At the outset of its establishment in June 2014, the Islamic State in Syria and Iraq (ISIS) seemed more committed to organizing a state and uniting the Muslim world under one banner, the Caliphate, than conducting terrorist attacks abroad. Soon it became the most powerful, wealthiest, and best-equipped extremist group ever seen. However, the rate of its decline has raised many questions: has the organization and its ideology become a lost cause? Is it going to reshape itself, find new fronts, and change into something else, more threatening, in Syria, Iraq, and other regions such as in North Africa (i.e. Libya) and the Sahel (i.e. Mali) where chaos is still prevailing in these regions?

In his first State of the Union address in January 2018, President Donald Trump declared ISIS militarily defeated, and reminded the Congress of his 2017 pledge to work with America’s allies to extinguish ISIS from the face of the Earth. He asserted that “one year later, I'm proud to report that the coalition to defeat ISIS has liberated very close to 100 percent of the territory just recently held by these killers in Iraq and Syria"(1). When Trump was elected president November 8, 2016, the United States-led-coalition had already taken more than 13,000 square miles from the group. However, when he began his presidency in January 2017, ISIS controlled around 23,300 square miles of territory across Iraq and Syria. Once in office, Trump accelerated the pace of military operations by giving the American commanders more authority to strike and make battlefield decisions.

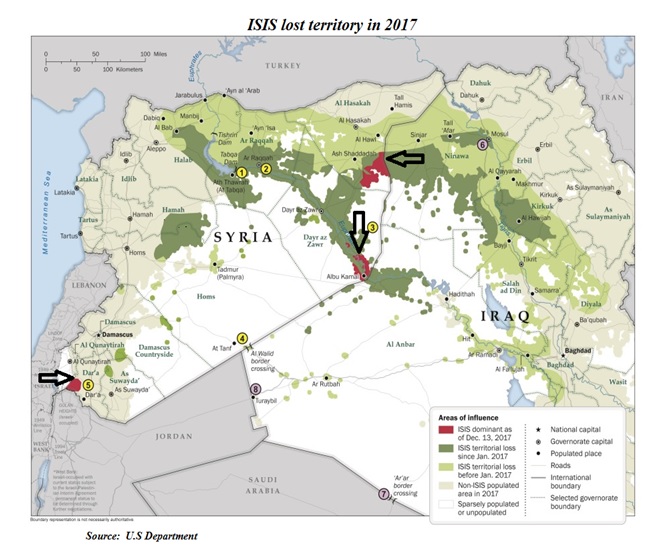

As a result, ISIS territory dramatically shrunk to 9300 square miles, when Raaqa was liberated in October 2017(2). At the start of 2018, ISIS is barely holding a small portion in the Jazeera desert in Iraq’s Anbar province, and a few towns along the Euphrates River banks in Syria roughly no more than 1900 square miles or 4% of its original territory(3).

|

| [US State Department] |

Thus, ISIS lost around 21,400 square miles or 96% of the territory, mirroring almost 100 percent territorial lost that President Trump mentioned in his speech. The following map from the U.S. State Department illustrates ISIS’s territorial losses in 2017.

Source : US State Department

Just by looking at the map, the losses in 2017 are significant compared to previous years(4). But even as the group is being decisively defeated on the battlefield after losing key territories including its de-facto capital Raaqa in October 2017, the organization is far from being uprooted; and it is premature to claim ISIS has been extinguished from the face of the Earth. The organization is simply going underground and it is a part of a cyclical process of this group; it is not linear. The organization does not have a start and end date; however, its power has shifted between controlling territory and losing territory. In other words, ISIS switches from governing mode to insurgency mode. Some observers like Stephen Walt points out that “we should be wary of a premature “Mission Accomplished” moment and be judicious in drawing lessons from an outcome that otherwise merits celebration.”(5)

This transformation means there is no direct link between the battlefield losses in Syria and Iraq and its capacity to continue inspiring new recruits, conducting attacks, and cultivating divisions among the population. In early 2018, some 3,000 ISIS fighters and 7,000 loyalists of ISIS, including women and children have remained in Iraq and Syria. About 10,000 fighters are still committed despite international operations to annihilate the group(6). A fraction of those fighters is more than enough to wage a new insurgency in the region. Therefore, battlefield victories against ISIS are not enough, and are not sufficient to alleviate, alone, its lingering threats.

The rise of ISIS has changed the geopolitical reality in the Middle East and imposed one of the most significant territorial shift since the Sykes-Picot Agreement was implemented in the aftermath World War I. However, the decline of the militant group has created an open-ended geopolitical dilemma, and triggered a competition for control between several stakeholders in the region. Accordingly, the turbulent situation in Syria may led to new direct confrontations: Iran versus Israel over the Golan Height, Turkey versus the Kurds in Afrin, and the United States versus the Syrian regime, as was the case of the two air attacks in April 2017 and April 2018. The post-ISIS Middle East will most likely determine the parameters for the future of the conflict over the next decade.

Jason Burke author of “The New Threat: The Past, Present and Future of Islamic Militancy” argues that “If the defeat of ISIS did not come easily, three inherent weaknesses of its project always made it likely in the long term. First, ISIS needed continual conquest to succeed: victory was a clear sign that the group was doing God’s work. Expansion also meant new recruits to replace combat casualties, arms and ammunition to acquire, archaeological treasures to sell, property to loot, food to distribute and new communities and resources, such as oil wells and refineries, to exploit.”(7)

In theory, the current geopolitical situation does not reflect ISIS's aspirations, because almost all parties involved in the conflict in Syria and Iraq are committed to fight the organization. But in practice, this state of affairs may make the reemergence of ISIS inevitable, since the drivers that produced ISIS loom even larger today than when it first emerged. The Islamic State Jihadists claimed a suicide attack at Libya’s Electoral Commission building in Tripoli May 2, killing at least a dozen people including two Libyan policemen. The collapse of ISIS has created a terrorist diaspora with the potential to carry out sophisticated attacks in the West and radicalize other Muslims in the Arab world(8).

Moreover, the organization's ideology remains widespread. U.S. Army Lt. Gen Paul Funk asserted that the group’s repressive ideology continues; “the conditions remain present for ISIS to return, and only through coalition and international efforts can the defeat become permanent"(9). Ideologies often outlast those who created and spread them, even if the organization's most inspiring leaders are killed. ISIS spokesperson Abu Mohammed al-Adnani said, before he was killed, that potential setbacks in Mosul and Raqqa would not spell the group's end; "the fight is losing the will and the desire to fight"(10). As much as the statement is frightening, it indicates that extremist ideology is still evolving. The challenge is to counter this ideology, rather than only focusing on military and security approaches.

|

| [STATISTA] |

Although these efforts have borne fruit and are to be praised, the experience with Al-Qaida in Afghanistan showed that military and security measures, adopted as short and middle-term strategies, have proved to be limited. The same reflection applies to al-Qaeda, which survived in Iraq, after its defeat by the US-led campaign and the so-called ‘Surge’ in 2007. Al-Qaeda retreated to the deserts of western Iraq, disrupted politics, fostered sectarianism, and waited for a point of reentry in 2011, the start of the civil war in Syria. ISIS may follow a similar strategy to gain momentum again. The plan is to regroup, maintain their relevance and through a mix of international and local terrorism attacks, they will try to keep their cause alive. ISIS now has two countries where it can exploit cleavages.

Terrorism strategists have suggested several counter-ISIS strategies where more attention focuses on the military defeat rather than the ideological eradication. They tend to address one aspect of a complex issue rather than dealing with a toxic ideology that can affect an entire generation. These strategies can be categorized into three plans of action: political settlement, military campaign, and containment.

A Political Settlement

In her meticulous analysis "The Islamic State's Strategy Lasting and Expanding", Lina Khatib suggested her strategy framework to counter ISIS by emphasized a political settlement in Syria and Iraq as the best strategy(11). It consists of adopting comprehensive measures to win the trust of local Sunni populations in order to reach a political settlement while building domestic capabilities to defeat the group militarily. Therefore, it is unrealistic to expect the eradication of ISIS first and then to deal with the political transition in Syria where Assad has apparently no future in the final process. However, a compromise agreement without Assad is impossible, especially after the latest military achievements and his vows to retake total control of Syria. Additionally, Assad regime did not show any willingness to make concessions that could attract the Sunni community. A political settlement, however, in Iraq is possible if the Iraqi government takes positive steps to end the sectarian policies adopted by the Maliki government (2006-2014).

A Military Campaign

Other analysts have advocated the use of force to eradicate ISIS. In his study "What happens when ISIS goes underground?", Daniel Byman at the Brookings maintains that the United States should not relax its pressure, as ISIS prepares to go underground, and should double its efforts with a particular focus on a sustainable coalition of local allies in Iraq and Syria.(12) Such military pressure may represent the best strategy to defeat the caliphate since it undermines its cause in the eyes of its supporters by showcasing that ISIS is no longer capable of achieving its declared objectives of "lasting and expanding". However, a military victory will be neither enough to curtail the ideological appeal of the group nor will end the insurgency. Due to the lack of domestic capabilities and strong allies who can prevent its reemergence, anti-ISIS groups are competing over power and influence, exacerbating the situation even further in the region.

A Containment Strategy

Military containment was a necessary antidote to ISIS’s early successes and was adopted as pragmatic way to limit its territorial expansion. This strategy rejects any new occupation, by sending troops to the region, which may trigger the same kind of resistance during the American invasion of Iraq in 2003. Militant groups such as ISIS have exploited the situation and capitalized on anti-American sentiment. As a manifestation of this containment policy, Obama's strategy “degrade and destroy” was ineffective in containing ISIS since it struggled with the ideological threat more than the military maneuvering. More importantly, containment does not offer an ideological framework to counter and prevent the militant group from regaining momentum in the future. Yet, with the group is going underground, there is need to look beyond containment.

Barry R. Posen is the Ford International Professor of Political Science at MIT, in his analysis "Contain ISIS" suggested more restrained strategy based on "Containment"(13). He concluded that containment is a tougher sell, because it requires patience and resilience; however, it does not promise a quick and easy victory. The need to address the conditions conducive to the spread of terrorism is crucial. However, solutions must transcend the use of military force or containment to defeat the ideology that fuels extremists.

An ideological defeat is a much tougher task because anti-extremism campaigns have usually been successful only after decades of tackling the root causes of those radical ideologies. Historical evidence showcases that it can take up to three generations before toxic ideologies can be uprooted from societies. Winning the battle for minds over ISIS is only possible if the battle engages the current generation of extremists and other future generations. It requires a large-scale collaboration between like-minded individuals, a new awareness campaign that matches the degree of the ideological extremism campaign and long-term commitment towards the Syrian and Iraqi people. Thus, the group's defeat cannot be accomplished unless there is a long term strategy—a clear roadmap that leads to an ideological defeat.

One can argue for objectives that need to be fulfilled to ensure an ideological defeat over the Islamic State within the framework of effectively disrupting, dismantling, and neutralizing ISIS in post-ISIS Syria and Iraq.

The Security Imperative

Every strategy that aims to defeat ISIS ideologically must begin with establishing security in the previously-ISIS controlled territories in Syria and Iraq. This objective implies deploying adequate forces that are capable of protecting these territories and providing security for the local population. This security apparatus needs military assistance, training, and equipment from the international community.

After World War II, it took more than a decade to establish security in Germany before setting up programs aimed at countering the Nazism ideology and another decade to have an effect(14). However, in Afghanistan, countering ideologies have not taken place because of the counter-insurgency operations that continue sixteen years after the U.S. military intervention. In contrast, governing more effectively than ISIS requires empowering local councils that reflect the region's ethnic groupings. It is important to note that stable, sustainable and long-term governance is the best buffer between the local population and extremism. In help adopt a broader strategy of counterterrorism, it is paramount to recognize the strong correlation between extremist terrorist groups and civil wars. Pursuing the end of these wars is necessary to help lead to an ideological defeat of radical groups. Programs for conflict resolution and sustained diplomacy are vital to mitigate the effects of the Syrian civil war while implementing a wider comprehensive roadmap to end the conflict.

The De-radicalization Potential

The second priority is launching programs that involve treatment and rehabilitation of those who have been radicalized with the aim of re-educating and integrating them in their societies. The radicalization tendency, which leads to violence rarely takes the form of a sudden or abrupt change. It is complex social change that operates on different levels. Developing a program of rehabilitation and reintegration tailored to the local context would not succeed without addressing the problem at its root. Enabling such programs is generally a part of networks or coordination teams involving social workers, teachers, psychologists, and religious scholars. This meticulous process requires the implementation of a multi-agency approach to provide early intervention support for individuals or groups who are at risk of radicalization.

In order to deconstruct ISIS ideology, one needs to consider multiple factors—personal and collective, social and psychological that shape the path of radicalization. ISIS has two categories of members: ‘instigators’ and ‘perpetrators’. The first category ‘instigators’ usually hold key positions in the organization and they have sophisticated ability to inspire new recruits. They are well educated and most of them hail from rich families like Osama ben Laden or Abu Bakr Baghdadi (PhD in Sharia studies). Extremist ideology is entrenched in their beliefs. It is almost impossible to change their convictions because they are categorically convinced that their system of beliefs is absolute and exclusive.

Such individuals reject any competing explanations or alternative views. The only way to face them is to solve the problem of ‘perpetrators’ while neutralizing and isolating them from other members especially during the de-radicalization process. However, this group represents the majority in the organization who are easily manipulated. Most of them suffer from marginalization, unemployment, and low self-esteem in their original countries. At this point, giving them more economic opportunities and helping them is the best step to effective, permanent rehabilitation and reintegration of this group.

Perhaps the most successful experience is a program experimented by the City of Aarhus in Denmark. It provides additional tools needed to address the full-life cycle of radicalization to violence: from prevention, to intervention, to rehabilitation and reintegration(15). The local Aarhus government offers its citizens, who have returned from Syria and Iraq, “help with finding an apartment, meeting with a psychiatrist or a mentor, or whatever they need to fully integrate back into society.”

Another example from a different context, the Algerian civil war could be another case study as a successful experience for Arab countries. Algeria’s de-radicalization program guaranteed amnesty to thousands of Algerian extremists and allowed them return to their communities. The program provided a platform to express remorse, repent, and renege violent ideology for all fighters and prisoners convicted of terrorism, while meeting with religious scholars in order to reshape their interpretation and thoughts of Islam. As a result, only an estimated 170 fighters from Algeria joined ISIS, while more than 3,000 Tunisian and 1,500 Moroccan citizens joined the organization(16).

|

| [Statista] |

The Basic Human Needs Reform

Addressing the longstanding grievances that led the population to accept ISIS is the third priority to defeat the organization. Ideology was not the primary driver why young Arabs and foreigners chose to join ISIS. Many Sunni communities in Syria and Iraq decided that living under ISIS was better than being a victim of exclusion within the majority-minority agendas of politics. Furthermore, the gloomy socio-economic horizon and lack of opportunities still serve as favorable conditions, in a fertile ground, for a new insurgency in both countries. Ultimately, ISIS has benefited from two powerful dynamics: socio-economic problems that marginalized poor individuals, and sectarian policies that deprived other sects from key jobs and climbing social ladders in Iraq and Syria.

Lack of gratifying these basic human needs allows extremism and violence to thrive as a conduit of resistance and sometime vengeance. Accordingly, the elimination of ISIS's ideological appeal requires cutting these two main lifelines. Autonomy or federalism could be the most viable option to diminish the effect of sectarianism in the region, allay citizens' fears, and restore trust in government. However, maintaining a central government will guarantee protection to minorities and preserve the geopolitical balance in the region.

The exclusion factor that has derived from poverty, political alienation, and economic hopelessness, has played a role in recruiting young people from the Middle East and North Africa by ISIS. For instance, Tunisia is the leading nation in exporting jihadists, with more than 3000 Tunisians. The majority of these fighters hailed from the southern region, which suffers from marginalization and high unemployment(17).

Countering the Discourse

Propaganda has served as a significant driver of radicalization. Any strategic endeavor to counter ISIS's propaganda requires understanding the construction and dissemination of the radical discourse and socio-cultural nuances. Since 2011, ISIS has succeeded in recruiting an estimated 20,000 fighters through its propaganda machine, which includes social media(18). One of the reasons for this communication success is that many ISIS fighters have a criminal history and a superficial knowledge of Islam. By contrast, ISIS has offered them everything a street gang does: status, power, financial opportunities, love connections and the possibility of redemption from previous sins. This is a very attractive offer for former criminals(19). Counter-efforts, meanwhile, have been largely ineffective in scope and funding. Therefore, countering this propaganda machine should include:

First, to delete content, including profiles, pages, or groups related to terrorist organizations. This effort has paid off, especially after the videos of journalist James Foley's beheading in August 2014 spread on social media, where Twitter took an aggressive approach and deleted all ISIS-related content(20). Twitter’s reaction has kept the size of the ISIS network relatively constrained. Furthermore, social media represents a gold mine for Intelligence services to determine supporters and potential recruits, identify individuals not previously on the government's radar, and helps track sleeper cells and contacts(21).

Second, to expose and publicize the group's atrocities against Sunnis in the region. For example in an American government produced video named “Run, do not walk, to ISIS Land” — viewed more than 844,000 times on YouTube — ISIS promised new arrivals to learn “useful new skills” such as “crucifying and executing Muslims.” Through this video, the U.S. State Department used ISIS’s own horrific footage to launch a campaign aimed at countering its propaganda and containing the spread of extremist ideology(22).

Third, to disseminate moderate arguments from religious scholars who have contested ISIS’s interpretation of Islam and rejected its vision of Jihad. Recent studies conducted in eight countries have indicated that 90% of people feel that mainstream Muslim voices are most effective at rebutting extremist narratives(23). However, these arguments need to reach the right audience: ISIS’s potential recruits. In doing so, the organization will likely be isolated and neutralized from enlisting new members in Syria, Iraq and elsewhere.

The Re-education Promise

The fifth priority should be a new point of entry into education. It involves creating educational programs that inspire youth leaders in Syria and Iraq and beyond with an enlightened would view and a sense of coexistence. These programs would aim at contesting various aspects of the extremist ideology and provide the young generation with moderate understanding of issues of religiosity, culture, and identity. These re-education programs should be incorporated in countering-extremism policies as a preventive measure that can produce more moderate local leaders able to critically analyze extremist views and curb the trend of radicalization(24). Unless we reach the target audience before the recruitment stage and show them, at an early age, the ills of radicalization, fighting terrorism will be "forever". Richard Clarke, a former counterterrorism official at the White House has concluded that “unless you beat them at the recruitment game, then you will constantly and forever be fighting counterterrorism"(25).

Conclusion

Western hegemonic policies in the Middle East and North Africa has exacerbated terrorism. They have played a significant role in fueling narratives of Muslim victimization and resentment, which led to the current predicament. From invading Iraq to undermining and ousting governments in the region to supporting authoritarian regimes that oppressed their people, the reaction has sometimes been channeled into extremist mobilization. These policies provided a pretext for those extremists to conduct attacks in the name of protecting the Muslim World.

Although most ISIS's victims are Muslims accounting for 90% of all terrorism fatalities, according to the US National Counterterrorism Center, there is no justification for killing innocent people, whether they are Muslims or non-Muslims(26). However, radical groups are using Jihad as a tool to further a hidden political agenda that serves no-one interest but leads to chaos. As British former Prime Minister Tony Blair put it, "Without the Iraq war, there would be no Islamic State."(27)

No one strategy or expert view can guarantee that some individuals will not embrace radical ideologies. However, analysts and policy-makers should reflect: why are radical groups doing what they are doing? What are their motivations? Why are they justifying their actions? The narrative in the West is dominantly shaped by a short-sighted interpretation of the root causes of terrorism. Former FBI special agent Ali H. Soufan once said “Achilles heel of America’s policy against terrorism is its failure to counter the narratives that inspire individuals to become extremists and terrorists.”(28)

(1) Trump state of the union address, January 30, 2018. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=J4FmQtOPbF4, For more information you can see also: https://www.cnn.com/2018/01/30/politics/donald-trump-sotu-international-lines-intl/index.html

(2) Lina Qiu, "Can Trump Claim Credit for a Waning Islamic State?", The New York Times, October 17, 2017. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/17/us/politics/trump-islamic-state-raqqa-fact-check.html

(3) Jamie McIntyre, "Here's how much ground ISIS has lost since Trump took over", Washington Examiner, December 23, 2017. Available at: https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/heres-how-much-ground-isis-has-lost-since-trump-took-over

(4) The U.S State of Departement, December 21,2017, State Information Service.Available at: https://content.govdelivery.com/attachments/USSTATEBPA/2017/12/21/file_attachments/933854/map.jpg

(5) Stephen Walt, “What the End of ISIS Means”, Foreign Policy, October 23, 2017 http://foreignpolicy.com/2017/10/23/what-the-end-of-isis-means/

(6) Saphora Smith and Michele Neubert "ISIS will remain a threat in 2018, experts warn", NBC news, Dec.27.2017. Available at: https://www.nbcnews.com/storyline/isis-terror/isis-will-remain-threat-2…, check also: Hassan Hassan, coauthor of the book "ISIS: Inside the Army of Terror," March 29, 2016. For more information you can see also: Ellen Mitchell ,Experts warn ISIS still has up to 10,000 loyalists in Syria, Iraq: report. Available at: http://thehill.com/policy/defense/370150-experts-warn-isis-still-has-up-to-10000-loyalists-in-syria-iraq-report

(7) Jason Burke, “Rise and fall of Isis: its dream of a caliphate is over, so what now?”, The Guardian, October 17, 2017 https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/oct/21/isis-caliphate-islamic-state-raqqa-iraq-islamist

(8) Testimony of Colin Clarke 'The RAND Corporation' Before the Committee on Homeland Security Task Force on Denying Terrorists Entry into the United States United States House of Representatives "The Terrorist Diaspora: After the Fall of the Caliphate", July 13, 2017. Available at: https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/testimonies/CT400/CT480/RAND_CT480.pdf

(9) John Bowden "US general: ISIS's 'repressive ideology' endures despite lost territory", The Hill, January 01,2018. Available at: http://thehill.com/policy/defense/367002-us-general-isiss-repressive-ideology-endures-despite-lossesJohn

(10) Tim Lister, “Where does ISIS go after Mosul?”, CNN, July 10, 2017 https://edition.cnn.com/2017/07/10/middleeast/isis-after-mosul/index.html

(11) Lina Khatib, "The Islamic State’s Strategy Lasting and Expanding", June 2015 http://carnegieendowment.org/files/islamic_state_strategy.pdf

(12) Daniel L. Byman, "What happens when ISIS goes underground?", Brookings Institution, January18,2018. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/markaz/2018/01/18/what-happens-when-isis-goes-underground/

(13) Barry R. Posen "Contain ISIS" The Atlantic, November 20, 2015. https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2015/11/isis-syria-iraq-containment/416799/

(14) Colonel R. J. Boyd British Army "The Battle for Minds. Defeating Toxic Ideologies in the 21st Century", 2013, United States Army War College. http://www.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a589036.pdf

(15) Eric Rosand, "It’s time to use local assets in the global campaign against ISIS", Monday, March 20, 2017, Brookings Institution. Available at: https://www.brookings.edu/blog/order-from-chaos/2017/03/20/its-time-to-use-local-assets-in-the-global-campaign-against-isis/

(16) Dalia Ghanem Yazbeck, "Why Algeria Isn’t Exporting Jihadists", The Carnegie Endowment For International Peace, August 11, 2015. Available at: http://carnegie-mec.org/2015/08/11/why-algeria-isn-t-exporting-jihadists-pub-60954

(17) Anouar Boukhars, "The Potential Jihadi Windfall From the Militarization of Tunisia’s Border Region With Libya", The Carnegie Endowment For International Peace, January 26, 2018. http://carnegieendowment.org/2018/01/26/potential-jihadi-windfall-from-militarization-of-tunisia-s-border-region-with-libya-pub-75365

(18) Alberto M. Fernandez, "Here to stay and growing: Combating ISIS propaganda networks" Brookings Institution, Wednesday, October 21, 2015. Available at: https://www.brookings.edu/research/here-to-stay-and-growing-combating-isis-propaganda-networks/

(19) Jason Burke, "Rise and fall of Isis: its dream of a caliphate is over, so what now?", The Guardian, October 21, 2017. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/oct/21/isis-caliphate-islamic-state-raqqa-iraq-islamist

(20) J.M. Berger, "The Evolution of Terrorist Propaganda: The Paris Attack and Social Media", Brookings Institution, Tuesday, January 27, 2015. Available at: https://www.brookings.edu/testimonies/the-evolution-of-terrorist-propaganda-the-paris-attack-and-social-media/

(21) Daniel Byman and Jeremy Shapiro , "We shouldn’t stop terrorists from tweeting", The Washington Post, October 9, 2014. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/we-shouldnt-stop-terrorists-from-tweeting/2014/10/09/106939b6-4d9f-11e4-8c24-487e92bc997b_story.html

(22) Greg Miller and Scott Higham, "In a propaganda war against ISIS, the U.S. tried to play by the enemy’s rules", The Washington Post, May 8, 2015. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/in-a-propaganda-war-us-tried-to-play-by-the-enemys-rules/2015/05/08/6eb6b732-e52f-11e4-81ea-0649268f729e_story.html

(23) Milo Comerford and Rachel Bryson, " Struggle Over Scripture Charting the Rift Between Islamist Extremism and Mainstream Islam", Tony Blair Institute for Global Change, December 2017. Available at: https://institute.global/sites/default/files/inline-files/TBI_Struggle-over-Scripture_0.pdf

(24) Ratna Ghosh, W.Y. Alice Chan, Ashley Manuel and Maihemuti Dilimulati, "Can education counter violent religious extremism?", Canadian Foreign Policy Journal, May 25, 2016. Available at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/11926422.2016.1165713

(25) Sam Stein and Jessica Schulberg, " We Aren't Going To Eradicate ISIS, Now Or Anytime Soon" The Huffington Post, Dec 19, 2016. Available at: https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/terrorism-experts-isis-paris_us_564b8f25e4b08cda348b364c

(26) National Counterterrorism Center: Annex of Statistical Information Country "Reports on Terrorism 2011", July 31, 2012. Available at: https://www.state.gov/j/ct/rls/crt/2011/195555.htm

(27) Martin Chulov, "Tony Blair is right: without the Iraq war there would be no Islamic State", The Guardian, Oct 25, 2015. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/oct/25/tony-blair-is-right-without-the-iraq-war-there-would-be-no-isis

(28) Debasish Mitra, "Flawed Policies Have Helped Terrorism Thrive", The Soufan Group, June 11, 2013. Available at: http://www.soufangroup.com/flawed-policies-have-helped-terrorism-thrive/