|

| [AL JAZEERA] |

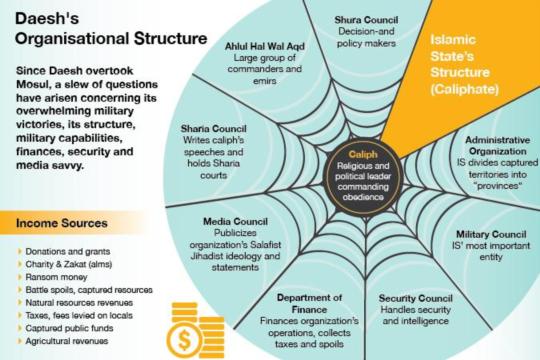

| Abstract Mosul’s takeover by Daesh, also known as the Islamic State or IS, prompted a flurry of questions on reasons for the group’s overwhelming military triumphs against official state armies as well as armed militias. This study examines one of the group’s key strengths: its organisational structure, including its military, economic, security and media arms. Tracing its structural evolution from Zarqawi’s leadership to its present structural manifestation under Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the report concludes that despite Daesh’s continued sophistication in fine-tuning its organisational structure, this does not mean that it does not face challenges, particularly given the formation of an international coalition which has begun striking the group in Iraq and Syria. This third chapter of the dossier chronicles the structural changes that shaped the Islamic State into what it is today, tracking the organisation from its roots under the name “Group of Monotheism and Jihad” (Jamaat at-Tawhid wal Jihad), to its declaration of allegiance to al-Qaeda, to its subsequent declaration of the Islamic State of Iraq after its leader, Jordanian Abu Musab al-Zarqawi was killed, and finally to its current form under Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi and his self-proclaimed caliphate. |

Introduction

The tremendous capabilities demonstrated by Daesh since it ravaged the Iraqi city of Mosul in June 2014 have raised numerous questions regarding the factors behind its overwhelming military triumphs against its self-declared enemies. There are several examples of this: four entire divisions of the Iraqi army fell with alarming ease to the Daesh’s forces in several Iraqi cities and regions. The same fate met the Syrian military’s Seventeenth Division in ar-Raqqah and the Tabaqah military airfield. The Kurdish Peshmerga succumbed to the Daesh’s might before the US Air Force intervened on 8 August 2014. Rival armed militias in Syria, such as the Free Syrian Army, the Islamic Front, al-Nusra Front, and many others, have all had to retreat in the face of the IS’s military power, which has barely been dented by an international coalition’s air strikes on Syria starting 22 September 2014.

The group’s effectiveness is not confined to their military capabilities. Economically, Daesh has more financial resources at its disposal than all the other jihadi and Islamist organisations combined, which implies that a professional, well-established entity manages this aspect, a vital one for the success of any organisational or institutional effort.

The same applies to security. The group has successfully carried out operations that required high levels of meticulously-detailed, professional-grade intelligence gathering. This was clearly manifested in Mosul, as well as in the assassinations of their rivals’ leaders. The IS demonstrated knowledge of the security details of each group’s higher echelons, including those that are being hunted down by some of the world’s leading regional and international intelligence agencies who use state-of-the-art surveillance technologies and techniques.

Moreover, the IS has revealed sophisticated media and PR capabilities that other Salafi-jihadi and Islamist groups have not managed to master. Their savvy use of the Internet in recruitment, propaganda and mobilisation, as well as the high production quality of their videos, in both English and Arabic, and their professional-quality magazines, have quickly become case studies in academic circles.

This study aims to chronicle the structural changes that shaped the Islamic State into what it is today, tracking the organisation from its roots under the name “Group of Monotheism and Jihad” (Jamaat at-Tawhid wal Jihad), to its declaration of allegiance to al-Qaeda, to its subsequent declaration of the Islamic State of Iraq after its leader, Jordanian Abu Musab al-Zarqawi was killed, and finally to its current form under Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi and his self-proclaimed caliphate.

The objective of delving into the group’s inner workings and its various departments is to shed light on the dynamics and institutions that enabled its vast capabilities and their sheer efficacy. It is also to learn more about the manpower and functions at Daesh’s disposal. This, in turn, could provide new perspectives that will help explain how the once-dubious group was able to achieve this level of professionalism on so many dimensions.

“Group of Monotheism and Jihad”

On the eve of the US invasion and subsequent 2003 occupation of Iraq, Zarqawi worked hard to rebuild his jihadi network from a solid foundation that had already been established in the Afghanistan’s Herat province. He began by building an inner circle of his most loyal followers. The most prominent among them were Abu Hamza al-Muhajir, an Egyptian national who took over the group after Zarqawi’s demise; Abu Anas al-Shami, a Jordanian who became the group’s first spiritual advisor; Nidhal Mohammed Arabiat, another Jordanian from the city of Salt, who was considered the group’s top bombmaker and thought to be responsible for most of the group’s car bombs; Mustafa Ramadan Darwish (also known as Abu Mohammed al-Libnani), a Lebanese national; Abu Omar al-Kurdi; Thamer al-Atrouz al-Rishawi, a former Iraqi military officer; Abdullah al-Jabouri (also known as Abu Azzam,) also an Iraqi; Abu Nasser al-Libi; and Abu Osama al-Tunisi. All of them were killed in 2003 except Abu Azzam, who was killed in 2005. Among the Jordanians most trusted by Zarqawi were Mowaffaq Odwan, Jamal al-Otaibi, Salahuddin al-Otaibi, Mohammed al-Safadi, Moath al-Msoor, Shehadah al-Kilani, Mohammed Qutaishat, Munther Shihah, Munther al-Tamuni, and Omar al-Otaibi.(1)

To rebuild his network, Zarqawi employed the ideology, ideas and jurisprudence he had learned at the hands of his mentor, Abu Abdullah al-Muhajir, who had a profound impact on Zarqawi’s fighting doctrine and approach to jurisprudence.(2)

Zarqawi’s network grew and developed quickly, but never had a specific name and did not adhere to a clearly defined structure. According to Abu Anas al-Shami, Zarqawi had been waiting for a home-grown Iraqi group to emerge, within which he would operate, but al-Shami suggested giving the existing group structure and the name “Monotheism and Jihad”. After some hesitation on the part of Zarqawi, who had been operating through a Shura council made up of members of his inner circle, he finally took to the idea of going public with the group. From then on, all audio, video and printed statements and publications went out under the group’s new name.(3)

A clearly defined structure was devised, with Zarqawi and his Shura council as leaders. Zarqawi had no second-in-command at the time, but there were several committees, the most important of which were the military, communications, security, finance, and Shariah committees. The latter was headed by Abu Anas al-Shami, the committee’s first spiritual leader starting in late September 2003.(4)

“Organisation of the Base of Jihad in Mesopotamia”

After eight months of communications between “Monotheism and Jihad” and al-Qaeda, the latter (highly-centralised) organisation grudgingly accepted Zarqawi’s terms, enabling him to maintain his strategies and course of action. On 8 October 2004, Zarqawi pledged allegiance to Osama Bin Laden, shedding the name “Group of Monotheism and Jihad” and declaring the group’s new name as “Organisation of the Base of Jihad in Mesopotamia”.(5)

The organisation experienced considerable growth under Zarqawi’s leadership, with increasing flexibility. While he initially controlled the organisation with an iron fist, Zarqawi later delegated more and more of his powers in order to guarantee that the organisation would remain operational if he was killed. The organisation announced that Abu Abdul Rahman al-Iraqi would be Zarqawi’s deputy, thus handing leadership over to the Iraqi faction within the organisation. Meanwhile, the organisation developed a more clearly defined structure.

The second-in-command post, occupied by al-Iraqi, was created out of necessity, in order to maintain the integrity of the organisation. The deputy enjoyed the same power as Zarqawi, and had access to everything pertaining to the organisation’s operations. Zarqawi put al-Iraqi in charge of communicating directly with the Iraqis within the organisation, while Zarqawi himself handled communications with volunteer fighters from outside Iraq. The deputy was also in charge of the needs of the organisation’s various committees.

Abu Asiad al-Iraqi led the military arm of the organisation and was in charge of all operational, executive and support battalions, companies and platoons. The organisation announced the establishment of the Omar Corps, which was a direct response to the Shia Badr Corps. Military regiments began to follow a specific methodology in target selection that blended centralisation with decentralisation. For instance, most of the minor attacks that did not require significant numbers of fighters spread across several regions were left to the discretion of field commanders, but in coordination with the senior officers of battalions and regional emirs.

The organisation’s military forces were divided into battalions, companies and squads with various names. Some of them were named after prominent caliphs, such as the “Abu Bakr al-Siddiq Battalion”, “Omar Corps” and “Ibn al-Khattab Battalion”. Others were named after al-Qaeda leaders in the Arabian Peninsula, such as “Abdulaziz al-Miqrin Battalion”, or after prominent members of the organisation, such as “Abu Anas al-Shami” and “Abu Azzam al-Iraqi” (also known as Abdullah al-Jouri). Yet other battalions maintained their original names before joining al-Qaeda in Mesopotamia, such as ar-Rijal (The Men) Battalion. Al-Istishhadiyoon (Martyrs-To-Be) Battalion was one of the organisation’s most important military units.

There were several other units that had special ties to the upper echelons in the organisation. The Security and Reconnaissance Battalion was responsible for meticulous vetting of new recruits and gathering intelligence about people, places and elected targets of the organisation’s operations. They were also responsible for scouting occupying forces and the private contractors that provided them with security and logistical support, scouting US troop movements, their military tactics and the future plans of both the US and the government. The battalion recruited agents within the National Guard, the police, private contractors, transportation contractors, and other entities that had vital and sensitive positions.

The Shariah committee was responsible for research and provided answers to any religious issues that the organisation required addressed in order to justify their beliefs and actions, and to spread their doctrine. It issued a magazine called Thurwat al-Sanam. This publication described the organisation’s religious edicts and served its agendas.

Headed by Abu Maysara al-Iraqi, the communications department issued statements and made audio and videotapes that displayed a surprisingly high level of professionalism. It handled propaganda for the organisation, which played a significant role in recruiting new members.

The financial committee collected the funding required to bankroll their various activities. It relied on a network of activists who gathered donations from businesspeople and mosques not only in Iraq, but all over the Arab and Muslim world. The committee also managed finances from the sale of battle spoils won by the organisation, and the various taxes levied on locals in areas under their control.

Islamic State of Iraq’s organisational structure

When he was killed in June 2006, Zarqawi left behind a firm, strong and powerful organisation. His followers had grown more determined to build an Islamic state on the basis of their Sunni identity. Shortly after his death, “Hilf al-Mutayyabin” (Pact of the Exalted,) a coalition that gathered various movements, organisations and militias, as well as some Sunni tribes, into the Mujahidin Shura Council, was declared 12 October 2006.(6) A mere three days later,15 October 2006, the Islamic State of Iraq (ISI) was declared,(7) theoretically encompassing the Sunni Iraqi provinces of Anbar, Kirkuk, Nineveh, Diyala, Salahuddin, Babil and Wasit.

Abu Omar al-Baghdadi (formerly Hamid Daoud al-Zawi) led the ISI. The first ISI government was announced by Moharib al-Jabouri, ISI’s official spokesman,(8) and highlighted Iraqi dominance within the ranks of the organisation, with few other Arab and foreign elements. On 22 September 2009, the organisation declared a second government with a different formation.(9)

After Baghdadi and his minister of war, Abu Hamza al-Muhajir, were killed on 19 April 2010, ISI quickly replaced its leaders. In a statement by the Mujahideen Shura Council (10) on 16 May 2010, it was announced that Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi al-Husseini al-Qurashi would become ISI’s emir. Abu Abdullah al-Hassani al-Qurashi would be his deputy and prime minister, while Abu Sulaiman would replace Muhajir as minister of war.

Islamic State’s organisational structure (Caliphate)

Daesh or the Islamic State (IS) is widely considered to be one of the world’s most well-developed international jihadi movements in terms of structure and administrative effectiveness. The organisation blended the structures of traditional Islamic movements under the institution of the Caliphate, and the theories of imperial jurisprudence, which established a framework for a theological state based on power and authority. Modern organisational aspects, such as military-security, ideological and bureaucratic apparatus, were worked into it. Since Mosul’s fall, the number of fighters within Daesh’s ranks has multiplied, eventually exceeding 35,000 Iraqis and Syrians, as well as more than 9,000 Arab and Muslim foreigners. The core elite forces number around 15,000.(11)

The Caliph

The Islamic State’s structure utilises a mix of Shariah rules and more modern necessities dictated by the times. The caliph (who is required to be well-versed in Shariah, of Quraishi descent and able-bodied) has absolute power over all religious and worldly affairs in Sunni Islamic political history and imperial jurisprudence. As the religious and political leader, the caliph has the absolute obedience of his followers after being chosen by the Shura council and those who hold binding authority within the organisation (Ahlul Hal wal Aqd).(12)

Insofar as running day-to-day affairs and managing rule are concerned, the organisation sees itself as a fully-fledged state. Abu Omar al-Baghdadi, the organisation’s former caliph, was the one who devised IS’ basic structure. Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the current leader, further developed that structure on the basis of allegiance and obedience, thus solidifying the organisation’s centralised nature and the caliph’s ironclad control of its every aspect.

The organisation’s pyramid has the caliph at the apex. He has direct authority over so-called “councils”, a term which Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi employs as an alternative to the “ministries” used by his predecessor, Abu Omar al-Baghdadi. These councils are IS’s central leadership pillars. Baghdadi has sweeping powers in appointing and removing the heads of councils after consulting with the Shura council, the role of which seems to be primarily advisory. The final, indisputable decisions all lie in the hands of al-Baghdadi (formerly Ibrahim Awwad Ibrahim al-Badri al-Samerrai, an Iraqi national), whose absolute powers guarantee him the final say in the most critical aspects of decision-making.

Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi ensured that there was a strong Iraqi presence in all key positions of the organisation, such as the Shura, information and communication, and recruitment and fundraising councils, while confining Arab and foreign members to support functions. He retained semi-absolute authority in war and hostilities. He was also keen to replace his war ministry with a military council. Baghdadi kept sole control of the key organisational functions, such as security, intelligence, day-to-day management, the Shura and military councils, the information and communications department, spiritual guidance, and finance. He also has the power to appoint leaders and emirs in the Syrian and Iraqi provinces under Daesh’s control.

Under Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the organisation entered a phase of extreme secrecy and paranoia. Once he took over, he restructured the organisation, putting Salafis and former Iraqi Army officers in charge of the military, such as Haji Bakr and Abdul Rahman al-Bilawi, turning the military corps into a more professional, cohesive entity.(13)

At the same time, Baghdadi used Arab and foreign jihadis for spiritual functions, especially those who came from Gulf states, such as Abu Bakr (formerly Omar) Al-Qahtani, Abu Hammam al-Athari, (also known as Turki al-Banali or Turki Bin Mubarak Bin Abdullah), from Bahrain, and Othman al-Nazih al-Assiri, a Saudi national.(14)

Baghdadi put Turkmen from Tal Afar into key security positions, most prominently Abu Ali al-Anbari; and put Arabs and foreigners in charge of his media machine, led by Abu Mohammed al-Adnani, the Syrian spokesman for IS. Even though Baghdadi increasingly began to integrate more Arabs and foreigners into the leadership of IS after Mosul’s fall and after declaring himself caliph in June 2014, Iraqis still dominate the highest, most sensitive positions in IS’ upper echelons.

Shura Council

The Shura council is one of the Islamic State’s most important structures. Despite the organisation’s various changes since Zarqawi’s leadership, the Shura institution has remained significant from the era of Abu Omar al-Baghdadi, and into Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi’s reign.

Currently headed by Abu Arkan al-Ameri, the council grows or shrinks as circumstances and needs dictate, with members usually numbering between nine and eleven of Daesh’s senior leaders, who are appointed by Baghdadi on the recommendation of emirs and provincial rulers. It usually convenes to debate current affairs, critical decisions and policymaking.(15)

In theory, the council has the power to depose an emir. It holds the same traditional historical functions reported in Islamic political history. It does offer Baghdadi advice on war and peace decision-making, but its advice is nonbinding. Shura is confined to day-to-day affairs that were not explicitly covered by specific texts in the Quran and Sunnah, because Islam states that where a text is available, there would be no place for debate or Shura, unless the debate is about how the said text should be interpreted in terms of the affairs of the IS and those of the population, and in dealings with others. The Shura council also recommends candidates for governor positions and memberships of various councils.

The spiritual council enjoys special status within the Shura council given Daesh’s theological nature. It is headed by Baghdadi himself, and is made up of six members. Some of its basic functions are to monitor how other councils adhere to Shariah laws and recommend new caliph candidates in the event the current caliph dies, is captured or is somehow no longer able to run the organisation and the state due to illness or disability.

Ahl al-Hal wal Aqd (Those who loosen and bind)

Ahl al-Hal wal Aqd, literally translated as those who loosen and bind, is a deeply seated concept in Islamic political jurisprudence and resembles the idea of a modern-day parliament. This council can encompass a wide variety of members and supporters from amongst prominent people within the organisation, such as emirs, leaders, politicians and figureheads. Any members of the council must possess certain qualities, such as wide-ranging qualifications, knowledge as it pertains to the ability to lead, and known wisdom. Within IS, they are a wide variety of figureheads, leaders and emirs, including the Shura council. They appoint and pledge allegiance to the caliph. According to Adnani, Daesh’s spokesman, Baghdadi had been selected as Caliph after “the Shura council of the Islamic State met and debated the matter, after the Islamic State, with God’s grace, gained all the prerequisites for a caliphate, making it sinful to not pursue [this course]. Hence, the Islamic State, represented by its “those who loosen and bind”, decided to declare an Islamic caliphate and appoint a caliph, and pledge allegiance to the Mujahid Sheikh, the knowledgeable, worshipful, prudent descendant of the house of the Prophet, Ibrahim Bin Awwad Bin Ibrahim Bin Ali Bin Mohammed al-Badri al-Qurashi al-Hashimi al-Husseini”.(16)

Shariah Council

This is one of the most vital entities within the Islamic State, given its theological nature. Abu Ali al-Anbari was formerly responsible for security and spiritual guidance, but the council is now headed by Abu Mohammed al-Ani. Abu Anas al-Shami was the first to hold that portfolio in the Zarqawi era and the Group of Monotheism and Jihad. Under Abu Omar Al-Baghdadi’s leadership, it was held by Othman Bin Abdul Rahman al-Tamimi.

The body issues guidebooks and messages, writes Baghdadi’s speeches and statements, and provides commentary for the organisation’s videos, songs and other media. There are two departments within the body: The first one acts as the judiciary, which runs Shariah courts and the judiciary system at large, handles litigation, mediates in disputes, dictates punishments, and manages the promotion of virtue and prevention of vice. The other department is tasked with preaching, guidance, recruitment, propagation and monitoring media. The Shariah body’s staff is mainly non-Iraqi Arabs, particularly GCC nationals and other foreigners.

Media Council

Mass communication is a significant focus for IS, one of the few jihadi organisations that give considerable attention to the Internet and mass communication. Since its formative days, it has recognised the value of the media in spreading its political message and Salafi ideology. The concept of “electronic jihad” became a key function early on, in the days of the Group of Monotheism and Jihad and al-Qaeda’s Base in Mesopotamia.

The media council was first headed by Abu Maysarah al-Iraqi. At the advent of ISI in 2006, the position was held by Abu Mohammed al-Mashhadani as minister of information while Abu Abdullah Moharib Abdul Latif al-Jaburi was spokesman for the state. In 2009, Ahmed Al-Tai became minister of information. Today, a large committee headed by Abu al-Atheer Amro al-Absi runs the council.

Daesh’s media council has undergone considerable development in form and content, and has extensive support. Al-Furqan, an institution for media production, is older and more influential than many of the newer media production entities which belong to the organisation, such as al-Etisam Institute, al-Hayat Center, Aamaq Institute, al-Battar, Dabiq Media, al-Khilafah, Ajnad, al-Ghurabaa, al-Israa, al-Saqeel, al-Wafaa, Nasaaim Audio Productions, and a slew of other media agencies in the provinces under IS control, such as al-Barakah and al-Khair.

The body also publishes a number of Arabic- and English-language magazines, such as Dabiq and al-Shamikhah, and has established local radio stations, such as al-Bayan in Mosul, and another in the Syrian city of ar-Raqqah.The organisation runs online blogs in Russian and English. Media productions are translated into various languages, including English, French, German, Spanish and Urdu.

The organisation controls several websites and online forums, which offer a vast array of literature about its ideology, discourse, methods of recruitment, fundraising, training, covert activities, battle tactics, bomb-making, and everything jihadis need to know about combat, gang warfare and attrition.

The quality of videos and other material produced by institutions like al-Furqan and al-Etisam reveal significant changes in Daesh’s structure, resources, violent tactics, and terrifying strategies of warfare. IS produced a series of professional-grade videos titled “Salil al-Sawarim” (The Rattle of Swords), of which four episodes were made available in July 2012, August 2012, January 2014 and May 2014 respectively.(17)

After the Islamic State took control of Mosul in June 2014, it published a series of horrific videos that depicted brutal beheadings. The first of these, titled “Message to America”, showed an IS member beheading American hostage and journalist James Foley. On 2 September 2014, a second video, with the same title, showed the beheading of another hostage, American journalist Steven Sotloff.

On 14 September 2014, the organisation ran a third video, titled “Message to America’s Allies”, in which IS members were shown beheading British hostage David Haines, followed by yet another video on 3 October that showed the beheading of a second British hostage, Alan Henning, with threats to behead a third American hostage, Abdulrahman (Peter) Kassig. Kassig was subsequently beheaded as well in November 2014.

Various IS videos were extremely popular on YouTube, including “Kasr al-Hudud” (Smashing Borders,) uploaded on 29 June 2014, and Baghdadi’s address in Mosul on 5 July 2014. The organisation has also uploaded a series of videos under the title “Rasail Min Ard al-Malahim” (Messages from the Land of Epics), which documented the victories and operations of the organisation, with more than 50 episodes uploaded so far.

Another series of videos is titled “Fa Sharrid Bihim Min Khalfihim” (Scatter them from Behind). Part one covered the battle in which ar-Raqqah’s 93rd Brigade was captured 23 August 2014, and part two covered al-Tabaqah airport’s takeover on 7 September 2014. There is also a video called “Ala Minhaj an-Nubuwwah” (On the Path of the Prophet), uploaded on 28 July 2014.

The “Laheeb al-Harb” (The Flames of War) video, is one of IS’ most high-quality productions, and one of the most terrifying. It includes coverage of many of the IS’s battles, as well as a message to coalition countries. It was produced by al-Hayat Centre, which handles English-language production within the organisation’s media apparatus. It was uploaded 17 September 2014.(18)

Baytul Mal (Department of Finance)

The Islamic State is the wealthiest in the history of jihadi movements. Its wealth exceeds even that of al-Qaeda and its regional branches. Since the Zarqawi era, the organisation has successfully built a vast fundraising network with many and varied sources of financing. There has been an effective financing committee since the days of Monotheism and Jihad. It relies on a network of fundraising activists who collect funds from individual businesspeople and in mosques, especially in wealthy GCC states and Europe, in addition to collecting money within Iraq, and administering spoils gained from conquering new ground and issuing various taxes.

As the organisation’s power grew, culminating in the declaration of the Islamic State of Iraq, it announced its first cabinet during 2006, with several ministries tasked with controlling revenues from oil and other natural resources. In 2009, a second cabinet was announced, in which Yunus al-Hamdani was appointed minister of finance.

Today, al-Baghdadi oversees the management of Bayt al-Mal (literally “House of Wealth”) which is headed by Mowaffaq Mustafa al-Karmoosh. The Islamic State’s finances have increased considerably since Mosul’s June 2014 fall and as it gained control over vast swathes of territory in Iraq and Syria. Some studies estimate Daesh’s total assets at two billion US dollars, given that it has several income sources at its disposal, the most important of which are: (19)

-

Donations and grants: News organisations have reported that individual Gulf citizens are large donors to the group in Iraq and Syria. The Islamic State also enjoyed a windfall from wealthy Iraqis who inflated its coffers after the fall of Mosul.

-

Charity, donations and Zakah (alms): During 2011 and 2012, supporters used mosques and the media to urge Muslims to dedicate their Zakah and charity money to jihad and resistance in Syria. These funds quickly and easily found their way to Daesh, al-Nusra Front, and other radical Islamist groups.

-

Ransom revenues: The organisation created an entrepreneurship kidnapping foreign nationals, employees of international organisations, and Western journalists, and then negotiating millions of dollars in ransom money with their families and home countries.

-

Taking possession of resources and goods in conquered areas: Hospitals, shopping centres, restaurants, and power and water utilities in these areas provide millions of dollars in revenue every month.

-

Revenues from natural resources and mining: The organisation took possession of oil and gas resources in Iraq and Syria. There are more than eighty minor oil fields under its control, the products of which are sold either locally or internationally through traders. Revenues are estimated at two million dollars per month. The organisation also controls gold mines in Mosul.

-

Taxes and stipends: businesspeople, farmers, industrialists and the wealthy in IS-controlled areas are some of the most important sources of funds. The organisation also collects Jizyah (money collected in exchange for protection) from non-Muslims, as well as monthly taxes from local businesses, estimated at six million dollars per month.

-

Government funds: Daesh successfully took cash estimated at tens of millions of dollars from banks and government institutions after Mosul’s fall.

-

Agricultural revenues: Daesh controls large numbers of wheat and produce fields in Iraq and Syria, with as much as a third of Iraq’s wheat production at its disposal.

Military council

Given its militant nature, the military council is the Islamic State’s most important entity. The number of its members varies according to its power and influence. Historically, the number of members varied between nine and thirteen.(20) The name “military council” came about after IS’ minister of war, Numan Mansour al-Zaidi’s died in May 2011 (also known as Abu Sulaiman al-Nasser Ledeen Allah).

The military council’s commander is simultaneously one of Baghdadi’s deputies. Zarqawi used to hold both positions until Abu Hamzah al-Muhajir became minister of war in the days of the Islamic State in Iraq and continued while Abu Omar al-Baghdadi was emir. During Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi’s reign, Haji Bakr (formerly Samir Abed Mohammed al-Khlaifawi,) became military commander. After he was killed in Syria in January 2014, he was succeeded by Abu Abdul Rahman al-Bilawi (formerly Adnan Ismail al-Bilawi) who was killed in June 2014. The current head of the military council is Abu Muslim al-Turukmani (formerly Fadl al-Hayyali).

The military council consists of sector commanders, with each sector comprising three battalions of 300 to 350 fighters each. Each battalion is made up of several companies containing fifty to sixty fighters apiece. Within the council, there are general staff, special commandos, and suicide officers, as well as logistics forces, sniper forces, and ambush forces. Higher-ups include Abu Ahmed al-Alwani (also known as Walid Jassim) and Omar al-Shishani. The council handles all military aspects, including strategic planning, battle commands, attack planning, and oversight, supervision and correction of military commanders’ operations, as well as armament and spoils management.

Security Council

This is one of the Islamic State’s most important, and most dangerous, councils. It handles security and intelligence under the command of Abu Ali al-Anbari, a former intelligence officer with the Iraqi Army, who has a number of deputies and aides. The council runs the security affairs of the organisation and handles security detail for the caliph, including securing his residences, appointments and movements. It also follows up on the implementation of Baghdadi’s decisions and how seriously provincial governors take his orders. It monitors the operations of security commanders in provinces, sectors and cities, and oversees the implementation of judicial rulings and punishments, as well as the infiltration of rival organisations and protecting the IS from infiltration. It also controls special units, such as suicide bombers and undercover agents in coordination with the military council. The council has platoons in every province, which run the mail and coordinate communications among the organisation’s bodies across sectors. There are also special platoons that carry out political assassinations, kidnappings and money collections.

Administrative structure

The areas under the Islamic State’s control are divided into administrative units called “wilayat” (states or provinces) – the traditional name for such geographically-designated units within the Islamic empire, and each wilaya is governed by an appointed official called a “wali”, which is the historical term for a governor in the Muslim empire. Senior officials under the wali’s command are called “emirs” (or commanders) and they control their assigned sector. These include a military emir, a Shariah emir who heads the province’s Shariah establishment, and a security emir. The emir is the highest authority in his sector. Walis and their deputies oversee the emirs of sectors, who preside over the emirs of cities and their deputies.

There are sixteen administrative divisions under the control or influence of the organisation, half of which are in Iraq: Diyala; the southern provinces; Salahuddin; Anbar, Kirkuk, Nineveh, and governorates north of Baghdad. The other half is in Syria: Homs, Aleppo, al-Khair (officially Deir Ez-Zor,) al-Barakah (officially al-Hasakah,) al-Badiah (in the desert areas), ar-Raqqah, Hama and Damascus.(21)

Provinces are divided into sectors which include their respective cities and retain the names they had prior to Daesh’s invasion. For example, the Aleppo province is divided into two sectors: the Manbij sector, which includes the cities of Manbij, Jarabulus and Maskanah, and al-Bab sector, which includes the cities of al-Bab and Dayr Hafir.

Current prominent leaders

Generally speaking, there are a number of leading figures within the Islamic State today. The supreme commander is the caliph, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. His deputy, Fadhel Ahmed Abdullah al-Hiyali (also known as Abu Motaz), coordinates Iraqi provinces’ affairs of provinces. Abu Muslim al-Turukmani al-Afri, who resides in Nineveh, is the president of the military council. The Wali of Anbar, Adnan Latif Hameed al-Suwaidawi (also known as Abu Muhannad Al-Sweidawi or Abu Abdul Salam) is a member of the military council.

In the southern and mid-Euphrates province, the Wali is Ahmed Mehsen Khalaf Al-Juhaishi (also known as Abu Fatimah). Karmoosh (also known as Abu Salah) is in charge of finance, Mohammed Hameed al-Dulaimi (also known as Abu Hajar al-Assafi) is the mail’s general coordinator, and Awf Abdul Rahman al-Afri (also known as Abu Suja) coordinates patronages and widows, martyrs families and prisoners affairs.

Of the administrative figures, there is Faris Riad al-Nuaimi (also known as Abu Shaymaa), special mail coordinator in charge of inventory. Tai is in charge of bombmaking and vehicle rigging. Shoukat Hazim Kallash al-Farahat (also known as Abu Abdulqader) is the administrator general.

The man who runs bunking facilities for Arab recruits and handles transportation of suicide bombers is Abdullah Ahmed al-Mashhadani (also known as Abu Qassim). Bashar Ismail al-Hamdani (also known as Abu Mohammed) is responsible for prison facilities, and Abdulwahid Khudair Ahmed (also known as Abu Louai or Abu Ali) is the chief security coordinator.

In Kirkuk, the Wali is Abu Fatimah. Rudwan Talib Hussein Ismail al-Hamduni (also known as Abu Jirnas) is the so-called Border Province’s wali; Wisam Abed Zaid al-Zubaidi (also known as Abu Nabil) is the wali of Saladin, and the wali of Baghdad is Ahmed Abdulqader al-Jazzaa (also known as Abu Maysarah and Abu Abdulhamid).(22)

Conclusion

Clearly, Daesh’s structure is growing in sophistication. What began as a rather simple amalgamation of clusters of local Islamic jihadi groups in the first few months of their existence developed into more clearly defined institutions and bodies by the time Monotheism and Jihad came into being, with further development as it joined al-Qaeda and declared al-Qaeda’s Base in Mesopotamia.

After Zarqawi’s killing, the organisation adopted a more institutionalised formula that attempted to mimic the past in Islamic heritage, manifested by the formation of ministries and the appointment of governors to areas under IS control, in an apparent attempt to move away from a mere organisation to fully fledged statehood.

The real metamorphosis, however, occurred later under the reign of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. Various bodies were given specific frameworks and allocated particular, precise tasks that blended the normal functions of a modern state on the one hand, with the more mysterious, complicated nature of the organisation on the other. This created a unique structure that melded the aspects of a modern state with the labyrinthine intricacies of a secret organisation.

Development was not confined to the institutional and functional aspects of the organisation. It was accompanied by sweeping restructuring of leadership and the empowerment of professional local leaderships, especially on the military, security and economic fronts. Several figures had a significant hand in IS reaching this level of professionalism, such as Haji Bakr, Abu Abdul Rahman al-Bilawi, Abu Ali al-Anbari and Abu Ayman al-Iraqi.

The organisation revealed a unique ability to distribute tasks among its local members and foreigners (Arab and Muslim recruits). Despite this “administrative double standard” and the apparent dominance of Iraqi nationals within key sections of the organisation’s leadership in recent times, it managed to assimilate foreign recruits by assigning specific roles and tasks to them, thus blending the nationalised nature of the Islamic State and regional and international aspects of the Islamic caliphate. This might explain one of the most important reasons that they declared a caliphate: to maintain internal solidarity of the organisation as well as maintain its ability to contain its membership’s heterogenic nature, including Iraqis, Syrians, Arabs, Asians and even Europeans. Its religion-based framework, akin to the Abbasid caliphate in Baghdad, enabled this heterogenic nature. It might also explain why Baghdadi wore black in the famous video of his address in Mosul, since black is historically associated with the Abbasid caliphate.

The number of recruits multiplied after Mosul’s fall and the declaration of the caliphate, which is natural considering the Islamic State’s newly-gained power and influence. It is a well-known fact that whenever Daesh conquers new land, it encourages the locals to pledge allegiance to the caliph through intensified mobilisation and propaganda campaigns. It deeply infiltrates local education, media and judicial institutions, effectively forcing the locals to buy into it, either from fear of cruel and violent retaliation or in hopes of somehow benefitting from joining what they cannot beat.

Despite Daesh’s sophistication manifested so far in its organisational structure, efficient recruitment, effective propaganda, and maintaining solidarity, this does not mean that it doesn’t face grave challenges. The rapid expansion of operations within IS’ area of influence hides real threats to its integrity and further geographical expansion, particularly if it suffers damaging military strikes and counterattacks, or in the event the US is successful in besieging it economically and geographically, thus draining it of power and subsequently chipping away at its recently gained power.

_________________________________

Hassan Abu Haniyeh is a researcher specialising in Jihadi groups.

Endnotes

1. Mohammad Aburumman and Hassan Abu Haniyeh, Jihadi Salafism in Jordan after the death of Zarqawi: Identity Approach, Leadership Crisis, Unclear Vision, (Amman: Friedrich Ebert Foundation, 2009), 12-29.

2. Abu Abdullah al-Muhajir, whose real name was (Sheikh) Abdul Rahman al-Ali, an Egyptian national, was regarded highly among Jihadis all over the world. He got his Islamic education in Pakistan, and was very close to Zarqawi. After graduating from the Islamic University in Islamabad, he moved to Afghanistan, where he established a scholastic dawah center at the Khalden training camp. He taught at the Arabic Language Centre in Kandahar, and then at mujahidin camps in Kabul, and oversaw indoctrination at Zarqawi’s camp in Herat. He was poised to take charge of al-Qaeda’s spiritual guidance committee. According to Maysara al-Gharib, al-Qaeda’s propagandist in Iraq, al-Muhajir had been detained in Iran and released months after the revolution in that country, after which he returned to Egypt. He is considered the mufti of Zarqawi’s group. See also: http://www.sunnti.com/vb/showthread.php?t=15452.

3. Abu Anas al-Shami, Diary of a Mujahid, (Muntada Shabakit Asafinat al-Islamiyah), www.al-saf.net.

4. Abu Anas al-Shami is Omar Yousef Jumuah, a Jordanian of Palestinian descent born in 1969. He settled in Jordan after the second Gulf War, and went to Bosnia as a teacher to participate in Jihad there. In Jordan, he was an Imam and head of the Imam Bukhari Center run by al-Kitab wal Sunnah.

5. Declaration at this link: http://www.tawhed.ws/r?i=dwww5009.

6. See declaration of the pact, in which a few veiled men, said to be tribal leaders and members of the council, appeared to pledge to govern by Shariah and give allegiance to the mujahideen in Iraq, at: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=60mgEeNc7Z8.

7. See: “Statement of ISI’s Founding”, September 2009, at https://nokbah.com/~w3/?p=536.

8. The Complete Speeches of the Leaders of the Islamic State of Iraq, 1st edition, 19 April 2007.

9. Statement of ISI’s founding, 2009.

10. See statement at: http://www.muslm.org/vb/archive/index.php/t-388724.html.

11. These numbers are based on the author’s interviews with anonymous sources close to the group.

12. For its structure, IS uses Islamic literature on statehood, governance and Caliphate for reference, especially books about imperial rule. After IS was declared, Othman bin Abdul Rahman al-Tamimi, the organisation’s spiritual officer, issued a book titled Declaration of the Birth of the State of Islam, which is based on traditional Islamic literature that teaches the incumbency of a Muslim Caliphate.

13. Haytham Manna, ISIS’s Caliphate, From the Phantoms of Illusion to Lakes of Blood, Part I, (Geneva: Scandinavian Institute for Human Rights, 2014), at: http://sihr.net/wp-content/uploads/2014/07/DAEESH-first-part1.pdf.

14. Suhaib Anjarini, “Islamic State: from Baghdadi the Founder to Baghdadi the Caliph”, al-Akhbar, 10 July 2014, http://www.al-akhbar.com/node/210299.

15. Hisham al-Hashimi, “ISIS structure: 18 deadliest terrorists who threaten Iraq’s stability”, al-Mada, 15 June 2014, http://almadapaper.net/ar/printnews.aspx?NewsID=466428.

16. Speech by Abu Mohammed al-Adnani, titled “This is God’s Promise”, al-Furqan media production establishment, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=b1qkBXKvs_A.

17. All four episodes can be found here: http://ansarkhelafa.weebly.com/15871604158716041577-1589160416101604-1575160415891608157515851605.html.

18. All videos published by the Islamic State can be found here: http://dawla-is.appspot.com/.

19. Ahmed Mohammed Abu Zaid, From Donations to Oil: How ISIS became the richest terrorist organisation in the world, The Regional Center for Strategic Studies, 10 September 2014, http://www.rcssmideast.org/Article/2668/%D9%83%D9%8A%D9%81-%D8%AA%D8%AD%D9%88%D9%84-%D8%AF%D8%A7%D8%B9%D8%B4-%D8%A5%D9%84%D9%89-%D8%A3%D8%BA%D9%86%D9%89-%D8%AA%D9%86%D8%B8%D9%8A%D9%85-%D8%A5%D8%B1%D9%87%D8%A7%D8%A8%D9%8A-%D9%81%D9%8A-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B9%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%85-#.VFguPfmUckY.

20. Hisham al-Hashimi, “ISIS’ Structure: 18 Deadliest Terrorists Threatening Iraq’s Stability”, al-Mada, 15 June 2014, http://almadapaper.net/ar/printnews.aspx?NewsID=466428.

21. Suhaib Anjarini, 2014.

22. See the translated Telegraph report, 11 July 2014, http://www.alarabiya.net/ar/arab-and-world/iraq/2014/07/10/%D8%AE%D9%84%D9%8A%D9%81%D8%A9-%D8%AF%D8%A7%D8%B9%D8%B4-%D9%88%D8%A3%D8%B9%D8%B6%D8%A7%D8%A1-%D8%AD%D9%83%D9%88%D9%85%D8%AA%D9%87.html.

| Back To Main Page |