French troops aboard armoured vehicles are greeted by the population as they arrive in Timbuktu in this January 28, 2013. (REUTERS/Arnaud Roine/ECPAD/Handout)

Before 2012, many observers considered Mali and its President Amadou Toumani Touré a success story for the “third wave” of democracy. After leading a coup in 1991 and overseeing a democratic transition, Touré gave up power in 1992 upon the election of President Alpha Oumar Konaré. After Konaré’s tenure, Touré returned to politics, winning elections in 2002 and again in 2007 as a civilian president. As Malian politicians prepared for another presidential election scheduled for April 2012, Touré seemed poised to freely relinquish power once more.

Three months before the April 2012 elections, Tuareg separatists in north Mali under the National Movement for the Liberation of the Azawad (MNLA, where “Azawad” refers to the northern regions of Kidal, Gao, and Timbuktu), declared a rebellion against the central government. The regime's soldiers suffered defeats and seemed too ill-equipped to withstand rebel assaults. Soldiers’ discontent with the regime, which they blamed for their losses, erupted into protests, mutiny, and ultimately a coup against Touré on 22 March 2012. The coup created a power vacuum that enabled Tuareg rebels in the north backed by a patchwork of Islamist forces to take control of nearly two thirds of the country. These disparate Islamist forces included Ansar Dine (“Defenders of the Faith”), Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), and Jama’a al Tawhid wa al Jihad fi Gharb Afriqiya (The Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa, MUJWA). Meanwhile, following the ousting of the weak Malian forces by the coalition, the MNLA in turn lost control to the armed Islamists.

The West African regional body, the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS), rejected both the military coup and the rebel occupation of north Mali. As part of its overarching strategy for restoring civilian rule in Mali, ECOWAS imposed targeted sanctions on the junta and initiated dialogue with Tuareg rebels and Islamist forces, a dialogue that later faltered. The breakdown of dialogue between the government and the rebel groups, and the advance of rebel forces into Konna (which lies only 600 kilometres to the northeast of Bamako) prompted France to intervene militarily on 11 January 2013. Against this backdrop, observers have wondered how Mali’s apparent successes turned so quickly into failures, and what security implications the resort to military intervention holds. This piece engages with these emerging concerns.

Roots of Rebellion and Regime Collapse

Several factors combined to fuel the rebellion in north Mali and weaken the regime in Bamako. First, Mali has experienced a recurring pattern of Tuareg-led uprisings against governments in Bamako and ineffective responses by the state. Feeling that the state had neglected and marginalised them, especially in times of drought, nomadic Tuareg fighters launched rebellions in the 1890s, the 1910s, 1962, 1990, and 2006. Unresolved grievances from these rebellions have kept conflict alive. For example, the government’s harsh response to the 1962 rebellion, which included killing herds and poisoning wells, left bitter memories among Tuareg communities. Peace accords and decentralisation initiatives in the 1990s and 2000s, meanwhile, were never effectively implemented. Kidal, Gao, Timbuktu, and the surrounding desert areas remained poor and vulnerable. Within a year of the October 2009 peace accords that ended the 2006 rebellion, severe drought struck north Mali, and aid agencies warned of a looming catastrophe. Touré’s decision to launch a $69 million “Special Program for Peace, Security, and Development in northern Mali” in August 2011 did too little too late. By October 2011, when the MNLA was founded, Tuareg discontent was rising once more.

Second, a nexus of criminality and jihadism emerged in north Mali and neighbouring parts of the Sahel during Touré’s time in office. While smuggling in the Sahel dates back centuries, some criminal ventures, and players were new. Since the 1980s and 1990s, there has been increasing traffic of weapons, tobacco, and people across the Sahara into North Africa, and since the 2000s, the trade of cocaine and cannabis has grown.[1] Alongside the drug trade came jihadist factions that emerged from the civil war that began in neighbouring Algeria in 1992. In 2003, the Algerian-born Salafist Group for Preaching and Combat, which rebranded itself 'Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb' (AQIM) in 2007, began kidnapping Western tourists and aid workers in the Saharan-Sahel region. AQIM’s increased interest in Sahelian targets paralleled broader efforts to recruit Mauritanians, Malians, Nigeriens, and others to the group. AQIM and splinter groups have kidnapped Europeans and Americans in Algeria, Mauritania, Niger, and Mali, and recently assisted Nigerian affiliates to carry out kidnappings in north Nigeria. AQIM and its local partners also participate in the drug trade. Kidnapping for ransom and facilitation of drug trafficking have helped AQIM rake in an estimated $100 million. In addition to kidnappings, AQIM has attacked military units and foreign embassies in Mauritania. While it is difficult to track recent micro-trends in religious orientations in north Mali and the surrounding region, several factors seem to have won jihadists a small but crucial number of Saharan-Sahelian recruits: the preaching of hardliners, intermarriage and other social ties to local communities,[2] the allure of money and jihad, and frustration among youth over poverty. Well before the MNLA launched its rebellion in January 2012, jihadist groups had an established presence in north Mali.

Third, corruption in Touré’s regime weakened state institutions, undermined popular faith in the political system, and enabled the predatory activity of criminal and jihadist groups in the north. In a move that symbolised growing concern about the regime’s corruption, the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria suspended two grants to Mali and terminated a third in 2010, asserting that grant funds had ended up in officials’ pockets. This scandal led to formal investigations of Health Minister, Ibrahim Oumar Toure, and about fourteen other government employees in 2011. Perceptions of pervasive corruption and allegations that President Touré had won through fraud in both 2002 and 2007 made some Malians feel that their democracy was a sham, and that their leaders were unaccountable. Corruption weakened the military, a trend with ramifications for the north, where Touré left a few soldiers after a 2009 peace accord. As kidnappings and terrorist attacks ticked upwards in the north, some observers accused state officials of complicity. The figure of Baba Ould Sheik, a northern mayor involved in major hostage negotiations in 2003 and 2009, raised questions about the nature of ties between local officials and AQIM. Further questions were raised in June 2009, when AQIM assassinated Lieutenant Colonel Lamana Ould Cheikh, a senior counterterrorism official, in his home in Timbuktu. As such, corruption and complicity engendered cynicism in the south while abetting criminality in the north.

Fourth, regional troubles intensified Mali’s problems. Algeria, Mauritania, Niger, and Mali struggled to craft a shared framework for fighting terrorism. Despite the establishment of a joint command centre in Tamanrasset in 2010, and several regional summits, these governments held different attitudes toward AQIM. For example, when Mali negotiated a prisoner exchange with AQIM in February 2010, Algeria and Mauritania withdrew their ambassadors in protest.[3] As regional counterterrorism cooperation faltered, the civil war in Libya in 2011 dispersed weapons and fighters throughout the Sahel. Tuaregs who had fought for Gaddafi, a long time manipulator of Sahelian politics and fair-weather friend, returned to Mali to join the MNLA and other armed groups. Libyan weapons increased such groups’ firepower. Seasoned fighters with powerful weapons faced an underfunded, understaffed, and under-equipped Malian army, and drove them out of town after town starting in January 2012.

The Transition to Islamist Dominance

Between January and April 2012, the MNLA and other Islamists groups conquered much of north Mali. The MNLA’s military victories accelerated with the coup against Touré on 22 March 2012. On 6 April 2012, the MNLA formally declared independence for Azawad. Yet in the ensuing months, the MNLA lost political and military control of the region. A secular movement, it was quickly side-lined by Islamists who had little interest in MNLA’s aspirations for an independent homeland in Azawad, and set about implementing strict shari'ah law. After defeating the MNLA in battles in Timbuktu, Kidal, Gao, and elsewhere, Ansar Dine and its allies declared on 28 June 2012 that they have established control on all of north Mali.[4]Ansar Dine was formed toward the end of 2011 by a veteran 1990s Tuareg rebel leader named Iyad Ag Ghaly. Ghaly had been a mainstream figure in Tuareg rebel politics for many years.

The MNLA made two critical political errors. First, it failed to attract important local powerbrokers to its coalition, notably Ghaly, who had worn different hats as a rebel commander in the 1990s, a negotiator during the 2006-2009 rebellion, and a born-again Islamist.[5] Ghaly’s decision to form Ansar Dine may both express his newfound religious convictions and represent a move to outmanoeuvre the MNLA by tapping into religious aspirations. Religion and Ansar Dine’s vision of an Islamic Mali, rather than a secular and independent Azawad, provided an ideological cord that bound a coalition that was larger, better armed, and tougher than the MNLA. Attempts in May and June 2012 to negotiate a merger between the MNLA and Ansar Dine failed after a brief moment of unity.

Second, the MNLA antagonised civilians in the north. Refugees fleeing the region in early 2012 reported that MNLA fighters had robbed and raped civilians, and that disorder was growing in areas they ostensibly controlled. When Islamist fighters began to drive the MNLA from northern cities and towns, they found some support among local populations desperate for law, order, and aid. Ansar Dine and its allies distributed food and promised justice to attract more local support. However, some northerners decried or fled the version of Islamic law that Islamists worked to implement while others welcomed or at least tolerated the system. After the Islamist coalition established control of north Mali, a de facto partition of the country held through the latter half of 2012. While the northwestern region of Timbuktu was controlled by a top AQIM commander from Algeria, the town of Gao, to the east, was controlled by MUJWA, and Kidal, north of Gao, was run by Ghaly.

Faltering Negotiation and the Road to Military Intervention

Faced with the evolving Islamist threat, the interim government of Mali in September 2012 requested the assistance of ECOWAS to suppress the rebellion. ECOWAS, however, adopted a two-pronged approach to the crisis. First, it gave President Blaise Compaoré of Burkina Faso the task of negotiating with Ansar Dine representatives, hoping to get Ansar Dine to cut ties with AQIM and broker a peace deal. After a peace talks in mid-November 2012 in Ouagadougou with Compaoré, Ansar Dine promised to reject extremism and terrorism, fight trans-border organised crime and engage in dialogue with all parties in the Mali crisis. Another Ansar Dine delegation held negotiations in Algeria in a bid to end the crisis.

Second, ECOWAS sustained its diplomatic pressure for military intervention should negotiation fail. As such, it forwarded the interim Malian government's request for assistance in suppressing the rebellion to the United Nation Security Council (UNSC). On 12 October, the UNSC adopted Resolution No. 2071, authorising ECOWAS and the African Union (AU) to develop a plan for international military intervention in Mali and report back in 45 days. In response, military experts from Africa, the UN and Europe held a week-long meeting in Bamako, where they drew up a preliminary blueprint for the deployment of about 3,000-4,000 troops to recapture north Mali from al Qaeda-linked rebel groups.

After a meeting on 11 November 2012 in Abuja, ECOWAS unanimously agreed on an intervention force of 3,300 to retake north Mali from Islamist rebels. The ECOWAS decision was forwarded to the AU, and the AU Peace and Security Council in turn endorsed the proposed ECOWAS military plan. The AU Peace and Security Council Commissioner Ramtane Lamamra stated at a press conference in Addis Ababa on 13 November 2012 that "it has been decided therefore today in light of all the relevant factors to endorse the harmonised concept of operations for the planned deployment of AFISMA, which is the African Union Led Mission in Support of Mali".[6] The military plan was later presented to the UNSC as mandated by Resolution No. 2071.

In Resolution No. 2085 (adopted on 20 December 2012), the UNSC authorised the deployment of AFISMA to Mali for an initial period of one year. The resolution also urged the transitional authorities of Mali to expeditiously put a credible framework in place for negotiations with all parties in north Mali who have cut off all ties to terrorist organisations. Due to obvious challenges relating to funding, training, capacity and logistics, and so on, actual deployment was considered practicable as of September or October 2013.

ECOWAS nonetheless continued its negotiation with the Islamist rebels. During a meeting with President Compaore on 3 January 2013, Ansar Dine demanded autonomy for the north and the rule of shar'iah law. However, after a second round of talks between Ansar Dine, the MNLA and the Malian government held in Ouagadougou, Ansar Dine leader Iyad Ag Ghaly revoked its peace pledge. He accused the Malian government of preparing for war during peace talks by engaging in large-scale recruitment of fighters and former mercenaries from Liberia, Sierra Leone and the Ivory Coast.

Following faltering negotiations in Ouagadougou and Algiers, Islamist fighters began a series of minor military assaults, taking towns such as Lere and Menaka from local militias and the MNLA. Since January 2013, Islamist fighters have mounted a more serious campaign, pushing into the Mopti region of central Mali and attempting to conquer towns like Konna and Sevaré, perhaps in hopes of seizing key infrastructure (such as an airport) that outside militaries had hoped to use in an eventual intervention in the north. Islamist incursion into Mopti triggered alarm in government circles in Bamako and Paris. The move into Konna just 70 kilometres north of the government's stronghold in Sevare was read by France as a clear threat to Bamako. There were genuine fears that the dispirited Malian army would simply crumble in the face of further assault from Islamist fighters. Following a joint assault by the AQIM, Ansar Dine and MUJWA on the town of Konna, Mali's interim president, Dioncounda Traoré, implored France on 10 January 2013 to come to Mali’s aid.

Franco-African Military Intervention: AFISMA

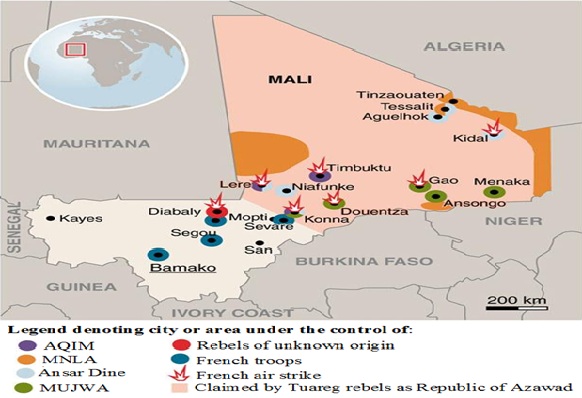

Based on President Traoré’s request and given the extant approval of UNSC Resolution 2085 for deployment of AFISMA, France deployed its forces in Operation Serval on 11 January 2013 to stop the advance of Islamists group who were intent on invading Bamako. French Mirage and Rafale fighter jets mounted air strikes across a wide belt of Islamist strongholds, from Gao and Kidal in the northeast, near the Algerian border, to the western town of Lere, close to Mauritania (Figure 1). France's air and ground assaults on rebel strongholds and outposts have enabled French and Malian forces to retake Konna, Douentza, Gao, Timbuktu and Kidal with hopes of capturing more territories from the Islamists. French warplanes dispatched from France and Chad targeted areas within Mali, covering an operational distance of nearly 2,000 kilometres, from east to west.[7] France plans to eventually increase the number of its ground troops to as many as 3700, as it confronts battle-hardened and well-armed Islamist fighters.

Figure 1: Map of Mali Conflict Landscape Showing Stronghold of Forces and Air Strikes.[8]

|

The French Foreign Minister, Laurent Fabius, claims that the objectives of French intervention are to assist the Malian army in stopping the progress of Islamist rebels southward, protect the integrity of the Malian state, and help rescue French hostages. Analysts, however, contend that French intervention is more related to France's quest to protect and preserve its vital national interests in the region. The strategic importance of the region to France becomes clearer when one considers the wealth in the country’s interior: the gas and mineral resources located close to the Algerian oil fields which are much coveted by the French and within walking distance of locations that have displayed positive exploration indicators in Mauritania.[9] Added to this cocktail is the fact that approximately 6,000 French citizens live in Mali, and French hostages among other Westerners are prime targets of kidnapping by Al-Qaeda linked groups operating in the Sahara-Sahel region.

Furthermore, an estimated 20% of France’s electricity is generated from its nuclear power industry which depends on uranium from the Sahel, especially mines in Niger, Mali’s northeastern neighbour. This explains why in its intervention, France quickly deployed its Special Forces and military hardware to help protect the Paris-owned Areva’s uranium production sites at Arlit and Imouraren in Niger. Thus, French interests are at stake in Mali and the Sahara-Sahel region in general. French intervention therefore is a move to guarantee effective control of an area that was traditionally considered a centre of special influence due to its former colonial presence but is becoming increasingly unstable in ways that pose serious threat to regional and global security.

France's speedy intervention was commended by Malians and regional West African leaders. The international community is also forthcoming with financial pledges to help Mali defeats the Islamist rebels. The AU agreed to contribute $50 million; Japan pledged $120 million; Germany $20 million; India and China $1 million each; and the United States $96 million.[10]

A West African force composed of troops from Benin, Burkina Faso, Niger, Nigeria, Togo, and Senegal, are trickling it to join French forces and roll back the Islamist advance and occupation of north Mali. With a dozen African nations (including forces from Chad, Tanzania, South Africa and Rwanda) promising to contribute forces, an estimated 8,000 African troops are expected to eventually take over the mission. The case of Nigeria’s contributions (so far about $34 million, 900 combat soldiers and 300 air force personnel) to resolving the crisis merits special mention for two major reasons. First, as West Africa’s economic powerhouse with vast military strength and experience in peacekeeping, many believe that Nigeria should play a prominent role in the military intervention. Second, and perhaps more importantly, is the threat of growing ideological and tactical nexus between Mali’s Islamist groups and two Nigerian jihadist affiliates— the Jama’atu Ahlissunnah Lidda’awati wal Jihad (or Boko Haram)[11] and the Jama’atu Ansarul Muslimina fi Biladis-Sudan (JAMBS). Nigeria’s intervention therefore serves its strategic interest in preventing north Mali from providing safe havens for Islamists that threaten its existence as a secular state.

Possible Security Trajectories

The military intervention of French and West African troops in north Mali has changed the trajectory of the crisis. The fast-moving offensive has led to the loss of territory by the fizzle assortment of Islamist rebels seeking the creation of Islamic state. What these Islamist groups earlier boasted of in the form of possession of sophisticated weapons is being decimated through aerial bombardment by French forces. If the Franco-African forces sustain the tempo of aerial and ground-combing assaults, further loss of territory will compel the Islamist groups to re-strategise as they retreat or melt into the local population. This could change the landscape of security within and outside Africa. Accordingly, the following extrapolations are made:

-

The Adoption of Dramatic Terror Tactics within Mali: As Franco-African forces push north to recover territory gained by Islamist militants, the Islamists will employ urban guerrillaism or increase the use of terrorist tactics hitherto applied since their occupation of northern Mali. Possible future tactics will include drive-by-shooting, targeted assassination, gruesome beheading of captured forces, use of improvised explosive devices (IED), and suicide bombing against targets (critical infrastructure, Malian and foreign forces, and government officials, among others). Islamist fighters with experience from Afghanistan, Iraq and Pakistan will play a key role in creating this new security landscape.

-

Attacks by Local Affiliates and Sympathetic Groups: There is the possibility of increased attacks by local jihadist affiliates and groups sympathetic to the course of Mali Islamists, especially in the territories of countries contributing troops to the Mali mission. Diverse civilian and military targets located in such states will be the prime targets of attacks. Nigeria has already witnessed attacks staged by the JAMBS in solidarity with the Mali Islamists. On 19 December 2012, Francis Colump, a French citizen working for the French company, Vergnet, in Katsina State was kidnapped by JAMBS, citing France’s push for military intervention in Mali as a justification. In protest of Nigeria’s contribution of troops to Mali, the JAMBS ambushed a truck on 19 January 2012 conveying Mali-bound Nigeria soldiers in Kogi State, killing two soldiers and injuring others. It is feared that both Boko Haram and the JAMBS will ramp up their attacks on Nigerian soil, with the latter focusing on foreign targets and the former complementing with attacks on local targets. These signpost possible actions local jihadist affiliates and sympathisers of Mali Islamists rebels could conduct in the states of the region in upcoming days or months.

-

Spectacular and Tentacular Attacks: Another possible outcome of the intervention will be the staging of ‘spectacular’ and ‘tentacular’ attacks by jihadist groups with links to al-Qaeda targeting French and Western interests. The spectacular attacks will be conducted on African soil, and are likely to succeed given ineffectual national security and the structure of intelligence in most African states. The recent incident at the In Amenas gas plant in Algeria is instructive. On 16 January 2013, suspected members of Al-Mulathameen Brigade ("The Masked Brigade" or "Those Who Sign with Blood") founded by a veteran jihadist, Mokhtar Belmokhtar, took hundreds of workers hostage at the gas plant. The four-day siege ended when Algerian forces invaded the plant, resulting in heavy human casualties. In total, 685 Algerian workers and 107 of the 132 foreigners working at the plant were freed, while 37 hostages and 32 terrorists were killed. Some analysts doubt any linkage between French military intervention and the In Amenas attack on the grounds that such a large-scale operation will require enormous logistical planning and resources to be conducted in such a very short time. However, Belmokhtar’s vast knowledge of the Algerian terrain as well as ties with local communities across the Sahel makes such spectacular retributive attack possible. In fact, almost immediately after the In Amenas hostage saga, the Al-Mulathameen Brigade released a statement promising further attacks against countries sending troops to Mali. In Europe and elsewhere around the world, jihadist with links to al-Qaeda or individuals radicalised by Islamist rhetoric against the intervention in Mali are likely to execute tenetacular attacks on vulnerable targets in retribution for the intervention in Mali. Such attacks will come more in the form of ‘lone-wolf’ than large scale attacks.

Conclusion

French military intervention in Mali has recorded some initial successes including the recapture of important towns and the salvation of the weak transitional government in Bamako from the fangs of invading Islamist rebels. Whether the war will end soon or drag on remains very unclear. What is clear, however, is that military intervention will have consequences for security within and outside Africa. This will and should not deter international efforts to restore stability and democratic government in the country. However, for sustainable peace and security to be achieved, there are a number of recommendations:

-

Through the ECOWAS Contact Group on Mali, the international community should support the transitional government and Mali’s political elite in implementing broad political and governance reforms that could enthrone genuine democratic rule in Mali.

-

The transitional government in Mali should be supported in its comprehensive strategy of reforming and rebuilding the army and other security agencies.

-

Central, West and North African countries should develop a robust tri-regional mechanism to combat security challenges in the Sahara-Sahel region, with emphasis on intelligence sharing, border security and control of organised trafficking flows – drug, humans, arms, weapons, explosives and fighters.

-

Franco-African forces should invest in building strong and cordial relations with local groups in north Mali to effectively deny the rebel groups of active or passive support by the local population. Franco-African and Malian forces must avoid violating the rights of people as they battle the Islamists.

-

Franco-African forces need to develop and implement broad-based information or psychological operations strategy to counter the jihadist narrative that intervention aims to 'demolish the Islamic Empire of Mali.' The strategy should be implemented by the transitional government, and countries (especially with substantial Muslim populations) sending troops to Mali need to do same to counter the intended undertone of radicalisation.

-

ECOWAS should support Mali to develop and implement a broad strategy of national reconciliation, with emphasis on addressing the issues of the state and negotiations for solutions to issues of injustice to and marginalisation of the Tuareg and Arabs.

Freedom C. Onuoha is a Research Fellow at the Centre for Strategic Research and Studies, National Defence College, Abuja, Nigeria; and Alex Thurston is a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Religious Studies at Northwestern University, United States.

References

[1]Wolfram Lacher, Organized Crime and Conflict in the Sahel-Sahara Region, Carnegie Papers, September 2012,

[2]Tanguy Berthemet, “Comment l’Aqmi a pris place dans le desert malien,” Le Figaro, 22 September 2010, http://www.lefigaro.fr/international/2010/09/22/01003-20100922ARTFIG00669-comment-l-aqmi-a-pris-place-dans-le-desert-malien.php.

[3]Alex Thurston, “Mali: Camatte Released, Algeria Recalls Ambassador,” Sahel Blog, 24 February 2010, http://sahelblog.wordpress.com/2010/02/24/mali-camatte-released-algeria-recalls-ambassador/.

[4]Reuters, “Islamists declare full control of Mali's north,” 28 June 2012, http://www.trust.org/alertnet/news/islamists-declare-full-control-of-malis-north/.

[5] Serge Daniel, “Mali rebel Iyad Ag Ghaly: Inscrutable Master of the Desert,” AFP, 5 April 2012, http://www.google.com/hostednews/afp/article/ALeqM5j2E5T3FzSZKJ-OhCpfHOdsoA0idA?docId=CNG.479d25a6bbe0d8ec222921f745502da0.1f1.

[6]Press TV, “AU approves plan to send ECOWAS troops to Mali,” 14 November 2012, http://presstv.com/detail/2012/11/14/272106/au-greenlights-ecowas-troops-to-mali/.

[7]Finian Cunningham, “Preplanned Mali Invasion reveals France's Neo-colonialistic Agenda,” 14 January 2013, http://presstv.com/detail/2013/01/14/283503/france-invasion-of-mali-preplanned/

[8]Brian Fung, "A Map of the Bewildering Mali Conflict," The Atlantic, 16 January 2013, http://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2013/01/a-map-of-the-bewildering-mali-conflict/267257/?utm_source=Africa+Center+for+Strategic+Studies+-+Media+Review+for+January+17%2C+2013.

[9]Al Jazeera Center for Studies, "French Intervention in Mali: Causes and Consequences," 20 January 2013.

[10]Whitney Eulich, “Mali: French bring the troops, world now bringing the funds,” Christian Science Monitor, 29 January 2013, http://www.csmonitor.com/World/terrorism-security/2013/0129/Mali-French-bring-the-troops-world-now-bringing-the-funds-video.

[11]Freedom C Onuoha, “Boko Haram’s Tactical Evolution,” African Defence Forum, Vol. 4, No. 4, (2011), pp. 26-33.