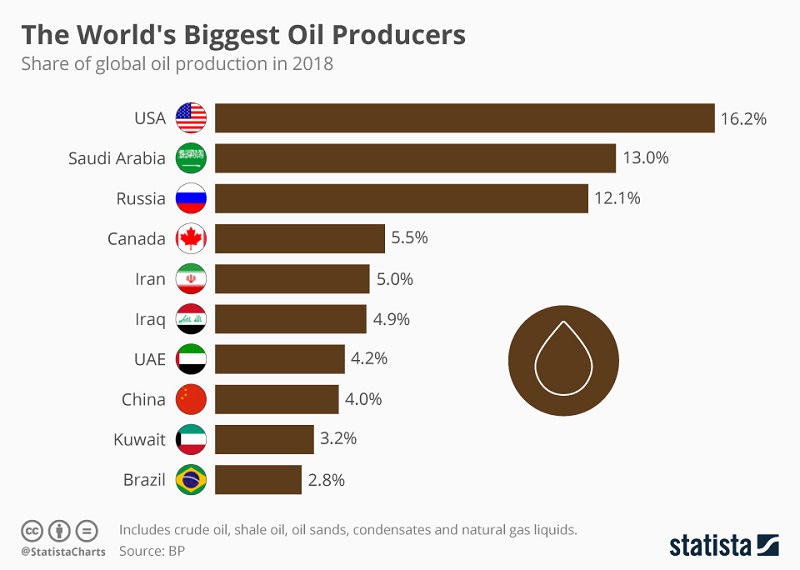

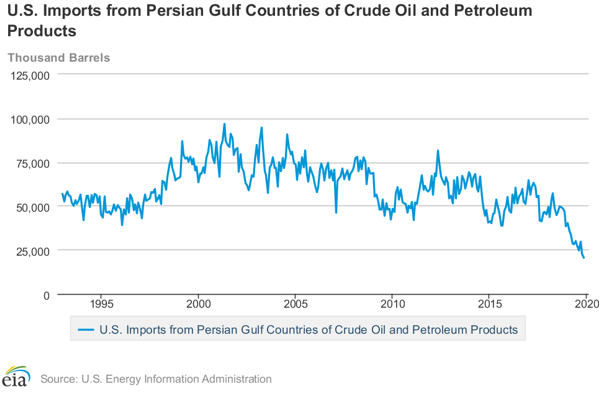

U.S. President Donald J. Trump has temporarily reduced the bleeding by engineering a timeout in an oil price war that pitted Saudi Arabia against Russia and Russia and Saudi Arabia against the United States. Even so, the timeout failed to tie up the loose ends of the suspended price war. Within days of the suspension, Trump was considering a ban on import of Saudi oil in a bid to force the Kingdom to reroute tankers carrying some 40 million barrels of crude to the United States.(1) He explained “The problem is no one is driving a car anywhere in the world, essentially. ... Factories are closed, businesses are closed. We had really a lot of energy to start off with, oil in particular, and then all of a sudden they lost 40%, 50% of their market.”(2)

Trump’s oil production cutting band aid served his immediate purpose as well as that of Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, known by his initials MBS, and Russian President Vladimir Putin. All three men needed to focus on bringing a devastating Coronavirus pandemic under control and addressing its associated global economic collapse. What Trump’s intervention did not do is tackle the underlying cause of the price war and its fallout that could produce tectonic shifts in the political landscape of the Middle East as well as a reconfiguration of oil markets.

As a result, the question is not whether there will be another war for energy market share but when. For Saudi Arabia, and to a lesser extent the United Arab Emirates, it is also a question of how to balance longer-term interest in securing greater market share at the expense of U.S. and Russian producers without further damaging already strained relations with the United States in an environment in which Gulf states have few alternatives. Put differently, the challenge for Saudi Arabia and the UAE is how to manage the emergence of conflicting U.S. and Gulf interests with the need to maintain close political, military and economic ties to the United States, an increasingly unreliable but so far irreplaceable ally.

Bearing the Brunt

So far, Saudi Arabia has been the focus of U.S. wrath at the Kingdom’s perceived insensitivity and recklessness in declaring a price war during an economically-devastating pandemic, while the UAE has managed to fly under the radar despite it too declaring that it would increase production in support of the battle with Russia. The question is for how long the UAE can stay off the radar. There is “ample production capacity that will be quickly brought online given the current circumstances,” UAE Energy Minister Suhail Al Mazrouei said at the outset of the price war signalling which side his country was on.(3) An immediate crisis in relations with the United States was averted with an agreement reached in March between members of the Organization of Oil Exporting Countries (OPEC) and non-OPEC producers to cut production by some 10 million barrels a day.

But, thirteen U.S. Republican Senators from oil-producing states put Saudi Arabia on notice in a two-hour phone call with Saudi Energy Minister, Abdulaziz bin Salman, a day after the agreement. “While we appreciate them taking the first step toward fixing the problem they helped create, the Saudis spent over a month waging war on American oil producers, all while our troops protected theirs. That’s not how friends treat friends. Their actions were inexcusable and won’t be forgotten. Saudi Arabia’s next steps will determine whether our strategic partnership is salvageable,” said North Dakota Senator Kevin Cramer.(4) The Congressmen’s notice reflected deterioration over the past two years of the Kingdom’s relations with Congress, already troubled by the war in Yemen, the Kingdom’s record of human rights abuse, and the killing of journalist Jamal Khashoggi in October 2018 as well as Mr. Trump’s anger at the Saudi price war.

The Senate Republicans also signed a letter to MBS cautioning if he and other OPEC members do not change their course, “their relationship with the United States is going to change very fundamentally,” As Senator Cruz put it. The group of Senators who signed the letter included Ted Cruz of Texas, Dan Sullivan and Lisa Murkowski of Alaska; North Dakota’s Kevin Cramer and John Hoeven; Ron Johnson of Wisconsin; John Cornyn of Texas; John Kennedy and Bill Cassidy of Louisiana; John Barrasso of Wyoming; Tom Cotton of Arkansas and James Lankford and James Inhofe of Oklahoma. They also urged U.S. Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross to investigate whether Saudi Arabia and Russia were breaking international trade laws by flooding the U.S. market with oil. In an April 2 phone call, Trump told Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman that unless OPEC member states started cutting oil production, he would be powerless to stop lawmakers from passing legislation to withdraw U.S. troops from the Kingdom.(5)

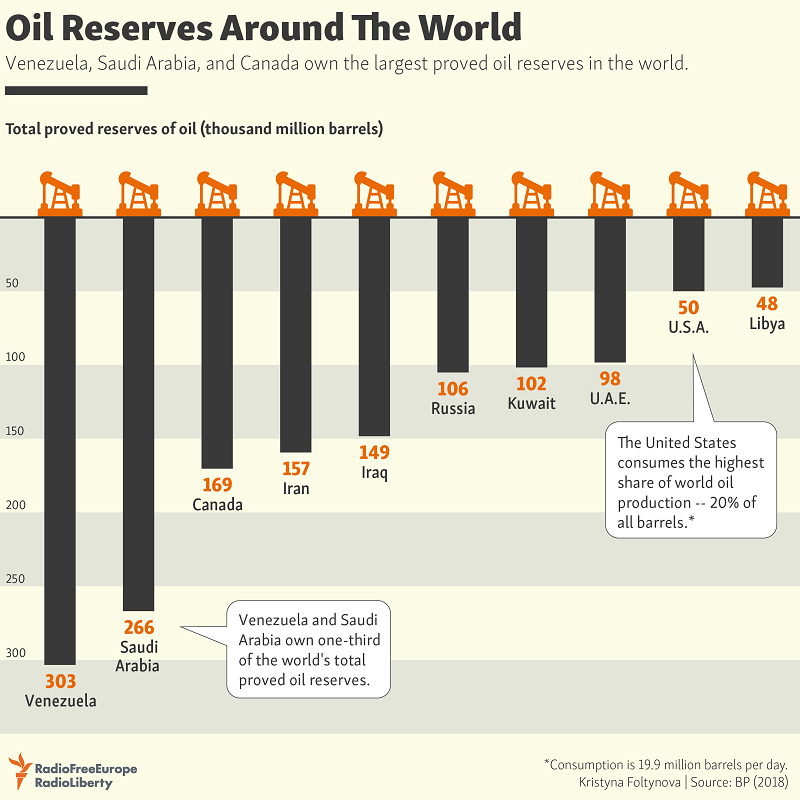

Saudi judiciary reforms in March 2020, including abolishing flogging as a legal punishment and death sentences for people who committed crimes, as minors constituted an effort to deflect criticism; but, were unlikely to turn the tide. There is, however, a silver lining in the U.S.-Saudi clash over oil prices even if it was suspended with the production cut agreement. The clash clarifies the parameters of the long-standing relationship between the two countries. Eager to knock out the U.S. shale industry, which accounts for some 10 million jobs, Saudi Arabia made clear that it would attempt to pursue its interests irrespective of U.S. concerns or the fact that the world was in a massive economic downturn as the result of a pandemic. “The Kingdom will . . . have to reduce its budgetary expenditures while wisely accessing its financial reserves for essential spending as it fights this potentially long-term battle of the fittest for market share in global energy,” said Ali Shihabi, a political analyst and former banker who often reflects Saudi thinking.(6)

The U.S.-Saudi clash has also laid bare the vulnerability of the U.S. shale industry at a critical time. The ability of the United States to project itself as the world’s largest producer and a rising exporter takes on added significance against the backdrop of a decline in U.S. credibility reinforced by America’s inability to get a grip on the coronavirus crisis. By putting Saudi Arabia and by implication the UAE on notice, the Congressmen were drawing battle lines for a renewed clash in the future that may have become even more inevitable as a result of the pandemic and its economic fallout. With a likely reduction of the value of oil reserves and limited new gas stockpiles in the coming decades because of the rise of shale and renewables, Saudi Arabia needs to secure market share by capitalizing on its low costs. Indeed, the Kingdom has one of the world’s lowest costs of production of a barrel of oil.

The collapse in demand, low prices, and the global economic turndown increases the importance of market share. Saudi Arabia is likely to have to downsize its attention-grabbing big tickets like Neom – the futuristic city on the Red Sea and focus on revenue and job-creating sectors. “There’s a high likelihood (Neom) fades into nothingness. . . . The momentum will likely die out. And it will take a lot to rebuild that momentum,” said a Gulf-based economist.(7) Some economists suggest that Saudi Arabia and other oil producers may seek to create jobs and domestic and regional markets for their petrochemicals by pushing the development of plastics processing and chemicals.

Saudi Arabia hinted at a return to a focus on energy derivatives with the acquisition by its sovereign wealth fund of stakes worth roughly $1 billion U.S.D in four major European oil companies: Equinor, Royal Dutch Shell, Total, and Eni. “Managing heightened public expectations of the leadership will be crucial in maintaining public support for MBS when the pandemic subsides. The crisis is also a test for the progress made on Saudi ‘Vision 2030’, especially its programs to transform public services, reduce unemployment, and diversify the economy away from oil,” said Saudi Arabia scholar Yasmine Farouk.(8)

No Good Options

The Coronavirus pandemic and global economic collapse leave Prince Mohamed with only one option: salvaging Saudi-U.S. relations. Russian President Vladimir Putin is unlikely to have taken kindly to a reported shouting match in a phone call with the crown prince at the outset of the price war.(9) Signalling that the production cuts are a ceasefire rather than an end to the war, Saudi Arabia and Russia continue to fight it out on oil markets with the kingdom undercutting Russia with discounts and special offers, according to a Reuters investigation.(10) Strained relations did not prevent the two countries from moving forward with an agreement on Russian wheat sales to the Kingdom in March. A first Russian shipment of 60,000 tons set sale for Saudi Arabia. The ship left port before Russia slapped a ban on all wheat exports.

Irrespective of the state of Saudi-Russian relations, Russia’s call for replacing the U.S. defence umbrella in the Gulf with a multi-lateral security arrangement that would involve the United States as well as China, Europe, and India is a skeleton with no flesh. Russia has neither the wherewithal nor the will to shoulder responsibility for Gulf security. Nor do others, envisioned by Russia as participants in a revised Gulf security arrangement. The proposal, moreover, is a stillborn baby as long as Saudi Arabia refuses to engage with Iran with no pre-conditions. The Kingdom has so far used the pandemic to harden fault lines with the Islamic republic, casting aside opportunities to build bridges with goodwill gestures. Similarly, China has no appetite for a major military role in the Middle East despite having established its first foreign military base in Djibouti; and contributing to anti-piracy operations off the coast of Somalia.

Equally troubling for Prince Mohammed is the fact that he cannot be certain that China would be able to maintain its neutrality if U.S.-Iranian tensions were to explode into an all-out war given that when the chips are down Iran may be of greater strategic significance to Beijing. Iran’s geography, demography, and highly-educated population give it a leg up in its competition with Saudi Arabia for Chinese favour. So, does the fact that China and Iran see each other as bookends at both ends of Asia with civilizational histories that go back thousands of years? Iran, moreover, plays a pivotal role in Belt and Road-related efforts to link China to Europe by a rail that would travers Central Asia and the Islamic republic and end the expensive and time-consuming process of having to transfer goods to ships at one end of the Caspian Sea and loading them back onto a train on the sea’s opposite shore.

Prince Mohammed’s manoeuvring to strike a balance in securing Saudi Arabia’s place in a world of contentious big power relationships is reflected in coverage by the Kingdom’s tightly controlled media of Chinese and U.S. efforts to combat the pandemic. Andrew Leber, a student of Saudi policymaking, noted that “China’s mixed record in boosting its image in Riyadh is a reminder that soft-power competition is not a zero-sum game. Even as Saudi outlets have grown more willing to air criticisms of China, some have derided the efforts of President Donald Trump and his administration to blame COVID-19 on Beijing.”(11) Mr. Leber’s analysis of Saudi media coverage suggests that Prince Mohammed is seeking to keep all doors open. It will, however, take a lot more than vacillating media coverage and reform of the Kingdom’s penal code to polish Saudi Arabia’s tarnished image in the United States and level the playing with Iran when it comes to China.

Bowing to U.S. Pressure

Saudi Arabia’s willingness to at least suspend the price war at Trump’s behest was the latest indication that the Kingdom realized that it had to be careful not to burn its bridges to Washington. It followed the Kingdom’s bowing to U.S. pressure to acquire Lockheed Martin’s Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) system rather than Russia’s S-400 anti-aircraft and anti-missile weapon. President Putin made a last-ditch sales pitch last September after the Kingdom’s six battalions of U.S.-made Patriot batteries failed to detect drone and missile attacks on two of the country’s key oil facilities that knocked out half of its production capacity.

Prince Mohammed’s decision to confront Russia stemmed from a stark choice confronting the crown prince: endanger relations with the only power to have put forward a regional security plan that would have allowed the Kingdom to hedge its bets while maintaining close ties to the United States, or drive oil prices down in a bid to force Russia to coordinate production levels that would ensure a higher price. Ultimately, the Crown Prince’s choice was driven by economics rather than longer-term security, a decision he could yet regret.

Prince Mohammed may in some respects have shot himself in the foot even if he had maintained and won his price war against Russia. The war confirmed foreign investors’ worst fears: Aramco, the Kingdom’s national oil company is as much subject to the crown prince’s whims as it was to sound economics and commercial management despite last year’s limited initial public offering (IPO) on the Saudi stock exchange. “This has proved to investors that their worst fears about Aramco were a reality. The company’s plans and its output decisions are based on MBS’s erratic behaviour,” said a Saudi official familiar with Aramco’s offering.

The Tip of the Iceberg

Oil is but the tip of an iceberg in efforts, particularly in the case of the UAE, to manage a divergence in interests with the United States without tarnishing the country’s carefully groomed image as one of Washington’s closest allies in the Middle East. Differences first emerged with Emirati gestures designed to ensure that the country would not be a target in any military confrontation between the United States and Iran. The UAE began reaching out to Iran last year when it sent a coast guard delegation to Tehran to discuss maritime security in the wake of alleged Iranian attacks on oil tankers off the coast of the Emirates.

The Trump administration remained silent when the UAE last October released U.S. $700 million in frozen Iranian assets that ran counter to U.S. efforts to strangle Iran economically with harsh sanctions. While the United States reportedly blocked an Iranian request for U.S.5 billion from the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to fight the virus, the UAE was among the first nations to facilitate aid shipments to the Islamic republic. The shipments led to a rare March-15-phone call between UAE foreign minister Abdullah bin Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan and his Iranian counterpart, Mohammad Javid Zarif.

UAE officials stressed, however, that there would be no real breakthrough in the Emirati-Iranian relations as long as Iran supported proxies like Hezbollah in Lebanon, pro-Iranian militias in Iraq, and Houthi rebels in Yemen. The UAE gesture contrasted starkly with a Saudi refusal to capitalize on the pandemic. Instead, Saudi Arabia appeared to reinforce battle lines by accusing Iran of “direct responsibility” for the spread of the virus. Government-controlled media charged that Iran’s allies, Qatar and Turkey, had deliberately mismanaged the crisis. Moreover, the Kingdom, backing a U.S. refusal to ease sanctioning of Iran, prevented the Non-Aligned Movement from condemning the Trump administration’s hard line.

Saudi Arabia’s wholehearted support of the Trump administration’s hard line is no guarantee that Riyadh will be shielded from the fallout of heightened U.S.-Iranian tensions spinning out of control. It leaves the Gulf states cautioning the Administration not to “let this get out of hand. You live thousands of miles away. It will be us, not you who pays the price and you won’t be there to rush to our defense.”

A Costly Missed Opportunity

Saudi Arabia’s failure to follow in the UAE’s footsteps could prove to be costlier than meets the eye. The spread of Coronavirus coupled with the global economic breakdown and the collapse of the oil market have somewhat levelled the playing field with Iran with the undermining of the kingdom’s ability to manipulate oil prices as well as its diminished financial muscle.

Add to that the weakening of Saudi Arabia’s claim to leadership of the Islamic world as the custodian of Mecca and Medina, Islam’s two holiest cities, as a result of its efforts to combat the pandemic. One has to go way back in history to find a precedent for the Kingdom’s banning of the Umrah, Islam’s minor pilgrimage to Mecca; the likely cancelling of the haj, Islam’s major pilgrimage that constitutes one of the faith’s five pillars; and the closing down of mosques to avoid congregational prayer. Nonetheless, Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, in a twist of irony given his record on human rights and rule of law, has emerged as a model in some Muslim countries like Pakistan that have been less forceful in imposing physical distancing and lockdowns on ultra-conservative religious communities. “What if this year’s haj was under Imran Khan rather than Mohammad bin Salman? Would he have waffled there as indeed he has in Pakistan?” asked Pakistani nuclear scientist, political analyst and human rights activist Pervez Hoodbhoy referring to the Pakistan prime minister.(12)

Humanitarian Aid = Geopolitics

In a further indication of a divergence of interests, the UAE, according to Middle East Eye, has been trying to sabotage U.S. support for Turkey’s military intervention in northern Syria as well as a Turkish-Russian engineered ceasefire in the region.(13) In other words, the UAE was at odds with Russia, not just with regard to oil, but also Russian efforts to prevent the situation in northern Syria from spiralling out of control and further jeopardizing Moscow’s alliance with Turkey. Middle East Eye reported that UAE Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed had promised Syrian President Bashar al-Assad U.S.$3 billion, $250 million of which was paid upfront, to break the ceasefire in Idlib, one of the last rebel strongholds in Syria.

On opposite ends of the Middle East divide, Prince Mohammed had hoped to tie Turkey up in fighting in Syria, which would complicate Turkish military support for the internationally recognized Libyan government in Tripoli. The UAE aids Libyan rebel forces led by Field Marshal Khalifa Haftar. The outlet said that a tweet by Prince Mohammed on March 28 declaring support for Syria in the fight against the coronavirus was designed to keep secret the real reason for the UAE payment. “I discussed with Syrian President Bashar al-Assad by phone the repercussions of the spread of the coronavirus and assured him of the UAE’s support of and assistance for the brotherly Syrian people in these exceptional circumstances. Human solidarity in times of adversity supersedes all else, Sisterly Syria will not be alone in these difficult circumstances,” Prince Mohammed said.(14)

It is unlikely that Prince Mohammed’s explanations will convince policymakers in Washington. Nevertheless, the United States, Saudi Arabia and the UAE are likely to paper over cracks in their relations in the short term facilitated by a pandemic and economic crisis that leaves no one untouched. It probably is, however, only a matter of time for cracks to re-appear.

(1) Irina Slav, U.S. Ban On Saudi Oil Could Force Riyadh To Reroute 40 Million Barrels, OilPrice.com, 23 April 2020, https://oilprice.com/Energy/Crude-Oil/US-Ban-On-Saudi-Oil-Could-Force-R…

(2) Jeff Mason, “Trump to consider halting Saudi oil imports, says U.S. has 'plenty'”, Reuters, April 21, 2020 https://www.reuters.com/article/us-global-oil-trump/trump-to-consider-h…

(3) Verity Ratcliffe and Anthony Di Paola, Abu Dhabi Plans Big Oil Output Boost to Join the Price War, Bloomberg, 11 March 2020, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-03-11/abu-dhabi-s-adnoc-wi…

(4) Kylie Atwood and Jeremy Herb, US oil state senators threaten to rethink ties to Saudi Arabia in fiery call with ambassador, CNN, 11 April 2020, https://edition.cnn.com/2020/04/10/politics/us-oil-state-senators-saudi…

(5) Timothy Gardner, Steve Holland, Dmitry Zhdannikov, Rania El Gamal, “Special Report: Trump told Saudi: Cut oil supply or lose U.S. military support – sources”, Reuters, April 30, 2020 https://www.reuters.com/article/us-global-oil-trump-saudi-specialreport…

(6) Ali Shihabi, Saudi Arabia, Russia, and Aramco: The end of OPEC+, Al Arabiya, 15 March 2020, https://english.alarabiya.net/en/views/news/middle-east/2020/03/15/The-…

(7) Alison Tahmizian Meuse, Saudi futuristic city turns into a mirage in Covid-19 era, Asia Times, 7 April 2020, https://asiatimes.com/2020/04/saudi-futuristic-city-turns-mirage-in-cov…

(8) Yasmine Farouk, Updating Traditions: Saudi Arabia’s Coronavirus Response, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 7 April 2020, https://carnegieendowment.org/2020/04/07/updating-traditions-saudi-arab…

(9) David Hearst, EXCLUSIVE: Saudis launched oil price war after 'MBS shouting match with Putin,' Middle East Eye, 21 April 2020, https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/exclusive-saudis-launched-oil-price-…

(10) Olga Yagova, Saudi Arabia gets physical with Russia in underground oil bout, Reuters, 20 April 2020, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-global-oil-saudi-russia-analysis/sau…

(11) Andrew Leber, China and Covid-19 in Saudi Arabia, War on the Rocks, 23 April 2020, https://warontherocks.com/2020/04/china-and-covid-19-in-saudi-media/

(12) Pervez Hoodbhoy, Corona — our debt to Darwin, Dawn, 4 April 2020, https://www.dawn.com/news/1546317/corona-our-debt-to-darwin

(13) David Hearst, EXCLUSIVE: Mohammed bin Zayed pushed Assad to break Idlib ceasefire, Middle East Eye, 8 April 2020, https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/abu-dhabi-crown-prince-mbz-assad-bre…

(14) Mohammed bin Zayed, Twitter, https://twitter.com/MohamedBinZayed/status/1243613323519762432