Tensions in the South China Sea, which has a raft of territorial disputes between several states in the region, have been rising sharply over the past year. The territorial row in the South China Sea has a number of criss-crossing claims disputed by the key countries in the region. China’s recent land reclamation activities, in support of its expansive “nine-dash line”, have fundamentally altered the status quo in the region. While other states, including Vietnam and the Philippines, have also engaged in land reclamation, their pace of construction and intent to militarize is not congruent with Beijing’s efforts.

Introduction

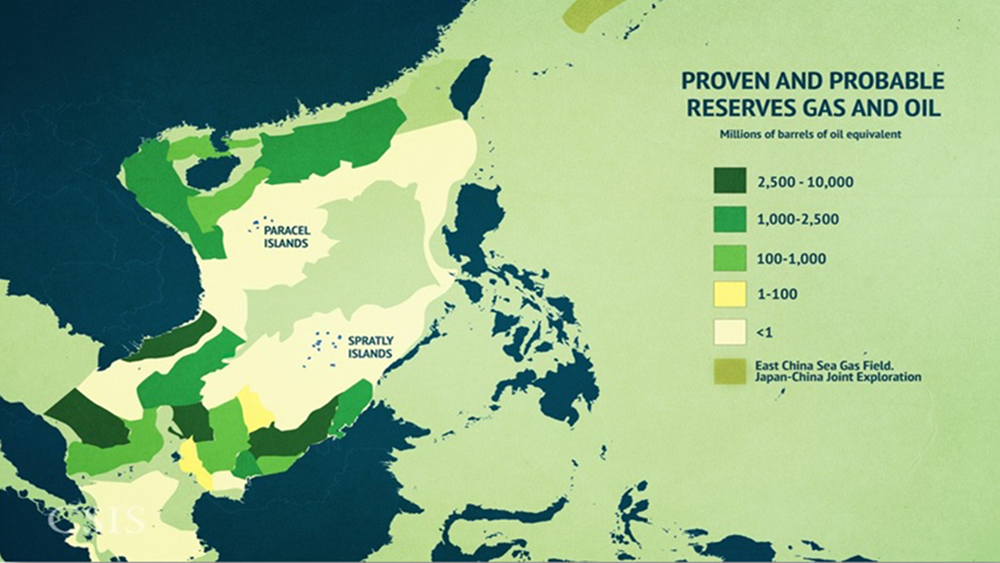

The South China Sea has become a critical issue over the past few years and has the potential to evolve into areas of conflict if risks are not mitigated. The massive body of water is a vital maritime artery for global commerce and more than half of the world’s commercial shipping (by tonnage) transits through the Sea. The value of this trade exceeds $5 trillion per year – more than the GDP of India and all the countries of the Association of South East Asian Nations (ASEAN) combined.(1) The area has a raft of overlapping territorial disputes with a number of claimants in the region. In addition to China’s expansive claims, there are other states with competing territorial and jurisdictional claims including: the Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia, Brunei and Taiwan. In addition to disputes over the rights to resources in the South China Sea, there is also a real concern from the US and other claimants that Beijing is attempting to restrict the freedom of navigation – rules underwritten by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

Land Reclamation and Freedom of Navigation

Tensions in the South China Sea have risen dramatically over the past year as China tries to alter the status quo through massive land reclamation and island construction activities. Beijing’s land reclamation strategy in the South China Sea has escalated at such a pace that Washington has opted to change gears in its approach to seeking a diplomatic and multilateral resolution in the South China Sea. China’s creation of artificial islands in the Spratlys Islands has resulted in a public showdown through which the US has accused China of attempting to force its way to de-facto control in the disputed seas. President Barack Obama has been frank in his assessment(2) of Beijing’s strategy: “Where we get concerned with China is where it is not necessarily abiding by international norms and rules, and is using its sheer size and muscle to force countries into subordinate positions.”(3) These comments were put even more bluntly by Admiral Harry Harris, commander of the Pacific Fleet, who remarked that China “is creating a great wall of sand with dredges and bulldozers”.(4)

This has reached a critical point ahead of this summer’s looming decision by the United Nations (UN)- backed Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) which is studying a case, submitted by the Philippines against China, regarding the right of Manila to exploit natural resources in the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) extending from territory it claims in the South China Sea. The ruling from the PCA, along with recent election of a new President in the Philippines – Rodrigo Duterte, creates a challenging backdrop for the dispute in the coming months. Duterte has indicated his desire to have direct bilateral negotiations with Beijing on the issue – a significant divergence from his predecessor who favoured a united multilateral approach with other ASEAN states.

In response to China’s ramping up of activities ahead of the PCA decision, the US continues to push forward on its Freedom of Navigations Operations in the disputed waters – much to the ire of China, which has the most expansive claim in the area. Additionally, there is little sign that Beijing will halt its expeditious pace of land reclamation in the area and indeed looks to be solidifying its presence through a sustained buildup of infrastructure on key re-claimed features such as Mischief and Fiery Cross Reefs.

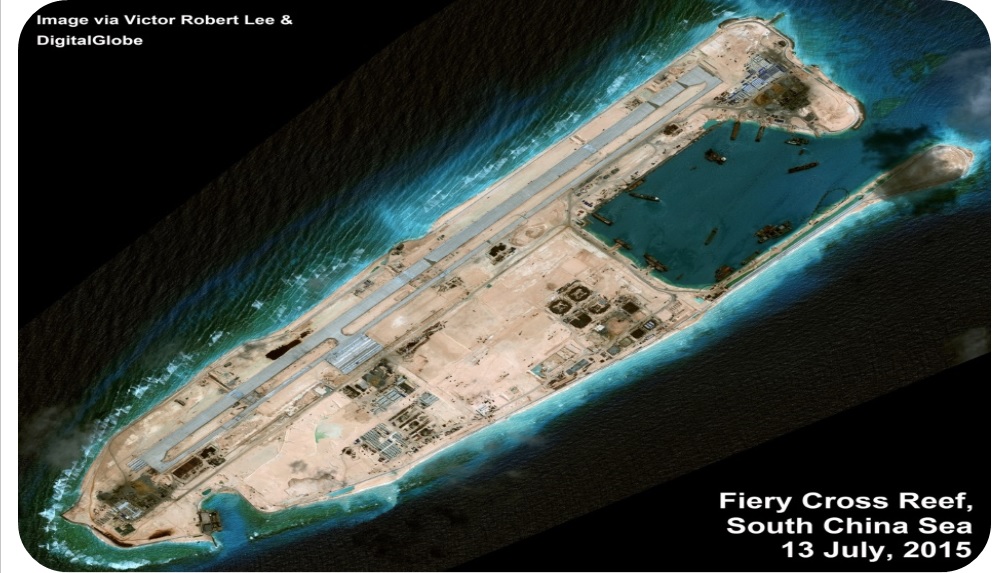

As China ramps up its land reclamation activities in the South China Sea, there is a loose coalition – led by Washington and its regional allies – that is upping the stakes in an effort to deter Beijing from looking to coercively change the status-quo in the disputed seas. One of the principal countries at loggerheads with China in the South China Sea is the Philippines – a US treaty ally. The recent spike in tensions came over the past several months and has been well documented with several high-definition satellite images of land reclamation and construction on Chinese controlled features in the Spratly Islands, whose sovereignty is disputed by China and the Philippines. The Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) has released several photos chronicling Beijing’s rapid expansion and construction of infrastructure on Mischief Reef, Fiery Cross Reef and several other reefs in the Spratlys. Aside from the legal implications, the US approach to issue is being watched closely by its allies and partners in the region.

|

| Source: CSIS AMTI |

China and the Philippines have reached a critical juncture in their dispute over territory in the South China Sea. The case brought forth by the Philippines is now being looked at by an arbitral tribunal at The Hague – which will determine whether the case has enough merit to be heard. Manila’s argument rests on challenging China’s sovereignty claims under Article 287 and Annex VII of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), to which both China and the Philippines are state parties.

Militarization and ADIZ

But while the land reclamation projects are likely to continue over the coming months, there is another move that could be on the horizon for China. The projects could potentially permit Beijing to utilize more tools to push its influence in the South China Sea – such as long-range radar, advanced missile systems and eventually even aircraft. Indeed, the Chinese have completed construction of an airfield on Fiery Cross Reef – which is claimed by the Philippines, Vietnam and Taiwan – despite protests from Washington, its allies and partners. These developments are changing the status quo and effectively that would allow Beijing to assert its control in the skies around the disputed sea.

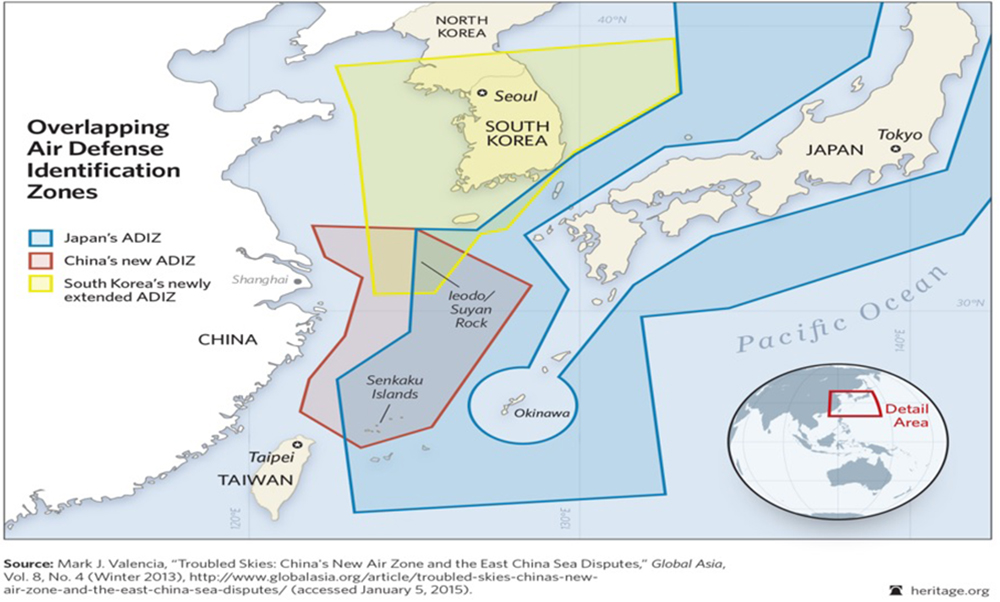

Specifically, these moves lay the foundation for China’s potential unilateral declaration of an Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) in the South China Sea. This would essentially oblige aircrafts flying in the zone to accommodate a number of rules including: the identification of flight plans, the presence of any transponders and two-way radio communication with Chinese authorities. Last year, there had been reports that working-level defense officials in China has already begun drafting the plans for the ADIZ in the South China Sea. Beijing officially pushed back on this notion shortly after these reports though claiming that “the Chinese side has yet to feel any air security threat from the ASEAN countries and is optimistic about its relations with the neighboring countries and the general situation in the South China Sea region.”

But, of course, China also maintains that it is well within its rights to impose an ADIZ in its sovereign territory if and when it chooses. This should be the concern with the South China Sea ADIZ as Beijing essentially positions itself where is can enforce de-facto control over the skies. The official declaration of the ADIZ is less important and will be kept in the back pocket should tensions rise or if China feels that its claim is threatened. China is essentially preconditioning the ADIZ on the behaviour of other claimants in the South China Sea and using the threat of its imposition as additional leverage.

This approach should not surprise anyone in the region. In November 2013, Beijing unilaterally announced an ADIZ in the East China Sea which covered the skies over a significant amount territory – including the Senkaku Islands - claimed and administered by Japan. China’s ADIZ in the East China Sea also overlapped with a pre-existing Japanese ADIZ. To make matters worse, the air zone also stoked tensions with South Korea as it also covered the disputed Ieodo reef – claimed by both Beijing and Seoul. The East China Sea ADIZ was strongly condemned by Japan and the US as a provocation. Beijing’s decision to play this card was as a largely a result of stagnant progress on pressuring Japan to acknowledge the presence of a dispute over the Senkaku Islands in the East China Sea.

So, how soon might China take the step and declare an ADIZ in the South China Sea? The decision remains a political choice for Beijing as it would result in a severe diplomatic backlash in the ASEAN region and also with the United States. Logistically however, the declaration could come anytime this year, especially with the upcoming PCA ruling that is likely to repudiate China’s land reclamation activities. US Admiral Samuel Locklear, head of the US Pacific Command, testified last year to Congress that the recent land reclamation: “allows them (China) to exert basically greater influence over what’s now a contested area. And it may be a platform if they ever wanted to establish an air defense identification zone.” This gray area gives China the option and leverage of the ADIZ without suffering any of the diplomatic consequences of its imposition.

Indeed, there are already concerns that China is moving toward this direction through coercive tactics to limit the freedom of navigation in the skies. Earlier this month, the United States Department of Defense accused China of conducting an “unsafe” interception of one its military surveillance planes in the skies over the South China Sea. Beijing also scrambled jets earlier this month when the United States conducted a freedom of navigation operation near a Chinese controlled disputed reef in the waters.(5)

Conclusion

There will be sustained volatility in the South China Sea over the coming months. While tensions between China and other claimants – such as the Philippines and Vietnam – will be of key importance, the most critical trend to watch is the growing strategic competition between Washington and Beijing. How the US – in its current election cycle – and China manage this area of contention will shape their ability to mitigate risks and the potential for unintended clashes in the near future.

(1) Bonnie Glaser, “Armed Clash in the South China Sea,” Council on Foreign Relations, April 2012. http://www.cfr.org/world/armed-clash-south-china-sea/p27883

(2) Matt Spetalnick and Ben Blanchard, “Obama says concerned China bullying others in South China Sea,” http://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-obama-china- idUSKBN0N02HT20150410

(3) Matt Spetalnick and Ben Blanchard, “Obama Says Concerned China Bullying Others in South China Sea,” Reuters, April 10, 2015. http://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-obama-china-idUSKBN0N02HT20150410

(4) “Balancing China’s Great Wall of Sand,” American Interest, March, 2015. http://www.the-american-interest.com/2015/03/31/balancing-on-chinas-great-wall-of-sand/

(5) Idress Ali and Megha Rajagopalan, “Chinese jets intercept US military plane over South China Sea: Pentagon,” Reuters, May 19, 2016. http://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-china-south-china-sea-idUSKCN0Y92ZA