There is more than on irony behind Vladimir Putin’s hold on power in Russia over the last 20 years in his posts as president and prime minister. He has taken local and foreign observers in Moscow by his call for “sweeping constitutional changes that could extend his hold on power indefinitely.” (1) Since his State-of-the-Union address January 15, 2020, Putin has pushed Russian politics into a state of bewilderment and uncertainty. One of his former prime ministers who has turned into a fierce critic, Mikhail M. Kasyanov, said the president had given a “clear answer” to questions about his future: “I will remain president forever.”

There has been growing debate about the gulf between what President Vladimir V. Putin says and what happens in Russia. Putin’s intentions have raised a fundamental question about the nature of his rule after more than 18 years at the pinnacle of an authoritarian system, writes Andrew Higgins, Moscow correspondent for The New York Times. (2) Some critics have questions Putin’s pursuit of unrivaled political longevity at the Kremlin, and his recent address amounts to a counterrevolution against Russia’s democracy. Dmitri Smirnov, a Kremlin reporter for the Komsomolskaya Pravda newspaper, said “Why has this all happened in a single day?” His answer: “It just means that those in Kremlin know history well: revolution has to be made swiftly, even if it’s a revolution from above.” However, other observers have been less wary of the Putin factor in Russia’s transformation. Ekaterina Schulmann member of Mr. Putin’s Council for Civil Society and Human Rights, said Putin’s grip on the country “had been vastly exaggerated by both supporters and opponents.”

In this paper, Mark N. Katz, professor of government and politics at George Mason University in Washington assesses the significance of Putin’s ambitions towards 2024 and beyond. He also probes into whether the idea of amending the Russian constitution to eliminate term limits on the presidency would remain a challenge.

The constitutional and government personnel changes that Russian President Vladimir Putin introduced in January 2020 suggest that he plans to remain in charge of Russia after the end of his current term as president, which is due to expire in 2024. Yet it is not clear how he plans to do so, for how long, and what his eventual plan for succession—if any—actually is.

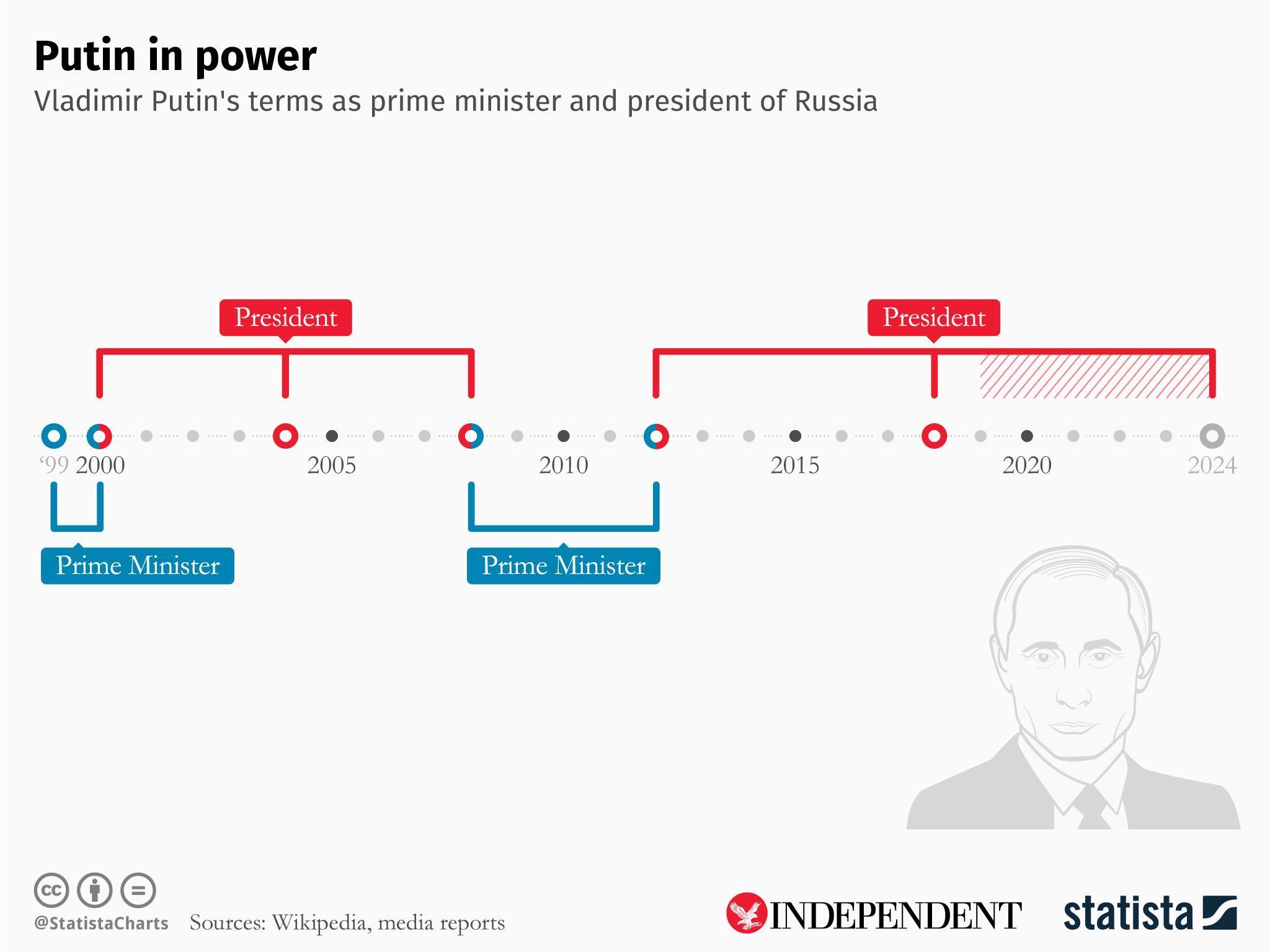

The current Russian constitution requires that the individual serving as president be limited two consecutive terms. Vladimir Putin complied with this provision after serving his first two terms (which then lasted four years) as president by stepping down from this office in 2008 and serving as prime minister during the one-term presidency of his hand-picked successor, Dmitri Medvedev. Putin, though, was elected president again in 2012 and 2018 (the term of the Russian presidency was extended to six years beginning in 2012), and so is now due to step down at the end of his second set of two consecutive terms which ends in 2024.

It has long been expected, though, that Putin would seek to remain in charge of Russia even while complying with the Russian constitution’s requirement that he step down, just as he did in 2008 when he became prime minister during the Medvedev presidency but was clearly still in charge. But how this would occur remained unclear. There was speculation that he and Medvedev (who became Putin’s prime minister again in 2012 after stepping down from the presidency) would trade places once again in 2024. There was also speculation that Moscow would push for the union of Russia and Belarus in order to allow Putin to become head of the union while someone else became president of Russia. Finally, there was always the possibility that the Putin-controlled Russian legislature would simply amend the constitution to eliminate term limits on the presidency and thus allow Putin to run again for as many more terms as he pleased.

Putin Faces the Nation

In his State-of-the-Nation address on January 15, 2020, though, Putin indicated that while he does intend to remain in charge, it would not be like he did before in 2008-12 or by any of the other means that there has been speculation about. Instead, Putin outlined a set of surprise constitutional amendments he was proposing (and which the Kremlin-controlled legislature is highly likely to approve) that together are seen as enabling him to remain in charge. (3) These amendments include limiting the presidency in future to two terms total (i.e., not just to two consecutive terms); making the State Council, which is currently an advisory body, an official governing body; and granting the parliament the right to appoint the prime minister and other minister (something the Russian president has done up to now). The president, though, will have the right to request that the Constitutional Court review draft laws before he or she signs them, and the right to propose to the Senate that Constitutional and Supreme Court judges be dismissed for being “dishonorable.” (4)

Immediately after this announcement, Prime Minister Medvedev and the entire cabinet tendered their resignations. While he would soon reappoint most ministers in their existing positions, Putin accepted Medvedev’s resignation, appointed a technocrat to replace him, and offered the increasingly unpopular Medvedev the newly created post of deputy chairman of the Security Council (which Putin, as president, is chairman of). (5) The Russian Duma has already begun the process of approving Putin’s constitutional amendments. Once this is completed, they are to be voted on by the Russian public sometime in the spring of 2020. (6)

As with some of Putin’s previous major moves (such as trading places with Medvedev in 2008, doing so with him again in 2012, and seizing Crimea in 2014), Putin’s January 2020 announcement about constitutional changes has caught the world off guard. However while there is a general consensus that these constitutional amendments will allow Putin to remain in charge past 2024, it is still not clear how he plans to do so.

One possibility that appears to be unlikely is that Putin will become president for a fifth term. Not only would the new stricter term limits on the presidency rule this out, but the fact that the presidency will be a weaker position than it has been up to now suggests that it would not be of interest to Putin. On the other hand, there has been speculation that Putin will “restart the clock” in 2024 on the absolute limit of two terms as president, thus enabling him to stay on until 2036.

Another possibility which observers have discussed is through Putin becoming chair of the more powerful State Council that he has proposed. This position would free him from day-to-day governing, but allow him to retain a veto over any policy he disapproved of being pursued by the president or prime minister—much in the way that Nursultan Nazarbayev is believed to exercise control in Kazakhstan through remaining chairman of the Security Council and being designated “Leader of the Nation” after he stepped as president in 2019.

A Déjà Vu Prime Minister?

What is confusing about Putin’s constitutional changes, though, is that the Russian president, despite being weakened, is supposed to appoint the members of the State Council. Perhaps, though, Putin plans to make these appointments himself before he steps down, or feels confident that whoever the next president is will make the appointments Putin wants him to make. Less clear is how long the chair and members of the State Council will be appointed for, and how or even whether they can be removed from office.

Another possibility still is that Putin can follow the precedent he set in 2008 of becoming prime minister once again after leaving the presidency. Indeed, with the new constitutional amendment, Putin becoming prime minister could put him in a constitutionally stronger position than he was while serving in this position in 2008-12. Back then, President Medvedev appointed him as prime minister and had the right to dismiss him at any time (even though Medvedev could probably not have even tried to do so and survived). With the Russian prime minister now to be appointed by the Duma, Putin can remain prime minister as long as he controls a majority in it. And this is something he may be able to do indefinitely, as there is no term limit on the prime ministership.

Finally, there is the possibility that Putin could remain the ultimate arbiter of Russian politics without holding any official post; much like Deng Xiao-ping did in China in his later years. After serving as Russia’s top leader for so long, Putin may well now be in a position where he can successfully do this since the personnel in the system he has created are more loyal to him than to anyone whom he allows to become president or prime minister.

Which of these routes for retaining power and influence after his current term as president ends will Putin take? So far, Putin has not said. He could take any of the paths identified here, or some other one altogether in the sort of surprise move he appears to take delight in. Indeed, he could take them all in turn in the years ahead—such as first resuming the prime ministership, then becoming chair of the State Council for a period, and then becoming something akin to Deng Xiao-ping (the Deng Xiao-Putin option) after that. He could even have the constitution amended yet again to add back the powers he is now in the process of taking away from the Russian presidency as well as to allow him to resume the office.

The most curious aspect of Putin’s January 15 State-of-the-Nation address in which he announced these constitutional amendments is that he appeared to be announcing (or, some might say, confirming) that he intends to retain power after his current term as president ends, but he did not state clearly how he intends to do so. This may be either because he himself has not decided on what course of action he will take, because he has decided but prefers not to announce his plans until later, or because he just prefers to keep his options open until the last moment. And there may be good reason for such hesitancy: Putin’s plans to retain power may not be popular in Russia.

For many in Russia, Putin’s late 2007 announcement that he would support Dmitri Medvedev to become president in 2008 was welcome because it appeared to signal that Putin was actually stepping down and that he was allowing the transfer of power to a younger generation. Of course, doubt was quickly cast upon such hopes when immediately after he was sworn in as president, Medvedev appointed Putin as prime minister. Yet hopes for eventual change remained with the prospect that Medvedev would run for a second term, and that he might appoint a new prime minister. But any such expectations were dashed in September 2011 when Medvedev announced that he and Putin (actually, just Putin) decided to switch places once again with Putin resuming the presidency and Medvedev the prime ministership. (7)

Soon thereafter, major demonstrations lasting for months broke out against Putin. Even though Putin’s party lost many seats in the December 2011 Duma elections, Russian protesters were convinced that it had actually lost its majority. Putin himself stated—and may have actually believed—that the demonstrations against him erupted as a result of a “signal from Hillary Clinton,” who was then Barack Obama’s Secretary of State. (8) Moscow, of course, was able to quell the demonstrations and Putin won the 2012 presidential election. But this was arguably the most vulnerable moment in Putin’s long reign, whether as president or prime minister—one that he does not wish to see repeated. Yet his own statement after winning his fourth term in 2018 that he did not intend to run again for president in 2024 (9) may have once again raised expectations for change.

Age of Putinian Theatrics?

Thus, Putin’s January 2020 announcement about constitutional changes combined with his indication that he will somehow stay on but without specifying how may be intended not just to prepare the Russian public for his continuing to play a powerful role in Russian politics, but also for testing the waters about what might be the most acceptable (or just the least unacceptable) method for him to do so. The upcoming vote by the electorate on his constitutional changes once they have been approved by the Russian legislature (about which there is little doubt) may be viewed by the Kremlin as a means of rallying popular support for them as well as an early indicator of what the public will accept with time for revisions before the next presidential elections that are due in March 2024, if necessary.

The key for Putin in containing public opposition to his remaining in power indefinitely may be to create a sufficient degree of political theater in which various actors—president, prime minister, State Council chair, Constitutional Court judges, and members of parliament—are all seen to play somewhat contending roles even if Putin is the ultimate arbiter among them. And even if the Russian public becomes largely resigned to the fact that Putin will remain in charge, the increased role of these other actors may give rise to the hope that a post-Putin era—perhaps even a democratic one—may be in the process of emerging. This could even be Putin’s plan: as he ages, his continued security and prosperity might be far better ensured through yielding power to a more democratic polity that he retains important levers over than by succeeded by a strong authoritarian figure like himself who could (and, Putin may worry, probably would) eventually deprive him of his influence and wealth.

This scenario may not be farfetched. Indeed, something like this was advocated by Andranik Migranian at the outset of the post-Soviet era. He argued then that the best path forward for Russia was to undergo economic transformation under modernizing authoritarian rule since this economic transformation would be difficult and unpopular, and hence impossible for a democratic government to undertake. It is only after economic modernization has occurred that authoritarian rule could safely give way to democratization. Positive examples of this which Migranian cited were the economic growth experienced by Chile under Pinochet and South Korea under military rule before their democratic transformations. (10)

Still, even if Putin eventually has something like this in mind, it is far more likely that he sees the need for the “temporary” period of authoritarian guidance (especially with himself providing it) as needing to continue rather than ready to end. Indeed, in the medium term, what Putin may be more focused on is devising a system whereby he remains in control but frees himself of the burden of day-to-day administration. This, however, is not a new objective for him, but one he has attempted—and failed—to achieve in the past.

As Fiona Hill and Clifford Gaddy described in their book, Mr. Putin: Operative in the Kremlin, Putin envisioned his preferred system of governance—“the vertical of power”—as one in which trusted and capable subordinates would be able to deal effectively with the many different problems that Russia faced. The president (Putin) would thus not need to become involved in the nitty-gritty of dealing with them, but could just make sure that his subordinates did so effectively. The problem with this vision, as Hill and Gaddy pointed out, is that it never met Putin’s expectations. Either his subordinates made decisions that he did not like, or fearing his wrath, avoided making any decisions. The result was that whenever serious problems occurred, Putin himself would have to become involved in the details of policymaking if they were to be resolved to his liking. (11)

It has even been reported that Putin’s decision to resume the presidency from Medvedev in 2012 occurred as a result of his disapproval of Medvedev’s Libya policy in 2011. Instead of vetoing the UN Security Council Resolution authorizing a no-fly zone over eastern Libya to protect Qaddafi’s opponents, Medvedev ordered Russia to abstain on the resolution (as did China), thus allowing it to pass. The U.S. and its allies, though, did not just impose a no-fly zone, but actively intervened in support of Qaddafi’s adversaries, who eventually captured and killed Qaddafi. Consumed as they then were by the desire to avoid “another Rwanda,” it is uncertain whether Obama and his top advisors would have refrained from intervening in Libya even if there had not been a UN Security Council Resolution authorizing a no-fly zone in Libya (Obama’s subsequent decision not to intervene in Syria may have resulted less from the inability to obtain a similar resolution than his disillusionment over the results of intervention in Libya). And Putin may have decided on resuming the presidency even if the Arab Spring not occurred. But the combination of Medvedev pursuing a Libya policy that Putin judged to be ill-advised may well have convinced him that he could not leave such important matters to subordinates, but had to retake control of matters himself. (12)

If so, the question that arises is what will Putin do if a similar situation arises after his current term ends and all the changes he is making come into being? Will he be content to give advice, but allow the new players to make decisions that he disapproves of? Or will he retake control from the protégés whom he has lost confidence in? The confusing system that the constitutional changes he has introduced certainly may give him far more opportunity, from whatever position he ends up in, to sideline officials he disagrees with than during the 2008-12 “tandemocracy” when Putin had to wait for Medvedev’s term as president to end before resuming the post himself.

However, his sidelining and removing a president or prime minister he disagrees with will lead back to the familiar problem of Putin having to manage everything himself because his subordinates will be too frightened of being second-guessed by him. And unless Putin can portray himself as being more in tune with Russian public opinion than the subordinates he has allowed to obtain important political posts, then his seizing control over policy issues from them risks raising the issue of his legitimacy as well as undermining the system he is seeking to create.

Political Eternity!

Of course, Putin may not actually be trying to create a new system to take over from him, but simply creating a system that will allow him to retain control. Yet sooner or later (possibly much later), he will be forced to relinquish control either by old age and infirmity or simply by mortality. This may leave his successors, though, in a difficult position. Just as the Soviet-era Russian constitution inherited by Yeltsin after the collapse of the Soviet Union was never intended to outline how a government should operate and so helped create the 1993 constitutional crisis in which Yeltsin used force to shut down the Russian parliament: if the purpose of Putin’s 2020 constitutional changes is to ensure that he can remain in control indefinitely and not serve as the actual basis on which the Russian government will operate, then a similar confrontation could arise between different officials referring to different parts of the Putin-amended constitution as justification for why they should prevail over their rivals. And there is always the possibility that the same kind of deal that Yeltsin made with Putin in 1999 (relinquishing the top leadership position to him in return for living out his life in peace and security) will be made by Putin with someone similar.

The main takeaway, then, about the constitutional and personnel changes that Putin introduced in January 2020 is that while they indicate that Putin plans to remain in charge after the end of his current term as president, it is not clear how he plans to do so, for how long, and what his eventual plan for succession—if any—actually is. All that is really known is that he plans to remain in charge indefinitely. And that is not really news.

- Andrew Higgins, “Russian Premier Abruptly Quits Amid Swirl of Speculation on Putin”, the New York Times, January 15, 2020 https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/15/world/europe/medvedev-putin-russia.html?action=click&module=Top%20Stories&pgtype=Homepage

- Ibid

- Tatiana Stanovaya, “Russia Prepares for New Tandemocracy,” Carnegie Moscow Center, 20 January 2020, https://carnegie.ru/commentary/80838?utm_source=rssemail&utm_medium=email&mkt_tok=eyJpIjoiWWpKbFpHRmxZVGcwWkdVMyIsInQiOiJNMCtYOVhmRnY0d25oNFprNHJwMGVJRis4OHBINTVBM3hRWWpGZHNRUHQzcU9mXC9lUVBcL3VzWWFOWjlmYmNkeWI4NitQb2lXYUdOa0U1QWhvNmk2RXY2TWx5NGJKcitGYUhQYk55TkRDeE5ZZ0dYbjR2N1Ntcmpxeit1REgxaTZMIn0%3D

- “What Changes Is Putin Planning for Russia’s Constitution?” The Moscow Times, 16 January 2020, https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2020/01/16/what-changes-is-putin-planning-for-russias-constitution-a68928

- “'Not Everything Works Out': Medvedev's Career, in Photos,” The Moscow Times, 16 January 2020, https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2020/01/16/not-everything-works-out-medv…; (accessed 24 January 2020); “Who Made It Into Russia’s New Cabinet?” The Moscow Times, 22 January 2020, https://www.themoscowtimes.com/2020/01/22/who-made-it-into-russias-new-cabinet-a69004

- Emily Sherwin, “Russian Parliament Fast-tracks Putin's Constitutional Changes,” dw.com, 23 January 2020, https://www.dw.com/en/russian-parliament-fast-tracks-putins-constitutional-changes/a-52106277

- Fiona Hill and Clifford G. Gaddy, Mr. Putin: Operative in the Kremlin, new and expanded edition (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2015), pp. 192-95.

- Ibid., p. 235.

- Harriet Agerholm, “Vladimir Putin Says He Will Step Down as President in 2024,” The Independent, 26 May 2018, https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/vladimir-putin-russia-step-down-president-2024-a8370361.html

- Russell Watson, “An Authoritarian Solution?” Newsweek, 16 June 1991, https://www.newsweek.com/authoritarian-solution-204458 (accessed 24 January 2020); and Martin Sieff, “Markets First, Elections Later,” The American Conservative, 19 June 2012, https://www.theamericanconservative.com/articles/markets-first-elections-later/

- Hill and Gaddy, Mr. Putin: Operative in the Kremlin, pp. 209-12.

- Angela E. Stent, The Limits of Partnership: U.S.-Russian Relations in the Twenty-First Century (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2014), p. 248; and Brian D. Taylor, The Code of Putinism (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018), p. 182.