|

| [Syria] |

| Abstract The recent successive setbacks suffered by Assad regime forces are causing as much alarm among Bashar al-Assad’s opponents as they are among his allies. This has also prompted the political opposition to try to use the new shift in the balance of power to push for a political process that would lead to a transitional phase, ending more than four years of deadly conflict that can be easily called a brutal civil war. The Syrian armed opposition, despite appearing more and more like a tiny detail in a much larger game of regional and international interests, can still force changes to regional and global agendas, just as much as it can still force the regime and its allies to change tactics on the ground. All that alone, however, is nowhere near enough. Unless translated into real, tangible political results that would maintain Syria’s unity, and help rebuild the country, the opposition’s victories on the ground will remain but mere, isolated events of little significance. |

Introduction

Since early this year, Syria has been experiencing some significant changes on the ground. Jaish al-Fath, or the Army of Conquest – a coalition of several opposition groups, including Ahrar ash-Sham, Faylaq al-Sham (Sham Legion), and al-Nusra Front – captured Idlib, the capital of its namesake governorate and the second major city to be freed from the regime’s control after al-Raqqah, which had been liberated by the rebels in March 2013 before it fell to the Islamic State, which made it their capital. In late April, the opposition seized Jisr al-Shughour, the governorate’s second largest city and its most important one given its strategic location on the roads that connect the area to the Syrian coast to the west and al-Ghab Plain in the Hama countryside to the south.

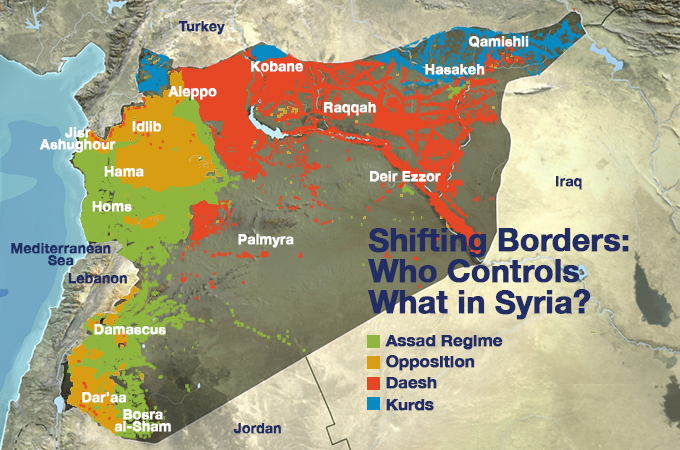

In the south, around the same time, the opposition took control of Bosra al-Sham, Hezbollah’s stronghold in the Horan plain. They also took the Nasib border crossing, the regime’s last land link with Jordan. The 52nd Brigade, the regime’s biggest military unit in Dar’aa, was also captured recently by the opposition. Battles are ongoing in the vicinity of al-Thala air base just west of al-Suwaida, as well as in various areas around Aleppo. In the meantime, the Islamic State (IS or Daesh) managed to capture Palmyra in the middle of the Syrian Desert, threatening Homs and Hama from the east, and shrinking the regime’s land control to a mere third of the Syrian Arab Republic’s geographic area, with half of the country’s population still under regime control.

This paper addresses ramifications of the armed opposition’s recent gains on the ground and attempts to explain their causes, regional and international reactions to them, and their impact on the warring parties in Syria (both the regime and the opposition). The paper concludes with an attempt to foresee possible scenarios of how the Syrian issue might unfold, with a special focus on whether or not the recent developments would reinvigorate the political process that has been frozen since early 2014.

Winds of change: the regime retreats

The latest developments on the ground came in the wake of a series of setbacks experienced by the Syrian armed opposition over the past two years. This started when the city of al-Qusayr (in the Homs countryside) fell to the regime’s forces and Hezbollah militias in May 2003, followed by the opposition’s ouster from Homs’ Old City. Hoping to achieve the same in Aleppo, the regime then tightened its siege on the neighbourhoods controlled by opposition factions.

Politically, the chemical disarmament agreement, and the ensuing UN Security Council Resolution 2118 that regulated the handover and disposal of the regime’s chemical weapons, broke through the regime’s political isolation since the crisis began. This emboldened the regime to hold unilateral presidential “elections” in June 2014, which incumbent Bashar al-Assad won by a landslide with eighty-eight per cent of the vote. As Daesh commenced their rise after storming into Mosul, and after having claimed as their own the deadly attack on French satirical weekly Charlie Hebdo in January, whispers about the possibility of rehabilitating the regime began to rise to a buzz in Western circles, to the point that US Secretary of State John Kerry publicly stated the international community would “have to negotiate” with Assad.(1)

It was amid all this that the opposition’s streak of bad luck turned, enabling them to force change both on the ground and politically. Taking advantage of the rekindled Saudi–Turkish relations after King Salman’s ascension to the throne, and emboldened by the new political winds that blew through the region after Saudi Arabia’s intervention in Yemen, the opposition’s forces were able to tip the balance somewhat in their favour throughout the country. These achievements were helped by joint operations centres that have boosted field coordination among opposition factions, but as of yet have stopped short of uniting them outright.

The successive setbacks suffered by regime forces raised concerns among Assad’s opponents and allies alike. The political opposition attempted to use the new situation to redouble efforts towards a reboot of the political process, which might eventually lead to a transitional phase that would end more than four years of a conflict that has destroyed the country.

The regime, on the other hand, took a two-pronged approach: obtaining more military and financial support from Iran, and asking Russia to sponsor and handle previously shut political channels, in an apparent attempt to outmanoeuvre any international moves to circumvent or sideline the regime. This possibility was made clear after the June 2015 meeting of the Anti-Islamic State Coalition in Paris issued a declaration underlining the lack of urgency on the part of Assad’s regime to fight Daesh and calling for the launch of a comprehensive, sincere political process that would implement the principles of the Geneva Declaration.(2)

The international level: a convergence of fears

The gains achieved by the opposition on the ground jump-started Russo–American communication which had been severed since the failure of the Geneva II Conference in February 2014. At the time, Washington accused Russia of reneging on a deal reached between Russian Minister of Foreign Affairs Sergey Lavrov and US Secretary of State John Kerry about a month earlier, in which both parties agreed to pressure their respective allies to get the regime and the opposition to agree to a transitional governing body. However, the subsequent Ukrainian crisis and Russia’s annexation of the Crimean Peninsula killed every chance of Russo–American communication, at least until more recent developments revived them.

The reinvigorated Russo–American action on Syria came as an attempt to control the severe damages suffered by the regime at the hands of the opposition, which was further emboldened by a new political atmosphere brought about by Operation Decisive Storm. As America’s allies grew more and more disgruntled by its policies in the region, they took measures independently of the US, with a clear Saudi drive to curb Iranian influence in Yemen.

Hence, as the regime retreated further under the opposition’s intense pressure, and as Daesh captured Palmyra, Kerry made a long-overdue visit to Moscow to meet Russian President Vladimir Putin on 11 May 2015. The visit took place two days prior to the US–GCC Camp David summit and only days after Kerry met with his GCC counterparts in Paris, where Syria was the primary discussion topic. The US and Russia agreed that the current situation becoming the status quo in Syria would lead to the very results both sides had always claimed they were trying to avoid: the collapse and implosion of Syrian state institutions, starting with the armed and security forces, and its takeover by jihadi groups, Daesh in particular.(3)

The advances made by the opposition pushed the Russians to put an end to their strategy of supporting the regime all the way to victory: they finally conceded that there could be no military resolution to the conflict in Syria and called for following the principles set in the Geneva Declaration in June 2012 as a necessary step to prevent Syria from collapsing into the hands of jihadi groups.(4)

In terms of Washington, its prior strategy of “letting the fire put itself out” in terms of the Syrian revolution has failed thus far, and even its “air strike approach” to Daesh has not had a significant impact on outcomes – Daesh continues to expand. As it stands now, Washington is running the risk of losing complete control in Syria, especially now that its regional allies, having grown increasingly dissatisfied with its policies in the region, have begun adopting more independent policies of their own. At the Camp David summit in May, which brought US President Barack Obama together with GCC leaders, the rift appeared to be so intense that the leaders of four of the six GCC states, the most prominent of which was King Salman of Saudi Arabia, did not attend the summit. This was despite an invitation by President Obama to discuss US foreign policies in the Middle East and the Gulf. Despite reports of the absence of a unified GCC position at the summit, all six states expressed the same concern: the Obama administration’s lax handling of Iran’s growing influence, which continues to threaten to hurl the entire region into all-out conflict and extremism.(5)

As the Saudis pursued more aggressive policies to defend their interests with little concern for the US, including their efforts to change things on the ground in Syria before the Camp David summit, Syrian opposition factions also started to operate more independently from the control centres that provided them with funding and armament – the decisions of which were controlled by the US. The Syrian opposition’s independent shift can be credited to the capture of vital sources of funds, not least of which include border crossings and production facilities of oil, gas, wheat, phosphate and more. Additionally, the opposition has developed the skills to manufacture a not insignificant number of small and medium weapons. They won large weapon and ammunition caches from retreating regime forces, gaining even more independence from American-controlled foreign aid. All of this has been clear in the most recent clashes.

For these reasons, Washington moved quickly to contain the situation. A mere week after Kerry’s visit, Daniel Rubinstein, US envoy to Syria, arrived in Moscow to brief Russian officials on a US vision for a political resolution of the Syrian crisis that would keep Assad in place in its early stages. This came amid expectations that UN Special Envoy Kofi Annan’s team would return to Syria to oversee the implementation of the Geneva Declaration in accordance with an agreed-upon Russo–American interpretation that still requires regional players to be on board.(6)

Growing Iran and Saudi roles

Given that much of the opposition’s recent triumphs on the ground were seen as the embodiment of a Saudi-Turkish-Qatari accord, they caused alarm in Iran. This was so much so that Syrian defence minister Fahd Jassem al-Freij reportedly made a visit to Iran after Idlib and Jisr al-Shughur fell in early May and asked for the activation of the joint defence agreement of 2006, which includes a clause that states that any aggression against Syria is an aggression against Iran, meaning that Iran can send troops to Syria if requested.(7)

The Iranians spared no time in fulfilling the Assad regime’s request. A few thousand Revolutionary Guard and pro-Iranian foreign militia troops were sent to Syria to help defend the regime’s strongholds in Syria’s capital, Damascus, and on the Syrian coast, and to try to turn things in the regime’s favour in the south. For this, Iran played the “conflict-with-Israel and the concept of resistance” card, an important image-builder for Iran and its regional influence.

But Iran, which moved quickly to prevent a domino effect on its supporters in Syria, soon realised that the recent series of setbacks had already made it extremely unlikely that a victory would enable the regime to regain the same control of the country it had prior to March 2011.

Thus, the Iranians began to think of ways to protect their Syrian assets from any contingencies. In exchange for agreeing to support Assad against the opposition, Iran asked for sovereign collateral on Syrian soil, in the form of real estate, property, seaports, airports and various natural resources, as a guarantee for the repayment of funds they had granted to the Syrian regime throughout the crisis in the form of low-interest loans and credit lines.(8) The Iranians asked for this only after they saw that the regime’s grip on the productive part of Syria (oil and gas fields, and wheat farms in the country’s east, north-east and desert) had receded, maintaining control only on the consumable part (in the country’s west). This meant a heavier economic and financial burden for Iran, which has yet to reach a permanent, verifiable settlement over its nuclear programme in order to lift sanctions.(9)

Circling the wagons

Seeing how recent developments on the ground have put the regime in a bind, its allies are having increasing doubts about its ability to hold its ground. Additionally, its support base is gradually coming undone at the seams as a result of the great losses it suffered after the Tabaqa airport fell to Daesh in September 2014. This highlights just how far the regime is from being able to bring about a full military victory.

Beyond asking Iran for help in containing the aftermath of the most recent setbacks, the regime also turned to its Russian allies not only to secure military support, which Syrian interior minister Mohammad al-Shaar had asked for when he visited Moscow in May, but also, according to Russian Deputy Foreign Minister Mikhail Bogdanov, to ask the Russians for help setting up a third “Moscow Forum” to consult with representatives of the opposition.(10) Through this request, the regime wanted to probe just how much the Russians were in sync with the Americans on a resolution to the Syrian crisis. In addition, the regime was probably trying to set forward some ideas for a limited set of concessions that the opposition – which is more concerned about the growing power and influence of armed opposition factions than the longevity of the regime – would possibly agree to. The regime’s move was meant to portray itself to the international community as the protector of minorities and – given its long experience – the player most capable of dealing with jihadists.

For their part, the political opposition were quick to take advantage of the regime’s setbacks. They held conferences and meetings in hopes of reconciling their differences and patching up rifts, and to reassert their role in shaping Syria’s future. The coalition boycotted consultations in Geneva held by envoy to Syria Staffan de Mistura on the premise that he was colluding to send the opposition into disarray, prompting the armed factions to boycott as well. Instead, the coalition and the armed factions held a meeting among themselves in Gaziantep on 25 April 2015. This meeting, for the first time ever, brought the leaders of the more prominent armed factions together with leaders of the National Coalition. They agreed on broad principles for any possible future political solutions, chief of which was the absolute rejection of the Assad regime remaining in power.

However, many complications still stand in the way of an agreement that will be a true “political representative” of the Syrian opposition as well as the participating military factions. In talks recently held in Amman, Jordan, delegates from the National Coalition and Southern Front failed to agree upon a way to incorporate the warring factions into the coalition, within the framework of an expansion and restructuring process that would prepare the opposition for next steps. It is expected that the creation of a political body that would represent, among others, the military forces on the ground, would be one of the objectives of calls for an all-encompassing conference for the Syrian opposition in Riyadh this summer. Backed by Qatar and Turkey, Saudi Arabia aims to bring together all strains of the Syrian opposition to get them to agree on a singular vision for the conflict’s resolution and come up with specifics for a transitional stage and the future of the country, including the form of government, the status of minorities, and many other issues requiring clarity. This vision is necessary in order to create a convincing, viable alternative to both Assad’s regime and to Daesh, and to expedite the resolution of the crisis.

Future scenarios

Given the armed opposition’s recent achievements on the ground and the ensuing political activity, the Syrian issue is poised to follow one of three scenarios:

1. A workable solution: an international consensus (or, more specifically, a Russo–American one) would push for a widely accepted interpretation of the Geneva Declaration. Of course, such consensus would require cooperation from regional players, be they friends of the opposition (Saudi Arabia, Turkey and Qatar) or the regime’s allies (Iran), to pressure Syria’s warring parties to accept such a solution. Should all parties get on board, there would probably be a “Geneva III”, with the Iranians participating this time around, facilitated either by de Mistura or a successor. This scenario would be driven by pragmatism on the parts of each and every external party involved in the Syrian crisis, primarily out of fear that the country could slip into all-out chaos and become a regional hotbed of extremism and terrorism. The latest setback suffered by the regime might help push Iran, which itself is feeling the pain of being involved in so many conflicts throughout the region, to settle for a political solution that would preserve some of its interest in a unified Syria. But this could take place only after a possible deal over its nuclear program has secured international – or, more specifically, American – recognition for its legitimacy and brought it back into the regional fold.

Only in this case would there be a possibility for unified efforts that would push for a joint regime–opposition government, which would preserve what’s left of Syria’s institutions (including a restructured security apparatus and armed forces in particular, with moderate opposition factions incorporated into them). In addition, this would allow for redirecting resources towards fighting the Islamic State and possibly other transnational jihadist groups. This scenario has recently grown more likely, particularly after news leaked about possibly giving Assad asylum in Russia as part of an agreement with Moscow to fight Daesh. These discussions apparently occurred during G7 summit discussions in Germany on 8 June 2015.(11) This scenario is further bolstered by the invigorated communications between Russia and Saudi Arabia after Prince Mohammed bin Salman, the Saudi defence minister, held talks with Russian President Putin in Moscow to prepare for an anticipated visit by Saudi’s King Salman. All of this coincided with many reports of a Russo–American consensus on the Syrian crisis.(12)

There are two obstacles to this scenario, however: the Saudi–Iranian conflict and the affiliation of al-Nusra Front, a component of the Syrian armed opposition, with al-Qaeda. It would be hard for Saudi Arabia and Iran to reach a Syria-only agreement without resolving all their other differences, which are inextricably linked to the Syrian conflict, such as Hezbollah’s situation in Lebanon and the status of Sunni Arabs in Iraq. Also, al-Nusra Front cannot possibly break away from al-Qaeda without suffering a severe and possibly debilitating hit to its internal structure, which is largely made up of foreign elements.

2. Maintaining the status quo: this means that the conflict would continue at the same pace and prevent any possibility of a decisive military triumph for either side in the foreseeable future, along with a lack of regional and international willingness to push for a political solution, while external players continue to be involved in a proxy war on Syrian soil.

In this scenario, the balance of power on the ground would remain largely unchanged. While the opposition’s allies would increase their support to bring about a real breakthrough so as to pressure the regime to accept a political solution, the latter’s allies would also shore it up to thwart any attempts to induce a dramatic shift in the balance of power that would translate into political concessions. This would effectively splinter the country into pieces, each falling under the control of the regime, Daesh, the Kurds or other insurgent factions. The chances for such a scenario rest on unsustainable factors: maintaining the current balance of power, whether among Syrian warring parties or external players involved in the conflict, would be impossible because recent developments indicate that all of the parties’ resources are, after all, finite. Nowhere is this manifested more clearly than in the Syrian regime’s inability to make up for casualties among its troops. Its dependence on minorities gave it a narrow support base, and those minorities cannot continue to supply the regime with fresh recruits indefinitely.

Additionally, the continuation of the status quo would run the risk of new players getting involved in the conflict. Furthermore, these new players might even become major players, or, worse, they might turn out to be the conflict’s biggest benefactors. Nowhere is this more evident than in the example of the Islamic State, which has managed to expand into the areas that have slipped out of the regime’s control, with their threat now looming over Damascus, the capital city.

3. All-out chaos: the regime would continue to slowly, steadily unravel at the seams, taking the Syrian state’s institutions down with it, hollowed out by military exhaustion and financial attrition, which has been going on for more than four years now, all the way to its final implosion. The regime might even destroy itself from the inside out as successive blows dealt to it at the hands of the opposition continue to chip away at the morale of its people. This may be especially true if the opposition begins to target the regime’s strongholds in the Hama countryside or the coast, or if major cities like Aleppo, Deir Ezzor, Hasakeh, Dar’aa, Quneitra and Hama fall. These cities are all regional urban hubs, either completely or partially besieged by Daesh, which controls most of the Syrian desert, or the opposition, which is approaching Hama’s countryside from the north after capturing most of the Idlib province, and moving closer to Damascus from Dar’aa and Quneitra in the south.

If this scenario comes about, Syria would slip into complete and utter chaos. Daesh, which already controls or has influence in half of the country, would take over the rest of it – the one thing that all external parties agree cannot be allowed to happen. This scenario is highly unlikely, however. The only player that is trying to bring the situation to this is Daesh, but they cannot, because they are simply up against too many forces within Syria – the regime and the armed opposition – and abroad, namely, the international community.

Conclusion

Perhaps it goes without saying that scenario number one – a workable, agreed-upon solution – is the best alternative for all parties, without exception. It would maintain a unified Syria and prevent the country from slipping into chaos and extremism that would have serious implications and ramifications not only for the Syrian people, but also for the country’s neighbours and international security. But reaching such a solution would not have been possible without the recent developments on the ground. The latest streak of victories by the Syrian armed opposition raised concerns in Washington and Moscow that the Syrian regime might implode before a suitable alternative is ready to fill the ensuing power vacuum. This jump-started efforts to revitalise the political process that had been in deep freeze since the failure of the Geneva II convention in February 2014. These developments also brought the regime and its allies to the realisation that they cannot possibly turn the military situation in their favour anymore, which they have been trying to do ever since the Syrian revolution turned violent.

Taking all of this into account, it may be tempting to say that the Syrian armed opposition, which had recently been looking like little more than a tiny detail in a much larger game of regional and international interests, might still be able to force shifts in regional and international agendas, and cause the regime and its allies to change tactics. But that alone is not enough. Unless the opposition’s triumphs are translated into political results that would maintain the integrity of Syria’s national soil and rebuild the country, they will remain but mere, isolated events. It will take a mature political body, one capable of representing the warring factions and regulating relationships with and among them, in order for the armed opposition to come under its fold and be run by it. Absent such a body, it will not be possible to produce an alternative that is capable of keeping the country from slipping into chaos should the regime implode or at least be a credible negotiator should the parties involved choose to head towards a political solution.

___________________________________________

Copyright © 2015 Al Jazeera Center for Studies, All rights reserved

References

1. AlJazeera and Agencies, “Kerry Calls for Negotiating with Assad as National Coalition Insists He Must Go” [Arabic], AlJazeera, 15 March 2015, http://www.aljazeera.net/news/arabic/2015/3/15/%D9%83%D9%8A%D8%B1%D9%8A-%D9%8A%D8%AF%D8%B9%D9%88-%D9%84%D9%85%D9%81%D8%A7%D9%88%D8%B6%D8%A9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A3%D8%B3%D8%AF-%D9%88%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A7%D8%A6%D8%AA%D9%84%D8%A7%D9%81-%D9%8A%D8%B4%D8%AA%D8%B1%D8%B7-%D8%B1%D8%AD%D9%8A%D9%84%D9%87.

2. AlSouria and AFP, “International Coalition to Fight ISIS Calls for Expedient Political Process in Syria” [Arabic], Al-Souria, 2 June 2015, https://www.alsouria.net/content/دول-التحالف-الدولي-ضد-تنظيم-الدولة- تدعو-لإطلاق-عملية-سياسية-سريعاً-بسورية

3. Michelle Abu Najm, “Discord Over Assad’s Fate, Accord Over Unified Syria in De Mistura Consultations” [Arabic], Asharq al-Awsat, 11 June 2014, http://aawsat.com/home/article/381836/%D9%85%D8%B5%D8%A7%D8%AF%D8%B1-%D8%A7%D8%AE%D8%AA%D9%84%D8%A7%D9%81-%D8%AD%D9%88%D9%84-%D9%85%D8%B5%D9%8A%D8%B1-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A3%D8%B3%D8%AF-%D9%88%D8%A7%D8%AA%D9%81%D8%A7%D9%82-%D8%B9%D9%84%D9%89-%D9%88%D8%AD%D8%AF%D8%A9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AF%D9%88%D9%84%D8%A9-%D9%81%D9%8A-%D9%85%D8%B4%D8%A7%D9%88%D8%B1%D8%A7%D8%AA-%D8%AF%D9%8A-%D9%85%D9%8A%D8%B3%D8%AA%D9%88%D8%B1%D8%A7.

4. Asharq al-Awsat, “Moscow Changing Tack on Relationship with Assad”, Asharq al-Awsat, 31 May 2015, http://www.aawsat.net/2015/05/article55343744/moscow-changing-tack-on-relationship-with-assad-sources .

5. Jay Solomon and Carol E. Lee, “Obama Opens Troubled Talks With Gulf Allies”, Wall Street Journal, 13 May 2015, http://www.wsj.com/articles/obama-meets-with-saudi-delegation-ahead-of-u-s-arab-summit-1431534462 .

6. Moscow Changing Tack, Asharq Al-Awsat, 31 May 2015.

7. Hala Jaber, “Assad Begs Iran for More Help to Save Syria from ISIS Scourge”, Sunday Times, 7 June 2015, http://www.thesundaytimes.co.uk/sto/news/world_news/Middle_East/article1565580.ece.

8. Ibrahim Humaidee, “Iran Wants ‘Sovereign Guarantees’ in Exchange for Shoring Up Syrian Regime” [Arabic], al-Hayat, 3 February 2015, http://alhayat.com/Articles/7162986/%D8%A5%D9%8A%D8%B1%D8%A7%D9%86-%D8%AA%D8%B7%D9%84%D8%A8--%D8%B6%D9%85%D8%A7%D9%86%D8%A7%D8%AA-%D8%B3%D9%8A%D8%A7%D8%AF%D9%8A%D8%A9--%D9%84%D9%85%D9%88%D8%A7%D8%B5%D9%84%D8%A9-%D8%AF%D8%B9%D9%85-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%86%D8%B8%D8%A7%D9%85.

9. Majid Rafizadeh, “Bashar al-Assad: A Costly Card for Iran?” Al-Arabiya, 11 April 2014, http://english.alarabiya.net/en/views/news/middle-east/2014/04/11/Bashar-al-Assad-a-costly-card-for-Iran-.html.

10. Adnan Ali, “Assad Asks Moscow for Political Lifeline” [Arabic], al-Araby al-Jadeed, 6 June 2015, http://www.alaraby.co.uk/politics/2015/6/5/%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A3%D8%B3%D8%AF-%D9%8A%D8%B3%D8%AA%D9%86%D8%AC%D8%AF-%D8%A8%D9%85%D9%88%D8%B3%D9%83%D9%88-%D8%B3%D9%8A%D8%A7%D8%B3%D9%8A%D8%A7.

11. Oliver Wright, “G7 Summit: President Assad Could Face Exile in Russia and the West's Plan to Tackle ISIS in Syria”, The Independent, 8 June 2015, http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/middle-east/g7-summit-president-assad-could-face-exile-in-russia-and-the-wests-plan-to-tackle-isis-in-syria-10305824.html.