|

| [AL JAZEERA] |

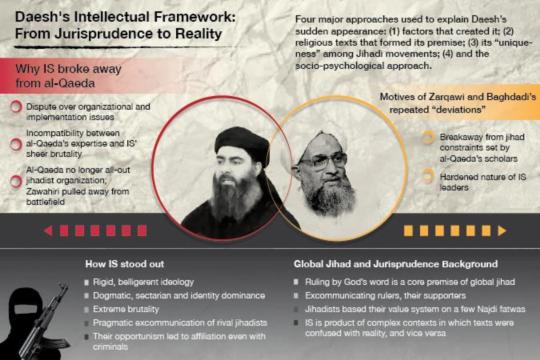

| Abstract This report explores approaches that have been used to explain the phenomenon of the so-called “Islamic State” (IS or Daesh), and will focus on four of them: context and factors of its formation; the religious and jurisprudential texts on which it is premised; social and psychological factors; and fourthly, the proposition that the Islamic State is an anomaly in the history of global jihad. The author suggests a two-pronged approach: first, discarding the idea that the organisation’s exceptionality sets it apart from the global jihad movement, and second, breaking away from considering it a “label” that can simply be attached to a certain line of thought or group. This is embodied in the analysis of the ideological structure of the organisation (its roots, developments, origins and products) on the one hand, and in an analysis of the complex circumstances in which this ideology appeared, on the other. To do this, the author reviews original texts of the spiritual leaders of global jihad and chronicles the development of events and their effects on organisational relationships, taking into account the global context on the one hand and the context of other Islamic movements on the other. The report comes to the conclusion that Daesh is the product of complex contexts in which religious texts and reality intertwine, and that it is a progression of global jihad rather than an aberration of it. |

Introduction

The many and varied approaches that have sought to explain the Islamic State (IS) can be grouped into four main streams. The first approach tackles the context and factors that led to its formation, and the instruments than can help understand and explain it. The context here includes several aspects. Socially, there are issues like runaway demographic growth, unemployment, and poor education, to name a few. Politically, there is the reality of severe tyranny (especially in the very lands IS or Daesh happens to control, Iraq and Syria), the failures of regional nation-states in the areas of development, citizenship, and managing relationships among various ethnicities. Historically, these factors have resulted in massacres, imprisonment, torture and civil wars.

This complex context attributes IS’ emergence to the decades-long tumultuous history of the region. On the other hand, it neglects to account for the intellectual structure, texts and spiritual premises of global jihad. It might even purport that jihadis were merely influenced by their environment, without being actively involved in the result that is the Islamic State. In other words, a contextual approach alone falls short in explaining the complex process out of which Daesh was born.

The second approach proposes that religious texts – in and of themselves – were the instigators of the phenomenon. This approach falls flat, however, in explaining how Daesh is such a recent occurrence while the texts are so ancient, and why these texts have not previously produced similar phenomena.

The third approach encompasses social and psychological factors. It focuses on the players – their social roots and environments, their experiences, and their psyche. But that approach, like the two before it, falls short in explaining the complexities of cause and effect. Are these people the products of their environments, or are they the effectors who created their own environments and their own circumstances? Could they possibly be both?

The fourth approach attempts to think outside the box by purporting that Daesh is an anomaly in the history of global jihadi groups, and, therefore, the usual analyses and their instruments just cannot fathom it. The problem with this perspective – in addition to the fact that it doesn’t actually offer a real approach – is the underlying belief that this so-called anomaly is so singular and unique that it can only be explained by its sheer brutality and its enigmatic, sudden structure. That singularity is open to debate, however, whether in light of the history of jihad or the history of brutal jihadi conflicts. But what makes the difference in the present case is the appeal of Daesh’s image and its propaganda.

As an alternative, this study proposes an approach that discards two popular ideas: the notion of the Islamic State’s unique singularity that isolates it from global jihad as a whole, and the notion that this singularity is a “label” or “stereotype” that can be attached to a particular line of thought, religion or group of people. This is embodied in the analysis of the ideological structure of the organisation (its roots, developments, origins and products), on the one hand, and the analysis of the complex reality in which this ideology appeared, on the other.

This approach is based on the premise that ideas are formed within complex contexts, to which they contribute and by which they are affected, through an intricate process where texts become inseparable from reality, regardless of which of the two came first in the mind of the jihadi, because such interchangeability can affect the nature of the relationship with both. Did the jihadi’s mind-set originate from the text, or is his soul, jaded by reality, seeking refuge in the ritual associated with the text? Does the text govern him, or is the text just a cover through which he seeks religious legitimacy? This reciprocity has no effect on the premise that the product is a compound that resulted from a reaction between the two, with many catalysts, some of which are psychological.

The only option in this approach is to go back to the original texts of the self-acclaimed "jurists" of global jihad (and to clarify, the term "jurists" is used loosely here), listen carefully to the statements of their leaders, and observe how things unfolded in their organisational relationships while analysing the global context on the one hand and the context of other Islamic movements on the other.

Daesh and the global jihad endeavour

IS cannot be separated from the ideological framework of global jihad, which is based on a number of foundational and minor aspects. The foundational aspect or origin, upon which all of global jihad’s organisations agree, is basically to rule by God’s word and establish Islamic Rule, which, according to them, can be achieved only through jihad. The absoluteness of this foundation produces all other concepts, details and courses of action, which we call minor matters or “branches”, around which differences revolve. Al-Qaeda, Daesh, and al-Nusra Front’s respective public statements have clearly brought these differences to light. The statements of Ayman al-Zawahiri, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, Abu Mohammad al-Adnani and Abu Mohammad al-Jolani,(1) as well as the literature they disseminate, clearly demonstrate this.

The verbal and written bickering between IS and al-Qaeda is ideal material for analysis. First, the material depicts agreement more than it does disagreement. The statements of both rivals show that they agree on the principle of setting up the “Islamic State in Syria” and then declaring it a “caliphate”, as in Zawahiri’s statement,(2) and that this endeavour collides with two other endeavours - one that seeks a civil, democratic and secularist state, and another that seeks a nation-state that, though it would call itself Islamic, would inevitably acquiesce to the “tyrannical” West and derail jihad, according to Adnani.(3) All of them agree that secularism, nationalism, patriotism and democracy are “clear infidelity and apostasy that contradicts Islam and leads to excommunication”.(4)

The reciprocal exchanges between Adnani and Zawahiri, which appear to have went on as late as January 2014, outline the relationship between IS and al-Qaeda.(5) They show that Zawahiri considered Daesh part of al-Qaeda, because it had pledged allegiance and followed orders as pertaining to jihad. According to Adnani, however, all these concerns are matters “outside the borders of the Islamic State”. The latter added that Daesh’s breakaway from al-Qaeda was due to methodological reasons and that al-Qaeda “is no longer the base of jihad”, and its leadership “has become a thorn in the side of the Islamic State project and, by God’s grace, the upcoming caliphate”.(6)

Despite Adnani’s attempt at labelling the rift as a methodological one, it is clear that this rift is not about visions and principles as much as it is about organisational and practical issues. Daesh wasn’t happy with Zawahiri distancing himself from the battlefield, nor with what seemed to be al-Qaeda’s compromise in jihad in a move towards “appeasement”.(7) In fact, the entire conflict revolves around the issue of declaring “the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria” and the inclusion of al-Nusra Front in the first place, and then on the timing and manner of declaring the “caliphate”.(8) That practically amounted to IS declaring itself free from Zawahiri’s monopoly on global jihad, which, in the eyes of IS, is a right he no longer had, what with his distance from the battlefield and his loss of control over jihadi groups’ daily activities. It is to this breakaway that Daesh attributes its achievements on the ground, paving the way for the declaration of a singular caliph who would renounce tyranny, infidelity and the infidels, instead ruling by God’s word. This was the solution proposed by Adnani to address the splintering and discord among jihadi groups that he says were caused by Zawahiri.

Abu Qatada al-Filistini reveals that there had been “messages and conversations” between Abu Muhammad al-Maqdisi and the Islamic State. Abu Qatada says he realised that “the declaration of the caliphate would do away with the discord between (Daesh) and its opponents over the leadership of jihad and give it legitimacy (jurisprudence of tyranny)”.(9) In his response to Daesh, he expressed qualms not over project’s conception, but over the details of its execution and the manner in which the caliphate should be established.

In these letters, Abu Qatada also says deviation infiltrated Daesh from two fronts: on the one hand, there were the inexperienced members of the pro-caliphate groups, and on the other hand, there were remnants of Jihadi and other extremist factions. The former were keen to gain his endorsement of their idea that the reason for corruption is the absence of a caliphate, and that this could be brought about by pledging allegiance to a Muslim who is a descendent of Prophet Mohammed, the idea adopted by Daesh. The latter group contained remnants of the more fanatical groups that participated in jihad and went on to plant deviant ideas in the minds of young people who had embraced Islam and the non-Arabs who embraced Islam with little or no knowledge of Shariah.(10)

The "deviation" to which Abu Qatada referred in this response, which he wrote at Maqdisi’s request, is reminiscent of what happened in 2004, when Maqdisi had written a similar letter to Abu Musab al-Zarqawi, the spiritual father of the Islamic State, which he titled “To Zarqawi: Support and Advice”.(11)

The core of that repeated “deviation” in both Zarqawi and Baghdadi’s cases rests upon two issues:

-

Breakaway from the guidelines of jihad that had been set by al-Qaeda’s spiritual leaders: This encompasses the concept of jihad and avoiding turning it into a vendetta-driven struggle for revenge, avoiding influencing “jihadi choices” by enemy pressure and brutality, judicious use of excommunication, and taking into account the differences between the real “land infidelity”, in which the majority of residents are infidels, and the technically-named “land infidelity”, whose residents are mostly Muslims.

-

Rigid Daesh leadership structure: Zarqawi’s lack of resilience “deprived him of assimilating into al-Qaeda and coming under the command of Sheikh Osama [bin Laden]”, Maqdisi wrote in his letter. He further points out that Abu Anas, whom Zarqawi consulted with, “would not have taken our choices completely to heart”. This is the same situation we saw between Baghdadi and Zawahiri.

What’s peculiar is that, in Zarqawi’s case, Maqdisi had written that failure to adhere to the guidelines of jihad as set by its reference (i.e. al-Qaeda) would produce groups that “heed no rules in fighting, and would go against the nation, not discriminating between the good and the bad, and failing to strike a balance between its interests and shortcomings”.

Similarly, in the case of Baghdadi, Abu Qatada saw that Daesh had disadvantaged the jihadi cause in two ways: it caused a split in the (jihadi) endeavour, and it turned the conflict into infighting, to the point that within a mere six months, Daesh’s conflict with al-Nusra Front turned from a dispute over emirship to an all-out religious war (12) because it had declared itself a caliphate over an imaginary group of Muslims rather than a real one.

The mere idea of “radicalism and deviation” in and of itself does not offer sufficient reason to believe that IS is completely different from al-Qaeda. If anything, the group is the progeny of the conceptual world of global jihad and an extension of the guidelines set by central leadership. These guidelines are in response to the capabilities made available by the jihadi endeavour itself, as well as the developments on the ground, the difference over the best ways to accomplish that endeavour, and the struggle over the emirship, which is central to these kinds of movements in general. The series of extensions from the “Islamic jurisprudential system”, which the spiritual leaders of global jihad started, do not stop at the limits they drew for themselves and their followers. Creating an extension, by its very nature, is serial, and can only lead to more fragmentation, which is common among these groups that adopt their own interpretations of the broad guidelines they operate within, and eventually “break away” from.

“Unique singularity” of Daesh

Professing the uniqueness of the movement has only served to increase the mystique and complexity surrounding Daesh. The idea of IS being “unique” and “singular” is based on a number of considerations:

-

The change in al-Qaeda’s behaviour, confirmed by the documents found on Bin Laden’s computer by the Americans– that change was particularly evident in al-Nusra Front’s actions in Syria.

-

The rigid, tense vision that puts forth the spiritual, sectarian and identity aspects of jihad.

-

The sheer magnitude of IS’ brutality, which forced even al-Qaeda to criticize its radicalism and excessive excommunication.

These considerations – assuming they are taken as constants – indicate a change not in the endeavour, but in its policies. In his exchange with Zawahiri, Adnani explicitly asserted that Daesh would adhere to the path of al-Qaeda before Zawahiri’s ostensible change. From the statements of Baghdadi and Adnani, that original path is that “[jihadis] shall not let go of [their] weapons until there is deferment to Shariah”, that they “shall fight for an Islamic state”, that the regimes and armed forces Zawahiri defended are all infidels, and that jihad (as it is understood as armed, violent struggle) is a duty.(15) Zawahiri’s letter to Zarqawi in October 2005 outlines the phases of the endeavour as conceived by the former: it starts with expelling the Americans from Iraq, then establishing an Islamic emirate that would be nurtured and developed into a caliphate that would control as much of Iraq as possible, especially the territories inhabited by Sunni Arab, then spreading this wave of jihad to neighbouring secular states, and finally “confronting Israel, because Israel was created only to thwart any emerging Islamic entity”.(16)

The difference between Daesh and al-Qaeda manifests itself in their approaches to politics: the shrewdness of al-Qaeda versus the belligerence of Daesh. One of global jihad’s stated aims is to establish an Islamic state, and the only way this can be achieved is through jihad. The doctrine of al-Qaeda in Mesopotamia is that “jihad is ongoing until the Day of Judgment, with or without an imam [leader]… and every believer must wage jihad against the enemies of God Almighty even if he was the last man standing”. If an imam puts jihad on hiatus, individuals and groups must press on with this duty, and their doctrine also prioritises the enemies: “Rafidah [Shias] are people of polytheism and apostasy… and fighting the apostates takes priority over fighting born infidels”.(17)

Jolani, al-Nusra’s leader, labelled the struggle as one “between Muslims [on one side] and the Jews and crusaders on the other, and finally Shias and global superpowers [on the third side]”, adding that it is “a sectarian struggle”.(18) The aforementioned letter by Zawahiri indicates that though he agrees with Zarqawi on the labelling of the Shias, he sees no benefit from targeting them, and that it is in the best interests of al-Qaeda and Iran to not clash with each other, especially since there are about a hundred al-Qaeda members imprisoned in Iran.

It is intriguing to analyse the contradictions in Daesh’s definitions. While some might see it as hard-line and rigid, others may view it as pragmatic (albeit not so towards its fellow jihadis). In reality, both al-Qaeda and the IS are as hard-line or pragmatic as circumstances dictate, with both employing more or less the same logic. For instance, al-Qaeda was pragmatic in entering into a truce with Iran after the Afghan war. Daesh itself deferred to “the orders by al-Qaeda not to engage in hostilities towards the Rafidah in Iran, so as to uphold the interests of al-Qaeda and maintain its supply lines”, according to Adnani.

However, IS did not adhere to that order within the territories it controls, thus indicating that this hard line only manifests itself in cases that go against the established rule. It can be understood, then, that the group is only pragmatic when it is to their advantage and will not impede their interests. This explains why, when IS declared the caliphate, it labelled its opponents as tyrants that should be treated as such. However, al-Qaeda argues against the legitimacy of this caliphate, saying that Daesh reneged on its allegiance to Zawahiri. The conflict turned from one of politics to one of doctrine. To Daesh, the caliphate means that they are the “Muslim populace”, while all others are non-Muslims – a crucial tenet of the doctrine of global jihad rather than an anomaly of it.

It should be pointed out that with the occupation of Iraq, al-Qaeda changed from a hierarchical organisation into an idea – a project whose strategy and dogma changes according to its membership and how things develop on the ground. This was made especially clear in Zarqawi's letter to Bin Laden in January 2004,(19) in which he deemed it necessary to target “the sects of apostasy” and not suffice with waging war against the “remote enemy” (i.e. the Americans). Zarqawi brought in new techniques of warfare to jihad, such as increased suicide attacks, slaughters, and excessive labels of apostasy; and then in October 2004 he pledged allegiance to al-Qaeda's branch in Iraq and its leader, which effectively meant that al-Qaeda's leadership had embraced – or at least accepted – the new development.

The two most prominent issues in the quandary of understanding the Islamic State are its brutality on the one hand, and its surprising ability to expand and capture new territories on the other. For sure, the many former Baathist officers who joined Daesh between the eras of the two Baghdadis (Abu Umar and Abu Bakr) played a significant role in these respects. But this brutality started with Zarqawi, whom Zawahiri had warned in his 2005 letter of how the “scenes of slaughter” would be detrimental to “winning over the hearts and minds of our nation (Ummah)”. The legitimisation of “roughness and toughness” is attributed to two major figures: Abu Abdullah al-Muhajir (formerly Abdurrahman al-Ali) and Abu Bakr Naji.

Muhajir’s book on the dogma of jihad greatly influenced Zarqawi, who actually studied the book under Muhajir. More a book about the dogma of blood, Muhajir posits that any country deferring to the rule of positive law is a land of infidelity that Muslims are obligated to leave. He also wrote that there is absolute consensus on the unconditional bloodshed of an infidel unless he or she is under the protection of circumstances stipulated by Shariah. He adds that siding with apostates against Muslims is the greatest infidelity of all, and that Islam does not differentiate between military and civilians. He wrote that “the brutality of beheading is intended, even delightful to God and His Prophet”.(20) Muhajir is an Egyptian national who graduated from the Islamic University in Islamabad and participated in jihad in Afghanistan and taught at jihadi camps in Kabul. He ran teaching at Zarqawi's camp in Herat, and was a candidate to take over the scientific and scholarly committee of al-Qaeda. He was held in Iran and then released to return to Egypt just after the revolution.

As for Abu Bakr Naji, he believes that jihad is one of the primary ways to lead people to Islam. He says that jihad is “brutality, terror, displacement and massacre”, and that “Shedding the blood of the People of the Cross, their apostate supporters and their soldiers is an absolutely (sic) prime duty. Today we are in a situation similar to that of early apostasy and the beginnings of jihad, therefore, we need massacre and to do just as has been done to Banu Qurayza [massacring their men, the taking their women and children as spoils, and taking their possessions], so we must adopt a brutal policy in which hostages are brutally and graphically murdered unless our demands are met”.(21)

As for the speed and efficiency with which the Islamic State managed to capture and control new territories, that can only be understood through the context of the changes that swept through the region in the period between the Afghanistan and Iraq wars and the Arab Spring. Daesh blew into the vacuum left behind by the weakness of nation-states and the tyranny that prevailed in Iraq after the occupation; as well as the utter brutality with which the Assad regime reacted to the Syrian uprising, which has turned it into an ongoing armed struggle. Jolani clearly stated that the Syrian revolution had “removed all barriers” and made the jihadi doctrine easier to embrace, and people started to bear arms after they “were not receptive to our method”.(22) The primary reference that put this strategy forth was Abu Bakr Naji, who used the term “the management of lawlessness” (which is also the title of his book) to label a condition in which a given state collapses and the country becomes lawless, paving the way for other forces (in this case their version of Salafi jihadism) to move in and take over, restore order and shoulder responsibilities such as managing the needs of the population, establishing security, settling disputes and securing borders, among other things.

Naji applies this strategy to an even broader context. In his diagnosis of the problem, he starts with the fall of the Ottoman caliphate, the ratification of the Sykes-Picot agreement, and the new world order after World War II. In his opinion, this brought about regimes imposing values contradictory to those of their societies and against their religion, wasting their wealth and spreading injustice. He adds that ignorance of God's word took hold of the world through systems of citizenship, banknotes and borders. Islamism – according to him – would eventually rise from the ashes of the United Nations and lead the Muslim nation out of its debasement and lead mankind to enlightenment. Naji proposed that the only endeavour qualified for all this is Salafi jihadism, because it is the only one that is godly and has a comprehensive vision for running worldly affairs according to Shariah. He is critical of four other endeavours: Sahwa (awakening) salafism (of which Salman al-Ouda and Safar al-Hawali are primary figures), which he sees as identical to the doctrine of the Muslim Brotherhood; the Muslim Brotherhood itself, which he called “rotten”; the Hassan al-Turabi-led Brotherhood, which he believes promoted secularism by adopting worldly values and discarding godly ones; and the popular jihad movement (embodied by the likes of Hamas and the Moro Islamic Liberation Front, which he believes are infiltrated by the Muslim Brotherhood).(23)

Ideological structure of global jihad and its doctrinal system

“Ruling in accordance with God’s word” is global jihad’s doctrinal core. Towards that goal, it builds its visions and the legitimacy of its actions upon what it calls Shariah (Islamic divine law), which – according to it – is synonymous with fiqh (Islamic doctrine). When some commentators blame widely-misunderstood and misinterpreted Islamic doctrine for all the atrocities that are undertaken in the name of Islam, they really actually fall into this very trap of the jihadis’ erroneous vision. While the Muslim Brotherhood and Daesh are diametrically opposite, they both draw on the same Islamic jurisprudence. In other words, religious texts and jurisprudence, in and of themselves, cannot explain the emergence of phenomena like Daesh, particularly given that the texts are centuries old as opposed to these new jihadi-political groups who use them to legitimise their existence.

One cannot ignore the fact that the Muslim Brotherhood that began the trend of politicising religion, hoping this would compensate for the Ottoman caliphate’s fall by setting up an Islamic state that rules according to Shariah. Thinking this would be a precursor to setting up another caliphate, the group sought to build a comprehensive Islamic regime that would go against the prevailing regimes in various aspects. Through Sayyid Qutb, who posed ideas like “Jahiliyya" (type of ignorance widespread in the pre-Islamic period) , “divine sovereignty”, and the excommunication of entire societies, the Muslim Brotherhood’s ideas found their way to and permeated global jihad. However, in order to achieve the same goal, global jihad used methods and instruments that were contrary to what the Brotherhood originally intended. They even added a third kind of Tawheed (unity of God) to Ibn Taymiyyah’s original two: Unity of Godhood (uluhiyya), Unity of Lordship (rububiyya), and the unity sovereignty (hakimiyya). Given all of this, it can be said Qutb was the source of all jihadi thought, from Abdullah Azzam and Zawahiri to al-Nusra Front and Daesh’s scholars.(24)

In the eyes of global jihad adherents, the concept of “ruling in accordance with what God revealed” begins with excommunication first, then branches out to the apostasy of rulers who govern according to the rule of positive law, the apostasy of those who accept such rule, and the apostasy of those who don't excommunicate them all. It also posits that the countries in which the rule of law prevails are lands of infidelity, where Islam is alien, and therefore there should be “wars of apostasy” just like in the early history of Islam, and thus jihad becomes a pillar of Islam. The second part of that concept outlines a course of action that must be taken by the “elite of jihadi believers”, which is to disobey infidel rulers and to fight them regardless of whether or not we have the power to do so.(25) The third part says that the commands of all those infidel rules must be cast aside as null and void in the eyes of Shariah, and that includes contemporary laws, treaties, and political systems. The last part is the rule of Islam, the implementation of Islamic Sharia, and the declaration of a caliph.

This system would not have been possible without discrediting most Islamic scholars, institutions and sources of Islamic science, and selectively taking texts out of their context by following specific "jurists" who come from outside the Islamic mainstream. Since the mainstream does not help them in this regard, they appear to be keen to write out their vision for jihad differently and in an extremely selective way, so much so that Abu Abdullah al-Muhajir made the concept of dividing the world into lands of Islam and lands of infidelity part of the essentially recognized part of Islam,(26) and then went on to excommunicate anyone who disagreed with him. Conversely, the overwhelming majority of Muslim jurists see this division as one imposed by historical events that no longer exist.

On the other hand, the mainstream Islamic doctrine says that “ruling in accordance with what God revealed” isn’t nearly as simple as global jihad adherents make it out to be. When Ibn Abbas, an early Islamic scholar, cousin and companion of Prophet Mohammed was asked about the Quranic verse, “And whoever does not judge by what Allah has revealed - then it is those who are the disbelievers” (Al-Maidah, verse 44), he said, “Their infidelity is not the same as that of him who denies God and the Day of Judgment”.(27) Ataa bin Rabah, also a prominent early Islamic scholar, said that infidelity, debauchery and injustice all have degrees. Ahmad bin Tawoos (also an early Islamic scholar) said that ruling according to laws other than God’s word, though to some degree an act of infidelity, does not necessarily render its practitioners non-Muslim. What he meant was that ruling according to other laws may either be in sheer defiance of God's word – with its guardians believing that their laws are equal to or better than those of God's or simply rejecting God's ruling – or may be it is not an expression of sheer defiance of God's word when it is based on discretional interpretations out of ignorance, under duress or something similar. Moreover, Shariah poses absolutely no connection between excommunication as a precondition for faith on the one hand, and robbing an infidel of his or her rights just for being an infidel on the other.

Islamic Shariah (divine law) recognises the legitimacy of a ruler as long as he gains power by one of three ways: choice, allegiance, or conquest (as in giving legitimacy to something that cannot be alleviated, not as in setting up laws that make conquest possible.) Shariah also states that a ruler shall not be excommunicated unless he clearly and unequivocally states his own apostasy. If, however, he issues rulings that coincide with Shariah, then his rulings must be followed, and if he goes against Shariah, he shall not be obeyed, and his ruling shall be protested according to the rules that govern disobedience in Shariah.

According to the Shafii school of thought – the most stringent of the four Sunni schools of thought, which sees infidelity as the forerunner to jihad – jihad is a duty of means, not ends. The objective of waging war is to spread the word of Islam, if no other means are possible. Fighting the infidels, in and of itself, is not the objective – if one can spread the word of Islam by evidence and proof, then jihad becomes superfluous and unnecessary.(28)

Shariah (divine law) is not the same as fiqh (jurisprudence). Shariah includes the rulings of God, making it indisputable and proven in definitive texts and prompting scholars to concur that Sharia is unalienable. Fiqh, however, is the product of the human interpretation of Shariah, and is governed by the four factors of time, place, context and individuals. So, Shariah laws are either derived directly from the texts of Qur'an and Sunnah (whether explicit or implied) or they can be deduced from understandings of facts as they relate to these texts. As such, Fiqh (interpretations) may be different according to time and place.

It must be pointed out that some of the issues upon which the jihadis based their doctrine rely on certain fatwas by Najdi imams. One of those issues is government by earthly laws. Najdi imams, from Mohammed Bin Abdul Wahhab to Mohammed Bin Ibrahim, the grand mufti of Saudi Arabia, excommunicate those who make and apply these laws. Therefore, the spiritual leaders of global jihad used these fatwas to their advantage. Al-Muhajir quoted Bin Ibrahim as saying that those who pass earthly laws must be excommunicated, and that Muslims should leave countries where such laws are passed, because they are no longer home to Islam. He and Abu Bakr Naji also quoted from Sulaiman Bin Sahman, another Najdi imam. Abdulaziz Bin Baz was the first one among them to issue a fatwa that said that those who make laws are not absolute infidels, for they might have done so out of weakness, desire or deduction. Also among Najdi imams, there is talk of turning away from infidels, calls to fight them, to “cleanse one's self with the blood of the infidels and apostates”, that “jihad is a pillar of Islam”, “jihad does not need a leader,” and “that religion can only be supported through jihad”,(29) and many other similar fatwas of excommunication and rising against rulers. This is why such fatwas were outlawed in Saudi Arabia.

Summary

This study argues that any approach worthy of consideration must begin with shedding the notion of Daesh’s unique singularity that separates it from global jihad, and must also break free of the idea that such singularity is a label that can be attached to a particular line of thought, religion or group of people. This is embodied in the analysis of the ideological structure of the organisation (its roots, developments, origins and products), on the one hand, and the analysis of the complex reality within which this ideology emerged, on the other. The idea of “radicalism and deviation” prompts us to conclude that conceptually, the Islamic State is global jihad’s progeny and a divergence from the guidelines set by the central leadership. This divergence occurred in response to developments on the ground, the differences over the best ways to accomplish the goals of the movements, as well as the struggle over the emirship itself, which is central to such movements in general. The series of divergences from the “Islamic fiqh system” drawn by spiritual leaders of global jihad will not stop at the limits Daesh has drawn for themselves and their followers.

“Ruling in accordance with what God revealed” is the core doctrine of global jihad. Towards that goal, it builds its visions and the legitimacy of its actions upon what it calls “Shariah” (divine law), considering it synonymous with Fiqh (Islamic jurisprudence). So, when some commentators blame the widely-misunderstood Islamic doctrine for all the atrocities that are done in its name, they actually fall into the trap of the jihadis’ erroneous vision. The very same possibilities enabled by that Islamic doctrine are the ones used by the Muslim Brotherhood, which is the diametrical opposite of groups like Daesh. In other words, ancient religious texts, in and of themselves, cannot explain the new emergence of phenomena like the Islamic State.

The speed and efficiency with which the Islamic State managed to capture and control new territories can only be understood in the context of changes that swept through the region during the period between the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq and the Arab Spring. Daesh blew in to fill the vacuum left behind by the weakness of nation-states and the tyranny that prevailed in Iraq after the occupation, as well as the utter brutality with which the Assad regime responded the Syrian uprising, which has turned into a prolonged armed struggle.

Daesh is the product of complex contexts in which religious texts and reality intertwine, and it is a development of global jihad rather than an aberration of it.

___________________________________________

*Dr. Motaz al-Khateeb is assistant professor of ethics methodology at the Research Centre for Islamic Legislation & Ethics (CILE), Qatar Faculty of Islamic Studies (QFIS), Hamad Bin Khalifa University.

Endnotes

1. Zawahiri audio recording released 12 October 2013; Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi’s announcement of merging al-Nusra with Daesh, 9 April 2013; Abu Muhammad al-Adnani audio recording, 30 July 2013; and Jolani interview on AlJazeera, 19 December 2013. Also see the Islamic States’s doctrine and methods on theshamnews.com.

2. Zawahiri audio recording, 12 October 2013.

3. Adnani audio recording, 30 July 2013.

4. The same idea recurs in multiple statements and writings. For example, see Doctrine of al-Qaeda in Mesopotamia and Abu Maria al-Qahtani’s interpretation of it, Nur Al-Yaqin, (Dar al-Jabha for Press and Publication), 27. See also Baghdadi's 9 April 2013 recording, in which he says, “Do not get rid of the injustice of dictatorship for the sake of the injustice of democracy”, as well as Jolani’s 24 February 2014 recording, in which he mentions groups that became apostates and infidels, such as the Syrian coalition and those in charge of the “national army” project. In an interview with Sami al-Auraidi, the spiritual leader of al-Nusra on 21 October 2013, he divides rule into two categories: godly and jahili (ignorant). He added that most (jihadi) groups want to rule according to God's word and establish a Muslim state; the ones that want a secular civil state are few, and “we call upon them to come back to reason and learn their lesson”.

5. Abu Muhammad al-Adnani, “This Has Not Been our Method and Shall Not Be”, statement, 17 April 2014, followed by Ayman al-Zawahiri's response on 2 May 2014, followed by Adnani's reply titled, “Excuse me, emir of Al Qaeda”, 11 May 2014.

6. Ibid.

7. In a statement on 31 August 2013, Adnani says, “Appeasement is not the way of the Prophet and leads to no good”, adding that now that the Islamic State has been declared, the “duties” of immigration and jihad have become incumbent on all Muslims.

8. Daesh insisted on establishing their state, disregarding Zawahiri's demand to dismantle it and disengage IS in Iraq from Nusra in Syria. On 15 June 2013, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi publicly stated, “The state shall remain”, and Adnani's stated on 30 July 2013, “For the sake of establishing the Islamic State, we shall fight all who fight us”.

9. Omar bin Mahmour Abu Omar, “Abu Qatada in the Caliph's New Clothes”, Nukhbat Al-Fikr, 2014, 7. Abu Omar wrote this while in prison.

10. Ibid, 3 – 5.

11. Maqdisi letter to Zarqawi, written from Qafqafa prison in Jordan, 2005, http://www.tawhed.ws/r?i=dtwiam56.

12. Abu Qatada interview, AlJazeera.net, 12 November 2014,http://www.aljazeera.net/news/arabic/2014/11/12/%d8%a3%d8%a8%d9%88-%d9%….

13. Mohammed Aburumman, “This is How the Ideology of Lawlessness Came About”, Al-Araby Al-Jadeed, 6 October 2014,http://www.alaraby.co.uk/opinion/c2c162e1-7384-4891-9f2b-8346cb9c0d56.

14. Nawwaf Qudaimi, “How was ISIS Formed?” Al-Araby Al-Jadeed, 20 August 2014,http://www.alaraby.co.uk/opinion/99b08cd2-484b-4e94-850f-c2946ecb648e.Y… al-Haj Saleh also talked about this in his article, “Anomaly in Thought to Understand the Anomaly of IS”, Al-Quds Al-Araby, 29 October 2014,http://www.alquds.co.uk/?p=242548.

15. Abu Muhammad al-Adnani, audio recording, 31 August 2013. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=BeT4D3PpV6g.

16. The letter was published by John Negroponte, US Director of National Intelligence. Zarqawi was said to have denied its authenticity, but the details in the letter and current events have thus far confirmed the letter’s contents.

17. Quotes from Doctrine of Al Qaeda in Mesopotamia and its interpretation, Nur Al-Yaqin, 25, 28 and 31.

18. Jolani, AlJazeera, 19 December 2013. http://www.aljazeera.net/programs/today-interview/2013/12/19/%D8%A3%D8%A8%D9%88-%D9%85%D8%AD%D9%85%D8%AF-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AC%D9%88%D9%84%D8%A7%D9%86%D9%8A-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%86%D8%B5%D8%B1%D8%A9-%D9%88%D9%85%D8%B3%D8%AA%D9%82%D8%A8%D9%84-%D8%B3%D9%88%D8%B1%D9%8A%D8%A7.

19. The letter was published by the US government, Zarqawi's organisation vouched for its authenticity and republished it, Abu Maysarah al-Gharib, Zarqawi's PR man, and Abu Anas al-Shami, also corroborated it.

20. Abu Abdullah al-Muhajir, Issues in the Fiqh of Jihad, 8, 21, 34-38, 271 and 409.

21. Abu Bakr Naji (real name unconfirmed,) Management of Lawlessness: Ummah's Most Dangerous Phase, Centre for Islamic Studies and Research, 31-33.

22. Jolani, AlJazeera, 19 December 2013. http://www.aljazeera.net/programs/today-interview/2013/12/19/%D8%A3%D8%A8%D9%88-%D9%85%D8%AD%D9%85%D8%AF-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AC%D9%88%D9%84%D8%A7%D9%86%D9%8A-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%86%D8%B5%D8%B1%D8%A9-%D9%88%D9%85%D8%B3%D8%AA%D9%82%D8%A8%D9%84-%D8%B3%D9%88%D8%B1%D9%8A%D8%A7.

23. Abu Bakr Naji (real name unconfirmed), Management of Lawlessness: Ummah's Most Dangerous Phase, 3-17 and 76.

24. For more on Sayyid Qutb and armed groups, see Motaz Alkhateeb, Islamic Rage: Deconstructing Violence, (Damascus: Dar Al-Fikr, 2007). Sami al-Auraidi also mentions Qutb among prominent jihadi sources; and Qutb appears as a source in Naji's book.

25. Abu Maria al-Qahtani says in his explanation of the doctrine of al-Qaeda, “If the infidel leader’s toppling fell to one group, then they must bring him down him”, Nur al-Yaqin, 33.

26. Abu Abdullah al-Muhajir, Issues in the Fiqh of Jihad, 16.

27. Sufyan Al-Thawri, Tafsir Al-Thawri, Beirut, 1983, 101.

28. Al-Kahteeb al-Sharbini, Mughni Al-Mohtraj fi Maarifat Alfaz Al-Minhaj (Sufficient Resource for Meanings of Qur'anic Terms), Beirut, 1994, vol. 6, 9.

29. Abdulrahman al-Najdi, Al-Durar Al-Sunniyah fil Ajwibah Al-Najdiyah, (Letters and answers to questions by Najdi scholars from the days of Mohammed bin Abdulwahhab to today), Cairo, 1995, vol. 8, 13, 18, 23, 199, and 201.

| Back To Main Page |