be achieved through bilateral or trilateral economic settings with neighboring countries and expansion of transportation and financial networks, as well as exchange of national currency and labour force, goods, and capital and national products. In this respect, Iran’s geographical centrality and cultural-socio commonalities with the neighbourhood region could help the country to maximize its exploit of national resource for increased economic growth.

Geographical and historical-cultural determination has situated Iran in the middle of five important sub-regional systems: The Levant, the Caucasus, Central Asia, South Asia and the Persian Gulf. Iran can be the main cross of economic linkage for smaller businesses between the Black Sea ports and the Gulf. The country also has economic and tourist attractions for countries such as Russia, Turkey, the Caucasus countries extending to the western ports of the Black Sea in Bulgaria, Romania and Eastern Europe.

Railroad and pipeline’s connections with Iraq, Syria and Lebanon, reaching to the Mediterranean Sea is another way for economic, cultural-political, and pilgrimage integration. Meanwhile, economic, energy, rail and land exchanges in the Caspian Basin, Central Asia and Afghanistan and their connection with South Asian countries, such as Pakistan and India, together with undertaking bilateral trade with some states in the Gulf, such as Oman, Qatar and Kuwait, which have a moderate approach towards Iran, are all in the context of competent use of the potentials of local economies for Iran’s economic growth.

Second, in the realm of deterrence, the dominant view among the Iranians elites is that way to creating sustainable security is through preempting the threats and enhancing friendly states in the region, especially across Iran’s immediate boundaries. The regional developments after the Arab Spring since 2011 has brought about new geopolitical challenges, such as the emergence of Daesh (ISIS) and increased activities of Al Qaeda affiliate groups. The changing geopolitical environment has intensified the traditional military threats of the U.S. and Israel, for Iran’s national security. These developments have also redefined the role and ambitions of Iran’s regional rivals and friends, such as Saudi Arabia and Turkey, giving new space to states such as United Arab Emirates and Qatar to play in the court of regional geopolitics, especially in Syria, at the expense of Iran.

|

| (John Hopkins University) |

Tackling these threats, Iran has adopted a two-pronged policy: On the one hand and through an assertive policy, it has fought with terrorist groups, such as Daesh, on the fields in Iraq and Syria in order to both secure its borders and avoid any change of the political-security trends, by its regional and trans-regional rivals at the expense of its geopolitical interests. On the other and with constructing a military coalition with Russia, as a superior military power, and combining its military strength, both in the air and the ground, Iran has strived to keep the current political system in Syria intact so that it could weigh the regional balance of power in its own and regional allies’ favor.

Russia’s presence in the regional equations has brought about new dynamics for regional geopolitical environment, consequently enhancing Iran’s playing role in the Geneva peace talks and the Astana Process on the Syrian crisis. This situation has led Turkey to join the Iran-Russian coalition. Russia and Turkey have a nuanced view of the regional dynamics according to their national security and interests and therefore (unlike the U.S. and its regional allies) recognize the legitimacy and necessity of Iran’s role and participation in any regional settings.

Yet, Trump’s policy of re-introducing Iran as the main source of regional instability, supported by Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates and Israel, has complicated the Iranian factor in the regional balance of power, directing the country to focus on the deterrence aspect of its regional policy. Trump withdrew from the Iran’s multi-lateral nuclear deal with world powers to pave the way for imposing new and coercive economic sanctions in order to counter Iran’s regional presence. His main logic is that the nuclear deal has increased Iran’s regional role and influence through accessing the cash which was delivered to Iran as the result the deal by the Obama administration, used by Iran to enhance its regional strength, without changing any of its regional behavior. He believes that the deal acted against the interests of the United States and its regional allies and must therefore be revised.

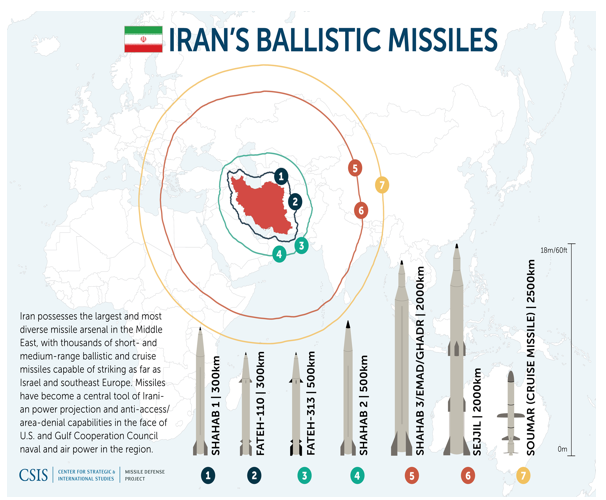

Trump called the nuclear deal “the worst deal ever,” adding new reservations to it, such as the necessity of limiting Iran’s missiles’ program and confining its regional presence, especially in Iraq, Syria and Yemen. Looking carefully at these reservations, one could realize that the main goal of the U.S. President is to weaken the Iranian factor in the regional balance of power.

Iran’s Regional Approaches

In the time of the Islamic Republic, strengthening Iran’s status in the regional balance of power has evolved in three shapes: a) to create the strongest Iran in the region; b) to build Iran in a strong region; and, c) to create a strong Iran from within.

1. The Strongest Iran in the Region

After the 1980-1988 Iran-Iraq war, the issue of preserving regional balance of power from Iran’s perspective was linked more to the concept of construction and development through an accommodative and detent foreign policy especially with regional countries. In this era, Iran needed the transfer of technology and flow of foreign investments in order to implement its process of development and progress, especially in the field of energy. In this context, Iran’s “20-Year Development Vision” was planned and ratified. This document emphasizes that Iran must become “the strongest nation” in the region economically, scientifically, technologically and militarily by 2025. (3)

Although Iran’s main goal in planning this vision was developmental, it has faced rather negative reactions from the regional countries, viewing Iran as a country implementing ambitious plans to change the regional balance of power in its own favor. One perspective inside Iran believes that such description of Iran’s regional status will concern other regional powers about Iran’s increased political-security role at the expense of their own status. (4) This view believes that any scheme of becoming the strongest state in the region by any of the regional country is doomed to fail. Talking on such ambitions is not only the solution to solve any of the regional problems, but any attempt to become a hegemonic power in the region is itself a main source of instability and problem.

|

| (CSIS) |

2. Building Iran in a Strong Region

Iran’s nuclear activities in recent years have led the regional and world powers to believe that the regional balance of power is changing in favor of Iran. Although the conclusion of the nuclear deal in July 2015 solved the issue, Iran’s regional presence, together with the country’s advanced missile program, have prevented any increased regional cooperation and talks between Iran and regional players such as Saudi Arabia. Iran rejects any expansionist plan behinds its missile activity, focusing on its deterrence aspect and arguing that it is mostly due to the country’s sense of insecurity from its regional and trans-regional rivals. The moderate government of Hassan Rouhani maintains that establishing stability and security is critical for encouraging the flow of foreign investments to Iran, which was the main goal behind his technocrat administration in concluding the nuclear deal for lifting sanctions and solving the strategic discrepancies between Iran and the West, especially with the United States.

Avoiding further regional political-security compartmentalization that could lead to increased U.S. involvement in the regional affairs, Rouhani’s pragmatic government has introduced a new regional policy strategy that is “to build Iran in a strong region.” With the focus on reducing tensions with the regional powers, this policy is striving to demonstrate a more balanced regional policy. The new approach entails that none of the main regional players has the capacity of becoming a hegemonic power, (5) as the regional politics will not allow any player such a possibility and that the regional players are incapable to win any game alone or impose their ideals on the regional political-security order. (6)

In this respect, Iran’s announced strategy for maintaining a genuine regional balance of power is defined as, enhancing “efficient states in a stronger region”, instead of becoming “the strongest state in a weak region.” From this perspective, being a “superior power”, in a weak region is neither an honor nor a real solution for solving the regional problems. (7) Rather, it is the source of the problems in the region. Becoming a powerful state in the region significantly relates to becoming a powerful country from inside, as well as the creation of a stabilized region. Only in a stabilized region, a competent government with increased domestic legitimacy, the possibility of becoming an ideal model country outside of national borders and absorbing the others’ respects could be realized. (8) In terms of policy implications, this orientation is seeking to remove regional tensions by not focusing too much on the deterrence aspect of Iran’s foreign policy conduct.(9)

3. Creating a strong Iran from within

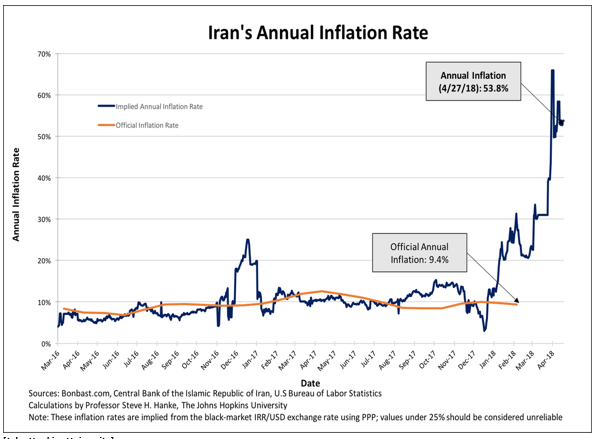

Trump’s withdrawal from the JCPOA and restoring sanctions has brought about new geopolitical constraints, leading Iran to look for a new foreign policy conduct, adjusting its status with the new geopolitical environment and regional balance of power. The JCPOA tried to balance the two dimensions of Iran's foreign policy that is the necessity of regional cooperation to join the international community and absorption of foreign investments through establishing stability in the region on the one hand, and deterring the national security threats from the region on the other. As the complementation of the principles of the JCPOA gradually fails or weakens these days, the deterrence aspect of Iran’s foreign policy is becoming bolder in Iran’s strategic calculus.

It is now more evident for Iran that sticking with a foreign solution (Look to the West or even to the East), due to the JCPOA’s experience, as well as the possibility of reconciliation between the great powers, is rather unlikely to help Iran overcoming its new geopolitical constraints. Meanwhile, Iran's continuous tendency for increased regional cooperation has been interrupted by the Saudis, Emiratis and Israelis, as their prospective goal is to involve the U.S. heavily in the regional affairs, countering Iran's growing regional presence. In such circumstances, although the European governments, Russia and China, are in favour of resisting Trump’s policies, all indicators show that their private sectors’ fear from the U.S. retaliatory acts are forcing them to decrease their economic exchanges with Iran.

|

| [World Bank] |

Inward Looking Strategy

Such possible emerging geopolitical constraints on Iran, have led the Iranian leaders to think of an "inward-looking" strategy, which is primarily based on counting on its own available resources to strengthen a national independent system in economic, political and security sectors. Relying on a strengthening “regional connectivity,” this policy has two aspects:

- Integrating Iran's economy into the neighbourhood’s economy in a bilateral or trilateral context in order to strengthen Iran’s national products, thus processing economic growth, according to the characteristics of local geopolitics.

- Taking advantage of its geographical centrality to enhance its political-security role and influence in the ongoing regional crises in the context of boosting regional multilateralism. This policy could help Iran to add to its strategic value and equate the regional balance of power in its own favor.

In this regard, Iran’s Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif announced that the country’s two super priorities hereafter would be “focusing on economic matters” and “strengthening relationship at the neighborhood realm” and the region. (10) An inward looking policy will also strive to implement an active and interactive foreign policy through linking Iran’s stability to the stability of the region. As already noted, the formation of such a policy is primarily the result of Iran’s attempts to adjust its foreign policy strategy with the changing regional geopolitics.

Adaptability of the New Strategy

There are some reasons to believe that adopting an inward-looking policy could benefit Iran in time of facing geopolitical constraints. First, both Iran and other countries in the region could simultaneously accept such a policy. Iran perceives all the matters from the angle of increased power inside and not outside of its national borders. In this respect, Iran’s regional presence is only limited to the time of insecurity and a reaction to the immediate sources of threats and instability (such as ISIS or the collapse of a friendly states in Iraq or Syria) to Iran’s national security. Some views believe that Iran’s connection with friendly local forces is a means to expand its regional influence. Yet one should also note the defensive nature of such policy.

The formation of local militant movements, such as the Hezbollah in Lebanon or Popular Mobilization Forces in Iraq, was primarily for tackling the foreign threats supported by Iran for both ideological and geopolitical reasons. No doubt that while these political forces achieved their capabilities in mobilizing the public, they have naturally tried to expand influence or integrate in their countries’ local politics, seeking their appropriate share of national and political power. This entails that their existence or continuation is not only for preserving Iran’s regional aims and principles. For instance in Iran’s domestic domain, the justification for Iran’s presence in Iraq, which is for battling the immediate threat of Daesh, is different from Iran’s battling in Syria, rejecting any logic of a long-term presence in the country.

In this regard, Iran has explicitly announced that it has no interest in establishing permanent military bases in Syria (11) for expanding its regional influence, opening up even a so-called “second front” against Israel, as recently discussed by some analysts or the Israeli regime. (12) Iran is well aware of the U.S. obsession to Israel’s security and wants no possible military engagement of the U.S. in Syria that could change the Syrian political scene in favor of the opposition forces. Meanwhile, the Iranian public is also sensitive about Iran’s prolonged presence in Syria as its costs affect Iranian daily economic life, acting at the expense of Iran’s development and growth. Of course, this does not mean that Iran will completely leave the region. Rather Iran is likely to shift its hard power presence to a soft one and in the realm of coalition-building with friendly political forces and elites in the national governments, prioritizing state-to-state relations, as it was the case in Lebanon and Iraq.

Previous pattern of Iran’s policy in Afghanistan and Iraq also shows that Iran never requested any military bases in these countries, as it was confident that it could preserve its influence through friendly local forces, who mutually feel that they need the Iranian factor to balance their status in their country’s domestic politics and regional relations. Iran’s outstanding role in defusing the Kurdistan Regional Government’s referendum bid for independence, which could lead to Iraq’s disintegration, is a clear example showing that Iran has a great deal of soft power levers of influence in the local politics.

Second, an inward-looking policy is more adoptable with the current realities of the “state” in Iran. Such policy has the theoretical bases of acceptance by different internal layers of power circles including the intellectual and public realm. Currently, there exists a meaningful discussion inside Iran that the country’s available economic resources are rather insufficient for covering a continued and vast regional presence which, as noted above, could delay Iran’s process of economic development. The discussion pivots around the idea that Iran is better off by reducing the costs of its regional presence after the removal of immediate threats to its national security, and focus on its soft power to create a secure and stabilized neighborhood, translating its current military success to diplomatic benefits, thereby institutionalizing its regional role and influence, taking advantage of its geopolitical centrality by conducting an interactive and accommodative policy.

Third, such a policy could balance the interests of regional and trans-regional actors, who may believe that Iran’s regional policy is likely to shift the traditional balance of power at the expense of other involved actors. For instance, Russia will support the participation of a strengthening and independent Iran in the regional politics. China, which seeks regional stability for the flow of energy for its increased economic growth, will support a strong Iran from within. European countries, due to their current geopolitical urgency of preempting the flood of refugees and growth of extremism and terrorism into to its borders, will support a stabilized region with Iran’s active economic and political participation. Turkey and India are also following this line of thinking towards Iran.

Conclusion

Iran’s foreign policy is seeking to balance and adjust itself between the two constants of “cooperation” and “deterrence” in the region. The emergence of ISIS and currently the formation of a regional coalition against Iran, coupled with Trump’s withdrawal from the nuclear deal, increased Iran’s sense of strategic insecurity and led the Iranian leaders to focus more on the deterrence aspect of the country’s foreign policy. This concept of deterring the threat has even demonstrated itself in the realm of Iran’s economic security. Iran has reacted severely to the Trump's policy of “cutting Iran’s oil exports to zero,” supported by Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, who announced that they would compensate the 2 million barrels loss of exports.

In his July 2018 European tour in Switzerland, Iran’s moderate president Hassan Rouhani stated that if Iran could not export its oil, (13) how other neighbouring countries could do so, referring directly to the country's traditional deterrence strategy over a calculated control of the energy flow in the Strait of Hormuz in the crisis time, (14) and its negative implications for the international energy security. Such reaction by the Iranian pragmatic president demonstrates the significance of the element of deterrence in the time of insecurity in Iran’s strategic calculus.

The main goal of the Iranian foreign policy conduct has been to produce national power through benefiting from its geopolitical advantages in the regional balance of power. With the U.S. withdrawal from the JCPOA and restoring the sanctions, the necessity of linking to the region’s political and economic dynamics and forming a regional connectivity to tackle the consequent geopolitical constraints will become more significant in Iran’s foreign policy conduct. Iran’s emerging “inward-looking” approach is more the result of such development.

Indisputably, a stabilized and strengthening Iran that feels more secure from the region will have more tendency to increased regional cooperation. The Nuclear Deal was concluded when Iran felt that it could institutionalize its regional status commensurate with its national power. Complete implementation of the principles of the JCPOA could increase Iran’s propensity for regional talks with the West and especially the United States. Instead and with the formation of an anti-Iran coalition, the sense of threats from the U.S. and its regional allies has increased in Iran’s strategic calculus, leading the country to enhance its means of deterrence in the region.

In all, Iran’s orientation towards regional cooperation or deterrence is dependent on the dynamics of regional developments and especially its relations with the United States. What is evident for now is that Iran, for deterrence matters, could not currently afford any absence in the regional balance of power, because it believes that lack of a strong regional presence will be easily filled by its regional rivals at the expense of the country’s security and economic interests. As the experiences of Lebanon, Iraq and Afghanistan crises show, Iran perceives an active presence in its neighborhood a necessity to produce sustainable security and national power. Yet in this process, Iran’s trend to a hard presence would shift to a soft presence and through strengthening relations with friendly political local forces to manage good neighborhood relations at the level of states.

(1) Admiral Ali Shamkhani, “Security of Syria is equivalent with security of Iran,” Iran Online, http://www.ion.ir/News/366810.html, June 2, 2018.

(2) Yara Bayoumy, Jonathan Landy and Warren Strobel, “Trump seeks to revive ‘Arab NATO’ to confront Iran, Reuters, July 27, 2018. See also: CJ Werlemen, “Trump’s “Arab NATO” idea is doomed to fail,” Middle East Eye, 8 August 2018.

(3) See Iran’s National 20-Year Vision at: http://irandataportal.syr.edu/20-year-national-vision

(4) Hessamaldin Ashena (Cultural Advisor of Iran’s president), “Stronger, more efficient governments in the region,” (in Persian), Journal of Strategic Studies of Public Policy, No. 20, Fall 2016, http://sspp.iranjournals.ir/article_23309_fe320f52e776e02c259b0379af687444.pdf

(6) Mohammad Javad Zarif, “Towards a new security model in the Middle East,” The New Arab, 20 March 2018, https://www.alaraby.co.uk/english/comment/2018/3/21/towards-a-new-security-model-in-the-middle-east

(8) 8 Ashena, “Stronger, more efficient governments in the region,” P. 222, http://sspp.iranjournals.ir/article_23309_fe320f52e776e02c259b0379af687444.pdf

(10) Mohammad Javad Zarif, “Iran’s foreign policy priority in the new government,” Mehr News, https://www.mehrnews.com/news/4053673/, August 10, 2017

(11) “Zarif says Iran has no military bases in Syria,” ISNA, February 19, 2018, https://en.isna.ir/news/96113017443/Zarif-says-Iran-has-no-military-bases-in-Syria

(12) Amos Yadlin and Ari Heistein, “Ending the War in Syria: An Israeli Perspective,” Council of Councils, September 21, 2017, https://www.cfr.org/councilofcouncils/global_memos/p39169

(13) Silke Koltrowitz, “Iran’s Rouhani hints at threat to neighbors’ exports if oil sales halted,” Reuters, July 3, 2018, https://af.reuters.com/article/commoditiesNews/idAFL8N1TZ1BE. This position was later on approved and reiterated by Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, “Iran leader back suggestion to block Gulf oil exports if own sales stopped,” Reuters, July 21, 2018, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-iran-nuclear-oil-khamenei/iran-leader-backs-suggestion-to-block-gulf-oil-exports-if-own-sales-stopped-idUSKBN1KB0EI

(14) Major General Mohammad Hossein Bagheri (Chief of General Staff of Iranian Armed Forces), “Enemy to pay heavy price if Iran’s oil exports from the Strait of Hormuz is Halted,” Mehr News, August 30, 2018, http://en.mehrnews.com/news/137270/Enemy-to-pay-heavy-price-if-Iran-s-oil-export-from-Strait-of