|

|

[AlJazeera]

|

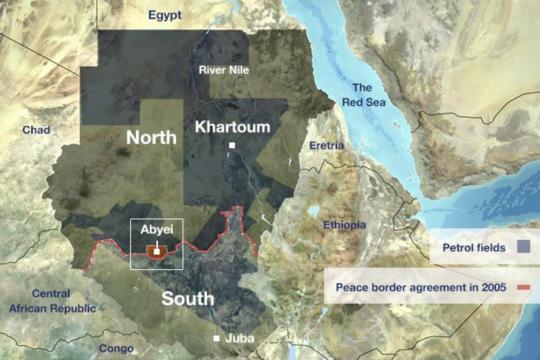

| Abstract The struggle for the border area of Abyei between the two Sudans is multi-faceted. The Khartoum-Juba dispute is over the question of which state the area belongs to, and the dispute between the Ngok Dinka and Misseriya tribes is over ownership rights in Abyei. This struggle is part of the wider conflict between North and South Sudan, which ended with the separation of the South in 2011. Despite a lapse of two years since the separation, the fate of the Abyei region remains undecided, with no solution on the horizon. Both Sudan and South Sudan are absorbed in their internal challenges, and accordingly lack the ability or consensus to solve the dispute. |

At the end of October 2013, the Ngok Dinka tribe in Abyei carried out a unilateral referendum to decide which state their area should join. Stakeholders rejected the move; concerned that it would undermine the fragile arrangements that had been made to peacefully settle the dispute. This could consequently trigger new confrontations that would involve the two Sudans, and, in fact, the entire region.

Oil-rich Abyei is one of the outstanding issues between the states of Sudan and South Sudan, with each insisting that the area belongs to them. Sudan considers it part of South Kordofan, while South Sudan maintains it is part of Northern Bahr el Ghazal. In 2009, the international Permanent Court of Arbitration redrew the borders of the region, which both parties accepted.

Within the scenario of this state-state conflict, there is another dispute between forces claiming ownership over the area. The Ngok Dinka tribe claims ownership, and refuses to recognise the right of the Misseriya tribe to Abyei. The latter tribe wants to join Sudan, and insists that it is native to the area. It claims that it needs to find grazing areas for its herds due to its seasonal migration to the North. .

The Ngok Dinka plebiscite triggered sharp tensions among the various parties concerned with the fate of the region.

Referendum without a reference

The result of the referendum, which was conducted unilaterally by the Ngok Dinka on 27 October 2013, was 99.99 per cent in favour of annexing the disputed Abyei between Sudan and South Sudan to the latter. According to the electoral committee, 65 000 people took part in the plebiscite. The results were announced on 31 October, but were rejected by all stakeholders, including the African Union (AU), the South Sudan government, the Sudanese government, and the Misseriya tribe, whose members are co-inhabitants of the disputed area with the Ngok Dinka. The Misseriya maintain that the referendum was illegal, and that it should have been regulated under an agreed joint commission as stipulated by the relevant documents, specifically the resolutions of the African Peace and Security Council and the UN Security Council, as well as the Abyei Protocol of 2009. It also refers to the Abyei Referendum Law passed by the Sudanese parliament on 30 December 30 2009, when the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement (SPLM) was a partner in government, and before the separation of the South. These documents stipulate that a plebiscite should be organised by a commission agreed on by the two parties to the dispute and in line with set measures. Local, regional and international parties should monitor such a plebiscite, and after stability is restored to the area, civil institutions listed in the Abyei Protocol should serve as a guarantor of the plebiscite. These include a joint administration, a legislature, and a joint police force. Since none of these requirements were met by the unilateral referendum conducted by the Ngok Dinka, the stakeholders rejected it.

During his visit to Juba days ahead of the referendum, the Sudanese president, Omar al-Bashir, made an agreement with South Sudan’s president, Salva Kiir, in a move to derail the plebiscite, as the two leaders prioritised the formation of civil institutions elaborated on in the relevant documents. They also agreed to allocate two per cent of the value of oil produced in the area, or that passes through it, to development efforts. This was deemed necessary to achieve stability in preparation for improved conditions for a future referendum. Each effort, however, faces the critical issue that has hindered a settlement; that of voter eligibility and defining who is entitled to participate in the poll. The Abyei Protocol, supported by the International Court of Justice in The Hague in 2009, limits the right to vote to the nine clans comprising the Ngok Dinka and the Sudanese dwelling in the area. The Misseriya and their supporters, like the Sudanese government, claim that they, among others, are indigenous residents of the area. In contrast, the Dinka and the South Sudan government argue that the Misseriya are simply nomads who have herding but no residency rights.

Ngok Dinka: referendum calculation

Why did the Ngok Dinka take this unilateral step?

1. In September 2012, the chairperson of the African Union High-Level Implementation Panel for Sudan and South Sudan; Thabo Mbeki, suggested a plebiscite for October 2013. The African Peace and Security Council rejected the suggestion. In October, Ngok Dinka also took advantage of the summer journey of the Misseriya outside the area.

2. The result of the referendum tilts the scale in favour of tribal forces that want to join South Sudan, and alienates those who opt for a middle ground. It accordingly appears that the hard-line forces aimed to strengthen their position at the expense of those who sought conciliatory solutions.

3. The Ngok Dinka hoped that their step would trigger support from the southern forces. This could encourage political forces to recognise the plebiscite as legitimate and to pressure South Sudan’s government. The Ngok Dinka could also use the achievement to bolster their popularity in future elections. Indeed, southern parties forwarded a memorandum to Kiir demanding that he recognise the outcome of the Abyei referendum.

4. Several observers note that the referendum illustrated a lack of hope for an agreed solution, and reflected the state of impasse that has long characterised the issue. Furthermore, it mirrored the power struggle in the South, where Kiir deposed a group of SPLM leaders, including some from the Ngok Dinka. Foremost among this group was the Abyei Referendum High Committee Chair, Deng Alor, who had been dismissed from his ministerial post by Kiir and subjected to investigation as a prelude to a trial. As Abyei does not currently fall under the jurisdiction of the South, Ngok Dinka needs geopolitical justification to secure its participation in the central administration in Juba. This needs to occur without the perception of this tribe as ‘outsiders’ by southerners.

5. Observers also believe that the unilateral plebiscite was conducted to involve the international organisations that have long been key supporters of the South in the international arena. The outcome of the poll is likely to renew these organizations’ campaigns in support of Ngok Dinka, and mobilise international powers to pressure Sudan to accept a solution compatible with Ngok Dinka’s goals.

6. Certain Misseriya leaders believe that the move was intended to provoke a violent reaction from them. This would in turn attract the sympathy of global public opinion, thus discarding all relevant documents, agreements and protocols, and create a new reality that would see the Misseriya tribe lose its rights.

Misseriya: rejection with caution

The referendum caused confusion and complications at all levels and among all parties. The Misseriya described it as desperate and reckless, and argued:

1. The step was illegal and in violation of all the covenants, agreements, protocols and laws previously agreed on as terms of reference regarding Abyei.

2. A group of Misseriya called for a similar plebiscite in which all residents of Abyei could participate, including Ngok Dinka members who lived in other parts of Sudan and who had rejected the referendum. They said that the suggested referendum could be monitored by international and regional organisations. Some, however, believe that any unilateral plebiscite is illegal and would violate the relevant laws and agreements. Nafe Ali Nafe, an assistant to President Bashir, was among those who proposed a counter referendum and said the government would conduct it. He claimed that the poll would provide evidence that Ngok Dinka constitutes a minority in comparison to all the Abyei residents from North Sudan, and not only the Misseriya. He maintained that the plebiscite would prove that Abyei was truly a northern area.

3. The Misseriya are suspicious of the African Peace and Security Council’s stand on the referendum. The council rejected and denounced the poll publicly, and called on the UN Security Council to denounce it. Nevertheless, the Misseriya maintain that the AU failed to stop the referendum even though it has more than 4 000 troops deployed in the area on a peacekeeping mission. They also cast doubt on the position of the South Sudan government, accusing it of collaborating with the Ngok Dinka. Although the government rejected the plebiscite, they said it gave state employees belonging to the Ngok Dinka leave to register and vote in the referendum. Most importantly, the Misseriya question the identity of the funders of the referendum. Despite the fact that all parties rejected the referendum, some sources estimated that it had cost $5 million. These suspicions were deepened when South Sudanese information minister, Michael Makuei, called on the Ngok Dinka to present the results of the referendum to the AU.

4. The Misseriya leadership threatened that if South Sudan or the African Peace and Security Council recognised the outcome of the plebiscite, it would overrun Abyei and gather on the 1 January 1956 line, the recognised border between Sudan and South Sudan. They said that they had already mobilised a huge army of fighters, and would shut down the oil pipelines and border crossings between the north and the south in their area. They claimed that a large number of tribes would rush to support them.

5. Misseriya believe that direct talks between the leaders of the two tribes, without the involvement of governments and ruling parties form either country without regional and international organisations, can result in a win-win solution.

Echoes of the referendum in Khartoum

The referendum caused confusion and tension among all parties. Khartoum is preoccupied with the volatile political situation and economic development in the north. It therefore simply highlighted the recently concluded agreement between Bashir and Kiir to establish civic institutions and move forward in creating the required climate of stability. This would be based on the administrative and security arrangements agreement in paragraphs 41 and 42. The two presidents would assume political and security responsibilities, and there would be no role for the tribes involved in the dispute.

Khartoum reasserted its confidence in the positions of the South Sudan government and the African Union by rejecting the referendum. Sudanese observers said that the most important development accompanying the results of the referendum was the agreement by the Sudanese government to an AU proposal to include the UN Security Council in efforts to conduct a referendum to solve the conflict. In light of America's conflictual relationship with Sudan, which was partly to blame for Sudan’s thorny history with the Security Council, this agreement would complicate matters, especially for the Sudanese government.

Prospects and caveats

Abyei is a very complex issue that evolves amid fragile stability that could break down at any minute into military confrontation. Given the current information, several scenarios are possible:

1. The clash: The government of South Sudan might, under pressure, announce its recognition of the outcome of the referendum. Alternatively, the SPLM might raise a flag in an Abyei town. This would anger the Misseriya, who might carry out their threat to invade Abyei to the 1956 borders. Consequently, the relationship between the two Sudanese states would collapse. The Misseriya invasion of Abyei may be coupled with the closure of the border between north and south, and the disruption of the flow of oil that passes through their lands. This would undermine the strenuous cooperation agreements reached between the two countries, upon which both rely in order to save their deteriorating economies.

The security situation resulting from the invasion might drag the two countries into armed confrontation under the pressure of public opinions in both. The security situation in the region may consequently deteriorate and spill over beyond the borders of the two countries.

Extremely difficult economic conditions might emerge, with repercussions that will be too difficult for the two countries to handle. This may push them into a state of disintegration on the security, political and economic fronts, and Somalisation.

2. Conciliatory scenario: The two governments may be able to form legislative and executive civil institutions, along with a police force. They may manage to achieve a degree of development and stability and defuse acute tension. In so doing, they will create a climate for calm dialogue between the parties, leading to:

• A referendum process after agreement on the approach to manage and oversee it, and to accept the results that the vote might produce;

• Direct negotiations between the Misseriya and the Ngok Dinka on the backdrop of positive coexistence and joint management of civil institutions. This may open up other opportunities for coexistence.

3. Division scenario: The African Union had proposed dividing the region into two geographic entities – one for the Misseriya and the other for the Ngok Dinka. This might become a popular option despite its vagueness. Such a scenario may be taken up if there are not many peaceful alternatives.

4. Some Sudanese writers, including Professor Mirghani Hamour of the University of Khartoum, suggested that the Abyei area becomes an integration zone affiliated with the presidency in both countries. A joint regional presidential council comprised of representatives from both countries would rule it. In this case, he says, Abyei should evolve into an integration entity with an independent legal personality, and citizens on both sides of the border could enjoy dual citizenship. This scenario may be taken up.

5. Continuation of the attrition scenario: Abyei may remain a chronic headache for both states for some time to come, similar to other ongoing international problems, including Kashmir between India and Pakistan, the Western Sahara between Morocco and Algeria, and the Cyprus issue between Greece and Turkey. In this case, the relations between the two Sudans will remain primarily conflictual.