As the impeachment saga continues to pivot around Donald Trump’s presidency, Americans have been perplexed by his ability to navigate through his political battles with a sense of risking the reputation and values of the Republican Party. Some observers have argued the recent fierce debate on Capitol Hill was not simply “an impeachment inquiry into an unscrupulous president; it was the ongoing, deepening complicity and corruption of the party he leads.” (1) Peter Wehner, senior fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center, asserts Trump acted the way he did “should surprise exactly no one, given his disordered personality and Nietzschean ethic, his pathological lying and brutishness and bullying, and his history of personal and professional depravity. The president is a deeply damaged human being—and therefore a deeply dangerous president.” (2)

The New York Times’ Editorial Board have termed the current situation as “the Crisis of the Republican Party”, recalling McCarthyism and Senator Margaret Chase Smith’s “Declaration of Conscience”. They highlight the fact that the Party of Lincoln “is again confronting a crisis of conscience, one that has been gathering force ever since Donald Trump captured the party’s nomination in 2016. Afraid of his political influence, and delighted with his largely conservative agenda, party leaders have compromised again and again, swallowing their criticisms and tacitly if not openly endorsing presidential behavior they would have excoriated in a Democrat.” (3) Many Republicans are weighing whether Trumpism has been an asset or a liability to their party.

In this part 2 of his paper, Dr. Solon Simmons of George Mason University notices the Party of Lincoln is in desperate need of narrative transformation. He proposes some strategies for the Republican Party renewal after charting the development of the Republican narrative, using his newly-developed analytical framework “Root Narrative theory”. (4) This innovative approach builds on the basic intuition that the kinds of deep-rooted conflicts, which lead to ideological polarization and extended cycles of violence and misunderstanding, are propelled by rival interpretations of the abuse of power.

Part 1 can be accessed through:

Part 1 of the paper showed how the four-category root narrative profile gives us significant insight into the moral imagination of the Republican Party over time period and shows us some of the ways it has changed. It conforms to some rough ideas we might have about what it is that moves American conservatives and how they might relate to conflict. We can see the deep history of the commitment to liberty, even as it has faded in use over the century, and how a turn to egalitarian rhetoric coincides with the rise of the Reagan Democrats or the white working-class voter of Donald Trump. Nevertheless, the four-category profile conceals as much as it reveals; it does not show us how revolutionary the Republican Party has become and where it might look to reform itself if it hopes to climb out from the hole it has dug for itself in global affairs.

Reconstruction Republicanism: Ideas for the Renewal of the Republican Party

The promise of Root Narrative Theory is not just to promote better analyses of political worldviews, but also to provide practitioners with better points of entry for intellectual transformation. The idea is that if you can meet people in their own political reality, you have a better chance of negotiating with them and finding paths to more productive cooperation. The need for better negotiation and productive cooperation with the Republican Party is abundantly clear. President Trump has taken the party out of its longer-term narrative pattern and nothing in his actions points to much success on his chosen road. The vilification of foreigners is not an alien aspect of Republican Party discourse, but it is clearly exaggerated in his formulations. The retreat from a philosophy of human rights and liberty is on clear display and undermines America’s appeal to leadership in the developing world. The retreat from a concern for stability in global and domestic affairs is matched by a general sense of chaos in both arenas.

Clearly, something must be done to help the Republican Party to climb out of the abyss it has fallen. Keep in mind that these recommendations can be made from a place of rivalry or even contempt. Even if you hate the Republican Party and all it stands for, unless you believe that it is positioned to fall from power utterly, to be cast from the halls of history to exist as nothing but a memory, you have an interest in helping the party back to a better version of itself. Great parties left to flounder in degradation can be some of the most dangerous entities in history, especially those with vast nuclear arsenals at their disposal.

For those who love the party and its traditionalist vision of America, the case for Republican Renewal is all the more obvious. This is the party that stands for unobstructed liberty, for the sanctity of property and for stability through unity, values central to the conservative. In either case, whether viewed as principled adversary or advocate of justice, all of us have an interest in the narrative renewal of the Republican Party after Trump’s neo-realism.

Where might we look first? Let us begin with the Defense Narrative, the one that warns about the threat to the State from foreign aggressors, promoting an ‘us vs. them’ orientation. There is little doubt that President Trump has exaggerated the centrality of this narrative to the Republican Party, but it is a stable enough feature of Republican rhetoric and so recently elaborated that it makes sense to think about how to introduce moral complexity into stories of this kind to turn them in more productive directions.

The convention speech of the elder George Bush might provide some clues for how this might be done. There he made the following claim after speaking about the promising spread of democracy in places like Angola, Namibia, and Iran: “It's a watershed. It is no accident. It happened when we acted on the ancient knowledge that strength and clarity lead to peace; weakness and ambivalence lead to war. You see, weakness tempts aggressors. Strength stops them. I will not allow this country to be made weak again, never.” (5)

This is certainly no dovish rhetoric, but you can immediately see how it is quite different from the sort of defense narrative that Donald Trump might make. Trump is more likely to say something like this line from his convention speech, “This is the legacy of Hillary Clinton: death, destruction and weakness.” In Bush’s version, there is a solid appeal to strength here that could easily put off a typical Democrat, but it speaks in a powerful way to the links Republicans have traditionally made between the securitarian imagination and the pursuit of democratic values. Bush’s story embodied hope for a better world, the very thing that people have always admired about America. In contrast, Trump appears resigned to bitterness and isolation, the very picture of the ugly American.

There is little doubt that this urge to spread democracy around the world can lead to hubris and American overreach, but it is at least an admirable fault when it appears in leaders like the younger Bush, whose skills and story carried through the events of 9/11. We can see the foreshadowing of Bush’s attitude after the 9/11 attacks in his own convention speech version of the defense story, “We heard it during World War II, when General Eisenhower told paratroopers on D-Day morning not to worry — and one replied, “We’re not worried, General … It’s Hitler’s turn to worry now.” A foreshadow of his own story told in the ruins of the twin towers, “I can hear you, the rest of the world hears you, and the people who knocked these buildings down will hear all of us soon.”

Is it not obvious that this is the story speaking Bush as much as it is Bush speaking the story? The idealistic and yet tough American is a stable feature of the American narrative, and although many Democrats in the middle of the twentieth century were able to adapt to it, it is really the role of Republicans to caretake the image of “peace through strength.” As with all liberal, statist accounts, it speaks to the higher ambitions of the country as a beacon of hope for the world, and now that the party has fallen into decay with the wildness and character flaws of the latest president, it is not hard to see the virtues of this older and more idealistic form of securitarian rhetoric.

To get a sense of the story in its purist form, look to President Harding in 1920, when America could imagine that it could still avoid the foreign entanglements of restive humanity while maintaining in its economic transformation and growing global influence. He stated “It is folly to close our eyes to outstanding facts. Humanity is restive, much of the world is in revolution, the agents of discord and destruction have wrought their tragedy in pathetic Russia, have lighted their torches among other peoples, and hope to see America as a part of the great Red conflagration. Ours is the temple of liberty under the law, and it is ours to call the Sons of Opportunity to its defense. America must not only save herself, but ours must be the appealing voice to sober the world.”

The preceding excerpts are examples of what it would mean to work directly with the Defense Narrative in creative ways as a first step toward the reconstruction of the moral force of the Republican Party, which represents a kind of concession to Donald Trump’s performative change in the Republican narrative. But there are ways to use root narrative structure to pivot to other story structures that can draw energy from defense that have better hope of defusing the often toxic ‘us vs. them’ dynamic that comes from the demonization of foreigners in the context of war.

One strategy is to pivot on the protagonist function, which is the strongest point of affinity between root narratives. This would imply a move within the securitarian imagination from a Defense Narrative strategy to its close cousins, unity or stability. Although stories of overcoming partisanship and selfish factionalism are common in Republican Party rhetoric (the Unity Narrative), the stronger play is likely to move toward the Stability Narrative to capture the hearts and minds of Republican voters.

|

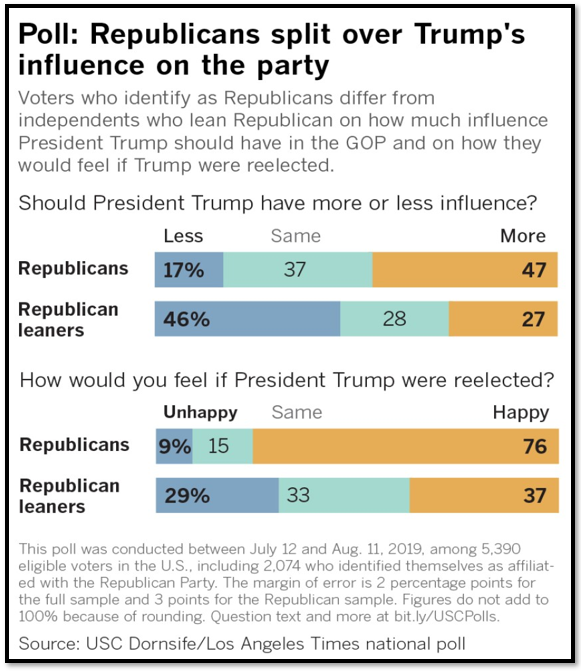

| Republicans split over Trumps' influence on their party [LA Times] |

This is partly because divisions within the country have led to conflict conditions that make the average Republican perhaps more fearful of the Democrats than of ISIS. At least ISIS is weak and distant and its leaders destroyed, while the Democrats and their appeals represent a clear and growing majority of the country. Political polarization has just become too entrenched to make much progress on appeals to unity without strong ideological bolsters in other areas. The stability narrative, with its appeal to strength of leadership in conditions of indecision and mass upheaval is a powerful and ancient conservative appeal, and one that was historically far more salient in Republican Party rhetoric. Consider this thundering voice of stability in Eisenhower’s 1952 convention address: “We are now at a moment in history when, under God, this nation of ours has become the mightiest temporal power and the mightiest spiritual force on earth. The destiny of mankind—the making of a world that will be fit for our children to live in—hangs in the balance on what we say and what we accomplish in these months ahead.”

And Eisenhower’s stern confidence in the leadership of the Republican Party was matched with that of his fellow Republican leaders. Ronald Reagan placed about as much emphasis stability and the power of leadership in the face of chaos as any of his colleagues. He stated “We need rebirth of the American tradition of leadership at every level of government and in private life as well. The United States of America is unique in world history because it has a genius for leaders--many leaders--on many levels… I will not stand by and watch this great country destroy itself under mediocre leadership that drifts from one crisis to the next, eroding our national will and purpose. We have come together here because the American people deserve better from those to whom they entrust our nation's highest offices, and we stand united in our resolve to do something about it.”

This message of strength, not just in the face of implacable foreign enemies, but also when confronting indecision and internal disorder is a guiding thread throughout the history of the Republican Party. It is a party that admires great men, so much so that it runs the risk of falling prey to those who pose as them. Whatever its future, the moral commitment to men, and women, who will serve to stave off chaos is critical for the moral renewal of the party.

The most appealing part of the American version of the stability narrative strategy is the fact that it has always been linked with a conception of progress rather than conservatism in the political reality of the Republican right, a party that in its very name reveals that it is revolutionary and libertarian in contrast to the feudal and militarist states of the past. This somewhat ironic linkage of liberty and stability provides the special sauce that makes it appealing to be a Republican in a fast-changing world. This is clear in the Herbert Hoover case from 1928, whose rhetoric would surely be more ubiquitous if it had not been for the destabilizing disruptions of the Great Depression that handed the stability narrative over to the Democratic Party for a generation.

Hoover stated “It detracts nothing from the character and energy of the American people, it minimizes in no degree the quality of their accomplishments to say that the policies of the Republican Party have played a large part in recuperation from the war and the building of the magnificent progress which shows upon every hand today. I say with emphasis that without the wise policies which the Republican Party has brought into action during this period, no such progress would have been possible.”

In fact, we may have the clue to the Reagan revolution when we look back to this failed moment of Hooverian promise. Reagan was able to perform a kind of rhetorical miracle. He was able to revive the sense of stability that the party had been lost when social justice ideals had an opportunity to prove their appeal with the advent of the New Deal. Reagan knew the true source of the moral strength of the party and he channeled Hooverian themes to capture it in 1980, “The American people, the most generous on earth, who created the highest standard of living, are not going to accept the notion that we can only make a better world for others by moving backwards ourselves. Those who believe we can have no business leading the nation.”

|

| Rep. Matt Gaetz takes a selfie with President Donald Trump after Trump’s State of the Union address in Washington D.C., on Jan. 30, 2018 [Getty] |

These stability stories are examples of strategies of narrative transformation that pivot on the protagonist line, what might be the strongest structural link, but there are opportunities to pivot on the antagonist line as well. The great energy devoted to fighting the Other in the Trump story can be turned to egalitarian ends as well, a story structure in which the Other is imagined as a threat to the solidarity and well-being of the people as a whole. This strategy is a delicate one in that it can quickly turn to some of the darkest ideological rhetoric of any, even venturing into modes of ethnic cleansing and genocide, but at its heart, the Nation Narrative represents an attempt to celebrate all of the members of the political community as whole and to honor their contributions to the collective. It can be a unifying worldview if handled carefully. In its weaponized forms, the Nation Narrative draws energy along the protagonist line from the sorts of reciprocity stories that promise relief to working Americans from unfair terms of trade at work. It’s not hard to turn people’s energy away from anger over exploitation by the rich, to undercutting by the outsider. Trump does this all the time, “Decades of record immigration have produced lower wages and higher unemployment for our citizens, especially for African-American and Latino workers. We are going to have an immigration system that works, but one that works for the American people.”

The excerpt above is the dark form of the Nation Narrative, but it need not be used to demonize foreign economic competition, it can also be used to celebrate the people and their accomplishments in a non-vilifying mode. This is important because as Tocqueville said of democracies, they do not long tolerate those who question their pride. Insofar as the Republican party has been the force that places the stress on American pride, it also promotes a more virtuous use of the Nation Narrative and might well protect the country from the invidious appeals to pride that have been typical of late.

|

| George Bush's outlook [NOQ report] |

Again, it was the elder George Bush who was among the best at telling this type of story, “And this has been called the American Century because, in it, we were the dominant force for good in the world. We saved Europe, cured polio, went to the moon and lit the world with our culture. And now we're on the verge of a new century, and what country's name will it bear? I say it will be another American century.”

This kind of storytelling is extremely difficult for Democrats and those on the left to accept, because it is specifically opposed to the kinds of dignitarian appeals that give strength to efforts to promote diversity and inclusion in American society. Although one might hope that the Party of Lincoln would return to its concerns for the oppressed, this is not a likely outcome. Instead the sorts of romantic appeals to national distinction are far more likely to speak to the increasingly beleaguered white population, which although in decline in relative terms, has electoral weight that can lead the nation in cataclysm for decades to come if it is pilloried without a decent champion.

This need of a people for a romantic self-concept may be one of the critical sources Donald Trump’s strength. If even darker forms of this story are to be prevented, surely the country would be better off in the balance if there were leaders who could tell the American story the way that Ronald Reagan did in 1980.He asserted “It is impossible to capture in words the splendor of this vast continent which God has granted as our portion of this creation. There are no words to express the extraordinary strength and character of this breed of people we call Americans.’

Again, the business of conflict resolution is to find new ways to get parties to understand one another and to come to agreement. This type of story is an indelible part of the American scene and someone will tell it no matter how bitterly it is attacked and no matter how appealingly alternative stories are promoted. Tomorrow’s Republican Party will tell stories of American Exceptionalism and American pride. The only question is, will they be apocalyptic attacks on others as we have recently seen or attempts to shore up a sense of destiny as was typical of the history of the parties most successful partisans. This story from Harding in 1920 is an example of the latter, “Here is a temple of liberty no storms may shake, here are the altars of freedom no passions shall destroy. It was American in conception, American in its building, it shall be American in the fulfillment. Sectional once, we are all American now, and we mean to be all Americans to all the world.”

|

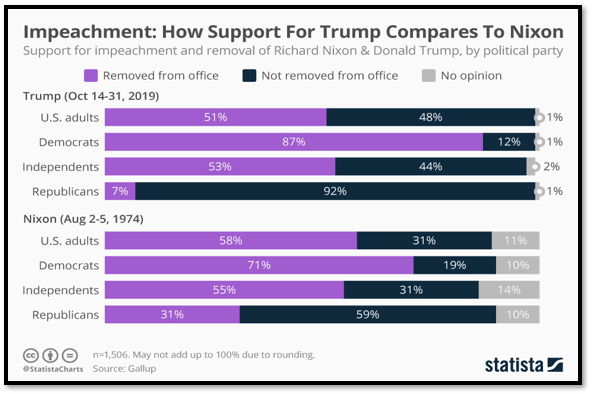

| A comparative look at the impeachment dynamics between Trump and Nixon [Statista] |

Is there Hope for Republican Renewal?

It is very easy to take cheap shots at the Republican Party under the leadership of Donald Trump. It requires no partisan view to recognize how far the moral authority of the party and the nation have fallen under his leadership. In a photo for the ages, in which Nancy Pelosi confronts the president over his betrayal of the nation’s allies, the Kurds in Syria, it is Republican leaning generals who hang their heads in shame, seemingly knowing that what they stand for is not as it should be. Republicans across the spectrum know what is happening to their story and have pointed out Trump’s moral failings long before he came to office. As is often now repeated, Trump was attacked by fellow Republicans as being a “race-baiting, xenophobic, religious bigot” a “terrible human being” and a “narcissist at a level I don’t think this country’s ever seen” (Karni 2019).

This is only small sample of the attacks that have been leveled by prominent and well-positioned Republicans. One can only imagine what others really think of him. The party has fallen on hard times, and because of the historical influence of the Republican Party on global affairs, so has the whole world that it influences. What Trump Secretary of Energy, Rick Perry, said of the president in a 2015 attack can now be generalized: Donald Trump is not only a “cancer on conservatism,” he is now “a cancer on global collaboration” in a world that desperately needs American leadership (Dukakis 2015). If this cancer is to be controlled, it will require that the Republican Party reform itself.

In this paper, I have proposed strategies for Republican Party renewal that are based on a close analysis of the political worldview of the Republican Party’s most successful leaders throughout its period of global leadership. When the period of analysis began in 1920, the United States was a new player in global affairs that had just been moved into prominence by the cataclysm of the First World War. By the end of the period in 2016, the United States had been the leader of the coalition of nations that supported global visions that took names from American initiatives: United Nations, Washington Consensus, Free World, etc.

|

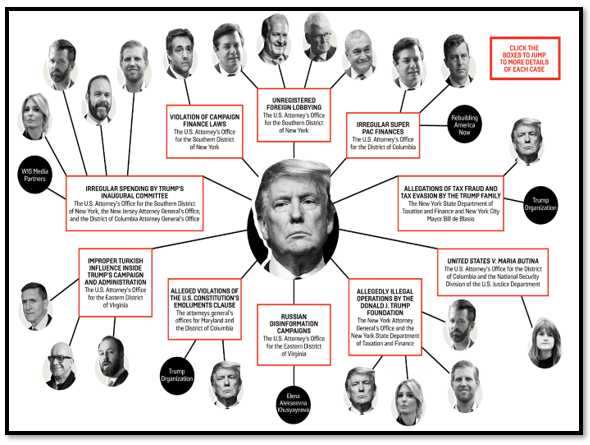

| Controversies around the President's Men [FP] |

After Trump, all of these beacons of American leadership are in jeopardy not only in practical terms but also in terms of moral leadership. It is unclear why anyone outside of the United States would look to cooperate with the kind of America first policy that we have experienced over the past three years. If the Republican Party has hope for renewing its claims for global leadership, and given the alternatives on offer right now even those of us who often vigorously oppose the party should all hope it does, it will have to develop a new narrative, a process that demands that its leaders turn to its own history, its own stories, and its own better angels.

We live in a world of moral complexity. There is no way for a single story or a single broad class of stories, however appealing to dominate. The hearts and minds of the soon to be eight billion people on the planet will require a diverse array of arguments to help them to realize their destinies. Whatever one might think of it, the Republican Party will be a part of that destiny and it is in desperate need of narrative transformation. Strength must again be matched with virtue. Stability must again be linked to the cause of progress. National pride must be based on contribution and respect not birthright and fear. These are the features of the Republican Party at its best, even though we have likely yet to see the party at its worst.

- Peter Wehner, “The Exposure of the Republican Party”, The Atlantic, November 13, 2019 https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2019/11/trumps-republican-party-built-lies/601990/

- Ibid,

- Editorial Board, “The Crisis of the Republican Party”, The New York Times, October 18, 2019 https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/18/opinion/trump-impeachment-republicans.html

- Simmons, Solon. 2019. “The Root Narrative Profile: The Power of Story for Reputation Management.” (Unpublished Manuscript), and Simmons, Solon. 2020. Root Narrative Theory and Conflict Resolution: Power, Justice, and Values. Routledge Studies in Peace and Conflict Resolution. London: Routledge.

- 1988 Republican National Convention: Bush Text: ‘Stakes Are High and Choice Is Crucial’, Associated Press, August 19, 1988 https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1988-08-19-mn-728-story.html