The Trump era has surrounded the globe with uncertainty on a number of issues, ranging from security, climate change and global trade. During his first week as President, Trump officially signed an executive order withdrawing the United States from the Trans-Pacific Partnership – a large free trade deal that would bring together twelve states from the Asia-Pacific region and encompass nearly 40% of the world’s gross domestic product (GDP). The apparent death of the TPP is only one element though, as Trump has personified a sort of neo-protectionist narrative that demonizes global trade agreements. These developments in the US, along with other global trends pushing against international trade – such as Brexit in the UK, will lead to deep uncertainty and challenges in trying to push ahead the global trade agenda in the coming years.

Introduction

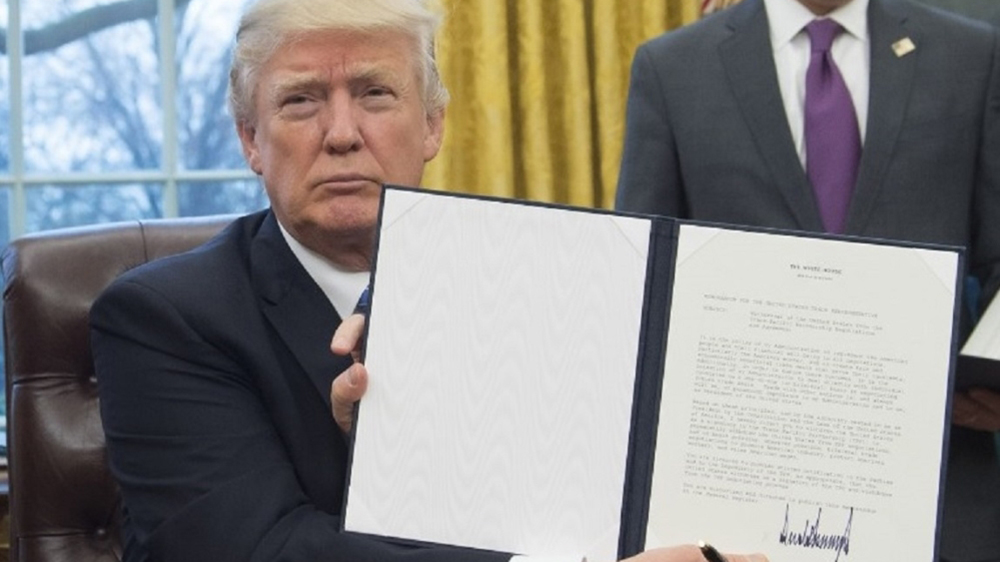

In the first days of the Donald Trump administration in the United States, the President followed through on his campaign pledge to withdraw the United States from the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP).(1) Trump had railed against the deal – which was facilitated through US leadership during the Obama administration – as a “disaster” for the US economy and jobs. In doing so, Trump challenged decades of US efforts in the region to promote liberal trade practices and advocate for strong rules and governance in the economic and trade realms. The failure to follow-through on the TPP has also led many US allies in the region – including Japan and Australia – to question Washington’s commitment to a comprehensive strategy to the Asia-Pacific region.

But the TPP decision is simply one element of the gradual trend against global trade over the past few years. President Trump has also railed against the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) and has accused US neighbours – especially Mexico – of “ripping off” Washington for years through overly favourable trade terms. Since taking office, President Trump has subsequently sent notice to Mexico and Canada that he will be looking towards renegotiating NAFTA aiming for more favourable terms for the US.(2)

Wither TPP?

The collapse of the TPP, given its death knell by Trump’s executive order, will have strategic consequences not only for US policy in the Asia-Pacific, but also to the global trade regime. The TPP was the leitmotif standard for regional free trade agreements and its signature was seen as a triumph for trade liberalization amongst years of intractability in the World Trade Organization’s Doha Round negotiations. During last November’s leader’s summit of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) in Peru, the members of Pacific-rim trade group re-asserted the importance of free trade in a joint communiqué. The APEC economies, including the United States, further committed to “keep our markets open and to fight against all forms of protectionism” – an intentional push back to the growth of protectionist rhetoric, especially from Washington and its about face on the TPP.

The Whitehouse’s executive order on the TPP explicitly stressed the new administration’s allergy to multilateral trade agreements: “It is the policy of my (President Donald J. Trump) Administration to represent the American people and their financial well-being in all negotiations, particularly the American worker, and to create fair and economically beneficial trade deals that serve their interests. Additionally, in order to ensure these outcomes, it is the intention of my Administration to deal directly with individual countries on a one-on-one (or bilateral) basis in negotiating future trade deals.”(3)

The TPP’s failure – at least in the near term – is a tough body blow to key US allies, especially Japan, and also to other important regional states in Southeast Asia – such as Vietnam and Singapore, which viewed the deal as the litmus test of Washington’s commitment to Asia. In addition to the economic dividends, the TPP differs from other large trade agreements as a result of its commitment – which took years of gruelling negotiations – to setting a standard for high-level free trade. Essentially, the TPP is intended to be pact that does not just lower tariff rates and provide market access, but goes the extra mile by insisting on intensive structural and regulatory reforms amongst the signatories. Many of these commitments for reforms come at a high political cost for US allies and emerging friends in the region – like Japan and Vietnam – who are now stuck with a decision on whether to scrap the deal which they invested so much time and capital, or accept a “TPP-lite” without the US for the foreseeable future.

But perhaps as important as the economic benefits, is the strategic importance of the deal. The TPP is meant to bridge the gap and connect Washington’s Asia policy into a long-term strategy. The TPP has the potential to be the strategic glue that binds the region not only to the United States, but also enhances regional economic interdependence and cooperation. Rather than rely on the traditional “hub and spoke” model of US engagement in Asia that focuses on bilateral relationships and alliances, the TPP is meant to support a more integrated and overlapping network – led by the United States – that connects like-minded countries in the region. This is an essential ingredient for most states in the region that, while having deep interests in nurturing economic ties with China, are desperately looking for a hedge to Sino-centric economic order in region.

The back step on the TPP has re-energized agreements largely led by China, including the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP). While many members overlap between the TPP and RCEP, the most striking difference is the absence of the US in the latter. Beijing may also look to pry away at US influence in the region through work to finalize its trilateral trade negotiations with Japan and South Korea. China already inked a bilateral deal with South Korea in 2015. Other possible avenues would be the Free Trade Agreement in the Asia-Pacific (FTAAP) – an idealistic APEC-led initiative that would include both the US and China (although this agreement seems unlikely anytime soon).

Opening the door to China has significant consequences to liberal trade in the region. The TPP was based on open-regionalism in trade terms with strong protections and innovations, rather than just focussing on the low-hanging fruit of trade negotiations such as tariff reductions.

Shunning of Mega-Regional Agreements

One of President Trump’s key campaign pledges has been to renegotiate – with the threat of US withdrawal – the NAFTA agreement with its two neighbours, Mexico and Canada. Shortly after taking office in January, President Trump stressed: “We will be starting negotiations having to do with NAFTA. We are going to start renegotiating on NAFTA, on immigration and on security at the border.” Since this point, the Trump administration has taken a decidedly softer stance to its northern neighbor, while continuing to amp up rhetoric aimed at pressuring Mexico.

Trump has also seized the trend in global antipathy towards mega-trade agreements and economic integration. The clearest example of this was the United Kingdom’s surprising decision – labelled Brexit – to leave the European Union. There was a hope that the failure of the WTO to bring closure to the Doha negotiations would open the door for mega-regional FTAs, such as the TPP and the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP), to fill the gap. This notion has been fundamentally challenged and perhaps has been setback for decades due to global trends.

The potential silver-lining of the intractability of the mega-regional deals is that there is even more urgency now applied to restarting negotiations at the WTO and coming to a compromise to conclude the Doha round. Another element of positivity is that the reliance on bilateral deals and the WTO has the potential to erode geopolitical blocs that were forming as a result of the mega-regional deals. For example, the TPP was largely viewed in Beijing as a pact aimed at constraining China’s rise – effectively led by the United States and Japan, which had broader strategic objectives. Similarly, there remains much concern about the motives and intentions behind the Chinese-led RCEP and other China-led initiatives in the region such as the AIIB and the One Belt One Road Initiative.

(1) The Whitehouse, “Presidential Memorandum Regarding Withdrawal of the United States from the Trans-Pacific Partnership Negotiations and Agreement,” https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2017/01/23/presidential-memorandum-regarding-withdrawal-united-states-trans-pacific

(2) Kristen Walker, “Trump to Sign Executive Order on Plan to Renegotiate NAFTA With Mexico, Canada,” CNBC, January 23, 2017. http://www.cnbc.com/2017/01/23/trump-to-sign-executive-order-to-r enegotiate-nafta-and-intent-to-leave-tpp.html

(3) The Whitehouse, “Presidential Memorandum Regarding Withdrawal of the United States from the Trans-Pacific Partnership Negotiations and Agreement,” https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2017/01/23/presidential-memorandum-regarding-withdrawal-united-states-trans-pacific