|

| [AlJazeera] |

|

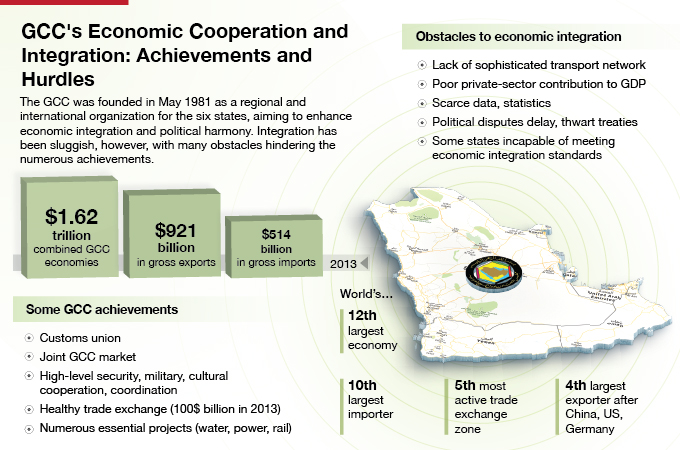

Abstract After the obstacles, the chapter examines the factors that motivate the GCC states to operate as an economic conglomerate rather than independently. Such factors include their geographic proximity, and shared customs and traditions. This chapter argues that their shared culture has given rise to similar legislative frameworks, thus facilitating the development of integrated regulatory frameworks, and enabling economic and financial integration. Despite this, the GCC’s progress towards integration has been relatively slow, even though the political and popular support for it has been reasonably strong. Deeper integration would undoubtedly contribute to member states achieving the aims and aspirations outlined in the GCC Charter, enhancing economic prosperity and benefitting both the larger and less influential member states. One way of furthering this agenda, and of establishing the distinction between the GCC’s political and economic goals, would be to distribute the offices of the GCC’s institutions more widely across the member states. |

Introduction

The GCC was established in May 1981 as a regional bloc including six member states – Bahrain, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates (UAE). Besides their geographical proximity, several factors facilitated the formation of the GCC, including shared customs, traditions and language, similar economic resources and activities, similar environments, and similar political systems (monarchies). The GCC aims to achieve comprehensive integration among its member states, with the ultimate goal being union. Article 4 of the GCC Charter states that the GCC aims to achieve coordination, integration and interconnection among member states’ economic, social, educational, research, cultural, legislative, and transport fields, and to develop compatible systems so that unity can be achieved.(1)

Through the GCC, the member states aim to form an effective economic bloc. Economic blocs elsewhere in the world have been formed by bringing different economies together under a single framework or set of principles governing how they deal with one another and with other countries. Member countries tend to choose their own level of participation within the bloc, ranging from partial integration to full union.

Integration usually begins with free-trade zones in which goods and services are exempt from customs and tariffs. If this is successful, a customs union is established, whereby participant states establish a common policy on international trade tariffs. The third level would be a joint market, where the means of production – including labour and capital – are able to move freely between member countries. After this comes the fourth level, where full cooperation in all economic, financial and fiscal policies occurs, and in which institutions, legislation and economic standards are set up for the next level – a common currency, which crowns the efforts of the member countries.

Economic blocs tend be set up between countries that have varied economic capabilities. For example, signatories to NAFTA (the North American Free Trade Agreement) have varying production costs, with the agreement enabling manufacturing companies to migrate from higher-cost to lower-cost regions, thus benefitting from cheap labour and production resources where these are more abundant.

As for the GCC, the factors that make integration a preferable option far outweigh those that might encourage the member states to remain independent. Geographical proximity is a major factor: the member states’ resources are close enough to channel into their industries, and their similar customs and traditions have produced similar legislative and administrative processes.

Despite the fact that their economic similarities centre on the production and export of oil, most of the GCC’s oil production is exported. Thus, competition between the member states for global oil sales is negligible. It should be pointed out that, via agreements on energy cooperation, the member states have given one another priority in relation to supplying their own energy needs. Thus all six states exchange crude oil, natural gas and petrochemicals in order to fulfil their respective local demands.

It doesn’t hurt that the economies of the GCC states have similar industries that might otherwise lead to competition between member states, with these similarities enhanced by the economic openness, especially given free trade agreements between them. An open economy promotes competitiveness, efficiency, innovation and, in some cases, convergence, making consumers the ultimate winners because competition keeps prices down and products diverse.

This chapter assesses the GCC’s progress towards complete economic union, which forms a key aspect of the GCC Charter, and covers both the GCC’s achievements in this area and the obstacles that have slowed it down.

Towards full economic integration

Economic unity makes the GCC an economic force to be reckoned with. As shown in the tables at the end of this chapter, in 2013, with an aggregate GDP of $1.62 trillion, the combined economy of the GCC states was ranked twelfth in the world in terms of size.(2) In terms of foreign trade in 2013, the GCC economy was rated fifth in the world, with US $1.42 trillion worth of trade exchange.(3) At US $921 billion in 2013, the GCC was the world’s fourth largest exporting nation after China, the US and Germany, with most of its exports consisting of crude oil, gas, and petrochemical derivatives. In terms of import value, the GCC came tenth globally at $514 billion in 2013. These figures indicate how much bargaining power the GCC has in the global economic arena, and how attractive the region is to foreign investment.(4)

The GCC’s ambitious economic integration project dates back to the very beginnings of the organisation. In November 1981, the GCC leaders signed an agreement on economic unity in Riyadh, laying out a comprehensive framework and timeframe for economic integration.(5) Among the many aspects covered by the agreement were: regulating capital flows; the cross-border movement of individuals; cooperation around issues of transport, trade, technology and development, as well as financial and fiscal cooperation.

In December 2001, the GCC leaders ratified an updated version of this agreement at their summit in Muscat. The updated document included articles that were more in keeping with national and international economic trends, facilitating the formation of the GCC’s customs union, a joint GCC market, and the yet-to-be-instituted common currency. The 2001 agreement thus constituted a vital advance in the GCC’s progress towards full economic integration.(6)

By March 1983, work had commenced on establishing a free-trade zone, one of the elements of a customs union. It was decided that local products and services would become fully tax and tariff exempt within the GCC, while each of the six states would maintain its own customs policies towards the rest of the world. After the updated agreement was ratified in 2001, the member states agreed to launch their customs union by January 2003, and to establish the accompanying databases and interconnectivity, so that they could keep track of the movement of goods and services, as well as of the GCC’s affairs in general.

In addition to the exemption of local products and services, a unified customs tariff of 5 per cent was made mandatory on all imports into the GCC. It was agreed that goods produced by member countries would not be subject to transit regulations when passing through other GCC nations, while non-GCC goods in-transit, would be treated as such only at the first entry point with no need to repeat procedures at subsequent inter-GCC crossing points. The agreement also freed GCC citizens from requiring customs clearance when moving between any of the six states. It was also agreed that the standards and measures related to trading in goods in each country would be considered mutually acceptable until a single set of common standards and measures could be put in place.

By the end of 2008, the GCC states had successfully established a customs union with streamlined procedures, customs legislation, and standards. In the same year, the member states agreed to move to the next level by establishing a joint market. This would require not only the elimination of all customs restrictions on the movement of goods between the six states, but also the removal of restrictions on the movement of capital and individuals. This meant that all GCC citizens would be allowed to own property and do business in any of the six states, while being treated like any other natural-born citizen of these states.

With this accomplished, the next step is monetary union through the adoption of a common currency, an objective that the GCC’s supreme council had been discussing since 2000. In 2001, the member states agreed on a timeframe that included pegging their currencies to the US dollar, and aiming to launch their common currency in 2010. By 2002, the local currencies of all six member states had been officially pegged to the US dollar.

Taking a leaf out of the European Union’s book, the GCC states laid down several economic standards required for economic integration under a common currency. The standards underline the need for every state to maintain key economic indicators at or above certain levels, and stipulate (among other things) that:

• National debt should not exceed 60 per cent of a given state’s GDP.

• The national budget deficit should not exceed 3 per cent of a state’s GDP.

• National inflation should not exceed 1.5 per cent of the average inflation of all member states combined.

• Long-term interest rates should not exceed 2 per cent of the average interest rates of all the GCC member states combined.

In 2005, the GCC agreed to establish a fiscal council that would later become a GCC central bank. However, things got a little more difficult after 2005, when a series of events dampened enthusiasm for a common currency. In 2007, citing the considerable fluctuations in the value of the US dollar as problematic, Kuwait rescinded the pegging of its currency to the dollar, and chose instead to peg it to a currency basket, while pointing out that this included an option for them to peg their currency against the dollar again in future if they chose to do so. In January 2007, Oman declared that its economy was unable to achieve the requirements for a common currency, and unilaterally announced that it would postpone joining the common currency, leaving other, more ready member states to proceed. The strongest blow to the common-currency project came in 2009 when the UAE decided to withdraw from the project entirely when its request to host the headquarters of the GCC central bank in Abu Dhabi (instead of in Riyadh as had been planned) was declined.

By early 2010, the common-currency debate was still in full swing. The GCC’s fiscal board held its first meeting in Riyadh in March 2010, during which the board members agreed to postpone the launch of the common currency until 2015. This marked the beginning of a critical phase for assessment of the preparedness of the four countries which remained committed to the project to adopt and communise a common currency. In addition, it was agreed that Oman’s readiness to rejoin the project would be studied, as would the issues arising from the UAE’s demand to host the GCC central bank. Recommendations are due to be made based upon the results of these assessments at some point in 2015, after which a decision will be made about whether to launch the currency this year or postpone it to a later date.

Progress towards economic integration: achievements and hurdles

There is no questioning the fact that the establishment of the customs union and the joint market, as well as the accomplishments to date towards introducing a common currency, are achievements in and of themselves. That said, there is no denying that more than three long, hard decades later, this rather elusive economic bloc has yet to fully materialise. This may seem strange given that the economies of the GCC were probably better suited to fast-tracking an economic union than the European Union, which crowned its 42-year gestation period by issuing the euro in 1999. (Initially known as the European Economic Community, the EU has always had more, as well as more vastly dissimilar, members than the GCC. When the euro was first issued, eleven European countries chose to adopt it as their national currency. By 2015, that number had grown to eighteen.)

This section will outline what has been accomplished in the interests of economic cooperation between the GCC states on a number of important fronts.

Common trade activities

Perhaps the GCC’s greatest achievement to date has been its success in invigorating trade among its member states, via the customs union and the joint market. Merely getting this far was sure to have a positive impact on mutual trade. As shown in the tables at the end of the chapter, almost $100 billion in trade took place between member states in 2013. This is seven times greater than it was in 2000, before the launch of the customs union. Despite this dramatic growth, however, mutual trade still represents a mere 7.1 per cent of the aggregate foreign trade conducted by the six member states.(7)

There are some very good reasons why mutual trade between member states has not grown further to date. One challenging factor is that although the customs union is now long established, mutual trade is still hindered by lengthy, time-consuming customs procedures at border entry points, especially at land-based border crossings.

An essential element in the growth of mutual trade is a well-developed, transport network capable of facilitating the rapid and efficient movement of goods and cargo between states. A good transport network would include roads, seaports, airports and railways. Unfortunately, the road infrastructure across the GCC is still weak, poorly maintained and poorly serviced. Some road projects connecting GCC countries which should already be fully operational remain stuck at the stage of feasibility studies or designs that have yet to be completed. In addition, an inter-state railway project, ratified by the GCC’s supreme council in 2003, which was supposed to be up and running by 2018, has yet to see the light of day. A good transportation network would go a long way towards cutting transport costs and contributing to the stability and balance of the GCC’s common market.

In 2007, the region’s construction industry experienced some pricing anomalies that were made more serious by shortages of key materials such as concrete, cinder blocks and construction steel. An effective transport network (be it a railway or an advanced highway network) would have allowed companies to transfer materials from manufacturers to those locations where the shortages were most severe, thus helping to meet local demand and protect against inflation.

By contrast, some truly commendable strides have been made in air transport, with the GCC having one of the world’s most active aviation networks. Thanks to its advantageous geographical position between East and West, the GCC states have become a refuelling hub for many of the world’s airlines.

The GCC countries have also agreed to increase the number of flights between their capitals and major cities, allowing their national carriers to sell tickets directly in all GCC states, without the need for local agents or sponsors. These measures have helped to boost the movement of people, baggage and other cargo, bolstering business, as well as strengthening family ties, travel and tourism. Dynamic aviation activity has also led to an increase in the number of airports and justified the expansion of existing ones.

The role of the private sector

Despite hopes that the private sector would be an engine of commercial and investment exchange within the GCC, its contribution to the GDP of the six member states still falls far short of the levels hoped for. The private sector’s capabilities in relation to innovation, especially in terms of producing globally competitive brands, institutions or services, are considered meagre at best. While some goods produced by the private sector, such as dairy and other agricultural products, have been remarkably successful, internal weaknesses combined with poor transport and other infrastructure, have prevented private sector firms from contributing more to economic activity and mutual trade between member states.

Additionally, the disproportionately large role played by the government sector in GCC member states’ economies has attracted far too many citizens, giving them incomes that compete with, or even exceed, what they would be likely to earn in private businesses or as entrepreneurs. This has been going on for far too long, creating a situation in which much of the private sector consists of small and medium-sized businesses that are run and managed by foreigners, and whose activities focus on importing goods and services that are too poor in quality to compete globally. These enterprises rarely display even a modicum of innovation, partly because of limited capital, and partly because of their total reliance on imports for retail sales.

On this issue, the GCC has focused mainly on eliminating obstacles that hamper private sector growth in member states. For instance, the GCC set 2003 as the year in which all obstacles preventing GCC citizens from owning stock and establishing enterprises in any GCC state would be removed. Nevertheless, few businesses enter into partnerships or establish branches in other GCC states. Most business partnerships are still confined to capital investments and channelled towards stock market investments, with a dearth of partnerships, alliances and affiliations aimed at forming industrial conglomerates that could compete regionally and globally.

Although several initiatives to jumpstart business leadership in member states have been established, the GCC has yet to adopt a GCC-wide business-leadership programme. However, in November 2014, a business-leadership council was established in Riyadh, and much is expected from this.

The integration of financial markets

The GCC’s economic agreements encourage the integration of financial markets and the standardisation of the policies, laws and regulations governing them. Each member state has its own official primary and secondary financial markets (stock exchanges) that deal in financial instruments such as stocks, bonds, investment and hedge funds. The GCC’s general secretariat, and the regulatory bodies linked to the financial markets in each of the member states, are engaged in ongoing discussions about standardising the regulations governing stock and bond offerings, investment funds and levels of disclosure, as well as about legalising reciprocal stock offerings between GCC states.

A committee comprising the heads of capital-market authorities from each of the member states has drafted a set of standardised rules and regulations to assess how well these fit with the capital markets in their respective countries, which could be used until a fully integrated system is in place. This committee is also working with the governors of the member states’ central banks to find ways to bolster regulatory and monitoring systems so as to guarantee the financial security and integrity of those markets. Work is also underway to maximise economic development by boosting the GCC states’ abilities to attract investment and create opportunities for investors in various enterprises.

That said, progress has been slow. IPO markets – in which initial public offerings (IPOs) are used to raise funds for emerging and existing enterprises – are still very loosely interconnected. Although some GCC countries allow citizens of other member states to own IPO shares in their companies (such as Qatar’s Al Rayan Bank and the UAE’s Dana Gas), there is still very little opportunity for GCC citizens to own shares in out-of-state companies. The situation is no better in investment-fund markets. As for secondary-trading markets (stock exchanges), certain listed companies can be co-traded between certain GCC states; thus the stock exchanges of Dubai and Qatar can trade shares in companies such as telecommunications company Ooredoo or the Alsalam Aircraft Company. Additional freedom in such trading would almost certainly enhance economic integration and stimulate trade within the GCC.

Making progress in this direction, Qatar has given all GCC citizens the same rights as Qatari nationals to own shares in Qatari companies, thus giving GCC citizens an advantage over foreign investors. In addition, Qatar has raised the maximum percentage of shares that non-Qataris can own in Qatari enterprises from 25 to 49 per cent.

The GCC database

The quality and comprehensiveness of statistical data enhances the efforts of any state to standardise systems, practices, regulations and policies. Although the GCC’s general secretariat has a database that gathers, tallies, collates and documents all manner of economic, social, cultural, environmental and other data within the GCC, the availability of the more detailed longitudinal data could be improved. Researchers’ lack of access to such data tends to impact badly on the quality of studies conducted and/or published in the GCC, as well as on the identification and solving of problems, and the prediction of future trends. Far too often, researchers find themselves having to draw on data from external, international sources about their own countries. Statistics-collection bodies in each of the six member states’ would benefit from more attention and investment, and statistical standards should be reviewed and standardised – ideally all six states should adopt international standards, making it easier for analysts to compare data and track specific variables in relation to global trends.

Political will

It can hardly be said that the GCC leaders lack the political will to achieve economic and political unity. The GCC would not have come about in the first place, much less continued to function, if the political will did not exist. Throughout the history of the GCC, no member state has ever barred the flow of goods and services, or restricted the movement of individuals from other member states, despite the occurrence of several political disagreements between states – including territorial disputes or issues relating to the foreign policies of one or other state. Nevertheless, it must be acknowledged that such disputes have played a role in delaying or obstructing certain GCC agreements.

To eliminate such political and economic loopholes, increased coordination between the member states is necessary. For instance, benefits and wealth should be distributed among member states in a way that is fair to the countries that have more economic clout, while increasing the benefits for those countries with less economic power. For example, the premises and headquarters of GCC institutions could be distributed across the member states and each member state could be accorded importance based on whatever the country excels in. For instance, Bahrain has financial status, the UAE has tourism and exports, Saudi Arabia has oil, Qatar has gas, Oman has its breath-taking wilderness and an edge in terms of labour resources, and Kuwait has the most experience in relation to global investments.

The GCC is perfectly capable of preventing political dynamics from undermining what it has achieved so far in terms of economic integration. For example, the recalling of ambassadors from Qatar in 2014 could have been an unprecedented setback for the GCC and its economic achievements but, in time, the GCC proved its ability to resolve internal differences in ways that have no impact whatsoever on the member states’ economic affairs. The return of the various ambassadors to Doha was a political success that proved that the GCC is more than capable of containing and satisfactorily resolving even serious disputes.

Conclusion

The GCC was born in the early 1980s, but it can be argued that it only commenced its work in earnest in 2001, when the member states began to focus on achieving economic integration through forming a customs union and a joint market. Efforts are still underway to achieve the ultimate goal, a common GCC currency, and progress towards integration has been relatively slow. Nevertheless, the political and popular will to press on remains strong, and although some hurdles remain, a great deal has already been achieved towards meeting the hopes and aspirations of GCC nations, as expressed in the GCC Charter.

Tables

|

Economic Size (Millions of Dollars, 2013) |

||

|

1 |

United States |

$16,800,000 |

|

2 |

China |

9,240,270 |

|

3 |

Japan |

4,901,530 |

|

4 |

Germany |

3,634,820 |

|

5 |

France |

2,734,950 |

|

6 |

United Kingdom |

2,522,260 |

|

7 |

Brazil |

2,245,670 |

|

8 |

Russia |

2,096,780 |

|

9 |

Italy |

2,071,310 |

|

10 |

India |

1,876,800 |

|

11 |

Canada |

1,825,100 |

|

12 |

GCC |

1,628,000 |

|

13 |

Australia |

1,560,600 |

|

14 |

Spain |

1,358,260 |

|

15 |

South Korea |

1,304,550 |

|

16 |

Mexico |

1,260,920 |

|

17 |

Indonesia |

868,350 |

|

18 |

Turkey |

820,210 |

|

All tables compiled by the author, using data obtained through a Bloomberg LP subscription. |

||

|

Top Economic Trade (Millions of Dollars, 2013) |

||

|

1 |

China |

$4,228,910 |

|

2 |

United States |

3,763,610 |

|

3 |

Germany |

2,597,240 |

|

4 |

Japan |

1,618,520 |

|

5 |

GCC |

1,420,000 |

|

6 |

France |

1,259,888 |

|

7 |

Netherlands |

1,203,662 |

|

8 |

South Korea |

1,105,408 |

|

9 |

United Kingdom |

1,090,339 |

|

10 |

Canada |

966,823 |

|

All tables compiled by the author, using data obtained through a Bloomberg LP subscription. |

||

|

Top Exporters (Millions of Dollars, 2013) |

||

|

1 |

China |

$2,282,060 |

|

2 |

United States |

1,495,290 |

|

3 |

Germany |

1,423,020 |

|

4 |

GCC |

921,000 |

|

5 |

Japan |

786,177 |

|

6 |

Netherlands |

617,698 |

|

7 |

France |

595,049 |

|

8 |

South Korea |

589,823 |

|

9 |

Russia |

521,649 |

|

10 |

Italy |

509,951 |

|

All tables compiled by the author, using data obtained through a Bloomberg LP subscription. |

||

|

Top Importers (Millions of Dollars, 2013) |

||

|

1 |

United States |

$2,268,320 |

|

2 |

China |

1,946,850 |

|

3 |

Germany |

1,174,220 |

|

4 |

Japan |

832,343 |

|

5 |

France |

664,839 |

|

6 |

United Kingdom |

622,034 |

|

7 |

Netherlands |

585,964 |

|

8 |

Hong Kong |

524,108 |

|

9 |

South Korea |

515,585 |

|

10 |

GCC |

514,400 |

|

All tables compiled by the author, using data obtained through a Bloomberg LP subscription. |

||

|

GCC Intra-Regional Trade (Millions of Dollars, 2013) |

||||||

|

Qatar |

Saudi |

UAE |

Oman |

Kuwait |

Bahrain |

|

|

Qatar |

2454.39 |

8381.36 |

1570.68 |

1481.28 |

456.4 |

|

|

Saudi |

2454.39 |

8141.18 |

4623.43 |

2629.5 |

5050.85 |

|

|

UAE |

8381.36 |

8141.18 |

15689.37 |

1692.18 |

1267.04 |

|

|

Oman |

1570.68 |

4623.43 |

15689.37 |

777.67 |

385.55 |

|

|

Kuwait |

1481.28 |

2629.5 |

1692.18 |

777.67 |

279.16 |

|

|

Bahrain |

456.4 |

5050.85 |

1267.04 |

385.55 |

279.16 |

|

|

Total |

$14,344.11 |

$20,444.96 |

$26,789.77 |

$21,476.02 |

$5,378.51 |

$6,982.60 |

|

Total (ALL) |

$95,415.97 |

|||||

|

All tables compiled by the author, using data obtained through a Bloomberg LP subscription |

||||||

|

GCC Intra-Regional Trade (Millions of Dollars, 2000) |

||||||

|

Qatar |

Saudi |

UAE |

Oman |

Kuwait |

Bahrain |

|

|

Qatar |

276.32 |

320.54 |

24.35 |

27.76 |

58.77 |

|

|

Saudi |

276.32 |

1508.95 |

242.3 |

719.13 |

1268.09 |

|

|

UAE |

320.54 |

1508.95 |

1487.86 |

397.76 |

243.66 |

|

|

Oman |

24.35 |

242.3 |

1487.86 |

50.48 |

40.28 |

|

|

Kuwait |

27.76 |

719.13 |

397.76 |

50.48 |

80.25 |

|

|

Bahrain |

58.77 |

1268.09 |

243.66 |

40.28 |

80.25 |

|

|

Total |

$707.74 |

$3,738.47 |

$3,638.23 |

$1,820.92 |

$1,247.62 |

$1,632.28 |

|

Total (ALL) |

$12,785.26 |

|||||

|

All tables compiled by the author, using data obtained through a Bloomberg LP subscription |

||||||

________________________________________________________

* Dr Khalid Shams Abdulqader is a professor at the College of Business and Economics, Qatar University

1. The GCC Charter is available at http://www.gcc-sg.org/eng/indexfc7a.html

2. All tables in this chapter were compiled by the author, using data obtained through a Bloomberg LP subscription; see http://www.bloomberg.com/company.

3. The numbers in this segment were all compiled using data obtained by the author through a Bloomberg LP subscription.

4. Ibid.

5. The 1981 agreement is available at http://www.gcc-sg.org/index95fb.html?action=Sec-Show&ID=395 and in English at http://www.gcc-sg.org/indexbbe3.html?action=Sec-Show&ID=53.

6. The 1981 Economic Agreement is available at http://sites.gcc-sg.org/DLibrary/download.php?B=168.

7. Ibid.