|

| [AL JAZEERA] |

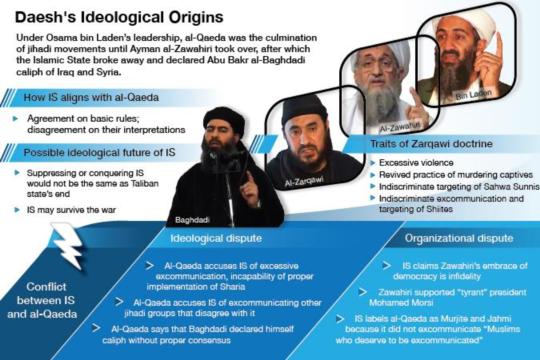

| Abstract Under Osama bin Laden’s leadership, al-Qaeda represented the culmination of jihadi movements hardened by experiences in Afghanistan. Al-Qaeda absorbed a broad spectrum of jihadi schools of thought that developed between the 1980s and Ayman al-Zawahiri’s ascension to leadership, followed by the Islamic State’s (IS or Daesh) breakaway and its declaration of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi as the caliph reigning over IS-captured territories in Iraq and Syria. Although IS concurs with al-Qaeda on basic principles, it disagrees with their interpretations. IS believes that Zawahiri deviated from al-Qaeda’s jihadi ways because he failed to denounce the Muslim Brotherhood’s leaders, especially after Mohamed Morsi was democratically elected as Egypt’s president. Daesh also holds Zawahiri responsible for Abu Mohammad al-Jolani’s breakaway from IS as al-Nusra Front in Syria. Al-Qaeda, on the other hand, accuses the Islamic State of extremism and ignorance regarding the application of the rules of jihad to groups and individuals, as well as of overzealous killing and denunciation. The future of the Islamic State organisation is tied to the fate of its self-proclaimed “state”, which, if it persists, would be a “caliphate” that’s internally extreme and externally flexible. If Daesh falls, it will become an extremist jihadi group to the right of al-Qaeda. Thus far, what is clear is that jihadi movements will individually engage in a new round of self-assessment, especially now that IS has declared a caliphate. |

Introduction

This report is based on the premise al-Qaeda and the Islamic State (IS) organisation’s ideologies sprung from the same roots. The theological roots of both originated from migrating jihadi movements encompassing a vast spectrum of groups and figures that are represented in al-Qaeda. Depending on the perspective from which it is viewed, Daesh is simply a breakaway protrusion of al-Qaeda as well as its natural progression. This might encapsulate the overall ideological framework of the organisation, but fails to clarify its peculiarities, especially since its actual conduct shows clear divergences from al-Qaeda. Using unique religious and jihadi slogans, the organisation succeeded in recruiting tens of thousands of volunteer fighters, a feat that al-Qaeda never even attempted.

To analyse the ideological roots that made the Islamic State organisation stand out, we must return to al-Qaeda’s origins, a group whose ideology made it stand out from among dozens of other jihadi groups during the so-called “Afghan jihad” period. This will enhance understanding of the conflict between al-Qaeda and Daesh, and interrogating the ideological differences between the two will also probe the strength of these ideas and their staying power.

There are three identifiable phases of jihadi movements: mobilisation for migratory jihad, global jihad and the Zawahiri era. It is important to note that these phases can overlap, and their distinguishing traits might intertwine, even ideologically, but they are most appropriate for this study as it traces Daesh’s ideological roots.

Afghanistan and mobilisation for ‘the duty of jihad’

Abdullah Azzam, founding father of “transnational Islamic jihad” and the foremost spiritual leader of so-called “migrant jihad”, wanted to “mobilise Muslims and Arabs to revive jihad in Afghanistan during the 1980s, with the ostensible aim being to liberate the country from Soviet occupation and turn it into a bastion for jihad, and thus a starting point for the liberation of Palestine, and to align other regimes, particularly Arab regimes, with God’s law and bring them under God’s rule”.(1)

Azzam’s call was in sync with the opponents of Soviet expansion in Afghanistan, led internationally by the US, and regionally by Pakistan and Saudi Arabia. Saudi citizen Osama bin Laden embodied the Wahhabi movement’s undertaking to “support Afghan Muslims”, despite the fact that there is still speculation whether or not bin Laden was actually supported Wahhabism at the time.(2) This aspect could help explain how the “Wahhabi doctrine” might have been altered to become a basic ingredient of jihadi thought.

Another aspect is the degree of criticism levelled against the Muslim Brotherhood’s doctrine, which was virtually the only doctrine that was complete enough to compete (politically and religiously) with that of the Wahhabis. Criticisms of the Brotherhood’s doctrine included lack of tenets’ clarity, as well as the Brotherhood’s “reluctance to use armed force”, seen as a “lack of its sincerity”. In other words, the concept of “jihad by change”, especially in Egypt and Syria, was criticised for having an ambiguous goal: seeking to “reform” incumbent regimes rather than the direct pursuit of a caliphate. This debate was heightened by the mobilisation of fighters in Afghanistan and particularly in Pakistan – fighters who originated from various ideological influences, from the Islamic far right to the centre. In those countries, the Wahhabi movement found both the freedom to demonstrate its thoughts and beliefs, and the time to get itself established.

This revived the debate about the experiences of Islamic groups that had engaged in struggles against their home countries’ governments, such as the Islamic Movement and Jihad Movement in Egypt, and the splinter groups which originated from them. In addition, the debate encompassed the Jamaat al-Muslimeen (Society of Muslims), which later changed its name to Takfir wal Hijra (Excommunication and Exodus), the jihad experience in Syria, and Mustafa abu Yaali’s Algerian experience, among various others.

Accompanied by a reconfiguration of Wahhabi thought within a political context outside of its Saudi confines, this debate was operationalised through a militant function in Afghanistan that it had not experienced since the establishment of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. In that context, there probably wasn’t a single idea about jihad, whether extreme or moderate, that wasn’t illuminated, each with its own proponents and opponents. Most of these ideas, though, never morphed into significant organisational frameworks, even though some of these ideas caused armed conflicts among Arab and Afghan mujahideen (fighters).

Global jihadi movement attributes were developed during this period of mobilisation for jihad in Afghanistan, which preceded the global phase. They include:

-

Jihadi mobilisation: Mobilisation, regardless of its various motives and purposes, remains the most prominent trait of that period. Everything that came after it, and enjoyed regional and international and, in some cases, official Arab support, was a continuation of Afghan jihad. It featured jihadi forums that included Arabs and non-Arabs, and issues that were previously obscure began to assume importance in the “Muslim psyche”, such as East Turkistan in China, Kashmir in India, Patani in Thailand, Moro in the Philippines, and so on. We can safely say that mobilisation peaked between Abdullah Azzam’s establishment of his “Services Office” in 1984 and his assassination in 1989.

-

Leadership of Jihadi thought: To facilitate and perpetuate mobilisation, it was necessary to devise a “jihadi manifesto” agreed upon by every jihadi leader in Afghanistan, regardless of creed, goals or priorities. Abdullah Azzam and the early advocates of jihad were keen to achieve that consensus. At this phase the idea of “jihadi scholars” in the field gained prominence. They actively supported jihad and saw themselves as scholars Muslims are obligated to listen to. It was a tactic to suppress opposing fatwas and opinions, and “adherence to jihad” became the sign of “honest leadership”. These ideas lent clout and immunity to jihadi thought, and gave it prominence within the Muslim world.

-

Accusations of “Murjiah and Jahmi”: These terms gained popularity and were used as an accusation against those who refused to excommunicate regimes that do not “rule according to God’s word” (or Shariah). Murjiah believe that faith is knowledge, and that any Muslim who expresses belief in God cannot not be rendered non-Muslim by sinning.

-

Using Sayyid Qutb’s writings as a reference: Qutb’s literature was considered as the comprehensive reference of all ideas brought forth during that period, despite the varied, and sometimes contradictory, interpretations of his line of thought. The reason for such consensus may be attributed to the absence of any prior literature of similar breadth, as well as the fact that he called for severing all ties with current regimes on a global level. It is clear, though, that the real imperative was to protect mobilisation from differences in opinion. Abdullah Azzam, whose ideological roots had been heavily influenced by the Muslim Brotherhood, was the driving force behind mobilisation, while his main partners in Afghan jihad at the time, namely the Wahhabis and the al-Jamaa al-Islamiyya in Egypt, were relentlessly critical of the Muslim Brotherhood. Though Qutb was technically a member of the Brotherhood, his line of thought was flexible enough to be interpreted in ways that would satisfy all sides, thus solidifying the consensus on the common goal of jihad, if only for a while.

Global jihad period

This can be divided into two phases: the period from Abdullah Azzam’s assassination to the declaration of al-Qaeda (1989 to 2001), and from the fall of the “caliphate” in Kabul to the killing of Osama bin Laden on 2 May 2011.

Phase one: 1989 to 2001

Politically, the countries that had facilitated the convergence of mujahideen began to adopt the opposite policy - to facilitate their departure (especially after 1992),(3) either sending them back to the countries they came from or to other countries that would accommodate them after facilitating their travel to Afghanistan. Once the Soviets had withdrawn from Afghanistan in 1989, and the pro-Soviet regime had fallen in 1992, there were increasing complaints about the disruptive aftermath of “Afghan jihad” in various countries. At the time, jihadi movements had begun to globalise and move on to other flashpoints in a much more organised fashion: to Algeria, where the “Bleak Decade” (the Algerian civil war) had just begun; to Chechnya, where the war had intensified between 1994 and 1996; and to Bosnia and Herzegovina between 1992 and 1995. During this period al-Jamaa al-Islamiyya also conducted a slew of attacks inside Egypt until 1997, when it announced a nonviolence initiative, which was followed by various repudiations.

In terms of leadership, Osama bin Laden was consolidated as the actual successor of Abdullah Azzam, though he took a while to announce his position on his relationship with Saudi Arabia, to which he never returned. Instead, he went to live in Sudan between 1992 and 1996, the same period that al-Jamaa al-Islamiyya was active in Egypt, leading to accusations that he had some hand in the group. Sudan, however, repeatedly denied this, claiming that bin Laden was there as a business investor, not a “mujahid”. He was pursued by the US, and his Saudi citizenship was revoked in 1994,(4) which forced him to go back to Afghanistan as a “mujahid”, where he culminated his efforts in allying with Mullah Omar, the Taliban’s emir. That alliance gave al-Qaeda the image and nature for which it became popularly known, and was consolidated when the organisation announced its front to fight “crusaders and Zionists” in the summer of 1998.

Throughout that period, Afghanistan never stopped playing host to jihad and was a ready and willing haven for everyone who returned there seeking refuge or otherwise, with the porous Afghan-Pakistani border making access to the country especially easy. Jihadi groups continued to accommodate Arabs, despite the transient small wars that periodically erupted among them after the Northern Alliance, led by Burhanuddin Rabbani, overtook Kabul. In fact, the Arabs themselves sometimes split up – the most prominent example of which was the split between Rabbani’s and Gulbuddin Hekmatyar’s groups. After the Taliban took control of Kabul in 1996, the city became a hotbed for migrant global jihad.

The most important traits of this organisational phase of migrant jihadi movements follow below:

-

Al-Qaeda became the ideological regulator to which all Afghan jihadi groups deferred, despite their many differences. It was able to contain and supercede the ideological recantations of Egypt’s al-Jamaa al-Islamiyya throughout the 1990s.(5) Al-Qaeda learned a significant lesson from the failed jihadi experience in Algeria.(6) At the time, Kabul became the established centre for planning and guidance of jihad, despite its effectiveness in that role.

-

Al-Qaeda launched its version of jihad as a middle ground between the Muslim Brotherhood (labelled a reform movement rather than one for comprehensive change), and various other Islamic groups which had significant presence on the Afghan scene but advocated ideas that were extreme even by al-Qaeda’s standards. Also, al-Qaeda sold itself as a “halfway” organisational solution, one that rejected the “political party” model based on “fanaticism”, while simultaneously not acknowledging anyone who claimed the caliphate without meeting an established set of conditions.(7)

-

At that time al-Qaeda was the epitome of organisational and ideological development of migrant jihadi groups, and it could not go beyond the concept of “leading by ideals”. Even though the fabric of those groups was highly organic in Afghanistan, and in some cases, leadership was remotely exercised through delegates or messages sent out to jihadi flashpoints in other countries, the model of leadership remained based on “allegiance” to jihad. Leadership was based on ideals, and guidance was through the spoken word, which was probably meant to avoid “party fanaticism”(8) in an attempt to hold the jihad movement together.

-

Organisationally, al-Qaeda sold itself on the premise of fighting a remote enemy, namely the US and Zionists, with the option of fighting its more immediate enemies, regimes in several Arab and Islamic countries, based on its analysis of the confrontations with those regimes. Al-Qaeda became convinced that those regimes drew their power from the US and the Zionists. Al-Qaeda also feared that, if it expressly declared war against these regimes, the military confrontation would involve the actual peoples of these countries, deemed to be suppressed by tyranny and ignorance. However, al-Qaeda never openly encouraged the idea that the US and Israel should be fought on their own turf, which effectively meant that it never neutralised Arab and Muslim territories. By targeting foreign interests in those territories, it was again drawn into direct confrontation with those regimes. Significantly, the notion of “confronting the remote enemy” which was part of al-Qaeda’s dogma at the leadership level, was never clearly established at the grassroots ideological level, and never became a discernible course of action throughout the organisation, whose closer mental goal was “to establish an Islamic State”.(9,10)

During this period, internal discourse became more detailed, enabled by the advent of new communication media, and the increase of jihadi volunteers with accumulated experience, expertise and scholarly work. But for many fundamental issues, which remain up for debate today, al-Qaeda never managed to establish widely-accepted guidelines, particularly given that those issues are open to interpretation. They include infidelity (takfir) in deed and in person, pardoning violators and emirship and emirs in contemporary times.

-

Infidelity in deed and in person: In this issue, aspects of jurisprudence and faith are greatly tangled. In short, the infidelity of the deed does not necessarily stipulate the infidelity of the actor, unless certain conditions are met and others are absent. There are detailed rules in jurisprudence books that can be referred to on a case-by-case basis. Even though al-Qaeda had clearly stated that certain regimes and their figureheads were blasphemous, there were other issues that required the judgment of a higher intellectual authority. These included al-Qaeda’s position on Islamic political parties that chose democracy to bring about change and “recapture the rule of Islam” (e.g. Muslim Brotherhood); its position on members of a given regime’s security forces and on those who identify with non-Islamic movements or secular movements; its position on people who do not fully align with al-Qaeda, and the circumstances under which those people could be labelled as infidels and targeted for elimination.(11)

-

Pardoning the violator: This is based on the excommunication of the person who violates the set laws. Since excommunication of an opponent without giving them the benefit of the doubt could case rifts within the Muslim community in general and the jihadi community in particular, the presence of an excuse is a preventative way of attributing infidelity to individuals and groups. Three parameters were identified for this path: ignorance, interpretation and error – in other words, the lack of intent towards infidelity itself. On another level, the debate centred on whether excuses should be taken into account in issues of faith. What the jihadi movements could not yet clearly agree upon, though, was the boundary between what is and what is not an issue of faith, who has the authority to decide the validity of an excuse and what checks and balances should be incorporated to guard against personal vendettas.(12)

-

Emirship and the emir: this issue surfaced as a result of the advent of migrant jihad, with the purpose of addressing two issues that threatened to cause jihad to grind to a halt, or, more specifically to overcome two obstacles:

-

The lack of a Shariah ruler who would have the authority to declare jihad in the first place and jihad under his rule in the second, i.e. to achieve the legitimacy of jihad and jihad’s leadership. This had emerged in the early stages of mobilisation, even though some of related issues have remained undecided, and are being discussed continually.(13)

-

The prohibition of “partisanship”, something rejected by the jihadi movement probably out of its own intellectual devices, or from Salafi or Wahhabi influence by movements that had sponsored Afghan jihad. They considered “partisanship” as a characteristic of jahiliyyah (the ignorance or pre-Islamic ages). Hence, a consensus was born that since those groups were brought together for the purpose of Jihad, the presence of an organisation is henceforth a prerequisite of jihad, and therefore the legitimacy of the emir is tied to jihad, as is the entire political work of the organisation. All of this was to give credibility and purpose to jihadi movements. However, many sub-issues pertaining to this issue, such as the multiplicity of fighting venues and their emirs, and the connections between them, remain unresolved.

-

These three issues are always prone to breed dissent among jihadi groups and leaders. They carry varied weight and importance from one group to another, and extreme interpretations have caused some jihadis to go overboard in labelling their opponents as infidels, and have linked the legitimacy of a specific leader to his declaration of jihad in particular, i.e. the presence of a war to be fought in addition to the presence of a warlord or a caliph.

Phase two: from the fall of Kabul to the bin Laden’s assassination

Between the fall of Kabul in 2001 and the assassination of Osama bin Laden on 2 May 2011 came the 2003 fall of Baghdad, which created yet another battleground on which to fight Washington. That battleground was shared among various national Iraqi and Islamic militias before it ended with US withdrawal from Iraq in 2011.

A key trait of this period was the multitude of battlegrounds: Yemen, the GCC states, Iraq, and the Islamic Maghreb. Another was the increased militarisation of conflict, with hostilities not confined to al-Qaeda’s traditional modes of attack. Al-Qaeda’s branches began to take control of territories and handle security within them, or at least move freely, such as in the Maghreb and Iraq. During this period, al-Qaeda lost Kabul as a central reference point, where experiences, opinions and derivations (independent interpretations of the Quran and Hadith) converged. Fragmentation in the adoption of ideas and derivations by whoever controlled the situation on the ground became the norm, and although these groups still labelled themselves as jihadis or allies of al-Qaeda, this was largely more symbolic than literal.

A key change that affected some branches of al-Qaeda in terms of their ideological thought during this period was the conversion of “close-by” and “remote” enemies. The US evolved into a “close-by” enemy, both because of the geographic proximity brought about by its occupation of Iraq, and because of its increasing and more frequent alliances with other nearby enemies, namely Iran and Arab and GCC regimes. This alliance among enemies prompted the formation of “awakening” forces within Sunni communities and sectarian militias in Shia communities. As a result, the idea that “fighting apostates takes priority over fighting original infidels” began to take hold, as did the idea of the infidelity of “Rafidah” who conspired with occupying forces, hardening attitudes towards the Shias and “sectarian rule” in Baghdad.

It is certain that the most important element in al-Qaeda’s evolution at this stage was new, pivotal fronts for jihad, far away from the organisation’s leadership, which was experiencing difficulties and at times had little influence on remote battlegrounds. This is when Abu Musab al-Zarqawi (formerly Ahmed al-Khalayleh) became al-Qaeda’s rising star in Iraq. His approach in thought and action differed from that which al-Qaeda was used to, and this generated mutual criticism between himself and his mentor Abu Muhammad al-Maqdisi (formerly Isam al-Barqawi).(14)

Zarqawi, who was said to epitomise the “next generation” of jihadis, was killed in June 2006, bequeathing a peculiar legacy that left its mark on jihadism in Iraq. This seems to have grown more intense and took root after the killing of bin Laden and Zawahiri’s subsequent leadership of al-Qaeda. Zarqawi’s methods were distinguished by excessive violence, which, by al-Qaeda’s standards, was akin to the Algerian model seen by the organisation as fraught with deviations. This in turn cost Zarqawi his “legitimacy” as a jihadi. Combined with antagonising his host population, this ultimately caused him to fail. Zarqawi was more of an anomaly within al-Qaeda than a natural progression for the following reasons:

-

He overplayed the so-called “Sunnah” (prophetic way) of slaughtering captives and prisoners, and disseminated this through the media to spread fear. It can be said that he was the person who popularised this brutal practice among jihadi movements.

-

He went to extremes in targeting members of the Sunni awakening movements and anyone who was part of the new Iraqi regime in any way, shape or form. He also fanned the flames of conflict among other jihadi groups with whom he fought against the Americans and the Iraqi government.

-

He opined that the Shias must be excommunicated en masse, and indiscriminately targeted their populations in Iraq because of their alliance with the US and their pursuit of Iraqi insurgents, many of whom were Iraqi and migrant mujahideen.

-

He drew criticism from al-Qaeda’s leadership for his indiscriminate excommunication of the Shias at large, random targeting of civilian and combatant Shias, and his excessive targeting of Sunnis, in addition to the little wars he started with other jihadi groups left and right instead of directing aggressive efforts towards the occupiers.

A lot has been said about Zarqawi, his disobedience to al-Qaeda, and the criticisms he encountered from the organisation and some of its spiritual leaders. Bin Laden’s presence bonded the organisation together, protecting it from splintering, because of his symbolic power, a major factor behind the sustained mobilisation and the constant supply of volunteers who continued to join al-Qaeda for years. This, however, did not prevent some of its branches and local leaders from disobeying his directives or interpreting them according to their own situations, given his geographical remoteness and also because his presence and ability to communicate were weakened due to security concerns. After his assassination, al-Qaeda seemed to have lost a significant amount of its immunity, impact and cohesion.

Zawahiri’s leadership and the Arab revolutions

Because of the differences in character between the two men, many opined that the al-Qaeda which Zawahiri inherited wouldn’t be the same entity that bin Laden had established, whether in terms of cohesion, thought or action. In addition to his charisma, the relatively young bin Laden had the distinction of being the founder of the “jihadi movement”. He was seen as a leader and role model with a vast network of relationships and resources. While Zawahiri did have spiritual power, especially at the organisational level, his lack of charisma after he took over prevented him from filling the void left following bin Laden’s death, and he was unable to impose his own organisational, intellectual and political preferences during this new era.(15)

Zawahiri inherited an anomaly in Iraq and a budding, burgeoning jihadi scene in Syria. He had to deal with a rapid chain of events in other Arab Spring countries, including ones that had an al-Qaeda presence, albeit large or small. He also had to handle the organisation’s need for reorientation and to restore control over it, especially at a time when there were rumours that bin Laden had been about to review and reorient al-Qa’ida’s progress (16,17) but was killed before he could embark on that project.

Zawahiri also inherited a copious legacy of jihad. Al-Qaeda was no longer an organisation led by young scholars, often called “Shariah students”, who issued fatwas to mujahideen with little or no experience in juridprudence. Now it had real spiritual leaders like Abu Qatada al-Filistini (formerly Omar Mahmoud Othman), Maqdisi, and several others who now strive to defend al-Qaeda’s legitimacy.

The Arab revolts were Zarqawi’s biggest challenge. Because of their sheer abruptness and unpredictability at a time when al-Qaeda was expanding, they presented a model of change through peaceful protest without necessarily resorting to armed conflict (except for Syria, due to its unique circumstances), and they gave the Brotherhood model of political change such a strong new impetus that even Salafi groups jumped onto the bandwagon, dropping their former reservations about what is or isn’t allowed in their approach to politics. That new momentum also caused them to drop many of the calls for excommunication pertaining to the democratic process, the exchange of power and many other mechanisms of democracy. The change in Egypt was so overwhelming that the unthinkable happened: a Brotherhood leader, Mohamed Morsi, was elected president, gliding into office on the back of a broad Islamist alliance that included Brotherhood members, Salafis and others, not to mention their subsequent permeation within government and parliament. This preceded the period when Arab revolts began to wane, such as the coup in Egypt and most other Arab spring countries sliding into civil war and chaos, with the exception of Tunisia.

Al-Qaeda, among others, was definitely taken by surprise at the rapid success of national revolutions that toppled entire regimes – so much so that it took its time in putting forth an opinion about these events. It lost its founder and spiritual leader at a time when it was still trying to figure out answers for the questions the initial success of the revolutions had posed. When al-Qaeda did come up with its own answers, it framed these revolutions within its own ideological frameworks, as evidenced in the statement that announced Zawahiri as bin Laden’s successor. As a step towards comprehensive change, al-Qaeda announced its support for the revolutions in principle: “[Al-Qaeda supports] the uprising of our repressed Muslim people in the face of tyrants… [We] urge them and other Muslim nations to rise up and continue to fight… until real change has come in the form of Shariah rule”.

Al-Qaeda went even closer to the Islamic revolution’s discourse in Iran and the global left. “Change shall not come about unless the nation does away with every form of occupation, domination, and military and economic submission”, read the statement. Al-Qaeda also declared its “sympathy for the suffering of the oppressed”, and that its jihad against “American arrogance shall alleviate the injustice they suffer”. All through Zawahiri’s public statements, there is the sense that he was worried about the US taking control of the revolutions, especially the one in Egypt, and that Washington was seeking a replacement for Mubarak who was no longer useful. He also warned of the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces and its potential coup. After that actually happened, a clear position of support for Morsi can be detected in al-Qaeda’s discourse, albeit with the condition that showing unprecedented sympathy for the Brotherhood did not mean they did not have reservations about their methods.(18,19)

Conflict between the Islamic State and al-Qa’ida

The key factor that triggered the dispute between al-Qaeda and the Daesh was Zawahiri’s position on the disagreement between Abu Muhammad al-Jolani (real name unknown) and Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi (formerly Ibrahim Awwad al-Badri). Zawahiri had approved Jolani as emir of al-Nusra Front in Syria, confined the IS’ authority to Iraq, and assigned Abu Khalid al-Suri (formerly Muhammed al-Bahaiya), a long-time companion of his and bin Laden’s, to mediate between the two. Daesh rejected Bahaiya’s appointment. He was eventually killed in a suicide attack that al-Qaeda accused the Islamic State of carrying out, triggering a war between the two entities in Syria.(20,21,22)

Since then, the two sides have engaged in a propaganda war: al-Qaeda accused the Islamic State of being “Kharijites” and “the descendants of Ibn Muljam”. IS countered that al-Qaeda had deviated from “the rightful path” which they believed they were still on. IS went further by declaring Baghdadi caliph, and therefore a reference point not only for jihadi movements, but for all Muslims, in an apparent one-upmanship attempt against al-Qaeda and Zawahiri. Under the premise that the “caliphate” is supreme to the “emir of fighting”, this would effectively strip al-Qaeda (and Zawahiri) of legitimacy, and by so doing, would make Mosul and its new ruler the centre of jihadi culture, vision and action.

There are several key positions that can be deduced from the ideological clash between the two factions.

From al-Qaeda’s perspective:

-

Al-Qaeda accuses Daesh of taking excommunication to the extreme and of incompetence in the proper application of Shariah law. Al-Qaeda alleges that the “Shariah scholars” who assumed positions of ideological leadership are “too young to declare infidelity of deed on others”, whether as applied to Sunni Muslims or other Muslims.

-

Al-Qaeda contends that Baghdadi declared himself caliph without the global consensus of Muslims and that he sufficed with the allegiance of only a few of his followers in Iraq without consulting with the Muslim population at large, and that Baghdadi, among other prerequisites that Shariah says he does not have, is a previously unknown figure to Muslims at large. Al-Qaeda says that every allegiance given to him – especially by certain jihadi groups – is therefore null and void.(25)

From Daesh’s perspective:

-

Zawahiri’s effective endorsement of democracy is a clear infidelity, given his endorsement of Arab revolts and their methods of “peaceful change”, the same method the Muslim Brotherhood had adopted, and the very one that al-Qaeda had diverged from in an attempt to become a more aggressive alternative to the Brotherhood.

-

IS severely criticised Zawahiri for his “endorsement of the tyrant”, a reference to former Egyptian president Mohamed Morsi, who (after having been imprisoned) embraced democracy. They point to Zawahiri’s failure to excommunicate him, and Zawahari’s public thanks to Morsi when the latter announced he would work towards rescuing Omar Abdul Rahman from incarceration in the US. The Islamic State says that al-Qaeda’s creed is to “excommunicate anyone who defers to tyranny” (i.e. democracy), and that the Zawahiri-led Al-Qaeda has failed to excommunicate the Brotherhood’s senior leaders, who, according to Abu Muhammad al-Adnani ( formerly Taha Subhi Falaha), the Islamic State’s spokesman, are “worse than secularists”.(26)

-

It labelled Al-Qaeda as a Murji and Jahmi group because the latter would not excommunicate Muslims who, according to the IS, commit sins that would render them non-Muslim. This was in response to Al-Qaeda’s second contention in the previous section.

-

The IS labelled al-Qaeda as “Sarurist”, a derogatory epithet meaning that al-Qaeda aligned itself with the movement of Muhammed Suroor Zain al-Abideen, whose ideology combined political work with the perceived legitimacy of the Muslim Brotherhood, as well as Sarurism’s attitude in dealing with opponents and Salafis. With that slur, IS infers that al-Qaeda is increasingly becoming more involved with politics and pacifism than with jihad.

The point is that the IS adopts the same guiding principles as al-Qaeda, but differs with the latter on some interpretations that might be popular with al-Qaeda but less so with IS. The biggest cause of conflict between the two, barring personal and organisational differences, is their different understandings of Shariah rules and their implementation. Surely this can only foment greater conflict in the future. A person who called himself Abu al-Qasem al-Wahshi al-Asbahi said as much in an open letter he titled “Certainty is A Characteristic of the Confident”, in which he replied to an open letter by Abu Muhammad al-Maqdisi, titled “Equity is the Characteristic of the Honourable, and the Honourable are Few”, in which the latter criticised those who took excommunication to extremes, writing, “We do not denounce [Maqdisi’s] interpretation, but denounce [his] implementation”.(27)

Daesh chose the most extreme interpretation in its implementation of the same rules that al-Qaeda had previously used to destroy the legitimacy of rival Islamic movements and to solidify the Shariah (Islamic law) roots of its push for jihad. With its declaration of the caliphate, IS is hoping to add legitimacy to its excesses in the interpretations of Shariah rules and its denouncements of al-Qaeda’s spiritual leaders, based on the premise that these interpretations are approved by the caliph himself and aren’t just scholarly opinions. It also wants to revive long-obsolete practices like enslavement and spoils-gathering, as well as the implementation of Islamic criminal law punishments (hudud) and the like. IS hopes to make its so-called “state” a chosen destination for jihadis who would come to support it in its methodology and the wars that it wages. In other words, the region is up against an attempt to establish a new base for even more vicious, brutal jihad.

The Islamic State’s ideological future

The future of the ideology that Daesh wants to establish depends on how deeply entrenched it will become, and how long the organisation can withstand the global war being waged against it. There are two possibilities here, the most likely of which is that the organisation will be suppressed or defeated, ultimately meeting the same fate as the Taliban state. Ideologically, it could turn into a splinter jihadi group to the right of al-Qaeda, inevitably engaging in a conflict with the latter, which has the clout, global support, historical legitimacy and consistent discourse that IS does not.

Based on this scenario, however, the ideologies of jihadi movements in general, and that of the IS in particular, will inevitably be subjected to thorough reviews, similar to what happened within the jihadi movements in Egypt, Libya, and other areas. Daesh has taken the ideas brought forth by jihadi movements, particularly Al-Qaeda, to full saturation, at a time when Arab nations were moving away from that trend.

More specifically, Daesh is the exact opposite of the Arab revolts’ products, which, by the Islamic State’s standards, reached the height of “Murji-Jahmi thought” by allowing the Muslim Brotherhood to take power democratically. The Islamic State’s rivalry with Al-Qaeda notwithstanding, it also appears to be in rivalry with the products of Arab revolts: its response to the “peaceful change” desired by these revolutions was “change through jihad”. It therefore unleashed its full brutality, employing a much crueller, coercive and ferocious version of jihad. With extreme ruthlessness and tyranny, it hastily set out to establish a state, as if to avert any errors that would have allowed a “successful democratic model” to put an end to jihadi movements and force them to undertake a critical inward review.

But the organisation cannot escape that fate – it has already arrived, embodied in the war raging between Al-Qaeda and IS: rather than fighting their proclaimed enemies, jihadis are fighting each other. They are fighting over everything: the caliphate’s declared legitimacy, the legality of the punishments being exacted on whosoever happens to be present and the random, indiscriminate bloodshed. They are calling each other every pejorative name they can fish out of history books and their own transformations: Murjiah, Kharijites, apostates, etc. What cannot be ruled out is the possible emergence of new movements that combine the jihadi legacy of al-Qaeda with the political legacy of conservative movements as well as the Muslim Brotherhood to fight injustice, tyranny and occupation, especially since there are still battles to be fought on Arabian soil.

The other, more remote possibility is that Daesh survives this current war, and the caliphate state it declared survives, if only in a small spot in the region, either as part of a new order or as a result of regional and international balances of power. If that happens, that state would be home to a more radical Salafi model, but might also be able to cope with, and worm its way in as part of the global system. It might even serve as a stabiliser to Iran, especially ideologically. Under that latter scenario, the reality of politics would have refined it and sufficiently filed down its rough edges to make it relatively less radical.

_______________________________________

Shafeeq Choucair is a researcher at AlJazeera Centre for Studies specialising in the Arab world and Islamic movements. He covered events in Afghanistan between 1992 - 1998 as well as the Iraq war after the fall of Baghdad in 2004.

Endnotes

1. Abdallah Kamal, “Black Banners” series, Asharq Alawsat, May 2002. Accessible here: http://classic.aawsat.com/details.asp?issueno=8555&article=100961 http://classic.aawsat.com/details.asp?issueno=8556&article=101142 http://classic.aawsat.com/details.asp?issueno=8558&article=101495 http://classic.aawsat.com/details.asp?issueno=8559&article=101638 http://classic.aawsat.com/details.asp?issueno=8560&article=101807.

2. Bashir Nafi, “Islamists”, In: Cross-Continent Violence, (Beirut: AlJazeera Centre for Studies and Arab Scientific Publications, 2010), 205.

3. Mohammed Shafii, quoting Hamed Mustafa Abu al-Walid al-Masri, “Chat on the Roof of the World Series’, Asharq Alawsat, October 2006, http://classic.aawsat.com/files.asp?fileid=25.

4. Hamed Mustafa’s website can be found here:http://www.mustafahamed.com/.

5. Interview with Prince Turki Bin Faisal, former director of the Saudi General Intelligence Agency, and what he said about Osama bin Laden, 8 November 2001, http://classic.aawsat.com/details.asp?article=65453&issueno=8381.

6. Assakina website, “Analysis of the Recantations of Jihadi Groups”, 8 February 2012, http://www.assakina.com/centre/files/12767.html.

7. Aafaq website, “Syrian Member of Afghan Arabs Tells of His Experience with Algerian Terrorists”, 13 April 2008, http://www.aafaq.org/news.aspx?id_news=5003. Note that the Syrian is Abu Musab al-Suri, who published a text titled “Brief Testimony of Jihad in Algeria”, which can be found at this forum link: http://benbadis.org/vb/showthread.php?t=12270.

8. Muhammed Shafii, quoting Hamed Mustafa Abu Al-Walid Al-Masri, “Chat on the Roof of the World Series”, Asharq Alawsat, 25 October 2006, http://classic.aawsat.com/details.asp?issueno=10193&article=388935.

9. Assakina, “Partisanship is the Problem So Understand It”, 27 May 2011, http://www.assakina.com/taseel/8056.html.

10. Murad al-Shishani, Al-Qaeda: Geopolitical and Strategic Vision and Social Structure, Emirates Centre for Studies and Strategic Research, 25.

11. Fouad Hussein, Al-Zarqawi: The Second Generation of Al Qaeda, (Dar Elkhayal, 2005), 44-45.

12. There are many books on the subject, but to get a better understanding of Al-Qaeda’s thoughts, watch the video by Abu Qutada titled “Definitive Answer on Monotheism”, uploaded 3 December 2012, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YQFKs81s4os.

13. Abu Muhammad al-Maqdisi, “Doubt: Excusing Tyrants for Ignorance and Imposition”, Tawhed and Jihad website, http://www.tawhed.ws/r?i=rv8duxmp. Maqdisi is the author of the famous book Millat Ibrahim (The Faith of Abraham), a major reference for jihadi movements, including the Islamic State itself. Daesh actually confronts Maqdisi with this very book to justify its excommunication of opposing groups like the Muslim Brotherhood. The book, undated, is available here: http://www.tawhed.ws/r?i=iti4u3zp.

14. The position of jihadis on leadership is still close to that of Sayyed Imam al-Sharif, which he illuminated in chapter three of his book, Al-Omdah Fi Edad al-Uddah (Guide to Preparing for War), which is that the presence of leadership is a prerequisite for jihad, even in the absence of a caliph.

15. See transcript of AlJazeera interview with Maqdisi:

http://www.aljazeera.net/programs/today-interview/2005/7/10/%d8%a3%d8%a8%d9%88-%d9%85%d8%ad%d9%85%d8%af-%d8%a7%d9%84%d9%85%d9%82%d8%af%d8%b3%d9%8a-%d8%a7%d9%84%d8%b3%d9%84%d9%81%d9%8a%d8%a9-%d8%a7%d9%84%d8%ac%d9%87%d8%a7%d8%af%d9%8a%d8%a9. A video of the interview can be seen here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z3QBKvkLv-o. See Zarqawi’s response to Maqdisi on the blog titled Immigration to Monotheism: http://ak-ma.blogspot.com/2013/03/blog-post_9.html.

16. Aljarida website, translation of a study by the Combating Terrorism Center at West Point, published in a series starting16 January 2008:

http://www.aljarida.com/news/index/216897/

http://www.aljarida.com/news/index/217241/

http://www.aljarida.com/news/index/217576/

http://www.aljarida.com/news/index/217833/

http://www.aljarida.com/news/index/218104/.

17. Don Rassler, Gabriel Koehler-Derrick, Liam Collins, Muhammad al-Obaidi, and Nelly Laho, Letters from Abbottabad: bin Laden Sidelined? Combating Terrorism Center, West Point, 3 May 2012: https://www.ctc.usma.edu/posts/letters-from-abbottabad-bin-ladin-sidelined.

18. Yasser Zaatreh, Bin Laden’s Image in Letters from Abbottabad, 2012,

http://www.aljazeera.net/knowledgegate/opinions/2012/5/10/صورة-بن-لادن-في-وثائق-إبت-آباد.

19. Mohammed Aburumman, Al-Qaeida’s Ideology and Coping with Arab Revolts, July 2011,

http://digital.ahram.org.eg/articles.aspx?Serial=643521&eid=6738.

20. Mohammed al-Shanqiti, Bin Laden’s Legacy in the Age of Revolts, 4 May 2011, http://www.aljazeera.net/knowledgegate/opinions/2011/5/4/%D8%AA%D8%B1%D8%A7%D8%AB-%D8%A8%D9%86-%D9%84%D8%A7%D8%AF%D9%86-%D9%81%D9%8A-%D8%B2%D9%85%D9%86-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AB%D9%88%D8%B1%D8%A7%D8%AA.

21. Alhayat, “The Death of al-Qa’ida Mediator Abu Khaled Al-Suri”, Alhayat, 13 November 2014, http://www.alhayat.com/Articles/752220/-%D9%88%D8%B3%D9%8A%D8%B7-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%82%D8%A7%D8%B9%D8%AF%D8%A9--%D9%82%D9%8F%D8%AA%D9%84-%D8%A8%D8%B1%D8%B5%D8%A7%D8%B5%D8%A9-%D9%81%D9%8A-%D8%B5%D8%AF%D8%B1%D9%87-%D9%82%D8%A8%D9%84-%D8%A3%D9%86-%D9%8A%D9%81%D8%AC%D9%91%D8%B1--%D8%A7%D9%86%D8%AA%D8%AD%D8%A7%D8%B1%D9%8A%D8%A7%D9%86--%D8%AD%D8%B2%D8%A7%D9%85%D9%8A%D9%86-%D9%86%D8%A7%D8%B3%D9%81%D9%8A%D9%86-%D8%A8%D9%85%D9%82%D8%B1--%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A3%D8%AD%D8%B1%D8%A7%D8%B1-.

22. Walid Ghanem, “Who is Abu Khaled Al-Suri?”, All4Syria, 24 February 2014,

http://www.all4syria.info/Archive/132991/.

23. Mohammad Aburumman, “A Reading in the Conflict between Zawahiri and Baghdadi”, Aljazeera, 22 May 2014,

http://www.aljazeera.net/knowledgegate/opinions/2014/5/22/%D9%82%D8%B1%D8%A7%D8%A1%D8%A9-%D9%81%D9%8A-%D8%A3%D8%A8%D8%B9%D8%A7%D8%AF-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AE%D9%84%D8%A7%D9%81-%D8%A8%D9%8A%D9%86-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B8%D9%88%D8%A7%D9%87%D8%B1%D9%8A-%D9%88%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A8%D8%BA%D8%AF%D8%A7%D8%AF%D9%8A.

24. Abu Mariya al-Qahtani, Glaring Proof of the Ignorance of Radicals, 2014.

25. Abu Mohammed al-Adnani, “Excuse Me, Al-Qaeda Emir”, audio clip, uploaded 11 May 2014, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6Ri71R9QeFA, and Al-Qaeda’s video response, titled “Silencing Issue: Rejection of Adnani’s Fabrications against Sheikh Zawahiri”, uploaded 2 June 2014, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=70D1Ezko7rw.

26. See the organisation’s position on the Arab Spring, the Muslim Brotherhood, and appeasement in this video, uploaded 31 January 2013, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9N2yVA8zdfc. A full transcript can be found here:http://www.muslm.org/vb/showthread.php?518885-%D8%AA%D9%81%D8%B1%D9%8A%….

27. The Arabic text of al-Asbahi’s letter can be found here: http://thabat111.wordpress.com/2013/11/09/%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AA%D9%91%D9%8E%D8%A8%D9%8E%D9%8A%D9%91%D9%8F%D9%86%D9%8F-%D8%AD%D9%8F%D9%84%D9%91%D9%8E%D8%A9%D9%8F-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%85%D9%8F%D8%AA%D9%8E%D9%8A%D9%8E%D9%82%D9%91%D9%90%D9%86-%D9%81/, and the Arabic text of al-Maqdisi’s open letter can be found here: http://azelin.files.wordpress.com/2013/10/shaykh-abc5ab-mue1b8a5ammad-al-maqdisc4ab-22justice-is-the-character-of-the-honorable-and-the-honorable-are-the-less-available-variety22.pdf.

| Back To Main Page |