Northeastern Syria has witnessed profound political and military transformations since early January 2026, reshaping the balance of power in one of the country’s most strategically significant regions. These developments have raised serious questions about the future of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) and whether they can continue to exist as an autonomous military and political actor after nearly a decade of dominance east of the Euphrates.

The turning point came with armed confrontations in the neighbourhoods of Ashrafieh and Sheikh Maqsoud in Aleppo. While tensions between the Syrian state and the SDF had persisted for years, these clashes marked a decisive escalation. What initially appeared as localised fighting quickly evolved into a broader collapse of SDF control, triggering rapid territorial changes across northeastern Syria.

The clashes were closely linked to political disagreements over the implementation of a previous agreement between Damascus and SDF commander Mazloum Abdi, signed in March 2025. That agreement outlined the gradual integration of SDF forces into Syrian state institutions. However, factions within the SDF leadership, particularly those aligned with the Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK), viewed the deal as a threat to their autonomy and influence. By escalating tensions in Aleppo, these factions appeared to seek leverage against Damascus, hoping to renegotiate terms or attract renewed international attention.

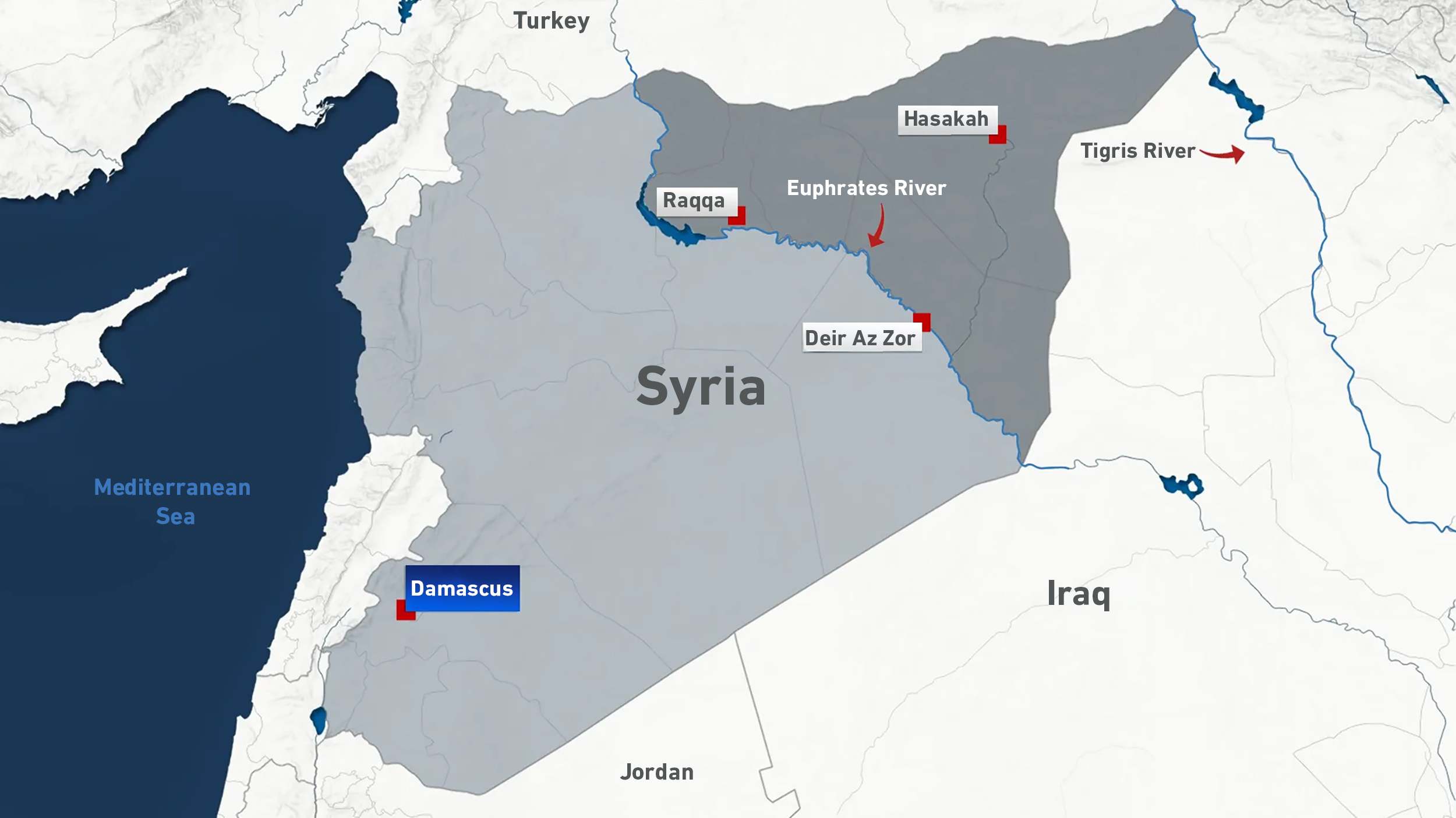

However, the strategy backfired. Within days, SDF forces withdrew from Aleppo entirely, and Syrian army units advanced swiftly into surrounding rural areas. This momentum soon extended eastward, allowing government forces to regain control over Raqqa and Deir Az Zor – regions that had been under SDF authority since the defeat of the Islamic State. The speed of the advance revealed the fragility of the SDF’s military posture once direct confrontation with the Syrian state resumed.

A decisive factor in this collapse was the position of Arab tribal fighters who had long constituted a significant portion of the SDF’s manpower. As government forces advanced, many of these fighters defected, abandoned their posts, or openly aligned with Damascus. These defections exposed the SDF’s limited social cohesion and undermined its claim to represent a broad, multiethnic coalition. In practice, loyalty to the SDF proved contingent on external backing and local calculations rather than deep political commitment.

Facing mounting losses, Mazloum Abdi signed a new agreement with Syrian President Ahmed al-Sharaa on 18 January 2026. The agreement, officially framed as a ceasefire and a roadmap for restoring state authority, acknowledged the return of Syrian government control over major territories previously administered by the SDF. While the deal temporarily halted large-scale fighting, its implementation remained uneven. In parts of the Jazira region, including areas around Hasakah and Kobane, SDF units resisted withdrawal, creating security vacuums and sporadic unrest.

The situation was further complicated by controversial actions taken by retreating SDF forces, including the release of hundreds of Islamic State detainees from Shaddadi prison without coordination with Damascus. This move drew widespread criticism and reinforced concerns that the SDF was willing to leverage security risks to maintain bargaining power, even at the expense of regional stability.

The roots of the SDF’s current predicament lie in its formation and evolution. Established in 2015 with strong US backing, the SDF emerged as a coalition dominated by the Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG) and closely linked to the Democratic Union Party (PYD). Although Arab groups were incorporated, leadership and decision-making remained overwhelmingly Kurdish. These structural imbalances limited the organisation’s domestic legitimacy and made it vulnerable once external support weakened.

For years, US military and political backing enabled the SDF to sustain de facto autonomy through the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria. However, this reliance also proved to be a strategic liability. As international priorities shifted and diplomatic channels between Damascus, regional actors and global powers evolved, the SDF found itself increasingly isolated. Without strong external guarantees, it lacked the leverage needed to preserve its autonomous status.

By mid-January 2026, the Syrian state had reasserted control over most key urban centres, infrastructure and resource-rich areas in northeastern Syria. While limited forms of local administration or security coordination may persist in some areas, the SDF’s ability to function as an independent armed force has been fundamentally undermined.

These developments signal not only the erosion of the SDF but also the likely end of the broader experiment in Kurdish-led autonomous governance in northeastern Syria. The region now appears set for reintegration into the Syrian state framework, marking a decisive shift toward re-centralisation after years of fragmentation.

*This is a summary of a policy brief originally written in Arabic available here.