Balance of power is a fundamental notion in international relations. It is shifting in the Middle East, where post-Cold War American dominance is giving way to something still unclear. Russia and China are asserting themselves, even as Iran re-emerges, Turkey engages, and Saudi Arabia displaces Egypt as the Arab center of gravity. The Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS) and the Aljazeera Centre for Studies (AJCS) hosted a conference June 12 entitled “Shaping a New Balance of Power in the Middle East: Regional Actors, Global Powers, and Middle East Strategy.”

Ezzeddine Abdelmoula, director of research for the Aljazeera Centre, set the conference agenda with his opening remarks, emphasizing the need to understand the geo-political dynamics, the role of non-state actors, and the future balance. As he pointed out, “With the current trend and frequency of crises and conflicts in the Middle East, the US-Arab relations are drifting toward some uncharted territories of polarization, fragmentation, and hegemonic impulses of certain regional actors.”

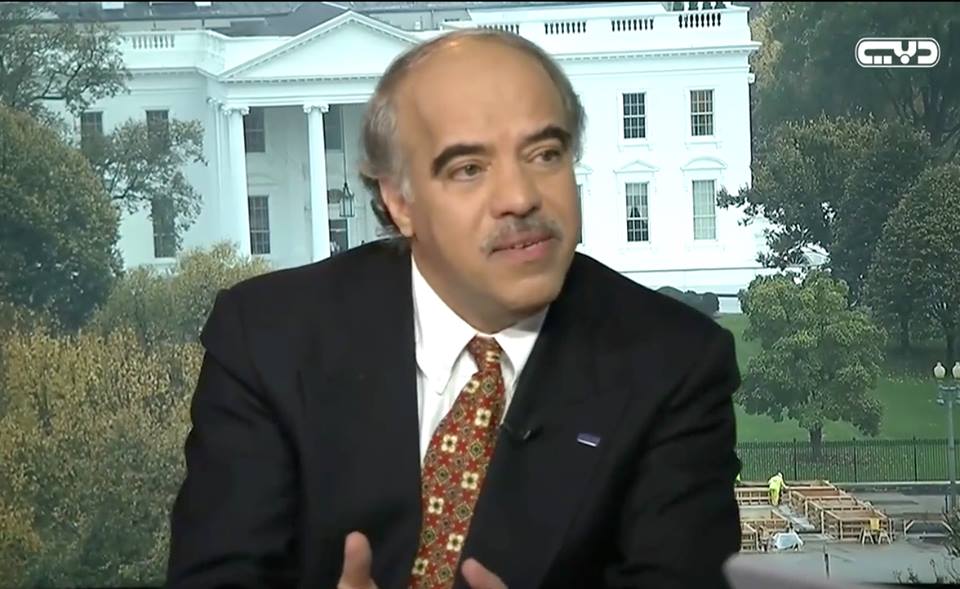

|

| Daniel Serwer, Director of SAIS Conflict Management Program delivering his welcoming remarks at the conference [AlJazeera] |

Panel one: Dynamics of Political Geography in the Middle East

Ross Harrison of the Middle East Institute argued that a “big bang” is occurring with recent civil wars, non-state actors, and great power interventions. From a comparative approach, he highlighted how the Cold War created Middle East balance of power. But with the fall of the USSR, balance of power has shifted. Former Soviet allies have struggled, although a “resistance front” of revisionist-regional powers, the involvement of international actors, and the role of Turkey, Israel and Iran have all served to counter potential US unipolarity.

Kadir Ustun, executive director of the SETA Foundation at Washington DC, argued that Turkey could not simply align with the West and hope for the best, nor could it duck regional developments. Instead, it has learned to diversify relationships and compartmentalize issues. Ankara’s top priority is to prevent PKK-aligned forces from gaining full control of northern Syria. Beyond that, Turkey wants an end to the Syrian war, calming of regional tensions, and continuation of the Iran nuclear deal.

Khalid al Jaber, director of the Gulf International Forum, bemoaned the worsening situation in the Arab world. The falling out in the Gulf between Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, and the UAE on one side and Qatar, Oman, Kuwait on the other is debilitating. Non-Arab regional powers are increasingly dominant, because Arab states are weak and divided. They lack legitimacy with their own people.

Addressing the elephant in the room, Suzanne Maloney of the Brookings Institution attributed Iran’s growing power to its success in making and keeping strategic partnerships, including with non-state actors. US efforts to counter Iran have failed: Tehran has pragmatically taken advantage of regional opportunities and now has no viable Arab rival. Nevertheless, Iran is running big risks from within. Its own population is dissatisfied and critical of both economic performance and foreign ventures.

|

| [From Left to Right]: Suzanne Maloney (Deputy Director, Foreign Policy Program and Senior Fellow, Brookings Institution), Khalid al Jaber (Gulf International Forum), Kadir Ustun, (Executive Director, SETA Foundation), and Ross Harrison, Non-resident Senior Fellow Middle East Institute and professor at Georgetown University), and Daniel Serwer (Director of SAIS Conflict Management Program) [AlJazeera] |

Panel two: Non-State Actors and Shadow Politics

Non-state actors and shadow politics are key players in the region, especially Hezbollah. Randa Slim of the Middle East Institute and Johns Hopkins SAIS portrayed it as not completely subservient to Iran nor entirely autonomous. A socio-cultural movement with military and social welfare wings, Hezbollah is primarily concerned with protecting itself but acts as a force amplifier for Iran on request. It splits its focus between keeping influence in its native Lebanon and growing its role as a regional power, which it views as defensive rather than offensive.

Fatima Abo Alasrar of the Arabia Foundation believes that in Yemen, non-state actors are more important than the state, which is weak and fragmented. The Houthis are a key component of Yemen and of any political solution, but their takeover of Sanaa precipitated Saudi intervention because the Kingdom feared the Houthis would act as a proxy for Iran. If Iran can be removed from the equation, peace would be more likely. Another key non-state actor to pay attention to are southern Yemeni secessionists. Decentralization and federalism could be answers to Yemen’s problems with both the Houthis and the South.

Crispin Smith, Harvard Law, discussed the proliferation of semi-state actors in Iraq, particularly the Kurdish peshmerga and Shia Popular Mobilization Forces. Both militias are seen as a monolith but in reality, they are fractured. Now nominally part of the Iraqi security structure, both still act independently of Iraqi government command and control and have violated international humanitarian law and human rights. As long as the US and international community aids these semi-state groups and as long as they stay independent, Iraq will continue to be unstable.

Anouar Boukhars of Carnegie’s Middle East program highlighted the surge of Quietist Salafist in Algeria. The Quietists claim to be an effective antidote to revolutionary ideologies and give disillusioned youth a purpose. Their message of opposition to violence while also advocating a conservative, theological society is popular, but the Algerian regime is unsure whether Quietist Salafism is a threat or a tool.

|

| [From Left to Right]: Anouar Boukhars (Carnegie and McDaniel College), Crispin Smith (Harvard Law School), Randa Slim (Middle East Institute and SAIS Foreign Policy Institute), and Daniel Serwer (SAIS Conflict Management Program), and Fatima Abo Alasrar (Arabia Foundation – at the podium) |

Panel three: New Balance of Power

What can be said about the new balance of power in the Middle East? Mohammed Cherkaoui of Aljazeera Centre for Studies and George Mason University focused on what he termed as three Ironies of the balance of power in the region: 1) global and regional powers have claimed they pursue a stable and promising Middle East. However, there is nearly fifty foreign military installations in the region. In 2018, the Middle East has the highest concentration of these bases in the world, being established by the Americans, the British, the French, Russians, the Turks, the Iranians, and even the Chinese in the Horn of Africa. 2) These global and regional powers have opted for various formulas of power.

The Middle East has become a magnet of hard power, soft power, smart power, and harsh power. 3) The exercise of power in the Middle East is no longer a linear process as was the case during the Cold War: one global power with several proxies or allies. Now, power in the region is hybrid relational alliances. Three years ago, no one of us could visualize a Russian-Iranian-Turkish pact. Trump’s America has invested in Mohamed Ben Salman’s Saudi Arabia, Mohamed Ben Zayed’s UAE, and Sisi’s Egypt. The question remains whether these coalitions are sustainable as a foundation of an alternative balance of power!

Jamal Khashoggi of Al Arab News Channel focused on the people or people politics. There have been battles across the Middle East between people power and regimes seeking to suppress it. In a region filled with failed states and chaos, the best solution is to listen to the people of the Middle East and their interests. P. Terrence Hopmann of Johns Hopkins SAIS looked towards cooperative security institutions like the OSCE (Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe) as an alternative to balance of power. This approach would face challenges in the Middle East because of the hard-bargaining, realpolitik mindset in the region. In addition, the OSCE, as a state-based institution, cannot provide a model for the many complex, non-state issues of the Middle East. Nor is there a clear mediator state in the Middle East to initiate an OSCE-like process.

Camille Pecastaing of Johns Hopkins SAIS discussed specific country situations. Egyptian power is dissipating. Turkey has limited power projection abilities. Saudi Arabia has potential in many major areas but needs to learn how to project power. Iran succeeds in power projection but is isolated with a tenuous economy. The US has been absent. It needs to decide its priorities regarding Middle East policy.

Urging a gradual and sequential approach, Hussein Ibish of the Arab Gulf States Institute argued that there are different levels of power imbalance in the Middle East. The Saudi Arabia/Iran balance is perhaps the easiest to resolve. The Islamist/secularist balance will be harder. Political Islam is still a big challenge that requires distinctions between violent and nonviolent actors. But, the toughest imbalance to right is between the people and their states.

|

| [From Left to Right]: Jamal Khashoggi (Al Arab News Channel), P. Terrence Hopmann, Professor of International Relations, SAIS), Camille Pecastaing (SAIS. Middle East Studies Program), Hussein Ibish (Arab Gulf States Institute) and Mohammed Cherkaoui (Aljazeera Centre for Studies and George Mason University) |