Whether narratives between the parties to any crisis are exchanged as limited negative interaction or lead to a protracted conflict, they represent the key to any process of deconstructing the nature of the disputed issues, or deep-rooted causes, especially during the rush to escalation and deepening the artificial dichotomy between ‘we’ and ‘they’. They also tend to imply an even judgement system by drawing a line of demarcation between ‘our virtues’ and ‘their vices’. Accordingly, each party seeks to construct a political discourse based on some subjective claims, rather than an objective account of facts, with the hope of monopolizing ‘legitimacy’ and positioning the Self on ‘moral’ high ground. Narrative analysis scholars have argued for three mutually supporting ideas that form the underpinning: a. that moral values and ethics are relative; b. that what is important is the kind of behavior and attitudes that makes for the harmonious functioning of the group; and c. that the best way to achieve this is through the application of “scientific” techniques. (1)

From the onset of the Gulf Crisis, the pace of escalation by the new Quartet [United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain and Egypt] against Qatar increased right after US President Donald trump wrote in his famous tweet June 6, 2017, “during my recent trip to the Middle East I stated that there can no longer be funding of radical ideology. Leaders pointed to Qatar – look!” Direct accusations increased against Qatar, including harboring ‘terrorists’ in reference to some members of the Palestinian Hamas movement and the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood. Trump’s tweet seemed to be a moment of hyper-politics by putting his thumb on the scale in Saudi Arabia's favor. Meanwhile, the Pentagon was praising Qatar for its “enduring commitment to regional security”, and for hosting US forces in Al-Udeid base. While addressing a question from journalists in Washington on whether Qatar supported terrorism, the Pentagon spokesman, Capt. Jeff Davis, said he was not qualified to answer, “I consider them a host to our very important base at al-Udeid.” (2)

This paper examines the transformation of Trump’s position, the Quartet’s narrative, and Qatari counter-narrative after one year; and traces the possibility of de-escalation shift along Washington’s pursuit of mediation in the context of the initial framework of Kuwaiti intervention.

Tracing the Early Rift

Riyadh summit held May 20, 2017 was the first international platform for Trump to articulate his foreign policy vision, four months after delivering his inauguration speech at the footsteps of the US Capitol in Washington. While addressing fifty Arab and Muslim leaders in Riyadh, he sought to naturalize his discourse of ‘radical Islamic terrorism’, a main pillar of his electoral campaign, in a public forum near Mecca and Medina, the two holly sites of Islam. He stated, "Perhaps this [Summit] will be the beginning of the end to the horror of terrorism!" He also implied subtle incrimination against Qatar, “So good to see the Saudi Arabia visit with the King [Salman] and 50 countries already paying off. They said they would take a hard line on funding extremism and all reference was pointing to Qatar. Perhaps this will be the beginning of the end to horror of terrorism!” (3)

With the exception of Qatar, the Summit attendees developed a dilemma of groupthink, which has led to an overcapitalization in Trump's ego and future policies by the Emiratis, the Saudis, the Bahrainis, and their allies. The mutual fear of Iran and political Islam, energized by a hard-power-based framework of counterterrorism, seems to have blocked critical thinking about the feasibility of Trump's grandiose promise of eradicating the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL, known as ISIS) and other forces of extremism in the region. Trump also told his Arab and Muslim audience that “America is committed to adjusting our strategies to meet evolving threats and new facts. We will discard those strategies that have not worked—and will apply new approaches informed by experience and judgment. We are adopting a Principled Realism, rooted in common values and shared interests.” (4)

The truth of Trump’s claimed “Principled Realism” was tested immediately by the Gulf Crisis when he decided to support the Quartet’s political and economic blockade on a country that relies on importing most of its food needs by land mainly through Saudi Arabia. Ilan Goldenberg of the Centre for a New American Security believes "the president has thrown fuel on the fire. If we are going to build a coalition to fight extremism you have to smooth over differences and this is going to inflame them." (5) There was some ironic contrast between Trump’s position toward the US-Saudi coordination, along their mutual interests, and the stance of US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson who implied reasonable compromise between the pragmatism of his country’s strategic interests and the moral call for preventing a political crisis from shifting into a humanitarian disaster. Tillerson cautioned against the "humanitarian consequences" of Qatar blockade, which hinders the United States' military efforts. He told reporters at the State Department that Washington expected the Gulf States to "immediately take steps to de-escalate the situation and put forth a good faith effort to resolve the grievances they have with each other." (6)

The divergence between Trump’s tweets and Tillerson’s statements energized the battle of narratives and counter-narratives over Qatar’s policies in the regional context. The Quartet States decided to penalize Doha for not going along with their animosity against Iran, ant not stigmatizing Hamas and the Brotherhood with the label of ‘terrorist’. For years, Qatar’s political discourse and Aljazeera’s impact on the Arab public opinion, before and during the 2011 uprisings, have irritated most Gulf and other Arab governments. Another factor is Doha’s growing soft power and successful interventions in several international conflicts, including the release of several members of Taliban from Guantanamo prison, Sudan conflict, Hamas-Fatah embattlement, and various peacebuilding projects in Asia, Europe, and Africa. Some area experts have realized that “the root cause of the current crisis lies much deeper. What has driven a wedge between the two fronts, is a fundamental philosophical disagreement over values, narratives and worldviews,” as wrote Andreas Krieg in recent book “The Socio-Political Order and Security in the Arab World: From Regime Security to Public Security”. (7)

Full Speech by Rex Tillerson on the Gulf diplomatic crisis [video]

Some observers of Beltway politics have pointed to a possible blind spot in Trump’s overall calculation, since he overestimated the US-Saudi relations; and whether the Saudi leadership still has the same political influence in the region. In his New York Times op-ed “President Trump’s Arab Alliance Is a Mirage”, Antony J. Blinken, Director of the Penn Biden Center for Diplomacy and Global Engagement and former Deputy Secretary of State argues that “Trump’s unconditional support for the Saudis during that same visit also seemed to embolden them to not just break relations with, but also impose an economic blockade on, Qatar. His tweets taking credit for the move left the Qataris reeling. If all of this seems confusing, consider this: the Trump administration says it wants to create a military coalition of Arab states, led by Saudi Arabia, to fight Islamist terrorism. It was as if Mr. Trump was trying to break his own alliance, described as an “Arab NATO,” before it had even formed.” (8)

In a previous analytical piece, I wrote, “Trump's speech in Riyadh played well to the Gulf leaders' frustration with the Obama administration's Iran policies and their irrational fear of the Iranians. Trump's presence was instrumental in emboldening the reconstructivism of a "common" enemy in the region.” (9) Consequently, a new cold war emerged behind the façade of the presumed Gulf unity, and media narratives became the gateway of the Quartet-Qatar dichotomy. In Washington, the Emirati ambassador, Yousef al-Otaiba, has been ambitious in his anti-Qatar public relations campaign. He often reiterated UAE’s complaints about Qatar's maverick foreign policy, "What is true is Qatar's behavior. Funding, supporting, and enabling extremists from the Taliban to Hamas ... Inciting violence, encouraging radicalization, and undermining the stability of its neighbors." (10)

The once brotherly weness [from we] and cozy tribal connections across most Gulf societies became entangled in a complex web of radicalized narratives through both traditional media and social media. According to Sara Cobb, a leading conflict practitioner of narrated conflict resolution, “radicalized narratives reduce the possibility for reflective judgements and obviate the possibility of a political moment; although this frame does not describe the narrative conditions (process and content) that could generate subjectification or reflective judgements, it does create a theoretical link between the nature of narrative and the critical dynamics in the public sphere.” (11) More than any other new media platform, Tweeter has served the new Gulf war of narratives per excellence. One Arab commentator captured how the media discourse has “polluted the Gulf sky” since June 5, and “increased the cruelty and injustice of the political procedures that have harmed the peoples of the region.” (12)

Interpretive Value of the Narrative Game

Narrative analysis represents the most recent tool of deconstruction in social sciences. It provides a reliable approach to “understanding how and why people talk about their lives as a story or a series of stories. This inevitably includes issues of identity and the interaction between the narrator and audience(s).”(13) In the last two decades, there has been growing interest in what can be termed as the interpretive turn or interpretive movement. In their book “Storied Lives: The Cultural Politics of Self-Understanding”, George C. Rosenwald and Richard L. Ochberg explain how narrative analysis disrupts the traditional social scientific analysis, which has realist assumptions and a focus on information collection. Instead the focus shifts to look at the very construction of narratives and likewise the role they play in the social construction of identity.” (14)

Narrative analysis helps also develop nuanced understanding of the context and trajectory of tweets, speeches, and other types of political statements around the Gulf Crisis. It reveals both constructivism and truth relativism of how each interlocutor articulates his or her self-positioning. Rosenwald and Ochberg argue that the use of a narrative analysis approach with its focus on the social construction of the story “means that uncovering the ‘truth’ no longer becomes the object of analysis; there has been a move away from the ‘what’ to the ‘how’. This in turn deconstructs the realist position that assumes that life stories can be regarded as ‘mirrors of life events’.” (15)

The narratives that have pivoted around the Gulf Crisis, so far, have ushered to latent conformity, or what sociologist Ken Plummer calls symbolic interactions and political process, in joint actions involving three groups of people: the producers [Quartet States], the coaxers [Trump and other sympathizers] and the consumers [world public opinion]. (16) As Sarah Earthy and Ann Cronin point out, “To claim that stories can be understood as political process alerts us to the power mechanisms or structures that permit certain stories to be told while silencing others.” (17)

One cannot underestimate the political significance and trajectory of those narratives in reshaping Gulf politics. The Saudi and Emirati efforts to curb the Qatari-Iranian rapprochement and to undermine political Islam imply more ironies in the Gulf’s regional and international relations. Steven Cook of the Council on Foreign Relations explains that “Such is the nature of the Middle East that while it is entirely true that the Qataris are difficult partners and pursue unsavory policies, that does not make them all that different from any of Washington’s other Middle Eastern allies. All of these countries have questionable records on human rights, and some have distinguished themselves as incubators of extremism. People who live in glass houses should not throw stones, except that's exactly what happens in the Middle East." (18)

Groupthink Dilemma

The derailment of conflict into escalation often leads to an exchange of negative narratives and damaging perceptions. It also generates mutual dark images as has been the case of the Gulf Crisis, between the disputing parties; and ultimately energizes the construction of ‘Other’ who was until recently a part of the collective ‘Self’ within the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC). The widespread groupthink, echoed among the four capitals of the Quartet, has helped the stigmatization of the new ‘Other’, and opened the door for a variety of pretenses and justifications to target its status and reputation and destroy its economic, political, and diplomatic capabilities. Unfortunately, the dominance of self-centered realist and interest-oriented assumptions has led to the implosion of the GCC.

Groupthink can be defined as a “mode of thinking that persons engage in when concurrence-seeking becomes so dominant in a cohesive in-group that it tends to override realistic appraisal of alternative courses of action.” (19) By using the analytical tools of social psychology, groupthink derives its appeal as a collective psychological episode among members of a group leaning toward some form of agreement or harmony in opinion, and may lead to some illogical outcome or a malfunction if the decision-making process. One of the early theorists of the concept groupthink William Whyte Jr. wrote in 1952: “We are not talking about mere instinctive conformity — it is, after all, a perennial failing of mankind. What we are talking about is a rationalized conformity- an open, articulate philosophy which holds that group values are not only expedient but right and good as well.” (20)

There was an apparent double jeopardy of the groupthink dilemma between the Riyadh Summit, which took place April 20 and 21 and the Gulf Crisis June 5. The mutual fear of Iran and political Islam, energized by a hard-power-based framework of counterterrorism despite the unsettled definition of ‘terrorism’ after seventeen years of the ‘War on Terror’ paradigm, resentment of Aljazeera’s progressive discourse have blocked critical thinking about the feasibility of exterminating Qatar as well as Trump’ miscalculation of siding with the Saudis.

On Capitol Hill, several Congressmen expressed concern over Trump's position vis-a-vis the Gulf conflict. Ruben Gallego (D-AZ), a member of the House Armed Services Committee, sharply criticized Trump's statement; "This situation is complex, like many diplomatic situations, and showcases how uniquely unqualified Donald Trump is in securing the best interests of the United States when it comes to foreign policy and national security."(21)

|

| [Al Jazeera] |

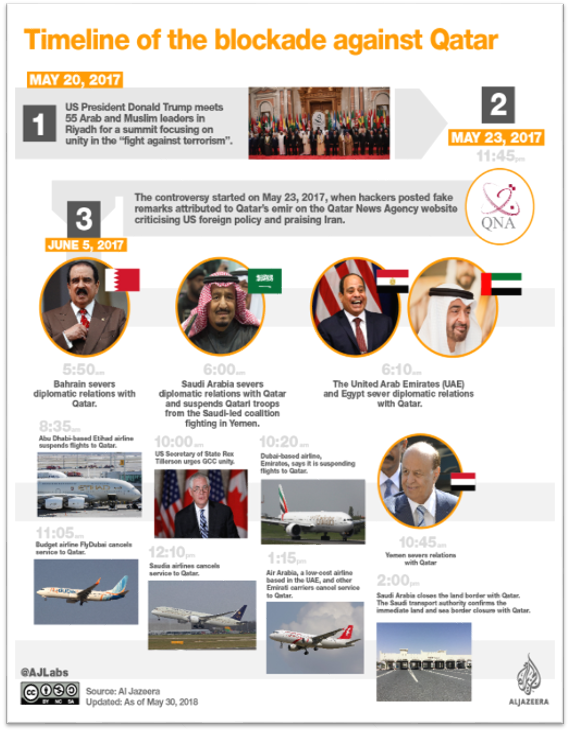

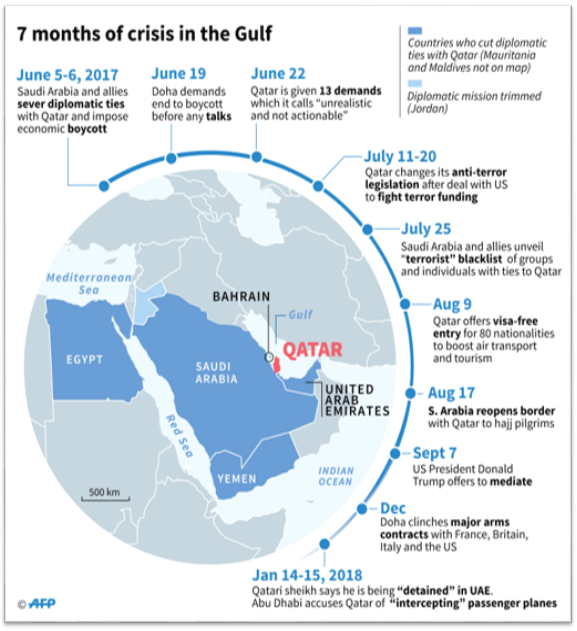

Timeline of the Gulf Crisis

There has been a dominant linear view of the Crisis that advocates considering an open-ended political dilemma that continues on the same pace of complexity of June 5, 2017 in the context of the tacit US-Quartet agreement on demonizing Qatar. However, the use of narrative analysis helps differentiate between four different phases, either in light of the Quartet’s main reasons of the blockade, Qatar’s approaches of containing and managing the Crisis, or the possible ways of ending the conflict.

The following chart the time framework and type of interaction across four phases: 1) compatibility on the isolation of Qatar; 2) policy of containment; 3) the Kuwaiti factor; and 4) the White House’s consolidation of the Kuwaiti mediation.

|

May 20 – June 5, 2017 Compatibility on the Isolation of Qatar |

|

|

June 5 – September 7, 2017 Policy of Containment

|

|

|

September 7, 2017 – March 5, 2018 The Kuwaiti Factor |

|

|

March 5 – End of May 2018 The White House’s Consolidation of the Kuwaiti Mediation |

|

The Gulf Crisis has entered another year of divergent expectations among the parties. Any formula of settlement, or positive transformation, remains dependent on a web of dialectical conjunctions: a) dialectic of non-declared political positions behind the scenes; b) dialectic of public narratives circulating across traditional and new media, namely Tweets, which has perpetuated the psychological and political rift behind the virtual reality screens of computers as cellphones; and c) dialectic of the new US-Iranian escalation. Secretary of State Pompeo has publicized the twelve-demand list for Tehran, and waged what amounts to a trade war against the European corporations and governments that have invested in the Iranian market since the signature of the nuclear deal in June 2015. Accordingly, this complexity has shaped the battle of narratives.

1. The Narrative of Dictating Quartet’s Demands

There is a fine line between objective understanding and subjective interpretation of the causality of the Gulf Crisis. Accordingly, the world public opinion was divided into two camps: the first supports the Quartet’s blockade and the subsequent 13-demand list issued in the second week of July 2017.

|

1 |

Scale down diplomatic ties with Iran and close the Iranian diplomatic missions in Qatar, expel members of Iran's Revolutionary Guard and cut off military and intelligence cooperation with Iran. |

|

2 |

Immediately shut down the Turkish military base, which is currently under construction, and halt military cooperation with Turkey inside of Qatar. |

|

3 |

Sever ties to all "terrorist, sectarian and ideological organizations," specifically the Muslim Brotherhood, ISIL, al-Qaeda, Fateh al-Sham (formerly known as the Nusra Front) and Lebanon's Hezbollah. |

|

4 |

Stop all means of funding for individuals, groups or organizations that have been designated as terrorists by Saudi Arabia, UAE, Egypt, Bahrain, US and other countries. |

|

5 |

Hand over "terrorist figures", fugitives and wanted individuals from Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Egypt and Bahrain to their countries of origin. |

|

6 |

Shut down Al Jazeera and its affiliate stations. |

|

7 |

End interference in sovereign countries' internal affairs. Stop granting citizenship to wanted nationals from Saudi Arabia, UAE, Egypt and Bahrain. |

|

8 |

Pay reparations and compensation for loss of life and other financial losses caused by Qatar's policies in recent years. The sum will be determined in coordination with Qatar. |

|

9 |

Align Qatar's military, political, social and economic policies with the other Gulf and Arab countries, as well as on economic matters, as per the 2014 agreement reached with Saudi Arabia. |

|

10 |

Cease contact with the political opposition in Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Egypt and Bahrain. |

|

11 |

Shut down all news outlets funded directly and indirectly by Qatar, including Arabi24, Rassd, Al Araby Al Jadeed, Mekameleen ,and Middle East Eye, etc. |

|

12 |

Agree to all the demands within 10 days of list being submitted to Qatar, or the list will become invalid. |

|

13 |

Consent to monthly compliance audits in the first year after agreeing to the demands, followed by quarterly audits in the second year, and annual audits in the following 10 years. |

The Quartet’s List of 13 Demands [Complied by the author]

|

|

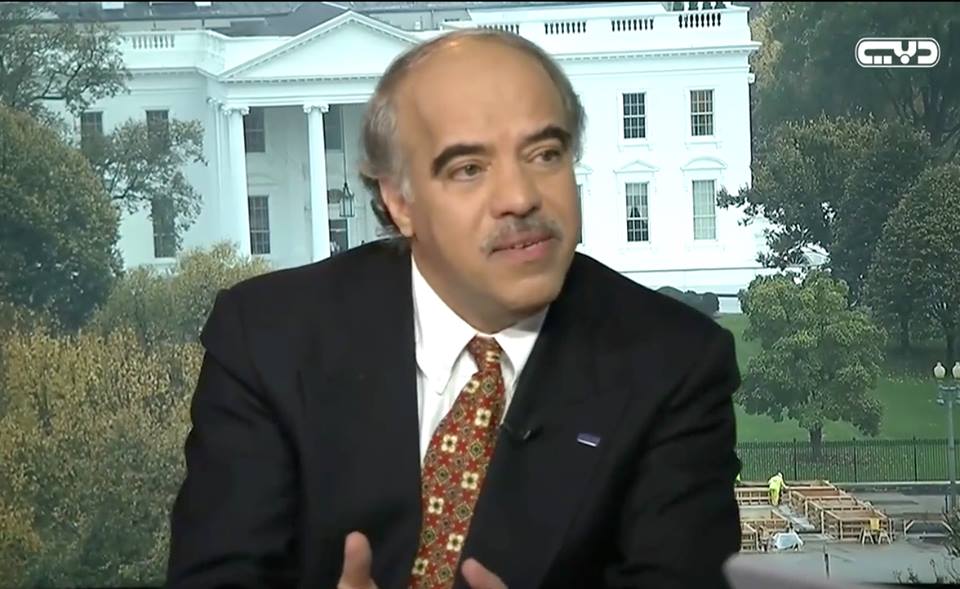

Ambassador Yousef Al Otaiba addressing the Washington-based Center for Strategic and International Studies [CSIS AP] |

Three weeks before the list was leaked to the media, Tillerson implied some skepticism about the extent of what the Quartet expected from Qatar; "We hope the list of demands will soon be presented to Qatar and will be reasonable and actionable.” (22) The list included a mix bag of demands that apparently oversighted the principle of state sovereignty and other imperatives of international law. As one commentator put it, it was not a “question of demands, but an insult. The tone of these demands and the underlining approach does not only show total ignorance of international relations and a lack of understanding about what state sovereignty means, but it also goes to the heart of a lack of coherence and preparation by the four countries over putting a document like this together.” (23)

By July 19, 2017, the Quartet’s strategy shifted from thirteen “demands” to six “principles” which the four-nation alliance against Qatar framed as the parameters for future talks on how the resolution can proceed.

|

1 |

Commitment to combat extremism and terrorism in all its forms and to prevent their financing or the provision of safe havens |

|

2 |

Prohibiting all acts of incitement and all forms of expression which spread, incite, promote or justify hatred and violence |

|

3 |

Full commitment to Riyadh Agreement 2013 and the supplementary agreement and its executive mechanism for 2014 within the framework of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) for Arab States |

|

4 |

Commitment to all the outcomes of the Arab-Islamic-US Summit held in Riyadh in May 2017 |

|

5 |

To refrain from interfering in the internal affairs of States and from supporting illegal entities |

|

6 |

Responsibility of all States of international community to confront all forms of extremism and terrorism as a threat to international peace and security |

extremism and terrorism as a threat to international peace and security

The Quartet’s Alternative List of 6 Principles [Complied by the author]

Officials from the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain and Egypt spoke to journalists at the United Nations July 19 in an attempt to sustain their pressure on Qatar. Emirati ambassador to the UN Lana Nusseibeh maintained that “We’re never going back to the status quo,” said during the briefing on Tuesday. That needs to be understood by the Qataris.” One can argue that there an early indicator of relative disparity between the Emirati and Saudi new positions. For instance, Saudi ambassador at the United Nations Abdallah Al Mouallimi said “we are all for compromise, but there will be no compromise on these six principles.” He added it “should be easy” for Qatar to agree to the six principles, which are similar to the Riyadh agreements signed by the Qatari emir, Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad Al Thani, in 2013 and 2014. One of the principles is an explicit call for Doha to abide by those agreements. (24)

The Quartet’s shift from a 13-demand list a six-‘principle’ list had mixed reactions. Some interpretations contested the notion that the Quartet’s position has weakened in a matter of a few weeks. Mohammed Al-Yahya, a Saudi analyst of Gulf politics and non-resident fellow at the Atlantic Council, does not see it as “a softening of the quartet's position on Qatar per se, as much as a measure taken to restart the negotiation process. It is clear that the boycotting nations are prepared to play the long game with Qatar, but there is no doubt that a speedy resolution of the crisis will be in everyone's interest… These six principles are best viewed as an effort to set the foundation for meaningful negotiation process.” (25) Other views have acknowledged the non-feasibility of the original 13-demand list. Brian Katulis, a Middle East policy expert at the Center for American Progress, was not surprised since “there are more voices in all of these countries calling for a more pragmatic step back from the demands which were so maximalist and presented in such a way that makes it hard for Qatar to accept.” (26)

|

| [AFP] |

The Quartet States implied a realist discourse of power and alliance against a small nation in the neighborhood while assuming Trump and the rest of the US administration would back up their plans. Bahrain’s foreign minister, Shaikh Khalid Bin Ahmad Al Khalifa, representing the kingdom at the conference in Kuwait late May 2017, said that questions about the end of the crisis should be addressed to Qatar; “the ball is in their field.” (27) Similarly, Saudi Arabia’s foreign minister Adel Al Jubeir has reiterated his position that Qatar should transform “from a state of denial to a state of realization of the current situation it is living.” He told his audience during a lecture at the Egmont Institute in Brussels February 23, 2018 that “the Qatar crisis is a small one compared to important issues in the region, and all we want is for [Doha] to stop using their media platforms to propagate hatred… Even though Qatar has signed agreements to stop supporting terrorism that has still not completely happened.” (28)

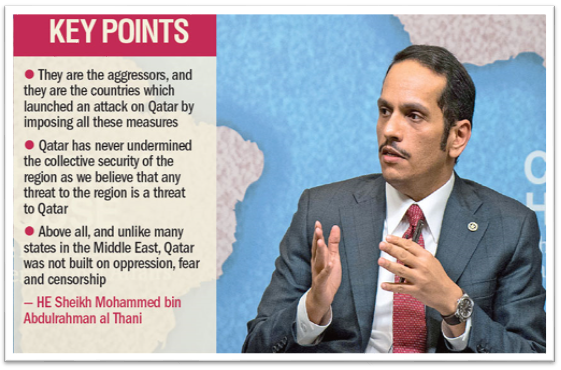

2. The Narrative of Contesting Quartet’s Demands

As the famous Newtonian motto goes, “for every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction.” The alleged charges of ‘supporting’ terrorism did not resonate with numerous analysts and large segments of the world public opinion. Some observers questioned the motivation of the charges against Qatar while the majority of the 9/11 attackers came from Saudi Arabia. To many, the dispute in the Gulf “amounts to the pot blaming the kettle and twisting the truth to serve rival narratives,” as commented one Gulf analyst. (29)

Others rejected the immorality of the Quartet’s land and air blockage of Qatar as an infringement of the humanitarian international law. Several demonstrations took to the street in Switzerland, Germany, and France in protest of Qatar blockade. Sara Pritchett, spokesperson for EuroMed, a human rights organization, condemned the shortage of essential medical equipment and medicines that were not reaching Qatar. As she stated, "The UAE have been a key player in the blockade, and their actions have had a special impact on medicine, commercial trade and separation of families, just to name a few.” (30) In mid-February, Qatar's National Human Rights Committee reported that the Louvre museum apologized and opened an official inquiry into the incident where Abu Dhabi's Louvre Museum map omitted the Qatari Peninsula.

|

| [Getty Images] |

Two weeks into the crisis, the State Department spokeswoman, Heather Nauert, expressed skepticism toward the Quartet states for not baking up their charges against Qatar. “Now that it has been more than two weeks since the embargo has started, we are mystified that the Gulf States have not released to the public nor to the Qataris the details about the claims they are making toward Qatar.” Nauert also raised doubts about the real causes of the animosity toward Qatar; "at this point, we are left with one simple question: Were the actions really about their concerns regarding Qatar's alleged support for terrorism or were they about the long-simmering grievances between and among the GCC countries," in reference to the Gulf Cooperation Council. (31)

The Quartet’s narratives have sought diligently to construct a dubious image of Qatar as a local enemy. A virtual echo chamber emerged between Abu Dhabi, Riyadh, Manama, and, to some extent, Cairo. The anti-Qatar charges coming from different directions have sustained each other as the growing tide of a turbulent ocean. However, these narratives have implied more than a dilemma of an echo chamber.

Any U Turn?

Narratives and counter-narratives sometimes exhaust their radical escalatory tone and demonization of the ‘enemy’ at the intersection between political and media-oriented discourses. They can be useful also in detecting any possible positive shift and any degree of political rapprochement between the parties. The tone and trajectory of their narratives can indicate whether they would be willing to consider a framework of negotiated settlement, or a possible formula of reconciliation, after the escalation phase runs out of steam or the parties feel bored with a long stalemate. Rami G. Khouri, professor of journalism at the American University of Beirut and senior fellow at the Harvard Kennedy School Middle East Initiative, wrote that in the court of global public opinion, “the Qataris appear to be much more sensible, consistent, focused, and precise”. In contrast, “the Saudi-Emirati-led states seem to express genuine anger and fear accompanied by unrealistic and unreasonable demands, but without convincing evidence for their accusations.” (32)

However, the first thirteen months of the Gulf Crisis have not shown any tangible indicators of flexibility or willingness to settle the conflict. Trump has made more than six phone calls with Gulf leaders. Tim Lenderking, the top State Department official for the Gulf region, and retired Marine Corps. Gen. Anthony Zinni have made more than one trip to Gulf capitals since February. During then-newly-appointed Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s visit to Riyadh April 27, 2018, the New York Times captured the zest of his message to the Saudis over his two-day talks in a bold title, “Pompeo’s Message to Saudis? Enough Is Enough: Stop Qatar Blockade”. The paper revealed that Pompeo went to Riyadh to deliver the same message “Stop” to Mr. Jubeir, to Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, and to King Salman. It explained the reasons for such a surprising US position ten months into the crisis; “confronting Iran, stabilizing Iraq and Syria, defeating the last of Islamic State, and winding up the catastrophic civil war in Yemen are seen in Washington as increasingly urgent priorities that cannot be fully addressed without a united and more robust Arab response.” (33)

As of this writing, the US-Gulf summit has been postponed until September 2018 with no apparent political momentum over summer, which would solidify its feasibility, let alone its success. Mehran Kamrava, director of the Center for International and Regional Studies at Georgetown University in Doha, has argued for compromise. He emphasized, “We need to change the narrative of us versus them. You can pick your friends, but you cannot pick your neighbors. This logic also applies to the GCC crisis because so far, the possibility of devising a scenario outside of the zero-sum game approach has largely been ignored. Collective security agreements work best when everyone contributes and recognizes its neighbors’ right to exist.” (34)

The diplomatic contacts continue between Washington, and Riyadh and Abu Dhabi on the one hand, and Doha on the other, after a missed window of opportunity in February 2018, the peak of the White House’s mediation efforts. Since then, the narratives that have circulated around the crisis have highlighted some irony: an asymmetrical contrast between the stagnation and apparent lack of interest in settling the crisis among the parties themselves, especially UAE, whereas Washington has shown a pragmatist approach toward ending the crisis as soon as possible. Trump did relinquish his willingness to “be the mediator”, while he expressed his appreciation and respect of the [Kuwaiti] mediation”, as he told the visiting Emir of Kuwait back in September 2017. He stated then during their joint news conference, “If I can help mediate between Qatar and, in particular, the UAE and Saudi Arabia, I would be willing to do so. And I think you’d have a deal worked out very quickly.” (35)

|

| [Al Jazeera] |

Washington’s attachment to an immediate settlement of the Gulf Crisis is based on a strategic foreign policy vision constructed initially by Secretary Tillerson, and adopted by President Trump a few months after Tillerson was dismissed from his position. During the US-Qatari Strategic Dialogue meeting in Washington January 30, Tillerson stated, “It is critical that all parties minimize rhetoric, exercise restraint to avoid further escalation, and work toward a resolution. A united GCC bolsters our effectiveness on many fronts, particularly on … countering terrorism, defeating ISIS, and countering the spread of Iran’s malign influence.” (36)

This diplomacy of mediation has been a common vision of both outgoing and incoming secretaries of State, Tillerson and Pompeo, as well as Deputy Secretary of State, John J. Sullivan. The latter “emphasized the United States’ desire to resolve the Gulf dispute and his hope that all parties will engage constructively ahead of the U.S.-GCC Summit later this year,” during his meeting with Saudi Foreign Minister al-Jubeir at the G-20 foreign ministers’ meeting in Buenos Aires late May. (37)

The Crisis Narratives at New Intersections

A close analysis of the dynamic rivalry of narratives helps reveal three sub-circles of transformation. First, the outcome of the debate between Trump and the political establishment in Washington. Second, the transformation of the subjective interpretation of certain stakeholders, namely Saudi Crown Prince Mohamed Bin Salman, between driving the escalation momentum against Qatar in June 2017 and his new statements in Cairo in February 2018. Third, the adjustment of Qatar’s image and regional role in the context of the US-Qatari Strategic Dialogue held in Washington.

1. Institutional Trump, Not Unruly Trump

President Trump has ultimately avoided the gap that existed vis-à-vis the political establishment, and embraced the vision of then-Secretary of State Tillerson, Defense Secretary Mattis, and other senior officials in Washington. It remains the very framework that Pompeo has urged Gulf capitals to consider and bypass the discourse of demands between Abu Dhabi, Riyadh, and Doha. Both Quartet’s list of 13-demands and the second six-principle list no longer come up to the surface in any settlement talks brokered by the United States without overpassing the Kuwaiti framework of mediation.

Trump has also sought to dispel the perception that he was inclined to support the Saudi-Emirati position by charging Qatar with alleged support of” terrorism" during the Riyadh summit. In the tenth month of the crisis, Trump hosted the Emir of Qatar at the White House, and stated that the United States and Qatar "have been great friends in so many ways" and "are working very well together… We are working on unity in that part of the Middle East and I think it's working out very well; there are lot of good things happening." (38) After the meeting, the White House issued a statement saying President Trump had expressed his thanks to the Emir of Qatar for his country's continued commitment to combating the financing of terrorism and extremism. Trump’s change of position, after he was briefed on the results of the shuttle mission of Anthony Zinni and Timothy Lenderking in the Gulf in February, reflects three important things in the White House’s diplomatic steps toward settling the Crisis along the Kuwaiti mediation:

First, Trump believes that determining the American role in resolving the Gulf crisis implies an a careful assessment of the nature and trajectory of the conflict, and the parties’ declared and undeclared goals. It also requires not rushing to demonize any party for the benefit of the other, or cognitive or political positioning in favor a particular escalatory discourse by any party or parties that has sought to drag the White House into some misjudgment at the beginning of the Crisis. This shift explains why Trump departed from his previous position, and decided to come closer to an alternative strategic position supported by the political establishment, including members of Congress.

Second, Trump’s desire to restore his credibility in the eyes of all Gulf nations and to go beyond the charges of the possibility that the Emirati money managed to buy some political leverage in the White House through his cozy contacts with some dealmakers and shakers such as George Nader and Elliot Broidy. Rami Khouri points to the fact that “the Saudi-Emirati media propaganda pushing such accusations has been embarrassing in its ultra-thin doses of truth, and wildly counter-productive, serving only to further damage the credibility that some GCC media did enjoy in recent years. (39)

Third, Trump's explicit commitment to ending the Gulf conflict can imply signs of some undeclared shifts in the positions of some parties to the conflict. They have reinforced his current level of optimism about some relative rapprochement between the Gulf capitals awaiting the expected Gulf-US summit late summer.

2. Bin Salman and Riyadh’s Flexible Position

In the early weeks of the crisis, the Emirati and Saudi discourse, backed by Manama and Cairo, was forceful in demonizing Qatar, and compiling charges of ‘financing terrorism’ and ‘harboring’ and ‘supporting’ terrorist organizations. Doha responded with a non-emotional and non-escalatory discourse, and demanded the Quartet to present any evidence to prove those charges. Rami Khoury recalls how “the Saudis-Emiratis have maintained a very impressive demeanor of confidence, strength, determination, patience, and a willingness to punish Qatar severely, and for years, for its alleged transgressions in supporting terrorism and threatening their security. Their problem with this display of political bravado is that nobody else buys it, and they are awkwardly isolated in their tent woven of threads of bravado.”(40)

Since March 2018, there have been new signs of a short-lived groupthink between the Emirati and Saudi discourses. Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s recent statement does not echo what Abu Dhabi had planned in the first six months of the Crisis. One indicator of this shift was his statement before a number of Egyptian journalists in Cairo, “I do not occupy myself with it. The one handling the matter has a post less than a minister’s. Qatar’s entire population is less than the number of residents in a street in Egypt. Any minister (in Saudi Arabia) can resolve that crisis… "A dear colleague at the ministry of foreign affairs whose ranking is Grade 12 is in charge of the Qatari matter, in addition to the tasks assigned to him,” he said.

|

| Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed Bin Salman [Getty] |

It is not difficult for an average person, let alone a political psychologist, to discover that minimizing or diminishing the importance of the Crisis at this stage suggests that the Saudi Crown Prince may be looking for a decent way out of the Crisis, without losing face or appearing to be making concessions. Probably, Riyadh and Washington are seeking an adequate scenario to safeguard his political face unlike other hawkish stakeholders who have trumpeted the isolation of Qatar. As a US official said in Washington, President Trump and Prince Mohammed bin Salman discussed the crisis amid "new developments that promote further discussions.”

It seems that the transformation of these narratives and the volatility of the political discourse between the Gulf capitals have contributed to the crystallization of a new equation that has shined in the eyes of Trump who has been keen on bypassing the differences of the Gulf. The equation can been imagined in the form of a triangle:

First, the position of Doha, which Trump considers "committed to contributing to the restoration of the GCC unity and the need to put an end to the conflict," as said the White House statement. This position appears to be a source of satisfaction for Trump and facilitates his efforts to end the Crisis.

Second, from a psychological and political perspective and media content analysis, the position of Riyadh appears to be gradually moving away from the escalation discourse. The phone call between President Trump and King Salman on April 2 seemed to be building on positive indicators that surfaced during the Trump-Bin Salman meeting in the White House earlier in March. Accordingly, Trump is counting more on the Saudi flexibility in persuading Abu Dhabi to reconsider its calculations, not only toward overcoming the Crisis and holding the US-Gulf summit, but also Trump’s need to unite the Gulf ranks and securing their support of his escalation strategy vis-à-vis Tehran after exiting the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) on May 8.

Third, the position of Abu Dhabi appears to have exhausted of its diplomatic momentum in stimulating favorable decisions of Trump. Emirati Crown Prince Mohammed bin Zayed maintained his deep-seated belief he has made long-term political investment in Washington and his transactional conformity with business-minded Donald Trump would secure him a position of ‘power’ in the game. Andreas Krieg explains how “all levers of UAE state power were employed to broad-brush any revolutionary call for socio-political inclusion and pluralism as ‘terrorism’. Tens of millions of dollars were invested by the UAE, into the counterrevolutionary effort, to discredit any form of socio-political dissidence at home and abroad, Islamist or secular, as a strategic threat to regional stability – a narrative that was disseminated aggressively via PR firms to conservative think tanks and politicians in Europe, America, and Israel. The most prominent recipient has been Donald Trump whose realist foreign policy agenda in the region abandons Obama’s human rights conditionality in favor of returning to authoritarian stability.” (41) In short, It is very difficult for him psychologically to move away from his ‘victorious’ mindset or to re-examine, through the lens of rational and pragmatic thinking, the new modalities of the Gulf Crisis and Trump’s diplomatic maneuvering to settle it.

3. Adjustment of Perception

The US-Qatari Strategic Dialogue held in Washington focused on the main pillar of the US-Qatari relations despite the repercussions of the Crisis. Among the attendees were ministers of foreign affairs and defense in both countries, and at the end of the discussions of the meeting, a joint statement laid out several areas of mutual understanding and cooperation. (42) In terms of the Crisis, the significance of this strategic dialogue can be summarized in five main points:

|

1 |

Qatar and the United States discussed the Gulf crisis and expressed the need for an immediate resolution which respects Qatar’s sovereignty. |

|

2 |

The two governments expressed concern about the harmful security, economic and human impacts of the crisis. |

|

3 |

Qatar emphasized its appreciation for the role played by the United States in the mediation of the dispute in support of the efforts of the Emir of Kuwait. |

|

4 |

Qatar and the United States affirmed their backing for a strong Gulf Cooperation Council that is focused on countering regional threats and ensuring a peaceful and prosperous future for all its peoples. |

|

5 |

The two governments outlined a way forward together for the development of their partnership. |

Summary of the Strategic Dialogue Communique regarding the Gulf Crisis

[Complied by the author]

This shared vision of bilateral relations between Washington and Doha on the trajectory of the Crisis reflects a pragmatic outlook the White House and the political establishment hope will serve as a locomotive to restore the livelihood of the GCC. Despite the absence of Tillerson from the political scene, the approach of his predecessor Pompeo and his commitment to full implementation of Trump’s strategy solidify the emerging indicators of gradual détente by moving away from the stalemate and the escalation-for-escalation realist logic. Considering its political, strategic and psychological complexities, the Crisis would not be, in the final analysis, an exception to all crises and conflicts: hyper escalation, serious mediation, softening the rhetoric of animosity, and gradual disappearance of acts of vengeance while seeking an outcome that would save face for all parties.

The road to September is most likely to follow this trend in the transformation of the Crisis, unless the snowball of the US-Iranian standoff swallows the Crisis. The postponement of the US-Gulf summit for four months may imply some awareness, at the White house, of the requirements of mediation; and allowing adequate time for the psychological context and political mindsets of the parties to update their interpretations. Trump dispatched Pompeo to Riyadh on his first official mission after assuming his new position ushers to the White House's intention to close the Qatari dossier. Trump, who is not known for his multi-tasking capabilities, needs to focus on Iran and his pursuit of denuclearizing of the Korean Peninsula. In Washington's assessment, any rapprochement between the Gulf capitals remains a natural step toward shaping a nucleus of reconciliation. Such project of reconciliation will remain modest and gradual between what the seeds that were planted in April and what could be harvested in September.

(1) Whyte, W. H., Jr. "Groupthink", Fortune, March 1952, pp. 114–117

(2) Julian Borger, “US officials scramble to limit Donald Trump's diplomatic damage over Qatar tweets”, The Guardian, June 7, 2017 https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2017/jun/06/donald-trump-qatar-tweets-us-diplomatic-damage

(3) Patrick Wintour, “Donald Trump tweets support for blockade imposed on Qatar”, The Guardian, June 6, 2017 https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/jun/06/qatar-panic-buying-as-shoppers-stockpile-food-due-to-saudi-blockade

(4) Uri Friedman and Emma Green, “Trump's Speech on Islam, Annotated”, The Atlantic, May 21, 2017 https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2017/05/trump-saudi-speech-islam/527535/Bottom of F

(5) Julian Borger, “US officials scramble to limit Donald Trump's diplomatic damage over Qatar tweets”, The Guardian, June 7, 2017 https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2017/jun/06/donald-trump-qatar-tweets-us-diplomatic-damage

(6) Jacob Pramuk, “Trump muddles Rex Tillerson's message after he urges Gulf states to ease Qatar blockade”, CNBC, June 9, 2017 https://www.cnbc.com/2017/06/09/watch-secretary-of-state-tillerson-to-deliver-statement-to-the-media.html

(7) Andreas Krieg, “The Gulf Rift – A War over Two Irreconcilable Narratives”, Defense in Depth, June 27, 2017 https://defenceindepth.co/2017/06/26/the-gulf-rift-a-war-over-two-irreconcilable-narratives/

(8) Antony J. Blinken, ”President Trump’s Arab Alliance Is a Mirage”, The New York Times, JUNE 19, 2017 https://www.nytimes.com/2017/06/19/opinion/trump-isis-qatar-saudi-arabia.html

(9) Mohammed Cherkaoui, “The 'Trump Factor' and the Implosion of the Gulf Union”, Aljazeera Opinions, June 10, 2017 https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/2017/06/trump-factor-implosion-gulf-union-170610064645861.html

(10) Ishaan Tharoor, “The blockade of Qatar is failing”, The Washington Post, July 18, 2017 https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2017/07/18/the-blockade-of-qatar-is-failing/?utm_term=.214072c4d10e

(11) Sara Cobb, Speaking of Violence: The Politics and Poetics of Narrative in Conflict Resolution, Oxford University Press, 2013, p. 131

(12) Ahmed Al Omran, “Gulf media unleashes war of words with Qatar”, Financial Times, August 4, 2017 https://www.ft.com/content/36f8ceca-76d2-11e7-90c0-90a9d1bc9691

(13) Sarah Earthy and Ann Cronin, “Narrative Analysis”, in Researching Social Life, N. Gilbert (ed) (2008) 3rd Edition, London: Sage, http://epubs.surrey.ac.uk/805876/9/narrative analysis.pdf

(14) George C. Rosenwald and Richard L. Ochberg, “Storied Lives: The Cultural Politics of Self-Understanding”, Yale University Press; First Edition, 1992

(15) George C. Rosenwald and Richard L. Ochberg, “Storied Lives: The Cultural Politics of Self-Understanding”, Yale University Press; First Edition, 1992

(16) Kenneth Plummer, Telling Sexual Stories: Power, Change, and Social Worlds, Psychology Press, 1995

(17) Sarah Earthy and Ann Cronin, “Narrative Analysis”, in Researching Social Life, N. Gilbert (ed) (2008) 3rd Edition, London: Sage, http://epubs.surrey.ac.uk/805876/9/narrative analysis.pdf

(18) Ishaan Tharoor, “The crisis over Qatar highlights Trump’s foreign policy confusion”, The Washington Post, June 15, 2017 https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2017/06/15/the-crisis-over-qatar-highlights-trumps-foreign-policy-confusion/?utm_term=.29733fbf593f

(19) Irving Janis, "Groupthink", Psychology Today. November 1971. 5 (6): 43–46, 74–76.

(20) Whyte, W. H., Jr. "Groupthink", Fortune, March 1952, pp. 114–117

(21) Ashley Killough and Jeremy Herb, “Key senators pass on reacting to Trump Qatar tweets”, CNN, June 6, 2017 https://www.cnn.com/2017/06/06/politics/congressional-reaction-qatar-trump-tweets/index.html

(22) News Agencies, “US: List of Demands to Qatar should be Reasonable”, Aljazeera, June 21, 2017 https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2017/06/list-demands-qatar-reasonable-170621182213569.html

(23) Aljazera and News Agencies, “Arab states issue 13 demands to end Qatar-Gulf crisis”, Aljazeera, July 13, 2017 https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2017/06/arab-states-issue-list-demands-qatar-crisis-170623022133024.html

(24) Taimur Khan, “Arab countries' six principles for Qatar 'a measure to restart the negotiation process”, the National, July 19, 2017 https://www.thenational.ae/world/gcc/arab-countries-six-principles-for-qatar-a-measure-to-restart-the-negotiation-process-1.610314

(25) Taimur Khan, “Arab countries' six principles for Qatar 'a measure to restart the negotiation process”, the National, July 19, 2017 https://www.thenational.ae/world/gcc/arab-countries-six-principles-for-qatar-a-measure-to-restart-the-negotiation-process-1.610314

(26) aimur Khan, “Arab countries' six principles for Qatar 'a measure to restart the negotiation process”, the National, July 19, 2017 https://www.thenational.ae/world/gcc/arab-countries-six-principles-for-qatar-a-measure-to-restart-the-negotiation-process-1.610314

(27) Habib Toumi, “Crisis resolution is up to Qatar, Al Jubeir says”, Gulf News, May 24, 2018 https://gulfnews.com/news/gulf/qatar/crisis-resolution-is-up-to-qatar-al-jubeir-says-1.2174195

(28) The National, “Saudi Arabia says Qatar continues to propagate hatred amid US efforts to resolve crisis”, February 4, 2018 https://www.thenational.ae/world/gcc/saudi-arabia-says-qatar-continues-to-propagate-hatred-amid-us-efforts-to-resolve-crisis-1.707513

(29) James Dorsey, “Gulf Media Wars Produce Losers, Not Winners”, Fair Observer, August 9, 2017 https://www.fairobserver.com/region/middle_east_north_africa/gulf-crisis-news-qatar-uae-saudi-arabia-arab-world-news-headlines-98712/

(30) Aljazeera News, “Qatar's Blockade in 2017, Day by Day Developments”, February 18, 2018, Aljazeera, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2017/10/qatar-crisis-developments-october-21-171022153053754.html

(31) Gardiner Harris, “State Dept. Lashes Out at Gulf Countries Over Qatar Embargo”, The New York Times, June 20, 2017 https://www.nytimes.com/2017/06/20/world/middleeast/qatar-saudi-arabia-trump-tillerson.html

(32) Rami Khouri, “Trends in Qatar Stand-Off”, The Cairo Review of Global Affairs, August 5, 2017 https://www.thecairoreview.com/tahrir-forum/trends-in-qatar-stand-off/

(33) Gardiner Harris, “Pompeo’s Message to Saudis? Enough Is Enough: Stop Qatar Blockade“, the New York Times, April 28, 2018 https://www.nytimes.com/2018/04/28/world/middleeast/mike-pompeo-saudi-arabia-qatar-blockade.html

(34) Brookings, “The geopolitical and security implications of the Gulf crisis” Conference, October 30, 2017 https://www.brookings.edu/events/the-gulf-crisis-what-next-for-the-region/

(35) The White House, “Trump-Emir of Kuwait News Conference”, September 7, 2017 https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2017/09/07/remarks-president-trump-and-emir-sabah-al-ahmed-al-jaber-al-sabah-kuwait

(36) Calamur, Krishnadev. “America Wins the Gulf Crisis”, The Atlantic, January 31, 2018 https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2018/01/qatar-us/551873/

(37) Department of State, “Deputy Secretary John J. Sullivan’s Meeting With Saudi Foreign Minister al-Jubeir”, Office of the Spokesperson, May 21, 2018 https://translations.state.gov/2018/05/21/deputy-secretary-john-j-sullivans-meeting-with-saudi-foreign-minister-al-jubeir/

(38) Aljazeera, “Trump: US-Qatar ties 'work extremely well'”, April 11, 2018 https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2018/04/trump-qatar-ties-work-extremely-180410135820276.html

(39) Rami Khouri, “Trends in Qatar Stand-Off”, The Cairo Review of Global Affairs, August 5, 2017 https://www.thecairoreview.com/tahrir-forum/trends-in-qatar-stand-off/

(40) Rami Khouri, “Trends in Qatar Stand-Off”, The Cairo Review of Global Affairs, August 5, 2017 https://www.thecairoreview.com/tahrir-forum/trends-in-qatar-stand-off/

(41) Andreas Krieg, “The Gulf Rift – A War over Two Irreconcilable Narratives”, Defense in Depth, June 27, 2017 https://defenceindepth.co/2017/06/26/the-gulf-rift-a-war-over-two-irreconcilable-narratives/

(42) Office of the Spokesperson, “Joint Statement of the Inaugural United States-Qatar Strategic Dialogue”, State Department, Washington, DC, January 30, 2018 https://www.state.gov/r/pa/prs/ps/2018/01/277776.htm