|

| [AlJazeera] |

| Abstract Developments in Iraq are important to Iran for a number of reasons. First, Iran aims to formulate a better understanding of the implications of these developments for Iraq and for the region as a whole. Second, they seek to determine the Shia political bloc’s position in Iraq. Finally, Iran wants to monitor challenges and opportunities presented by these developments, especially in terms of how they will affect its national interests and security. Iranian officials have denied that recent developments in Iraq present a new security challenge for them; however, these developments and the increasing likelihood of an autonomous Kurdistan have undeniably raised security concerns within the Islamic Republic. This report evaluates Iran’s growing interest in Iraq’s security and analyses threats and opportunities this represents to Tehran |

Introduction

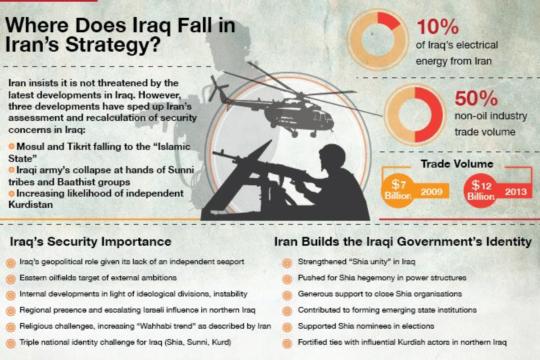

Despite Iranian officials’ denials that recent developments in Iraq present a security threat to the country, the fact that the Islamic State (IS or Daesh) seized control of Mosul and Tikrit has undoubtedly raised alarm bells within Iran’s security establishment. Furthermore, the mobilisation of Sunni tribal groups and Baathists, coupled with the Iraqi army’s collapse, exacerbates these security concerns within Iran.

Iranian interpretations of events in Iraq have varied. Officially, Iran decries the recent events as terrorism, referring to the growing presence of “terrorist groups”. Some analysts place partial blame on the Maliki government, while others regard Sunni Iraqis’ demands as at least partly justifiable. Yet other groups refer to a regional game in which certain countries support “IS puppets” who have proclaimed a “caliphate” in parts of Iraq and Syria. Regardless of the various interpretations, it is obvious that recent developments have positioned Iraq as a high priority for Iranian security strategists. This paper discusses how Iraq’s recent upheavals impact Iran’s security and examines the possibility of threats and opportunities for Tehran.

Developments in Iraq have lead Iran to take a position by addressing the following questions:

• What are the effects of these developments on Iraqi governance, on Iraqi politics and on the region?

• How will the situation affect the Shia political bloc in Iraq?

• What are the challenges and opportunities arising from these developments, and how will they affect the Iranian national interest and Iranian security?

• Will these developments have any impact on Iranian-American relations?

• In the regional context, how will these events affect Iran’s role, and how will they impact Iran’s objectives and strategies, and other regional and non-regional actors?

Post-2003: Power structures and regional identity

Iran’s strategy regarding Iraq took on a new dimension after 2003, following developments that led to fundamental shifts in regional identity and power structures and altered both the political geography and the approach of political players in the Middle East. With the demise of Baath influence and the inclusion of Shia-Kurdish representatives within Iraqi governing and power structures, this re-orientation from “Arab-Sunni” to “Shia-Kurdish” has worked in Iran’s favour and provided Tehran with an opportunity for greater influence and enhancement of its regional role.

Iranian strategy in Iraq is not governed only by internal developments and struggles between various political players, but also by the presence of international powers and other regional players.(1) This is pivotal in the formulation of Iranian political and security strategy toward Iraq. Following the fall of Saddam Hussein’s regime, the Shia presence became a top priority in for Iran’s influence on events in Iraq. This is based on Iran’s support of its allies within the Iraqi political establishment. To achieve this, Iran openly supported the political process in Iraq and its political allies there. However, from an Iranian national security and regional political perspective, the situation in Iraq has remained the same as it was after the American withdrawal and similar to what it was before the invasion. Thus, these recent developments represent an opportunity to enhance Iran’s future regional role and improve its national security at the same time.

Historically, Iraq has played an important role in Iran’s security, and the importance of this relationship continues to the present day – a relationship characterised by a fierce war and a legacy of confrontation and hostility. The terminology of “Arabs and Persians” and “Sunnis and Shias” remains a cause of disagreement and rivalry.

The growing importance of security

After 2003, the importance of Iraq’s security for Iran’s security has increased dramatically, and this importance is highlighted by multi-dimensional political and economic developments.

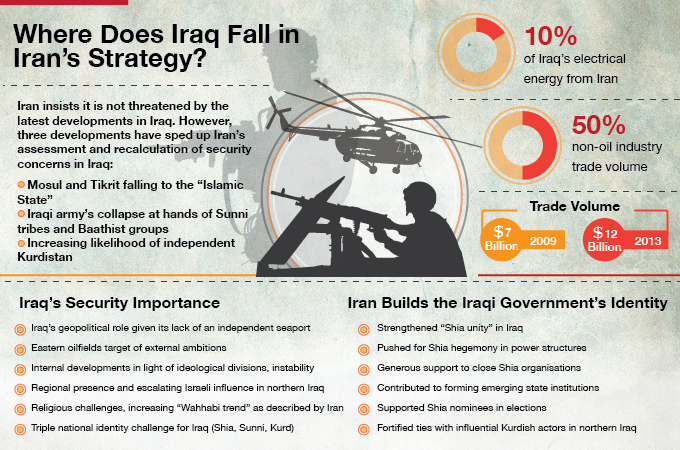

Iraq’s geopolitical role

Iran’s concerns in this regard stem from the fact that Iraq lacks an independent maritime outlet, with its only sea path limited to Shatt al-Arab and a narrow outlet to the Gulf. Similarly, Iraq is linked in the north with narrow straits controlled by Turkey. Eastern Iraq is strategically important since most of the cities, commercial centres and oil fields of economic importance are found in the east, characteristics which have made Iraq vulnerable to foreign ambitions and consequently pose a security concern for Iran.(2)

Despite Iraq’s current state of weakness and political instability, its sensitive geopolitical location in the Arab world and its role in creating regional balance vis-à-vis the other non-Arab powers mean that Iraq’s future is of continuing strategic significance to these powers, particularly to Iran; and Tehran in turn remains an important factor in determining Iraq’s future.

Internal developments

Analysing developments and internal changes in Iraq and their impact on the security equation in Iran, it cannot be said that Iraq still poses a military threat to Iran in the traditional sense. Despite this, the underlying grounds for tension and a security vacuum still exist, as perceived by Iranian security strategists. The new security challenge for Iran originates from existing competition between the nationalist, religious, and political groups and currents in Iraq, which in turn manifests as the absence of stability, sectarian differences and the possibility of a divided Iraq. These are challenges that go beyond the borders of Iraq and impact Iran’s security arena.(3)

Sectarian challenge

Iraq has long been a country where creeds and races meet in a manner that has affected the fabric of power and society. In the past, Sunni control at the apex of the political pyramid had its impact in demarcating the type of relationship between Iran and the other Arab Gulf states. Though the new Iraq has a changed power pyramid with Shia influence reducing sectarian tensions with Iran, the fragile political structure in Iraq today, as well as continuing sectarian differences exacerbated by the growth of what Iran labels the “Wahhabi trend” in the Iraqi arena, mean that the sectarian challenge remains at the forefront of challenges facing Iraq.

Iran seems concerned mainly with the Shia dimension and the unity of “Shia ranks”. This influenced its policy and relations with the Shia and Kurdish parties in Iraq, and it used all of its power to ensure a political process dominated by Shias, particularly those associated strongly with Tehran, to consolidate loyalty. Iran has provided great and multi-faceted support for the Shia Islamic organisations close to it, such as the “Islamic Supreme Council”. Tehran played a major role in involving them in the political process, in addition to playing a role in the formation of nascent state institutions.(4) Iran also consistently advocated the unification of Shia parties in order to convert them to a power that has weight and is capable of sufficient political influence, ensuring Shia control of the government and of the overall political process in Iraq. This Iranian strategy increases with every successive electoral process, as evident in the 2005 and 2010 legislative elections, the 2009 municipal elections, and the 2014 Iraqi parliamentary elections. Iran supported the Shia candidates while maintaining strong relations with influential Kurdish players in northern Iraq.

The enduring Iranian objective in Iraq is a Shia government ideologically compatible with Tehran and can be counted on to support Iran.(5) Although Iran accepted that an alternative to al-Maliki was needed, they knew with certainty that the alternative must be a friend.(6)

National identity challenge

Geopolitics and nationalism in Iraq and their impact on Iranian national security are rooted in the historical bilateral relations between the two countries. The triple demographic identity of Iraq (Shias, Sunnis, Kurds), with citizens from each group represented in various formations, is seen as a dilemma by Iran. With regard to multi-faceted identities, Iranian concern is focused on negative outcomes which might result from this pluralism, especially the possibility of a divided Iraq, a concern which has consistently remained a factor in Iranian foreign policy.(7)

Strategic and political influence

There are two dimensions determining how Iran studies Iraq from a strategic and political perspective. This section will discuss these dimensions.

Dimension one

There is a possibility of moving away from the traditional notion of Iraq as a force to achieve parity with regional powers, to Iraq being a force that supports Iran. This would give Iran the opportunity to redefine Iraq’s regional role both for itself and other forces in a manner that guarantees its existence as an influential regional force and player. This is premised on strengthening Iraqi political personalities and players who support such a policy. The Iranian government is using the theory of “soft power” in Iraq to extend its influence on the country via enhancing economic relations and by supporting the Shia authority in Najaf, as well as influencing Iraqi public opinion through the media.

Iranian “soft power” in Iraq is also reflected in its economic strategy. Tehran has worked to expand economic and trade relations with Iraq, and the 2009 volume of trade exchange between the two countries reached around seven billion dollars. By 2013, the trade exchange volume between Iraq and Iran had increased to twelve billion dollars annually, fifty per cent of which is not dependent on oil industries.(8)

The increases in Iranian exports exceed those from other countries and are focused on cheap food products and consumer goods. Iran also provides Iraq with ten per cent of its electric power needs. Iraq has become the main destination for Iranian visitors, whose numbers swelled to nearly 40,000 pilgrims visiting holy sites throughout the year, in addition to the four million who visit Iraq during Ashura.(9)

Dimension two

Iraq has always been a regional and strategic competitor for Iran, and this point of view argues that Iraq’s current circumstances are caused by weakness; thus, they cannot form the basis of a comprehensive and long-term strategy. Traditional differences with Iran on issues such as geopolitics, Arab world leadership and identity (Arabs and Persians) may resurface. These, in addition to the economic structure and other factors, could mean that once stability is restored and consolidated in Iraq, it will be the most important challenge for Iran, particularly after it regains its regional and strategic influence.

Regional competitors’ interests

With the absence of political stability, Iraq today constitutes both a threat and an opportunity for competing countries in the region.(10) Initially, Saudi Arabia dealt with changes in Iraq in a manner that rejected the new Iraqi authority (one that was characterised in a decline of Sunni forces and a rise of Shia and Kurdish forces). This rejection expressed itself through support of anti-government Sunni groups in Iraq.(11) However, with time, Riyadh became more realistic, accepting the new order and trying to become influential in the political process.(12) Following the latest developments, al-Maliki accused Saudi Arabia of supporting “terrorist groups”, but Riyadh has responded by offering donations to Iraq and seemed eager to show that it does not stand with the Sunni groups accused of “terrorism”. Turkey and Iran share concerns about Iraq’s unity and the consequences of dividing the country, realising that the absence of stability will strengthen claims for further secession and division. The Kurdish issue tops the list of challenges that Turkey faces, while the nature of Turkish relations with Iraq, Turkish superiority and the dependence of Iraq on Turkey in terms of water and communications also plays a role in defining the relationship between the two countries.(13)

In terms of the Kurdish question, the Kurdistan Workers Party’s (PKK) manifesto talks about federation. This, together with the escalation of Israeli influence in Kurdistan, are enduring concerns for both Ankara and Tehran,(14) and the notion of a Kurdish state faces both Turkish and Iranian opposition.(15) Turkey supports a central and capable Iraqi government that will dispel fears of secession, and also seeks to prevent the expansion of Iranian influence, which Turkey views as a cause of instability. Over the past few years, Turkish policy has focused on the prevention of federalism in Iraq, because it believes that any change in Iraqi Kurdistan will significantly affect Turkey’s overall security.(16) Thus, for Turkey, Iraq remains an arena of influence and strategic depth.

The Turkish government’s rejection of an independent Kurdistan may be attributed to various reasons, including:

• Supporting the unity of Iraq and rejecting division is equivalent to standing up for unity of Turkish soil.

• The independence of Iraq’s Kurdistan region is a worrisome model for the Turkish government and could have negative consequences for Iran because the Kurdish issue extends to include Turkey, Syria, Iraq and Iran.(17)

The Turkish position tends to recognize the borders of Iraq according to the 1926 Ankara agreement, but this position is liable to change and Turkey may have to deal with Kurdistan’s independence as inevitable if a referendum is undertaken in this regard.

America and the expansion of Iranian influence

American concern rises from the perpetuation and expansion of Iranian influence in Iraq. The United States considers Iran as an obstacle to its policy in Iraq. Despite this, both sides have found common goals in Iraq, and Washington has followed a policy, at this level, which is based on limited and temporary tactical cooperation with Iran, in parallel with another policy that regards Iran as a security challenge that hinders American influence in Iraq and the region. Iran has pursued a similar policy in return.

With Hassan Rouhani winning the Iranian Presidency in 2013, Iran witnessed a change in its relations with the West in general and with the United States in particular. Iran began to offer cooperation with Washington on specific issues, especially those falling under “anti-terrorism”.(18) Many Iranian officials believe that a successful agreement on the Iranian nuclear issue would close a bitter page in the turbulent relations between the two countries and would open doors to progress in other areas of contention. Perhaps most importantly, such cooperation between the two countries could work to achieve stability in the Middle East.(19) Proponents believe that “along with its allies in the region and with the cooperation of the United States with Iran, a regional security system can be formed to combat the great imminent threat for the interests and security of all concerned parties”. Further, Iranian decision makers “believe that the rise of extremism and Jihadi groups in the current circumstances make it imperative for the United States and Iran not to be in a state of hostility, because the beneficiaries of this situation are terrorist groups”.(20)

Hassan Rouhani’s team speaks in a different tone than that of Iranian leader Ali Khamenei and his speech rejecting American intervention in Iraq.(21) The Iranian Vice President, Hamid Abu Talibi, declared on Twitter, “Iran and the United States are the only countries, from a regional power perspective, that are able to put an end to the crisis of Iraq peacefully”, and he did not rule out the possibility of cooperation.(22)

Threat and opportunity

Iranian officials try to downplay the risks and consequences of developments in Iraq and their implications on Iranian security and on the future of the Iranian role in Iraq. However, since Iraq shares a 900 kilometre-long border with Iran, Iraq’s current situation inevitably poses challenges for Iranian security policymakers, particularly since Iran has pursued a strategy aiming to impose dominance and influence on Iraq over the past few years.

A number of analysts believe that there is a direct challenge for Iran from the recent developments in Iraq. Kayhan Barzegar, a well-known Iranian researcher, talked about the threat that these developments pose for Iranian national security, noting that they represent an ideological extremism expressed in a traditional manner, one opposed to political borders and is anti-democracy and overtly hostile towards Shias, Iran and the nation state.(23)

His view is that the Islamic State (IS) in Iraq “is a problem exceeding (the) few thousand fighters that have rapidly gained control of important sites. What threatens Iran is the presence of regional powers and countries behind these groups”. Iran’s anxiety is exacerbated by the recent tensions in Iran’s relations with other regional states. If the required balance is not restored, that will form grounds for foreign intervention and create conditions for using these groups against the Iranian national interest, hence cooperation between Iran and Saudi Arabia has become a compelling need for both sides and would be in their mutual interest.(24)

Barzegar believes that moderation is the appropriate formula to restore balance to Iran’s regional relations. However, the question today is whether there are still opportunities for moderation in the region after Iran’s policies in Syria and Iraq have opened the door for hostility with the Sunnis and reignited a sectarian war, in one instance enabling Shia militias to enter Syria in accordance with the plans of Qassem Suleimani, Commander of Iran’s al-Quds Force.(25) It is possible that the environment of support for IS would not have been created in the absence of Iranian political interference, especially given the manner in which Suleimani conducted affairs in Iraq and Syria.

Though the Islamic Republic cannot afford to carry out large-scale military operations in Iraq, it has mobilised its forces in the vicinity of Baghdad and has begun to reinforce the armed Shia groups within Iraq – militias which Iran organised and trained over the past year, including the Badr and al-Mahdi armies. This indicates that Iraq has entered a bloody confrontation, and most likely that the Iranian Revolutionary Guards have begun military operations inside Iraq. In recent days, Iran held a funeral for a pilot said to have been killed defending “Aal al-Bait holy sites in Samarra”. The press did not give details about his death and merely published his photograph during the funeral in the city of Shiraz.(26)

Iraqi Kurdistan has come close to achieving independence, and the referendum which Massoud Barazani referenced is the decisive factor in this matter. In the best case scenario, preventing Kurdistan’s independence could be achieved by reducing the role of Shias in the political process in Iraq, a solution that represents a loss for Iran. However, Kurdish independence would expose Iran to real risks, given that its Kurdish citizens comprise ten per cent of the Iranian population and in view of the fact that in recent years Iran’s Kurdish areas have witnessed major confrontations between Iranian security forces and Revolutionary Guards on one hand, and separatist Kurdish groups on the other.

The “anti-terrorism” slogan is applauded within Iranian circles. Just as Iran cooperated with the United States in Afghanistan under the umbrella of the fight against terrorism, it can repeat this in Iraq. Although Afghan intervention has turned into a wider geopolitical game, the collapse of the Iraqi regime represents a failure for both Iran and America. Before the US army was able to occupy Kabul, Iran provided it with military information that aided in bombing sensitive targets in Afghanistan. Despite Iran’s temptation to repeat the experience, its recurrence would be complicated given that it carries related risks and internal and regional consequences. Therefore, the “anti-terrorism” slogan appears necessary in order to give this cooperation legitimacy in the eyes of Iranian public opinion. If Iran succeeds in convincing Saudi Arabia to cooperate with it in Iraq to curb extremist groups, the option of cooperation with Washington will decline.

Iran’s benefits from the “anti-terrorism” slogan go beyond its relations with the US and represent an opportunity to change the image of Iran in the world. While the Arab world appears to be lagging behind, drowning in its problems and ruled by a loose strategy, Iran seems stable and calm with a firm and solid strategy.(27) What has helped in building this image of Iran, which Dr. Sajjadpour talks about, is the fact that, for the first time in history, the majority of Iranians are educated and live in cities, and Iran enjoys a political environment that is not currently seen in any Arab country.(28)

Among the opportunities provided by the crisis in Iraq is Shia unification, particularly since their differences became obvious, and given the efforts of the Iranian sponsor to solve such differences. The threat posed by the Islamic State will force Shia groups to override their differences.(29) This could form the basis for rebuilding the Iraqi army on more ideological foundations so that a bigger role will be given to the al-Mahdi and Badr armies, the two forces that Maliki kept away from the Iraq army’s core leadership.(30)

Conclusion

There are a number of issues, factors and concerns that contribute to and direct Iranian policy internally as well as towards Iraq. All of these form elements of Iran’s key strategy, namely the Shia factor. Iran’s supreme interest was to ensure Shias grabbed power in Iraq. Since then, Shia and Kurdish elements have played a major role in formulating Iranian political and security strategy in Iraq. At the international level, it seems that Tehran sees current events in Iraq as an opportunity to exploit the “anti-terrorism” slogan to its benefit. Given that Iran cooperated with the US on Afghanistan under this umbrella, it could repeat this in Iraq, although cooperation with Washington has consequences that may make Tehran prefer to cooperate with Saudi Arabia instead.

Iran’s foreign relations with Iraq have always been and will remain influenced by political and security issues. Iraq has been Iran’s main competitor, and after it becomes stable once more, there are many factors that qualify Iraq to reconstitute a major challenge to Iranian national security in the region and to its political balance and strategic plans.

Iran’s strategy takes the form of practical realism, aiming to achieve and protect its interests in Iraq. This strategy is formulated taking into account the attitudes of regional and international competitors, changes in north Iraq and the power of Shias politically. Iran recognises that it is possible that Iraq will always pose a challenge to the Iranian national interest, and the Iranian strategy toward Iraq ranges between achieving security and creating opportunities.

__________________________________________________________

*Dr. Fatima al-Smadi is a researcher at AlJazeera Centre for Studies specialising in Iran.

Endnote:

1) Mandana Tishiyar and Mehnaz Thaheer Najad, Iraq’s Foreign Policy: Study of Political Geography, Role of Iraq and Neighbour relations, (Tehran: Mu’alifeen: 2005), 1.

2) Nasreen Jahangard, “Overview of Relations and Border Disputes Between Iran and Iraq”, History of Foreign Relations, 19 (Summer 2009): 104.

3) Kayhan Barzegar, Iran’s Foreign Policy in New Iraq, (Tehran, Strategic Studies Centre: 2007), 63.

4) Michael Eisenstadt, Michael Knights and Ahmed Ali, “Iran’s Influence in Iraq: Countering Tehran’s Whole-of-Government Approach”, Washington Institute for Near East Policy, Policy Focus #111 (April 2011), http://www.washingtoninstitute.org/uploads/Documents/pubs/PolicyFocus111.pdf and translated version at http://www.alukah.net/Translations/0/33138/#ixzz1odsJrOv .

5) This orientation is confirmed by Karim Sajjadpour, researcher at Carnegie Institute.

6) Iranian Diplomacy, Al-Maliki Substitute Must be Friend of Tehran, Iranian Diplomacy,1 July 2014, http://www.irdiplomacy.ir/fa/page/1935154/%D8%AC%D8%A7%DB%8C%DA%AF%D8%B2%DB%8C%D9%86+%D8%A7%D8%AD%D8%AA%D9%85%D8%A7%D9%84%DB%8C+%D9%85%D8%A7%D9%84%DA%A9%DB%8C+%D9%87%D9%85+%D8%A8%D8%A7%DB%8C%D8%AF+%D8%AF%D9%88%D8%B3%D8%AA+%D8%AA%D9%87%D8%B1%D8%A7%D9%86+%D8%A8%D8%A7%D8%B4%D8%AF.html .

7) Kayhan Barzegar, Iran and a New Iraq and the Political and Security System for the Persian Gulf, (Azad al-Islamiyah Da’irat al-Abhath, Tehran: 2008), 66.

8) Naseer Hassoun, “USD 12 Billion Trade Exchange between Baghdad and Tehran”, Al-Hayat Newspaper, 1 July 2014, http://alhayat.com/Articles/3322188/%D8%A8%D9%84%D9%8A%D9%88%D9%86-%D8%AF%D9%88%D9%84%D8%A7%D8%B1-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AA%D8%A8%D8%A7%D8%AF%D9%84-%D8%A8%D9%8A%D9%86%D8%A8%D8%BA%D8%AF%D8%A7%D8%AF-%D9%88%D8%B7%D9%87%D8%B1%D8%A7%D9%86 .

9) Eisenstadt, Knights and Ali, Iran’s Influence in Iraq: Countering Tehran’s Whole-of-Government Approach, 2011, http://www.washingtoninstitute.org/uploads/Documents/pubs/PolicyFocus111.pdf .

10) Ali Akbar Assadi, “Saudi Arabia and the Post-Saddam Iraq”, in Post-Saddam Iraq and Regional Actors, Center for Strategic Research, Research Bulletin #12 (April 2008), 80, http://www.csr.ir/departments.aspx?lng=en&abtid=05&depid=74&semid=275 .

11) Farhad Darvishi , “New Iraq and Iran’s Political Security Strategy”, Pishkesvat, 8 April 2011, http://pishkesvat.ir/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=172:1390-01-19-13-35-08&catid=1:report .

12) Ali Akbar Assadi, “Saudi Strategy Opposite”, New Iraq and Middle East Changes, page 11.

13) Tishiyar and Najad 2005, 99.

14) Ali Akbar Assadi 2008, 113, http://www.csr.ir/departments.aspx?lng=en&abtid=05&depid=74&semid=275 .

15) Ameer Abd Al Lahyan,”Relations between Iran and Iraq are Strategic and We Will Take Any Actions to Build a Strong and Unified Iraq”, Kayhan Newspaper, 2 July 2014, http://kayhan.ir/ar/news/3134/%D8%A7%D9%85%D9%8A%D8%B1%D8%B9%D8%A8%D8%AF-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%84%D9%87%D9%8A%D8%A7%D9%86-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B9%D9%84%D8%A7%D9%82%D8%A7%D8%AA-%D8%A8%D9%8A%D9%86-%D8%A7%D9%8A%D8%B1%D8%A7%D9%86-%D9%88%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B9%D8%B1%D8%A7%D9%82-%D8%A7%D8%B3%D8%AA%D8%B1%D8%A7%D8%AA%D9%8A%D8%AC%D9%8A%D8%A9-%D9%88%D9%86%D9%82%D9%88%D9%85-%D8%A8%D8%A7%D9%8A-%D8%A7%D8%AC%D8%B1%D8%A7%D8%A1-%D9%84%D8%A8%D9%86%D8%A7%D8%A1-%D8%B9%D8%B1%D8%A7%D9%82-%D9%82%D9%88%D9%8A-%D9%88%D9%85%D9%88%D8%AD%D8%AF .

16) Tishiyar and Najad 2005, 100.

17) Radio Algerie, Political Analyst Rasoul Thomson: For These Reasons, Turkey Opposes Independence of Iraqi Kurdistan Territories”, Radio Algerie, 2 July 2014, http://www.radioalgerie.dz/news/ar/article/20140702/5455.html .

18) Hassan Rouhani , “Why Iran Seeks Constructive Engagement”, Washington Post, 19 September 2013, http://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/president-of-iran-hassan-rouhani-time-to-engage/2013/09/19/4d2da564-213e-11e3-966c-9c4293c47ebe_story.html .

19) Hussein Mousavian, “Future of US-Iran Relations”, (Iranian-American Rapprochement: Future of Iranian Role Dossier), AlJazeera Centre for Studies, 6 April 2014, http://studies.aljazeera.net/files/iranfuturerole/2014/03/201433182148908794.html .

20) Ibid.

21) Al-Quds.com, “Khamenei Refuses American Intervention in Iraq and Accuses Washington of Exploiting Sectarian Disputes”, Jerusalem, 22 June 2014, http://www.alquds.com/news/article/view/id/510761 .

22) Orash Karmi, “Rouhani’s Advisor: Iran and US Can Put An End to Iraq Crisis”, Al-Monitor, 15 June 2014, http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/ar/originals/2014/06/iraq-crisis-end-iran-us-rouhani-adviser.html#ixzz36gJDSztk .

23) Kayhan Barzegar, “Geopolitical Aspect of Extremist Currents Threaten Iran’s National Security”, roundtable proceedings from Moderation and Extremism: Iran in the Region, Tehran, 23 June 2014, http://www.shafaqna.com/persian/elected/item/77667-%DA%A9%DB%8C%D9%87%D8%A7%D9%86-%D8%A8%D8%B1%D8%B2%DA%AF%D8%B1-%D8%AC%D9%86%D8%A8%D9%87-%DA%98%D8%A6%D9%88%D9%BE%D9%84%DB%8C%D8%AA%DB%8C%DA%A9-%D8%AC%D8%B1%DB%8C%D8%A7%D9%86-%D9%87%D8%A7%DB%8C-%D8%A7%D9%81%D8%B1%D8%A7%D8%B7%DB%8C%D8%8C-%D8%A7%D9%85%D9%86%DB%8C%D8%AA-%D9%85%D9%84%DB%8C-%D8%A7%DB%8C%D8%B1%D8%A7%D9%86-%D8%B1%D8%A7-%D8%AA%D9%87%D8%AF%DB%8C%D8%AF-%D9%85%DB%8C-%DA%A9%D9%86%D8%AF.html .

24) Ibid.

25) David Ignatius, “Iran Overplays its Hand in Iraq and Syria”, Washington Post, 3 July 2014. http://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/david-ignatius-iran-overplays-its-hand-in-iraq-and-syria/2014/07/03/132e1630-02db-11e4-8572-4b1b969b6322_story.html .

26) Iran News Agency, “Funeral in Shiraz for Martyr Defending Shia Holy Sites”, Iran News Agency, 5 July 2014, http://www.irna.ir/fa/News/81225247/%D8%A7%D8%AC%D8%AA%D9%85%D8%A7%D8%B9%DB%8C/%D9%BE%DB%8C%DA%A9%D8%B1_%D9%85%D8%B7%D9%87%D8%B1_%DB%8C%DA%A9_%D8%B4%D9%87%DB%8C%D8%AF_%D9%85%D8%AF%D8%A7%D9%81%D8%B9_%D8%AD%D8%B1%D9%85_%D8%AF%D8%B1_%D8%B4%DB%8C%D8%B1%D8%A7%D8%B2_%D8%AA%D8%B4%DB%8C%DB%8C%D8%B9_%D8%B4%D8%AF .

27) Karim Sajjadpour, “The Arab World is Strategically Paralyzed”, roundtable proceedings from Moderation and Extremism: Iran in the Region, Tehran, 23 June 2014, http://www.shafaqna.com/persian/elected/item/77665-%D8%AF%DA%A9%D8%AA%D8%B1-%D8%B3%D8%AC%D8%A7%D8%AF%D9%BE%D9%88%D8%B1-%D8%AF%D9%86%DB%8C%D8%A7%DB%8C-%D8%B9%D8%B1%D8%A8-%D8%AF%DA%86%D8%A7%D8%B1-%D9%81%D9%84%D8%AC-%D8%A7%D8%B3%D8%AA%D8%B1%D8%A7%D8%AA%DA%98%DB%8C%DA%A9-%D8%B4%D8%AF%D9%87-%D8%A7%D8%B3%D8%AA.html .

28) Ibid.

29) Development and Security Institute, “Geopolitics of the Crisis in Iraq”, Development and Security Institute, 21 June 2014, http://idsp.ir/fa/pages/?cid=12922.

30) Ibid.