On 23 November 2012, the General Assembly of the United Nations issued resolution No. 67/19 with a majority of 138 votes against 9 with 41 countries abstaining, by which it ruled to upgrade the status of Palestine in the United Nations to the description of “nonmember state”.

Looking back at the evolution of Palestine’s status in the United Nations, it can be said that the rhythm of this development is characterized by the fact that it is a slow process and that the step which will follow the new status may take a long time, due to the local, regional, and international imbalance of power in favor of Israel.

Indicators of Evolution in the Palestinian Status

The first step in promoting the status of Palestine in the United Nations and its specialized agencies after the approval of the United Nations on 22 November 1974 was represented by the acceptance of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) as a “nonmember entity”. Palestine waited 14 years after that – until December 1988 – for the General Assembly of the United Nations to recognize the name “Palestine” in place of the Palestine Liberation Organization, following the announcement of the Palestinian state at the Palestinian National Council in Algeria in November 1988.

Twenty-three years later, UNESCO took a bold step by recognizing Palestine as a full member (on 31 October 2011), becoming the first specialized agency of the United Nations to grant Palestine this recognition, prompting the United States to stop its financial contributions to the agency.

Although the Palestinian state - which American president Barack Obama proposed would stand next to Israel in September 2011 - was prevented from taking the step toward full membership by the US position in the Security Council, resulting in a call for the postponement of this move, it did take a half step forward with a resolution from the General Assembly recognizing it as a “state”, though not a member.

While the journey towards full recognition and all that entails is a long one, recent developments mean that the evolution of Palestinian status has the stamp of historical orientation, and this bears a look at the implications thereof in the long term, particularly for Israel.

Palestine: When does it move to Member State?

The transition of Palestine to status as a member state is beholden to both legal and political circumstances.

When considering the history of seeking membership in the United Nations, there have been sixteen countries that passed from “nonmember state” to “member state” status - with Switzerland being the first to do so in 1946, a year after the establishment of the United Nations. However, there is some disparity among the sixteen states in the amount of time it takes to make this transition, as the following table indicates:

|

State |

Number of years it took to shift from non-member state to member state |

|

Switzerland |

1 |

|

South |

42 |

|

Monaco |

37 |

|

Republic |

24 |

|

Federal |

21 |

|

North |

18 |

|

Japan |

4 |

|

Democratic |

3 |

|

Italy |

3 |

|

Finland |

3 |

|

Austria |

3 |

|

German |

1 |

|

Kuwait |

1 |

|

Spain |

Same year |

|

United |

1 |

|

Bangladesh |

1 |

A Transition Period

from Nonmember State to Member State in the United Nations

While there is no doubt that the circumstances of each state’s ascension to membership was differently dependent on the conditions of the state’s emergence as well as the nature of the international environment at the time, there does seem to be an indication that, in addition to legal considerations, there were also political interests at play.

It is necessary to point out here that the UN General Assembly resolution No. 1514 of 1960; the Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples, which is referred to generally as “territorial, not governed autonomously”, can contribute in strengthening the legal position of the nonmember state, making it possible for the Palestinian side to claim particular areas that are not subject to the Palestinian Authority in accordance with the Oslo agreement.

As for the second legal dimension, it seems that Israel, the US and some European countries, particularly the UK, have been concerned about Palestine joining the International Criminal Court (ICC), with the possibility of bringing lawsuits against some Israeli leaders for war crimes.

Palestine’s earlier requests to join the ICC were rejected because of its “non-state” status. But with Palestine’s new status in the UN, it could request to join the ICC again, in which case it could possibly grant the ICC jurisdiction to consider charges of war crimes against Israel retroactively, with regards to the attack on Gaza between 2008 and 2009, as well as the latest attack on Gaza in 2012.

What can we take away from this?

• There has been an evolution in the legal status of Palestine.

• That evolution in status enhances Palestine’s diplomatic position in the international community.

From Legal Recognition to Political Practice

When examining the political gains made by Palestine’s legal recognition, it is possible to note the following:

• The international diplomatic environment strengthened the impression that the 1967 borders are the borders of a future Palestinian state, thus moving them out of the status of “disputed land” to the status of “occupied territories”.

• Virtually all of the Palestinian factions support the move towards statehood (with the exception of statements by Mahmoud Al-Zahar and a silent agreement from Islamic Jihad), indicating that this step contributes to bridging some of the gaps in the Palestinian political collective, and highlighting the positive impact of the steadfastness of resistance fighters in the Gaza Strip in the face of the Israeli attack at the end of 2012.

• These legal developments reflect a slow turn in international public opinion – especially in many European countries, the USA, China, Russia, Japan, and some countries in Latin America and Africa- away from Israel, which is a matter of great diplomatic concern to Israel.

In addition, there have been a handful of recent developments that indicate changes in the international arena which may be to Israel’s detriment, such as:

• A strategic shift of the USA’s attention toward the Pacific region, at the expense of other regions.

• The effects of the global financial economic crisis on the USA’s ability to act in the Middle East and other areas, particularly in terms of using military force.

• The increasingly influential role of emerging countries in the world, especially China and Russia, countries that compete with Israel for attention in the tight spaces of the international stage.

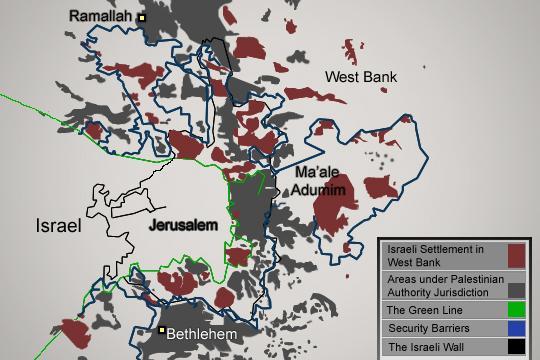

But all this does not discount the difficulty of the actual formation of the Palestinian state. One obstacle is that 82 per cent of the territory of the West Bank is subject to Israeli authority, with about half a million settlers living in about 200 settlements or settlement centers, and they also enjoy the support of conservative and religious Israeli political currents which have been burgeoning since 1977. Moreover, the eastern border of the Palestinian state on the Jordan River does not exist for the Palestinian authority, with the exception of the small area of Jericho.

That means that the formation of the Palestinian state is dependent on the following:

• The removal of 200 settlements or settlement centers. At the moment, the opposite is happening. The Israeli government has increased settlement projects in Jerusalem and other areas at an escalating pace, with Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu indicating that this will continue: “The decision…in the United Nations…is meaningless, and will not change anything on the ground.”

• The Palestinian Authority achieving financial independence. The Palestinian Authority receives internal revenue from taxes and customs, as well external revenue which, importantly, comes primarily from western aid. Israel fully controls the first resource while the second is subject to American and European political sentiment (especially the budget committee in the U.S. Congress), which seems unfavorable for the most part. But out of twenty-seven European countries, there were only nine that did not support the Palestinian position as a nonmember state, with the two main states, Germany and Britain, abstaining. Indeed, the World Bank – despite the fact that it had previously confirmed the efficacy of the Palestinian Authority’s financial management within reasonable limits – it came to reiterate its skepticism of the economic and financial ability of the West Bank and the Gaza Strip to build a state in the future.

• The general uncertainty and instability in the Middle East. Many Arab countries are dealing with the repercussions of the Arab Spring, not to mention to the Syrian crisis, Iraq’s fragile post-war recovery and Iran’s position under the economic blockade, as well as numerous other internal and external economic and political issues. Israel is aware of all of this and adapts its strategies accordingly.

• Palestinian factionalism. Palestinians are split in two ways; geographically and politically. The first is reflected by the fact that Israel completely controls Palestinian communication geographically, separating Palestinian towns from each other in the West Bank, and separating the West Bank from the Gaza Strip, which gives it leverage that can be exploited to a large extent.

As for the political divide, dialogue between Fatah and Hamas regularly fosters hope for cooperation in the Palestinian ranks. However, complete unity would rest on concessions and compromises of strategy; either for Hamas to abandon the armed struggle quietly and incrementally, as Fatah did during the period of 1988-1993, or for Fatah to abandon peaceful resistance based on security coordination with Israel. However, cooperation is subject to the psychological structure of the people in the Palestinian leadership, the nature of the prevailing political culture, and the cognitively and socially organized style, and this does not seem like something either party is prepared to address.

The Map of the Next Negotiation

The Israeli side will seek to take advantage of these complications in the following manner:

• Call attention to the Palestinians’ internal disputes, thereby forcing the Palestinians to the negotiating table at a weaker position.

• Seek to reduce the concept of the Palestinian state to an “entity” rather than a “state”, enabling it to reject withdrawal from all of the settlements, hold onto Jerusalem and the Jordan River, reject the granting of regional airspace for Palestine, and appropriate a large chunk from the West Bank in return for the proposed road between Gaza and the West Bank.

• Push for the gradual Palestinian disassociation from the issue of refugees – and the latest statements of Mahmoud Abbas have indicated that this is the case – which raises further concerns regarding his implied pledge not to bring lawsuits before the International Criminal Court.

• Ensure the longest possible period of not mitigating the crisis in Gaza, which Israel hopes will lead to internal Palestinian disputes.

Considering all these issues, can the journey towards Palestinian legal status overcome these obstacles? While it seems unlikely in the short term, there is a glimmer of hope for the future.

Copyright © 2012 Al Jazeera Centre for Studies, All rights reserved.