On the 3rd of January 2020, the United States signalled its intent to escalate tensions with Iran, through the assassination of Qasem Soleimani, the commander of Iran’s Quds forces, in Iraq. Following attacks from Iranian-backed Iraqi Shia militia on the American embassy in Baghdad, the escalation took place on a backdrop of worsening US-Iranian relations, focused on the US withdrawal of the Iranian nuclear deal (and Iran’s subsequent rollback of key commitments), the reinstatement of economic sanctions against Iran, and increasing tensions in the Straits of Hormuz. Such tensions have been met with concern in East Asia, particularly among countries that have been steadily expanding their relationships with Iran. Responses, however, reflect a continuation of business as normal rather than any great change.

While Malaysia, for example, has condemned the assassination in line with their growing closeness to Iran, there has been no tangible change of policy. Indonesia, who has developed a relationship but emphasised their desire to remain neutral in the Iran-Saudi tensions, have avoided making overt statements in support of Iran or condemning US action. For the most part, therefore, Southeast Asian states have been unwilling and unable to abandon their relationship with the US and other key states such as Saudi Arabia, or isolate themselves by supporting Iran overtly.

For other East Asian states, overtly supporting Iran runs the risks of encouraging the escalation of the conflict and the damaging of their interests, such as is the case with China. As such, this paper will argue that while the perception surrounding Soleimani’s assassination among East Asia is for the most part negative, this will not fundamentally impact on their relationship with the US or spur a further shift to Iran. Instead, in the face of continuing US pressure on Iran, Iran’s relationships within East Asia have begun to ultimately suffer.

This paper will begin by analysing the expansion of Iran’s relationship with East Asian states before going on to argue how these are likely to decline in future despite these countries’ concerns of US actions as well as actions of other important states such as Saudi Arabia. While Iran has expanded its relationship with a number of partners in East Asia, this paper will focus on relationships Iran finds particularly important. Primarily, this is Malaysia and Indonesia, who, as countries with Muslim majority populations, have seen their involvement with Iran growing at a faster pace than others but in relationships mired in complexity. It will also consider China’s perspective; a relationship that has taken on importance for different reasons.

Iran’s relationships in East Asia have fluctuated over the past four decades following the Islamic revolution in Iran in 1979, but have generally grown – especially since the 2005 ‘Look to the East policy’ that prioritised relations with Asia (Sahriatinia 2011; Liu and Wu 2018). Seeking to find partners outside of the West, Iran saw Malaysia not only as a country in which it could trade, but also an opportunity to demonstrate it could engage with the wider Sunni Islamic world despite being Shia, improving its image (Razak 2017). The relationship was, however, limited by concerns over Iran’s revolutionary rhetoric and their Shia beliefs, something increasingly policed and rejected in Malaysia (Shanahan 2014; Osman 2016; Abu-Hussin, Idris & Salleh 2018).

Instead, the relationship with Iran was, in the beginning, tied up with domestic politics regarding intra-Malay rivalries between more moderate UMNO, and more conservative PAS political parties, both who claimed to represent the Muslim Malays (Nair 1997). As PAS are more conservative, links with Iran were especially important to bolster their Islamic credentials in the midst of an Islamic revolution while Mahathir’s party UMNO was increasingly questioned on its ability to protect the Islamic Malays’ position in Malaysia as it attempted to portray itself as a moderate actor with its Malay-Muslim electorate (Nair 1997).

Iran ‘Looks East’

Significantly, current political leaders such as Anwar Ibrahim, then-President of Islamic NGO Angkatan Belia Islam Malaysia (ABIM), took the lead and visited Ayatollah Khomeini shortly after the revolution (Nair 1997). During this period Mat Sabu, now Defence Minister but at the time a member of PAS, also visited Iran, and has been accused of being extremely close to the country (with some accusing him of being Shia himself, though this is something that has been heavily disputed) (Carvalho 2013; Abu-Hussin, Idris & Salleh 2018).

Also of significance is that it was also under Mahathir, Prime Minister from 1981-2003 and now again, that ties were able to expand, though only after intra-Malay unity was no longer under threat and, significantly, Ayatollah Khomeini died – bringing forth the potential for more moderate Iranian leadership. Iran then provided an opportunity for his essentially anti-colonial and anti-Western ‘Buy British Last’ and ‘Look East’ and policies into practice (Idris & Yusoff 2015; Razak 2017). These policies aimed at towards the rejection of depending on Western economic ties and seeking alternative visions of modernisation amongst the so-called Asian ‘tigers’ such as Japan (Chong & Balakrishnan 2016; Wain 2009).

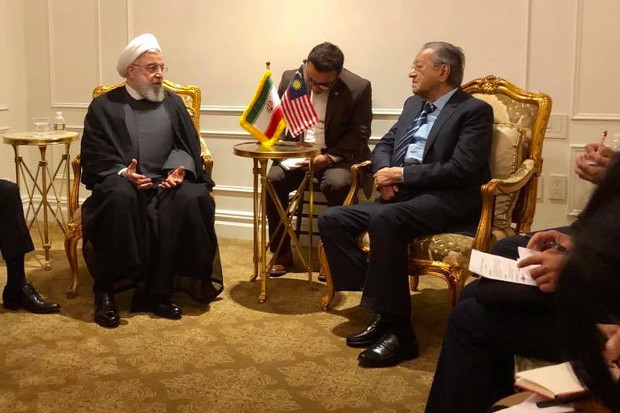

Such complementary goals led to an increasing exchange of relations – including Mahathir’s own visit to Iran in 1993 (Ali 1984; Nair 1997; Idris and Yusoff 2015). Since then, Iran’s requirement to seek Eastern engagements to Western pressure has led to a great deal of consistent rhetoric concerning the relationship in the “Look East” policy (Soltaninejad 2017). An example can be seen in former-Foreign Minister Veleyati’s emphasis on deepening ties in 2016 (Tehran Times 2016).(1)[i] Much of the ties, however, were economic in nature. Even though Malaysia adhered to the Iran-Libya Sanctions Act from 1996 it did not stop trading oil with Iran, and continued joint investment in gas projects (Abu-Hussin, Idris & Salleh 2018). There have been various Iranian investments in Malaysian refineries, as well as joint developments. Significant non-petroleum industries are the export of palm oil to Iran, increasingly important in the face of EU plans to ban palm oil from biofuels meaning Malaysia needs to maintain markets elsewhere (Ooi 2017; Kumar 2019).

This shift has led to Iran counting for 20 per cent of Malaysia’s total trade with Middle Eastern countries, the third largest share behind the UAE and Saudi Arabia (Idriss & Yusoff 2015). While Malaysia continues to crackdown on Shiism, sources estimate there are between 100,000 and 200,000 Iranians studying or working in Malaysia (Idris & Yusoff 2015; Kamal & Hossain 2016; Sedgley 2012). Malaysia has been careful to not take too bold an action in terms of Iranian influence on Shia believers and Iran, for its part, has mostly ignored Malaysia’s repression of the Shia population (Shanahan 2014; Idris and Yusoff 2015; Abu-Hussin, Idris & Salleh 2018).

There were, however, some limitations to the development of the relationship that seem to be reversing currently. As Abu-Hussin, Idris and Salleh (2018) argue, any attempts to widen the relationship beyond economics is politicized due to the religious cleavages, and this was particularly the case under Najib’s tenure. Malaysia’s treatment of the Shiites, while not met with an official Iranian response, led to some Iranian businessmen to boycott Malaysian goods (Sulong 2014).

Under Najib, Malaysia also grew closer to Saudi Arabia, a difficult balance to maintain in the context of Iranian and Saudi opposing influence in the Yemeni civil war (Edwards and Malik 2018). Malaysia welcomed a visit from King Salman, and this was reciprocated by a high-profile trip to Saudi Arabia by Najib (The Star 2017; The Star 2018). This culminated in significant economic investment and growing security ties. This manifested in the joint anti-terrorism King Salman Center for International Peace (KSCIP), for which Saudi Arabia provided the funding, and Malaysia’s joining of the Saudi-led coalition in joint operations from Riyadh, seen by some as a military bloc against Iran and supporting Saudi intervention in Yemen (Bowie 2017; Edwards & Malik 2018).

As the relationship grew, so too did concerns over the “Arabization” of Malaysian Islam, particularly Wahhabism becoming more prominent in Malaysia and influencing its governance (Bowie 2017; Free Malaysia Today 2017; Malik and Edwards 2018a). This deepening relationship, that came at the expense of the Iranian relationship, alongside sanctions resulting from Iran’s nuclear ambitions (which led to it being branded part of the so called ‘axis of evil’) led to a decline in trade – including, temporarily, the halting of gas exports to Iran (which Mahathir disagreed with publicly) (Kaur 2013).

Interestingly, those who advanced the Iranian relationship in the past have returned to power, seeing a degree of reversal (Edwards 2018a; Edwards and Malik 2018). By withdrawing troops from Saudi Arabia and closing the KSCIP, Mahathir seemed to signal that the relationship with Saudi Arabia would not dominate and they would attempt to revert to a more neutral outlook (Edwards and Malik 2018). Indeed, Malaysia’s relationship with Saudi Arabia has soured to some degree, with Mahathir being vocally critical of the Saudi-led Organisation of Islamic Cooperation and concerns of Saudi willingness to be an alibi for Najib’s alleged corruption in the 1MDB affair (Edwards 2018b; Chin 2020).

There is no greater sign of this, it has been argued, than the Islamic Conference organised in Kuala Lumpur that was aimed at boosting Muslim unity, but was seen as a clear signal to Saudi Arabia as it included three of their rivals, including Iran, and has been analysed as an attempt to replace the OIC (Izzuddin 2020). Mahathir has also expressed his intent to deepen ties with the ‘Development 8’, an organisation that includes Iran. Such signals are seen as significant in the face of Saudi-Iran tensions and involvement in the Yemeni civil war, marking a shift in Malaysia’s policy away from Saudi Arabia towards a more balanced, if not Iran-friendly, posture.

Indonesia, too, has seen a growing relationship – though this has been much more modest, focused on the economy, and not, it would seem, to be driven by elites as Malaysia’s policy has been. Indeed, following the Islamic revolution van Bruinessen (2013) argues that there was a growth in Sunni to Shia conversion, though Iran was careful not to be seen as openly supporting this dynamic, which culminated in a strong Saudi ‘counteroffensive’ and a growing Salafi movement within the country (Hasan 2018). Despite this, then-President Suharto was unwilling to allow religious ideology to strongly influence Indonesia’s foreign policy (Anwar 2010b).

Instead, Suharto had declined joining the Organisation of the Islamic Conference on the grounds that Indonesia is not an Islamic state, and such caution was exercised following the Islamic revolution when it remained neutral in the face of US-Iranian tension and the outbreak of war between Iran and Iraq, where Suharto rejected the idea of being a mediator (Anwar 2010b; Sukma 2003). For Iran, however, Indonesia has always held importance as Indonesia is the most populous Muslim country, meaning gaining favourable relations advances Iran’s desire to engage with the wider Muslim world and improve its image considerably (Ravi 2019).

It was only in the late 1980s that Suharto began to focus more on the Islamic world, as a result of declining support and the need to appease Muslim groups (Anwar 2010a; 2010b; Sukma 2003). In 1990, then-Minister of trade Siregar visited Iran, resulting in a Memorandum of Understanding on trade, with an increasing exchange of officials culminating in Rafsanjani visiting Indonesia in 1992 and Suharto visiting Iran shortly after (Sukma 2003). This pattern has mostly continued consistently. Similar to Malaysia, much of the relationship has been focused primarily on petroleum, with investment to develop refineries being a key example, and has been institutionalised in the D8 grouping.

Also similar to Malaysia, there have been tensions in balancing Iranian and Saudi influences in particular, and enduring US pressure to limit relations with Iran. Indonesia signed a defence cooperation agreement with Saudi Arabia under the Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono (SBY) administration, and King Salman also visited Indonesia with a delegation of 800 people, bringing the promise of closer ties and an increase in investment (Edwards and Malik 2018). While this has been marred recently by the executions of Indonesian workers, bringing greater scrutiny on the treatment of the many domestic workers in the Kingdom more generally, there has not been a significant stalling of relations, and Indonesia has aimed to remain relatively neutral in the Iran-Saudi conflict. In part this may be a result of the Shiite and Sunni divide, as while Shiism is not banned in Indonesia as it is in Malaysia, there have been tensions (Ravi 2019). Saudi funding of education in Indonesia, through generous scholarships and the funding of LIPIA, has deepened this divide as Wahabi and Salafi politicians are increasingly gaining influence in Indonesian politics (Malik and Edwards 2018a). Despite this, Indonesia has been vocal about its desire to remain neutral, and expand relations gradually with both countries.

In contrast to Malaysia, therefore, Indonesia’s recent relationship with Iran has not been quite as developed by elites. As mentioned, Indonesia has expressed its desire to remain neutral. Furthermore, US pressure and Indonesia’s desire to be a global power have also in the past limited their links with Iran. When Indonesia became a non-permanent member of the UNSC in 2007, for example, they supported Resolution No. 1747 imposing sanctions on Iran, despite rejecting condemnation of Iran’s words about Israel’s disappearance and calling the nuclear program peaceful (Biersteker and Moret 2015; Ravi 2019; Anwar 2010a; 2010b).

This decision faced backlash from the Indonesia public, however, who perceive the US as unfairly targeting a Muslim country (Anwar 2010a; 2010b). Such a decision was supported by DPR members who called SBY for questioning over the decision. Though he did not attend himself, the backlash led to Indonesia then abstaining from further votes concerning sanctions of Iran – demonstrating that the relationship does have importance, even if it is primarily for domestic reasons and trade (Anwar 2010a; 2010b).

While the focus of this paper is on Muslim majority states, due to their more extensive ties with Iran, it is worth noting that Iran’s ‘Look East’ policy has had a tangible impact on relations with other East Asian states that impact on Asia’s perspectives of Us-Iran tensions. The Philippines, for example, has a Joint Economic Commission with Iran, and consultations are ongoing in an effort to expand ties further (Philippines Department of Foreign Affairs 2016; The Philippine Star 2018). Thailand has also expressed its desire to see trade with Iran increase, with petroleum once again highlighted, in light of Iran’s non-involvement in the South separatist movement - though this trade is currently declining (Yusof 2007; Vanaki 2017; Financial Tribune 2019).

China is also worth highlighting. As a country that has found itself in tensions with the US, Iran sees China as a potentially strong partner that could help in countering US pressure and there are shared concerns of US hegemony (Liu and Wu 2010; Patey 2006). China’s desires to be seen as a responsible world power, however, have prevented the emergence of a resilient relationship (Shariatinia 2011). China has supported sanctions against Iran, for example. Instead, the relationship has been limited as it is mostly centred on China seeing Iran as a source for crude oil imports, with extensive joint-developments and infrastructure investment, and requiring a stable Persian Gulf as a result of rising oil demand from the region (Shariatinia 2011; Leverett and Bader 2005; Dorraj and Currier 2008; Nyman 2018). This has since expanded since China’s focus on the Belt and Road initiative, where Iran has become a significant crossroad for China’s ‘Silk Road’ (Shariatinia and Azizi 2019). On the other hand, Iran has been a significant importer of Chinese military hardware, and a recent trilateral naval exercise drew commentary of growing defence linkages between the two countries (Swaine 2010).

The Effects of Soleimani’s Assassination

Through an analysis of improving, yet restrained, Iranian relationships with East Asian countries, it is no surprise that the immediate reaction to Soleimani’s assassination has been a mixture of indignation, calls for calm heads, and concern about US unilateral actions, the potential for conflict, and the potential economic cost. While immediate reactions have differed, however, there is a remarkably consistent policy reaction.

In line with the above analysis demonstrating Malaysia’s increasing closeness to Iran, it is no surprise that Mahathir has been perhaps the most vocal, describing US actions as being immoral (Sipalan 2020). Indeed, prior to this Mahathir signalled his unease at US sanctions, stating at an October meeting that ‘The US sanctions are not only against Iran but also against other countries, including Malaysia and we should seek to arrange for the development of cooperation…I always consider myself as Iran's friend’ (Iran Ministry of Foreign Affairs 2019). He has stated this on the side-lines of the 35th ASEAN summit, arguing that Malaysia itself Is being unlawfully sanctioned as ‘the sanctions don’t apply to one country alone’ (Free Malaysia Today 2019).

Responding to US pressure regarding sanctions, Malaysian banks began to freeze accounts held by Iranians – even though Mahathir has, once again, expressed his disdain for the sanctions when stating: ‘Our ties with Iran are very good. But we face some very strong pressure from certain quarters, which you may guess…a kind of bullying by powerful people.’ (The Star 2019). Importantly, however, Malaysia acquiesced to the sanctions and US pressure, demonstrating it is not willing to abandon its relationship with the US who is the only possible power that can contain China’s influence at a time of particular sensitivity regarding areas such as the South China Sea. In a seeming attack on Saudi Arabia, furthermore, Mahathir compared the assassination to the murder of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi. He called upon the Muslim world to unite, which, on the surface, suggests that Iran’s attempts to gain the support of the Muslim community is showing signs of success (Sipalan 2020; Chin 2020). Despite this rhetoric, however, Malaysia is remaining notably neutral in terms of its policies, and showing that it is not willing to jeopardise its relationships with Saudi Arabia in practice. Malaysia is cognisant of the fact that Saudi Arabia controls the quota for the Haj and has invested into their economy significantly.

Instead, Mahathir’s comments should be seen not as an indication of policy change, but a continued emphasis of focusing on the Muslim community in foreign policy rhetorically, if not always in practice. This addresses domestic political cleavages whereby he is under pressure to demonstrate that his new party Bersatu can represent Islam at a time the opposition UMNO is stressing its religious credentials and increasingly working together with PAS (Edwards 2018c; Malik and Edwards 2018b). While this rhetoric is particularly strong, what the Soleimani assassination has done is highlight the challenge of trying to maintain good diplomatic links with Iran, as well as the limits of Iran’s look east policy, even in cases where it was seemingly doing well.

Prior to the assassination, Indonesia’s downgrading of its delegation to the KL conference demonstrated that it would be unwilling to go against Saudi pressure. Indonesia, too, relies on Saudi for the Haj quota, and has also seen a strong recent investment incoming from the country. Instead, leaders and elites in Indonesia have avoided commenting in such a way that demonstrates any possibility of choosing a side, reflecting their continued desire to remain neutral. Instead, they limited their response to Foreign Minister Retno Marsudi summoning both ambassadors in Jakarta to encourage the US and Iran to ease the tensions (Antara 2020). This reflects a practical concern that tensions and instability could have a tangible impact on both Indonesia’s economy and their desire to remain neutral in the midst of escalating tensions. The immediate oil price rise of 1.4 per cent following the Iranian missile strike retaliation, for example, drove concerns that they would have to revise their annual budget, especially in the face of a weakened rupiah (Utama 2020).

Finally, China has demonstrated a policy with a mixture of dynamics similar to both Malaysia’s indignation and Indonesia’s desires to remain neutral and avoiding rhetoric that could have any part in escalating the conflict. The indignation was more apparent before the escalation of Soleimani’s assassination. China’s Foreign Minister Wang had, on the 1st of December 2020 stated that China will stand with Iran ‘against unilateralism and bullying’ in response to US pressure (Fulton 2020). Despite this, following the potential of escalation, his comments were much more measured, saying that ‘China pays high attention to the intensification of U.S.-Iran conflict, opposes the abuse of force in international relations, and holds that military adventures are unacceptable’ and focusing on how US military operations violate the norms of the international system (Panda 2020).

Such a measured response demonstrates Iran’s relative isolation, and highlights that China wishes to avoid any part in heightening instability in the Persian Gulf as it relies not only on Iran but also Iran’s Gulf rivals. China’s energy requirements are not fulfilled by Iran alone, and while Iran has become strategically important so too have other states such as Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Oman and Kuwait. Instability threatens the Straits of Hormuz, through which much of China’s imports travels. The expansion of the Belt and Road also depends on an area of maximum stability.

In line with other East Asian states which prioritise their relations with the US, furthermore, China is also choosing to avoid further strain in their relations in order to maintain stability and end the trade war (Chandran 2020). This reflection of a more general concern over the impact of US-Iran tensions can also be seen in other East Asian states, particularly Thailand and the Philippines who both began planning for the evacuation of citizens from Iran and Iraq, as well as for the potential for Iran-sympathetic groups to carry out attacks within the two countries, as had happened in Bangkok in the targeting of Israeli diplomats in 2012 (Lalu 2020; Boonbandit 2020).

Conclusion

Despite Iran’s growing relationships with key East Asian states in recent decades, the measured reactions to Soleimani’s killing and the growing escalation with the US demonstrates its isolation. For East Asian states, the assassination highlights the challenges of trying to maintain a strong and resilient relationship with Iran in the face of US pressure and the desire to remain neutral in the tensions. Indonesia especially highlights this issue, demonstrating that Iran will face great difficulties in uniting the Muslim world as its most populous country continues a stance of neutrality and a relationship based essentially on pragmatism and economic interests rather than any strong ideological stance. Instead, Indonesia has expressed its desires to advocate for a lessening of tensions in order to maintain stability and avoid economic affects of any potential conflict. Rather than advocating for any one-side in the divide in the Muslim world predicated on Iran and Saudi Arabia’s conflict, they have instead remained measured and, for the most part, been unwilling to risk their relationship with Saudi Arabia to advance it further with Iran.

More problematically for Iran, strong rhetoric from those that, on the surface, have goals in common with Iran has remained essentially hollow and short-lived. In Malaysia, a growing relationship at the same time as a declining one with Saudi Arabia has not been enough to influence any particularly strong change of policy or overt support following Soleimani’s assassination. Instead, it stems from an impassioned focus by Mahathir and an attempt to unify the Malay Muslim electorate under his new party Bersatu, which is yet to demonstrate its Islamic credibility to any strong degree – something which vocal support for a bullied Muslim partner on the world stage presents an opportunity. While the unity of the Muslim world is something focused upon by Mahathir, therefore, growing scrutiny of their relationship with Iran demonstrates the way in which they are unwilling to choose Iran over both the US and Saudi Arabia.

This general pattern, though for differing reasons, can also be seen in an analysis of China’s Iranian relationship and its reaction. While on the surface China has developed a strong relationship with Iran and has a goal in common, the decline of US hegemony, it is unable to support Iran without damaging its wider interests with other Gulf States and the US itself. Instead, China depends on a relatively stable Persian Gulf, and has therefore advocated for a more measured response. Iran’s relationships in East Asia, despite its Look East policy, remain relatively uni-dimensional, with all states focused primarily on its economic potential and energy resources, meaning that relationships resilient enough to withstand increasing scrutiny have not been developed.

Abu-Hussin, M. F., Idris, A., & Salleh, M. A., (2018) Malaysia’s Relations with Saudi Arabia and Iran: Juggling the Interests, Contemporary Review of the Middle East, 5(1): 46-64

Ali, A. (1984). Islamic revivalism in harmony and conflict: The experience in Sri Lanka and Malaysia. Asian Survey, 24(3): 296-313.

Antara News (2020) Indonesian Foreign Minister Marsudi summons US, Iranian ambassadors, Antara News, [Online] https://en.antaranews.com/news/139240/indonesian-foreign-minister-marsudi-summons-us-iranian-ambassadors (Accessed 23rd February 2020)

Anwar, D. F. (2010a) The Impact of Domestic and Regional Changes on Indonesian Foreign Policy, Southeast Asian Affairs, 126-141

Anwar, D. F. (2010b) Foreign Policy, Islam and Democracy in Indonesia, Journal of Indonesian Social Sciences and Humanities, 3:37-54

Biersteker, T., & Moret, E., (2015) Rising powers and reform of the practices of international security institutions, in: J. Gaskarth (Ed.) Rising Powers, Global Governance and Global Ethics (Routledge: Oxon)

Boonbandit, T., (2020) THAI GOV’T WORRIED FOR US-IRAN CONFLICT FALLOUT, Khaosod English, January 06 2020 [Online] https://www.khaosodenglish.com/politics/2020/01/06/thai-govt-worried-for-us-iran-conflict-fallout/ (Accessed 23rd February 2020)

Bowie, N., (2017) Malaysia’s ‘Arabization’ Owes to Saudi Ties, Asia Times November 25 2017 [Online] https://asiatimes.com/2017/11/malaysias-arabization-owes-ties-saudi-regime/ (Accessed 23rd February 2020)

Carvalho, M., (2013) Anwar Defends Mat Sabu in Syiah Issue, The Star Malaysia, [Online] https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2013/12/15/anwar-defends-mat-sabu/ (Accessed 23rd February 2020)

Chandran, N., (2020) What do tense US-Iranian relations mean for China, North Korea?, Al Jazeera, January 13 2020, [Online] https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2020/01/tense-iranian-relations-china-north-korea-200113043519574.html (Accessed 23rd February 2020)

Chin, J., (2020) Soleimani killing tests Iran's ties with Malaysia and Indonesia, Nikkei Asian Review January 07 2020, [Online] https://asia.nikkei.com/Opinion/Soleimani-killing-tests-Iran-s-ties-with-Malaysia-and-Indonesia (Accessed 23rd February 2020)

Chong, A., Balakrishnan, K. S., (2016) Intellectual iconoclasm as modernizing foreign policy: the cases of Mahathir bin Mohamad and Lee Kuan Yew, Pacific Review, 29(2): 235-258

Dorraj, M., & Currier, C. L., (2008) Lubricated with Oil: Iran‐China Relations In a Changing World, Middle East Policy, 15(2): 66-80

Edwards, S., (2018a) Malaysia’s first new government in six decades revels in a shocking victory, The Conversation, May 10 2018, [Online] https://theconversation.com/malaysias-first-new-government-in-six-decades-revels-in-a-shocking-victory-96369 (Accessed 23rd February 2020)

Edwards, S., (2018b) Malaysia’s Elections: Corruption, Foreign Money, and Burying-the-Hatchet Politics, Al Jazeera Centre for Studies, June 10 2018 [Online] https://studies.aljazeera.net/en/reports/2018/06/malaysias-elections-corruption-foreign-money-burying-hatchet-politics-180610090147666.html (Accessed 23rd February 2020)

Edwards, S., (2018c) Malaysia 2016-2018: An uncertain and incomplete transformation, Asia Maior, 29: 155-192

Edwards, S., & Malik, A., (2018) Saudi Arabian Relations Under Strain in Southeast Asia, The Diplomat, November 7 2018 [Online] https://thediplomat.com/2018/11/saudi-arabian-relations-under-strain-in-southeast-asia/ (Accessed 23rd February 2020)

Free Malaysia Today (2017) Marina: Saudis to blame for Malaysia’s ‘Arabisation’, loss of local culture Free Malaysia Today November 25 2017 [Online] https://www.freemalaysiatoday.com/category/nation/2017/11/25/marina-saudis-to-blame-for-malaysias-arabisation-loss-of-local-culture/ (Accessed 23rd February 2020)

Free Malaysia Today (2019) Malaysia being sanctioned, can’t trade with Iran, says Dr M, Free Malaysia Today, November 03 2019, [Online] https://www.freemalaysiatoday.com/category/nation/2019/11/03/malaysia-being-sanctioned-cant-trade-with-iran-says-dr-m/ (Accessed 23rd February 2020)

Financial Tribune (2019) Iran's Trade With Thailand Declines, Financial Tribune, July 15 2019 [Online] https://financialtribune.com/articles/domestic-economy/98940/irans-trade-with-thailand-declines (Accessed 23rd February 2020)

Fulton, J., (2020) China’s response to the Soleimani killing, Atlantic council, January 06 2020, [Online] https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/menasource/chinas-response-to-the-soleimani-killing/ (Accessed 23rd February 2020)

Hasan, N., (2018) Salafism in Indonesia, in: R. W. Hefner (Ed.) Routledge Handbook of Contemporary Indonesia (Routledge: Oxon)

Idris, A., Yusoff, R., (2015) Malaysia’s Contemporary Political and Economic Relations with Iran, International Relations and Diplomacy, 3(2): 122-133

Iran Ministry of Foreign Affairs (2019) Iran Ready to Cement Ties with Malaysia, October 25 2019 [Online] http://president.ir/en/111993 (Accessed 23rd February 2020)

Izzuddin, M., (2020) Malaysia wades into tricky waters with Kuala Lumpur Summit, Channel News Asia, January 02 2020, [Online] https://www.channelnewsasia.com/news/commentary/malaysia-kuala-lumpur-summit-islamic-muslim-politics-12222084 (Accessed 23rd February 2020)

Kamal, A. M. B., and Hossain, I., (2016) The Iranian diaspora in Malaysia: a socio-economic and political analysis, Diaspora Studies, 10(1): 116-129

Kaur, S. (2013). Qatar holding plans to invest in Pengerang. News Straits Times. [Online] http://www.btimes.com.my/articles/20130129234532/ (Accessed 23rd February 2020)

Kumar, P. P., (2019) Malaysia and Indonesia to take EU palm oil ban to WTO, Nikkei Asian Review, November 19 2019 [Online] https://asia.nikkei.com/Economy/Trade/Malaysia-and-Indonesia-to-take-EU-palm-oil-ban-to-WTO (Accessed 23rd February 2020)

Lali, G. P., (2020) Duterte to discuss US-Iran conflict with AFP officials, Global Inquirer, January 05 2020 [Online] https://globalnation.inquirer.net/182889/duterte-to-discuss-us-iran-conflict-with-afp-officials#ixzz6EJRpgkpM (Accessed 23rd February 2020)

Leverett, F., & Bader, J., (2010) Managing China‐U.S. energy competition in the Middle East, The Washington Quarterly, 29(1): 187-201

Liu, J. and Wu, L., (2018) Key Issues in China-Iran Relations, Journal of Middle Eastern and Islamic Studies (in Asia) 4(1): 40-57

Malik, A., & Edwards, S., (2018a) Saudi Arabia’s influence in Southeast Asia – too embedded to be disrupted? The Conversation, November 9 2018 [Online] https://theconversation.com/saudi-arabias-influence-in-southeast-asia-too-embedded-to-be-disrupted-106543 (Accessed 23rd February 2020)

Malik, A., & Edwards, S., (2018b) From 212 to 812: Copy and Paste Populism in Indonesia and Malaysia? The Diplomat, December 18 2018, [Online] https://thediplomat.com/2018/12/from-212-to-812-copy-and-paste-populism-in-indonesia-and-malaysia/ (Accessed 23rd February 2020)

Nair, S., (1997) Islam in Malaysian Foreign Policy (Routledge: Oxon)

Nyman, J., (2018) The Energy Security Paradox Rethinking Energy (In)security in the United States and China (Oxford University Press: Oxford)

The Energy Security Paradox: Rethinking Energy (In)security in the United States and China

Ooi, C. T., (2017) Malaysia Exporting More Palm Oil to Iran: Mah, New Straits Times, July 11 2017 [Online] https://www.nst.com.my/business/2017/07/256526/malaysia-exporting-more-palm-oil-iran-mah (Accessed 23rd February 2020)

Osman, M. N. M., (2016) The Islamic conservative turn in Malaysia: Impact and future trajectories, Contemporary Islam, 11(1)

Panda, A., (2020) After US Strike on Soleimani, China and Russia Coordinate at UN, The Diplomat, January 08 2020 [Online] https://thediplomat.com/2020/01/after-us-strike-on-soleimani-china-and-russia-coordinate-at-un/ (Accessed 23rd February 2020)

Patey, L., (2006) Iran and the New Geopolitics of Oil. DIIS Working Paper

Philippines Department of Foreign Affairs (2016) PHILIPPINES AND IRAN SUCCESSFULLY CONCLUDE THE SIXTH JOINT CONSULAR CONSULTATION MEETING, 09 February 2016, [Online] https://dfa.gov.ph/dfa-news/dfa-releasesupdate/8495-philippines-and-iran-successfully-conclude-the-sixth-joint-consular-consultation-meeting (Accessed 23rd February 2020)

Ravi, M., (2019) A Comparative Study of Iran and Saudi Arabia’s Foreign Policy Objectives in Indonesia, The Journal of Iranian Studies, 121-147

Razak, R. A., (2017) Escape from Isolation: Iran-Malaysia Relations during the Mahathir Years 1981-2003, paper presented at BRISMES Conference, University of Edinburgh

Shanahan, R., (2014) Malaysia and its Shi’a “Problem”, Middle East Institute, [Online] https://www.mei.edu/publications/malaysia-and-its-shia-problem Accessed 23rd February 2020

Shariatinia, M., (2011) Iran-China Relations: An Overview of Critical Factors, Iranian Review of Foreign Affairs 1(4). 57-85

Shariatinia, M., & Azizi, H., (2019) Iran and the Belt and Road Initiative: Amid Hope and Fear, Journal of Contemporary China, 28(120): 984-994

Sedgley, Z. (2012). Tension in the Asia-Pacific: Iranian-Malaysian relations and the West. RUSI 32(5) [Online] https://rusi.org/publication/tension-asia-pacific-iranian-malaysian-relations-and-west (Accessed 23rd February 2020)

Sipalan, J., (2020) Muslims should unite after Iran commander's killing: Malaysian PM, Reuters, January 7 2020 [Online] https://www.reuters.com/article/us-iraq-security-malaysia/muslims-should-unite-after-iran-commanders-killing-malaysian-pm-idUSKBN1Z60HX (Accessed 23rd February 2020)

Soltaninejad, M., (2017) Iran And Southeast Asia: An Analysis Of Iran's Policy Of "Look To The East", International Journal of Asia Pacific Studies, 13(1): 29-49

Sulong, Z. (2014). As anti-Shia campaign hits the pocket, minister seeks PAS’s help to restore Iran ties. The Malaysian Insider. March 3 2014 [Online] http://www.themalaysianinsider.com/malaysia/article/as-anti-shia-campaign-hits-thepocket-minister-seeks-pas-help-to-restore-ir (Accessed 23rd February 2020)

Sukma, R., (2003) Islam in Indonesian Foreign Policy (Routledge: Oxon)

Swaine, M. D., (2010) Beijing's Tightrope Walk on Iran, China Leadership Monitor, [Online] https://carnegieendowment.org/2010/06/28/beijing-s-tightrope-walk-on-iran-pub-41080 (Accessed 23rd February 2020)

Tehran Times (2016) Malaysia Interested in Boosting Ties with Iran: Veleyati, Tehran Times, July 22nd 2016 [Online] https://www.tehrantimes.com/news/404525/Malaysia-interested-in-boosting-ties-with-Iran-Velayati (Accessed 23rd February 2020)

The Philippine Star (2018) Expanding Philippines-Iran ties, The Philippine Star, March 04 2018, [Online] https://www.philstar.com/lifestyle/allure/2018/03/04/1793181/expanding-philippines-iran-ties (Accessed 23rd February 2020)

The Star (2017) King Salman's visit marks new era in Malaysia-Saudi Arabia relations, The Star, February 27 2017 [Online] https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2017/02/27/king-salman-visit-marks-new-era-in-malaysia-saudi-relations/ (Accessed 23rd February 2020)

The Star (2018) Najib on working visit to Saudi Arabia, The Star, January 08 2018 [Online] https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2018/01/08/najib-on-working-visit-to-saudi-arabia/ (Accessed 23 February 2020)

The Star (2019) Malaysia 'bullied' into closing Iranian bank accounts, says Dr M, The Star, October 30 2019 [Online] https://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2019/10/30/malaysia-039bullied039-into-closing-iranian-bank-accounts-says-dr-m (Accessed 23rd February 2020)

Utama, M. R., (2020) The US-Iran conflict and what it means for Indonesia, The Conversation, January 21 2020 [Online] https://theconversation.com/the-us-iran-conflict-and-what-it-means-for-indonesia-129621 (Accessed 23rd February 2020)

Van Bruinessen, M., (2013) Contemporary Developments in Indonesian Islam and the ‘Conservative Turn’ of the Early Twenty-first Century, in: van Bruinessen, M. (Ed.) Contemporary Developments in Indonesian Islam: Explaining the Conservative Turn (ISEAS: Singapore)

Vanaki, F., (2017) Iran, Thailand ties ‘unbelievable’, Iran Daily, March 11 2017 [Online] http://www.iran-daily.com/News/189158.html (Accessed 23rd February 2020)

Wain, B., (2009) Malaysian Maverick: Mahathir Mohamad in Turbulent Times (Palgrave: Basingstoke)

Yusof, I., (2007) The Southern Thailand Conflict and the Muslim World, Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs, 27(2): 319-339

I mention this example as I was present at a workshop hosted by ISIS with Veleyati as a speaker the following day, where I saw first-hand the warm response to the focus was on areas that Iran and Malaysia could deepen their ties, especially in response to extremism.