|

| [AlJazeera] |

|

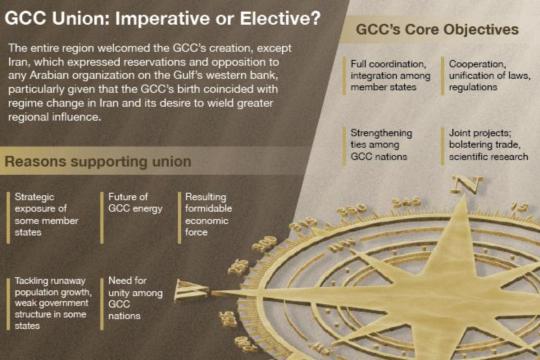

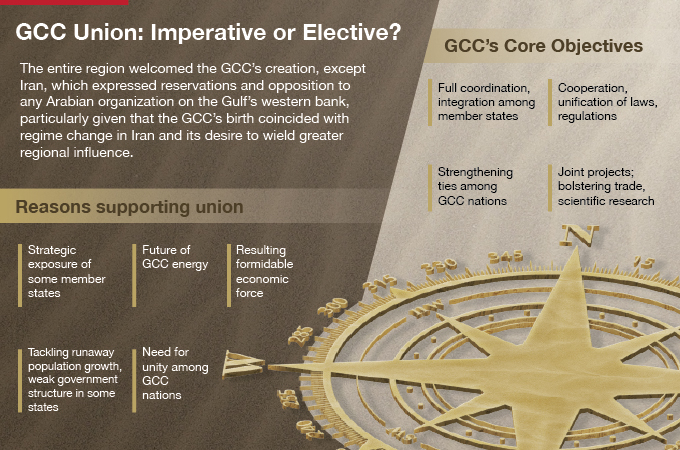

Abstract Given this reality, and the fact that the member states now face challenges that are a far cry, both in nature and in magnitude, from those that brought about the GCC’s creation in 1981, this chapter suggests that a stronger union among the six states has become a necessity rather than a choice. Such unity would create a robust entity more capable of handling challenges and threats than the six states are able to manage alone. Ultimately, a stronger union would also strengthen and augment pan-Arab unity. In this context, this chapter outlines a number of factors that help to justify support for such a union. These include the strategic, political and economic vulnerabilities of certain member states, wayward population growth, the challenges facing the energy industry, and the advantages of enhancing a sense of unity among the citizens of the various states. |

Introduction

In December 2011, King Abdullah bin Abdulaziz of Saudi Arabia proposed that all six GCC member states form a union. Inspired by the ideas of philosopher Ibn Khaldun, who proposed that prosperity is both economic and social, and that sound political and educational systems are the ultimate expressions of prosperity, the proposal drew on notions of identity and nationhood, emphasising that the Gulf states are an integral part of the Arab and Muslim world.

When the GCC was established on 25 May 1981, its first memorandum highlighted the special ties between the six nations, as well as the similarities in their forms of governance, their political and social institutions, their shared heritage and their cultural connections. With the exception of Iran, which was quick to express its doubts and reservations and objected to the idea of an Arab organisation on the west coast of the Arabian Gulf, the birth of the GCC was welcomed across the region.

In its quest to achieve this influence, one of the first steps taken by the GCC was to create a customs union. At its 23rd session, held in Qatar on 21 December 2002, the organisation announced that a customs union would come into effect on 1 January 2003. Procedures agreed to by the GCC’s Financial and Economic Cooperation Committee (consisting of the ministers of finance and economy for the six member states) were then approved.

In 1990 and 2003, the GCC overcame two severe challenges to its existence, although the first was perhaps less critical. Despite the varied ways in which they responded to the 1990 Gulf War, the GCC states were nevertheless unanimous in condemning it. In 2003, however, when the US invaded Iraq, the varied interests of the six member states, and strains caused by minor border disputes, as well as the deployment of the GCC’s joint military force (the Peninsula Shield), seemed to undermine the possibility of a real union coming to fruition.

Yet, despite these and other less serious troubles, the GCC remained intact. Continuing attempts to unify and integrate their respective systems in the quest for fuller coordination and integration seem set to enhance the developmental, economic, educational and administrative stability of member states and of the region more generally.

That said, the conditions into which the GCC was born were vastly different from those it faces today. Member states still face many developmental and economic challenges, and urgently need to diversify their economies so as to reduce their dependency on oil as their primary source of revenue.

According to the GCC’s website, 47 million people currently live in the GCC states as of 2014, and the combined gross national product (GNP) of the six member states amounts to US $1.6 trillion.(1) High population levels make it imperative for the Gulf states to diversify their economies, and to seek strategic political and economic alliances that can bolster their economic influence regionally and globally.

Why unity has become a necessity

A Gulf union would provide a more robust entity, capable of shouldering the burdens that individual states currently find themselves struggling to bear, and could ultimately strengthen pan-Arab unity. Points in favour of forming a union include:

• The strategic exposure of some member states.

• The future of the GCC’s energy industry.

• The consolidation of significant economic muscle.

• Opportunities for addressing population growth as well as the political and economic vulnerabilities of certain member states.

• The potential to foster a deeper sense of unity between the peoples of the six states.

Perhaps the strongest argument in favour of such a union is regional and international integration. Economic and political cooperation would help to create a community of interests between member states and reduce the likelihood of any member state resorting to violence to resolve a conflict with any other member. As for which form of union would be best, Turki al-Harbi has argued that a confederacy would preserve the respective sovereignty of each individual state while maintaining the vision for which the GCC was conceived?(2)

Given the pace of change in the region, the Gulf states have little option but to adopt a unified political stance if they wish to confidently meet the challenges they face. One possible way to achieve this would be for the ministries of petroleum, defence and foreign affairs to merge across all six states. Further integration and joint institutions could also be beneficial. For example, a GCC supreme court could be established, while on the issue of employment priority could be given to addressing unemployment in all member states by creating databases of graduates and unemployed citizens, thus ensuring a more efficient allocation of human resources across states. Such joint institutions and projects would strengthen the development, not only of current member states, but also of countries that might join the GCC in future.

Comprehensive security

Cooperation on security matters already enables the GCC states to better understand and address the real strategic concerns that affect the region. The security of GCC member states bolsters regional peace and social solidarity, giving all six states additional strategic and political traction regionally and internationally.

To understand how nations have traditionally secured and bolstered their security, it is useful to revisit the ideas of Thomas Hobbes and Emanuel Kant. Hobbes used the concept of a Leviathan to represent states that place the defence of their own interests at the apex of national priorities. Yet, many heads of state see themselves as rational actors who have the right to prioritise national interests (meaning national security), and to marginalise or eliminate all threats to their own sovereignty by maximising the power of the state, thus enforcing, rather than promoting, national security.

Emanuel Kant suggested that human populations can govern themselves according to moral and legal parameters, and introduced the concept of perpetual peace. According to the Dictionnaire de Stratégie (Dictionary of Strategy),(3) this concept ties security to the highest forms of social co-operation, namely: solidarity and a collective sense of belonging.

Of course, any notion of security can be manipulated or given double meanings so as to fit specific political, social, economic and legal ends. The concept is certainly subject to global variables, as well as to the inner workings of states and what they choose to define as acceptable means of achieving political ends. The real problem is that all facets of society can be painted with a “security brush” – in such conditions, rather than developing a universal and shared understanding of what security actually means and should be based upon, the notion of security tends to be usurped by the signature atmosphere of a security state. When almost everything can be classified as a ‘”security risk”, concerns relating to human rights tend to be quickly cast aside.

That said, it is important to note that the connection between national identity and security is crucial. A critical issue here is that the differences in the laws and liberties of each GCC state could give rise to problems and conflicts related to security issues. Alternatively, such differences might prompt some states to expand the liberties available to their citizens.

Identity and security in the Arabian Gulf

If it is accepted that identity is strongly connected to security, it is possible to investigate the nature of this connection by questioning what identity is, and how it relates to security. In the context of the GCC states, various questions are relevant. For example, what is the identity of GCC states? What does it mean to be a Khaleeji (Gulf Arab)? How can this identity and an understanding of it contribute to maintaining security and safeguarding national resources?

When the GCC states are considered as a geographical unit in which identity is solidly tied to security, we can begin to think about how linguistic security pertains to geographical unity, what sovereign security means in terms of culture, and about cultural unity in a pluralistic context. It can safely be said that identity and security are key components of the behavioural patterns of individuals and groups, and also of their relationships with their rulers. As such, any weakness in identity implies a weakness in a key aspect of security.

Weaknesses in identity manifest in what Marxists and existentialists call “alienation”. Although an accepted phenomenon in cognitive psychology, alienation is by no means a purely psychological or psychopathological phenomenon; it is an existential one: the soul exists in the body, and the body exists in the world. Forms of alienation abound: religious, social, cultural, and political alienation are just a few. Perhaps the most powerful of these is religious alienation: estrangement from God can make us feel liable to disappear into oblivion – as if all our ties with the world could be severed. Likewise, social insecurity or alienation from the societal structures or institutions that should help citizens to feel safe – the type of alienation of the most concern in this chapter – is a condition in which citizens feel so out of touch with normality that, at best, they feel unconcerned or unfazed by criminality, and, at worst, lose their connection with, and sense of belonging to, society. The latter often occurs when high levels of social insecurity are combined with social and political alienation or exclusion.

This raises a few questions about how political insecurity widens the rift between citizens and states. For example, does the rapid progress made by the six GCC member states since the GCC’s inception reflect the identity of Khaleeji citizens? Is there any parity between the rapidity of change and the speed with which Khaleeji citizens adapt to change? Does the timing of what Khaleeji citizens are witnessing in their societies belong to the period in which they feel they belong?

Frenemies: a stairway to unity?

The concept of the “frenemy”(4) in international politics is useful in understanding the complexities of relations within the GCC, as well as the GCC’s relations with other Arab countries and Iran. In the current context, the GCC states cannot consider having any absolute enemies. Instead, the GCC states must develop and evolve strategies that maintain their own national interests, and take into account the interests of other parties, so as to avoid all-out conflicts.

Reinforcing the GCC system: the concept of national sovereignty

As Dr. Abdullah al-Nufaisi pointed out in his suggestions regarding the enhancing of unity and harmony within the GCC institutions, the spectre of having to give up part of their authority haunts GCC member states. This is particularly true in relation to strategic decisions. Nevertheless, member states are still striving to harness the will, the capability and determination to achieve a union that enjoys power and influence, and is capable of making joint decisions on security, economics and foreign affairs.

The GCC member states still have a long way to go in terms of integrating their laws and regulations, not to mention building the kinds of “ultra-governmental principles” that could pave the way for agreement on a pan-GCC constitution. Concrete steps toward this will undoubtedly be motivated by the quest for prosperity, and the preservation of ruling bodies on the one hand, and, on the other hand, by security threats and the need to co-ordinate responses to those threats.

Inter-GCC interaction

The near-immutability that prevailed in the GCC states before 2010 was shattered by the phenomenon known as the Arab Spring. The speed and unpredictability of change in the Arab world has shaken the collective political mind-set of GCC leaders to the core, forcing a rethinking of concepts that had previously been taken for granted, such as sovereignty, borders, and statehood.

One of the most prominent results of the Arab Spring is shaky states: the profound changes that have occurred have given rise to jenga-like towers – entities that are liable to topple as quickly as they are propped up. Some pundits have suggested that such states might be failing rather than being born, and that their instability might pose a threat to regional nations. Citing chaos theory, these analysts argue that something as simple as birds flapping their wings in the Mediterranean could cause hurricanes in the Arabian Gulf, which is already beleaguered by numerous regional and internal threats.

In a paper titled “Saudi Arabia and Qatar in a time of Revolution”, Bernard Haykel, a professor at Princeton University and member of the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington DC, discusses the challenges facing Qatar and Saudi Arabia as follows:

“The Arab Spring represents a set of challenges, the likes of which have not been seen in the Arab world for a half-century or more. Shifts underway in the Levant and North Africa have a profound effect on perceptions of governance in the Gulf, and those shifts are a potential source of threat to the GCC states’ stability. In response, Qatar has been active, building on confidence in its domestic support and its conviction that it has nothing to fear from actors like the Muslim Brotherhood. Saudi Arabia has been considerably more cautious, reflecting its own diverse internal politics and the leadership’s distrust of sweeping change. Both Qatar and Saudi Arabia seek to use their wealth as an instrument of their foreign policy, shaping the external environment in order to secure their internal one. So far, they are succeeding”.(5)

On the other hand, tensions surround the Joint GCC Security Agreement,(6) which states that the security of member states is the collective responsibility of all. However, the extent to which this agreement can be activated, not only cooperatively at the internal and regional levels, but also as an instrument for pressure, is still to be determined. In attempting to address this issue, the next section outlines the constant and the variable factors that shape events in GCC countries, and present the case in favour of GCC unity, followed by an explanation of the principles that govern inter-GCC relations.

Constant factors

Geography is one of the most important constants in inter-GCC relations. Being a single geographical entity, the Arabian Peninsula can be neither physically torn apart nor hidden away on the geographical or political map of the Arab world. Inseparably tethered to the geographical factor is the fact that Khaleeji citizens share customs, traditions, ancestry, culture, language and religion. While various interpretations of religion have played a major role, shared Arabian human heritage is still powerful enough to override such differences.

Likewise, extended families are another significant constant. Relationships of kinship and marriage form a robust and extremely complex social web that spans the nations of the region. The Khaleeji nation is an inseparable component of the greater Arab nation, and thanks to the prevailing human factors, it enjoys ethnic homogeneity. This homogeneity cements the region’s geographical and religious unity, as well as its customs and traditions.

The common language is a major unifier in the region; a common language is a kind of glue that can literally spell the longevity or demise of nations and civilisations. What further solidifies the GCC community is a sense of shared perspectives and sentiments. This was particularly evident during the Iraqi occupation of Kuwait, when GCC nations adopted a common stance despite the undeniable impact this would have for the region both militarily and economically. All of these constants interact with, as well as react with, the variable factors outlined below.

Variable factors

With its political and military moves against GCC member states, and its relentless prevarication with its nuclear programme, Iran has to be seen as an ongoing threat. Iran’s determination to stake its claim in the region is a key motivation for its nuclear programme: Iran views its nuclear weapons capacity not only as a strategic deterrent, but also as a way of keeping up with the Joneses – in this case, India and Pakistan. On the other hand, some GCC countries are building relations with Iran, and despite the ongoing threat it poses, the issue of Iran has not been a major source of tension in the GCC.

In recent years, the world seems to have become a more dangerous place than ever before. Writing about failed and fragile states in The Responsibility to Protect: Ending Mass Atrocity Crimes Once and for All, Gareth Evans describes the types of problems that bring about such crises, and explains how states put themselves and neighbouring countries in danger by failing to resolve internal rifts. By their inability to act, such states export terrorism and extremism to their neighbours, and/or trigger a mass exodus of refugees.

The concept of security among GCC states is another important variable. As Iran gained the upper hand in military might at the expense of GCC states, indirectly aided by declining US involvement in the region, the US was rendered unable to militarily intervene in Syria, leaving that embattled country wide open to Iranian penetration and support for Bashar Assad’s regime. In response, the GCC states developed their own varying definitions of national and regional security. Although they agreed that security had become a top priority, the ways in which each state interprets this, in terms of determining and dealing with threats, are different – with their well-known differences concerning how best to respond to the Muslim Brotherhood being a case in point.

That said, Article 7 of the Joint GCC Security Agreement attempts to contain such differences of interpretation. The agreement states that ‘ministries of interior and similar security bodies in member states are to consult in advance, and their representatives shall coordinate and unify their stances on issues on the agendas of regional and international conferences and meetings.’ Nevertheless, the varied interpretations of national security that apply all over the world(7) are mirrored in the disparities between the foreign policies of the GCC states. For now, it can be argued that the security agreement has only a relatively loose influence on each state in terms of how they deal with security threats.

Fortunately, the proverbial political weight that the GCC countries hold collectively is not heavily compromised by these differences. Their political weight manifests itself in joint institutions which affect many aspects of the daily lives of Khaleeji citizens. Citizens have reaped the benefits of numerous joint programmes linked to culture, education and healthcare, as well as to the quest to achieve consistency across institutions and legislation. This has created a popular unity that goes even deeper into their culture, and is reflected in their songs and poetry. Another good example of this occurred in November 2014 when Qatar won the 22nd Gulf Cup of Nations in Riyadh, and the Saudis showed the utmost respect for their victory. Clearly, this league of nations had amassed massive amounts of solidarity over the years.

Challenges affecting GCC unity

The mismatch between the rapidity of change and the pace at which society adapts to change could potentially create a political, social and economic black hole in member states. Given the social resentment caused by the huge gaps between rich and poor, and the general sense of frustration across all social classes, the question is whether this could bring about some sort of revolution.

Certain strategic issues – such as the concept of citizenship, and whether or not this should be conditionally tied to ideological tendencies – pose challenges that impact on a number of GCC institutions, including its elected councils and constitution.

Popular movements and regional forces require multi-faceted (religious, cultural, economic, social, and political) interaction, and now that some Arab revolutions have turned from being peaceful into armed struggle, this could have a negative impact on the six GCC member states. Internal reforms within the GCC states pose a definite challenge. To address chronic, flaws and shortcomings in state institutions,(8) a lot of repair work is necessary. This, in turn requires political will, and a harnessing of elements that facilitate regional unity.

Economically, the challenge of resources – specifically energy resources – must be considered. GCC states possess some 500 billion barrels of confirmed oil reserves,(9) and oil plays a major role in the GCC states’ economic policies. Oil remains a strategic commodity for GCC countries, and the primary source of revenue for most of them. This will greatly impact the health of GCC economies and their quest for unification, especially if the benchmark price for Brent Crude continues to drop so dramatically.(10)

Failure or even slowness in responding to the rapid developments in countries surrounding the GCC states will leave the field wide open for the potential dissemination of many unsavoury ideas. Technology, specifically the internet, has made it virtually impossible to restrict the types and amount of information accessible to individuals no matter how numerous or innovative the firewalls might be. Communication and interaction with the world has reached previously unthinkable levels; experiences are exchanged, public opinion is rallied, decisions are made more quickly, and the world can be made aware of events no matter where they might happen. While this could present a challenge for the GCC on some levels, it can be argued that knowledge has transcended physical and political borders, and is finding its rightful place in societies and minds that are capable of building on it. (11)

Conclusion

As has now become obvious, the interests of countries, the changes they go through, the ways in which societies interact with their governments, ever-increasing political demands, and the sheer complexity of these variables, are all deeply and inextricably intertwined. Every GCC country has internal and external issues that need to be dealt with impartially, and with the involvement of every component of the GCC community if a new social contract is to be accepted and to prove workable.

One cannot help but wonder whether a possible Khaleeji union would be a knee-jerk reaction to internal and external security concerns, or the product of a carefully considered structural, economic, political and social variables. While either response could bring about a GCC union, the sustainability of such a union, and the resources and capabilities that each of the member states would be willing to contribute towards achieving and maintaining it, would be quite different. A union of GCC states remains a possibility, but divergence among its member states also remains strong.

_______________________________________________

* Dr. Yahya Alzahrani is assistant professor at the Naif Arab University for Security Sciences in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

1. See GCC Charter (English translation) at: http://www.gcc-sg.org/eng/index.html

2. Al-Harbi, Turki (2014). The Future of the GCC Union, Naif Arab University for Security Sciences, Saudi Arabia

3. De Montbrial, Thierry and Jean Klein (2000). Dictionnaire de stratégie. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France.

4. First used by US commentator Walter Winchell in a piece titled ‘Howz [sic] about calling the Russians our frenemies?’ in 1953, this term found its way into international relations to describe state behaviours. For more on this, see Saqr, Amal (2014). The Regression of the Friend Vs. Enemy: Duality in the World Order – Future Concepts, Future Center for Advanced Research and Studies, United Arab Emirates.

5. Haykel, Bernard (2013). Saudi Arabia and Qatar in a time of Revolution, Gulf Analysis Paper, 19 February, Centre for Strategic and International Studies, Washington DC. http://csis.org/publication/gulf-analysis-paper-saudi-arabia-and-qatar-time-revolution

6. The US Department of Defense, for example, defines national security as ‘the art and science of developing, applying and co-ordinating the instruments of national power (diplomatic, economic, military, and informational) to achieve objectives that contribute to national security’ (see US Department Of Defense 2007). The issue, however, is not about finding a definition of national security that reflects all of its complexity, but to marry national security with strategic depth when it comes to contentious issues such Egypt and the Muslim Brotherhood. In such instances, the concept becomes very complex and difficult to define. For more, see: US Department of Defense (2005). Dictionary of Military and Associated Terms. http://www.dtic.mil/doctrine/dod_dictionary/

7. http://www.gcc-sg.org/eng/index142e.html.

8. Kauwari, Ali Khalifa et al., (2013) National Policies and the Need for Reform in GCC States, Beirut: Al-Maaref Forum, Beirut.

9. Al-Khatib, Hisham (2010). Global Energy Security and its Impact on the Gulf Region, Abu Dhabi: Emirates Center for Strategic Studies and Research.

10. At the time of writing the price was at its lowest since 2011. See: Badawi, Tamer (2014). Gulf economies and falling oil prices, Al-Jazeera.net, 19 October 2014. http://www.aljazeera.net/news/ebusiness/2014/10/19

11. Abdullatif, Kamal (2012), Knowledge, Ideology and the Network: Intersections and Bets, Beirut: Arab Scientific Publishers.