|

| [AL JAZEERA] |

| Abstract This study examines the factors and variables that are significant in shaping the future of the Islamic State (IS or Daesh) and its fate, in light of US-led coalition’s war against it. This study is based on two main assumptions. The first is that the real success of the current war, in the long-term, will be achieved only through breaking the connection between Daesh and the Sunni community. The second is related to the situation that the entire region is currently experiencing – the region’s transitional phase is causing the official traditional state system to collapse and creating a situation of anarchy and instability, in turn paving the way for the rise of armed militias, particularly those with a sectarian, religious or ethnic nature. The study concludes that militarily eliminating IS will not create a situation of regional stability, nor will it save the Arab state system. Events on the ground indicate that the Arab region is experiencing a period in which the old, official systems are collapsing, without prospects created for a peaceful alternative. Thus, a scenario of violence and political and geographical fragmentation is most likely in the near future, or at least for as long as the consensual, national democratic alternative is not adopted in Arab countries and societies. |

Introduction

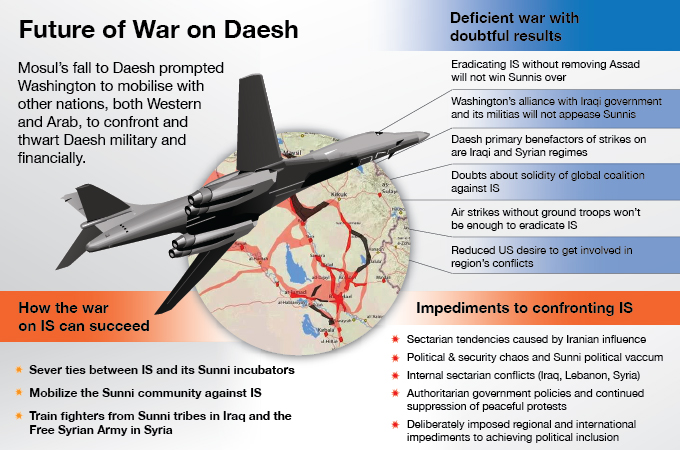

Soon after Mosul fell and with the continuing rapid expansion of Daesh, the US and its allies began changing their approach towards Syria and Iraq. Washington no longer viewed Daesh as a local Iraqi organisation undergoing a structural crisis as it did in 2008. It was no longer just linked to the Sunni community’s inability to coexist with its radical religious ideology, or a group being confronted by the local Sunni Awakening.

Rather, Daesh is now a cross-border regional actor that controls large tracts of land and destroys international borders in order to connect the Syrian and Iraqi areas under its influence. It also possesses significant military arsenal, acquired mostly during its battles with the Iraqi and Syrian armies; boasts extensive military experience and combat efficiency; and has a military component that manages its battles with outstanding professionalism. Daesh has vast sources of wealth derived from the oilfields that it controls, adroitly dealing with the “black market” to escape the severe sanctions that have been imposed. Furthermore, and perhaps most importantly, it shrewdly exploits both the existing regional conflicts and the conflicting interests of regional and global state actors while benefitting from the social cover produced by the spread of sectarianism, anarchy and gaping political vacuum in the Arab world.

The US has reacted to Daesh by mobilising western and Arab countries into a military alliance whose main goal is to cut it off at the knees, halt its expansion and eventually eliminate it. Following years spent denying the fundamental problem that gave rise to such an organisation, recent discussions of the phenomenon’s cause have displayed greater depth of perception. In fact, the US has acknowledged that there was a Sunni crisis in the region which paved the way for rise of IS. Subsequently, the US was able, through regional understandings (particularly with Iran and Saudi Arabia), to reach a deal to remove former Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri al-Maliki, claiming that his policies had consolidated the spirit of sectarianism in Iraq and undermined the institutional legitimacy of Iraq’s new political system.

However, this “solution”, which can only be defined as superficial and restricted, overlooked Iran’s ongoing attempts to entrench its influence not only in Iraq, but also across the Arab region, and particularly in Syria, where it has supported President Bashar al-Assad, and involved Hezbollah and Shia militias in the Syrian civil conflict to save the Assad regime from drowning.(1)

This study identifies the reasons behind the rise of IS in Sunni communities, and discusses the factors and variables that contribute to shaping its future and its fate in light of the current war against it by the US-led international coalition.

Ignoring underlying reasons

The irony is that the coalition decided to attack the organisation in Iraq and Syria together, while ignoring the need to address the underlying reasons behind its establishment and meteoric rise. Those reasons include the Syrian regime's policy of suppressing peaceful protests and the continuous use of all types of weapons against the Syrian opposition. These policies led firstly to the militarisation of the peaceful uprising, secondly to the emergence of al-Qaeda in Syria, which then split into IS and the Nusrah Front, ultimately helping Daesh consolidate its influence. Daesh mastered the sectarian game and took advantage of it in confronting the “other party”, relying on a blatant identity-based discourse in recruiting its large Sunni component. Sunni communities were in a state of despair and extreme frustration due to the absence of any possibilities for apolitical and peaceful change, exacerbated by the international community’s reluctance to intervene despite the tragic situation that has led to millions of refugees, hundreds of thousands murdered, and hundreds of massacres and other disasters targeting Sunnis in Syria.

In the context of increasing reciprocal sectarian tendencies, and with Shia political forces resorting to Tehran as their regional ideological centre-point, the general political weakness of official Sunni capacity was underlined. Since the Sunni communities in the three main countries (Iraq, Syria and Lebanon) felt there was a political vacuum that posed a serious threat to their identity and interests, the rise of the Islamic State is no longer difficult to understand or analyse. Though not necessarily an organic cultural civilisational alternative, Daesh’s success arises from the extraordinary circumstances and prevailing situation of chaos and internal conflict. It has become a self-defence tool for segments of the Sunni community, whether they accept it or not, particularly because they have found no alternative route to effectively resist it.(2)

Consequently, the Sunni crisis remains the core weak point of the Obama administration's strategy in confronting the Islamic State. Sunnis are unwilling, once again, to bet on partial and deficient solutions. In the event that Daesh is defeated, they realise this will lead to further deterioration and failure. However, the Islamic State organisation remains a reflection of Sunnis’ anxiety and panic as a result of the current situation rather than their preference for a system of rule.

Based on its conviction that the war on the organisation is a complex process, and since military dimensions are intertwined with the political ones, the US has developed a long-term vision, linking military progress with loosening the interconnection between Daesh and its Sunni incubators in both Iraq and Syria. In order to translate airstrikes into military gains, the US relies on Kurdish forces, the Iraqi Army and Iraqi and Syrian Sunnis, whom the US and its allies want to train to fight al-Qaeda. Hence, discussions are underway to establish a “National Guard” in Iraq to train Sunni tribal members and incorporate them into it, and also to train the Free Army in Syria.(3)

Multiple questions

This leads us to a fundamental question (from which many other questions stem) regarding the next phase and the future of the Arab region: What are the possible scenarios or future outcomes of the current international war on the Islamic State?

This broad question generates many others about whether the US and its allies will succeed in eliminating Daesh in all the territories under its influence in both Syria and Iraq. And if that is the case, what would the future situation in Iraq and Syria be if the Sunni political problem in Syria remains unsolved, and if efforts to contain the Iraqi Sunnis fail? Will the elimination of Daesh truly help restore regional stability, the underlying and fundamental problem in the Arab world?

Before trying to answer this fundamental question and its multiple sub-questions, it is necessary to mention four aspects of the organisation and the underlying reasons behind its rise:

-

Daesh’s rise as an active regional, trans-state and community organisation is due to two main factors. The first is the prevailing sectarian mind-set in the region arising from Iran’s regional influence, the Sunni political vacuum, and the slew of internal conflicts based on sectarian, religious and ethnic divides in both Iraq and Syria. The second is linked to the general Arab political crisis in the region, and stems from the authoritarian regimes that continue to suppress peaceful protests, resulting in a political stalemate, as well as the counter-revolutionary movements against the Arab Spring’s outcomes.

-

The organisation may be viewed as one model among multiple models of cross-community groups. These are many religious and sectarian entities that have become actors amid the prevailing political and security chaos. In fact, Shia groups in Iraq, Hezbollah, Kurdish groups, Salafi-jihadi entities, al-Qaeda branches and the Houthis all arose from similar political and societal conditions that led to the rise of Daesh.

-

The political, security and military role of such groups is founded on the failure of the Arab national state in the fields of political integration, the protection of citizenship values, and rule of the law. This failure feeds instability and the political vacuum.

-

The rise of this organisation, both locally and regionally, is not surprising, and its successful elimination must go beyond military and security aspects, addressing the substantive political factors that underpin its appeal and that of similar organisations.

Two important conclusions can be drawn from the above observations:

-

The long-term and actual success of the current war will not be achieved unless the interconnection between Daesh and the Sunni community is unravelled. There is also the question of the extent to which Sunnis are prepared to once again rise against the organisation, as occurred with the Sahwa (Awakening) groups in 2007.

-

The entire region is undergoing a transition period where the official state and its political system have collapsed. This goes beyond Iraq and Syria to include most countries of the region, with chaos and instability also prevalent in Yemen, Libya, Lebanon and the Sinai Desert in Egypt, where armed militias with a sectarian, religious or ethnic nature are gaining ground.

Factors affecting the international and regional coalition

The scenarios for the coalition and its next steps are somewhat ambiguous, as it faces substantial dilemmas, the most important of which are:

-

First, the US administration is aware that eliminating or weakening Daesh without extending its goals to include the Syrian regime will not convince the Sunni community to change its stance and actively participate in defeating the Islamic State. So long as President Obama does not address the Syrian regime’s policies or force it to step down, the Syrian Sunni community sees no light at the end of the tunnel, and the reasons behind the rise of this powerful organisation will persist. Turkey has made it clear that a pre-condition for its full engagement in the coalition against IS will be a strategy including the removal of Assad’s regime, and this approach is also supported by France. By contrast, any declaration by the US administration that the war would target Bashar al-Assad's regime would drag it into a dual conflict, with Iranian sympathisers and IS simultaneously, and may also lead US allies in the Iraqi government to oppose such a move.

-

Second, in its attempts to weaken and destroy Daesh, the United States is allying with the Iraqi government that supports Iraqi militias who adopt a counter-sectarian approach to Daesh, committing similar violations as the group against Sunnis. Baghdad is also allied with Bashar al-Assad and Hezbollah in confronting Daesh in Syria. Such cooperation, whether direct or indirect, in achieving a common goal between the US administration and these factions, will not help to reassure the Sunnis, nor will it give them an incentive to change the status quo so long as they feel that their identity in these regions is under an existential threat.(4)

-

Third, given the slow progress towards a political solution, how can the US administration convince the Sunni community that this war serves their interests rather than that of their opponents, especially since the immediate beneficiaries of the strikes against Daesh are the Iraqi and Syrian regimes? Furthermore, in the event that IS is vanquished, what guarantors does the Sunni community have that these regimes would not again turn against it, as occurred previously after they succeeded in weakening Daesh through the Sunni Awakening? The Sunni tribal Sahwa (Awakening) is being reproduced as the “National Guard”, but it may have already lost a strong support base from which to recruit and rebuild the balance of power. The Sunni community does not necessarily accept the National Guard, particularly given its clearly religious and political agenda.

-

Fourth, there is significant uncertainty regarding the strength of the regional and international coalition against the Islamic State. Despite the fact that dozens of countries are involved in the air strikes, coalition members have different visions based on their interests, particularly within the region. Turkey did not accede to land intervention to save the Kurdish city of Kobani, and it did not allow coalition planes, during the initial period of air strikes, to use its air bases. This is because Turkey adopts an approach that aims to not only eliminate Daesh, but also to remove the Assad regime in Syria. The Arab states, especially Saudi Arabia, are concerned about Iranian influence and the relationship of the new Iraqi regime with Tehran, thus they take a tough stance towards Assad’s regime. Although they view Daesh as the main threat to their national security and regional stability, they also perceive Tehran as a real threat to them, which will create cracks in the international coalition if the war is prolonged, and the US administration has already indicated it will be.(5)

-

Fifth, despite the importance and impact of airstrikes, in the long term they will be unable to completely eliminate Daesh without ground troops. Plans to train the Sunnis in Iraq and Syria to confront IS still face considerable political and technical difficulties and complexities. The planned development of the National Guard in Iraq requires years in order to be fit for confrontation, while the Free Syrian Army (FSA) in Syria is still weak and unable to take advantage of Daesh’s weakening during the military and geographical siege. Moreover, it is still unclear how the war and its goals will develop if political efforts to reduce the Sunni crises in both countries fail.(6)

-

Sixth, the current global and regional context has significantly lessened the US’ appetite for involvement in new wars, somewhat in line with Obama’s promises to the American public. This is reinforced by the growing conviction within American political and intellectual circles that the entire region is experiencing a disintegration of the Arab geo-political system formed in the wake of World War I, and that the Arab nation-state has failed, which makes attempts to maintain the status quo difficult. Perhaps this was best expressed by US President Obama himself in an interview with American journalist Thomas Friedman, when he said, “What we’re seeing in the Middle East and parts of North Africa is an order that dates back to World War I starting to buckle”.(7)

These factors raise doubts on the current coalition’s continuity, sustainability and ability to deal with diverse impacts of the prevailing disintegration and chaos. These doubts are heightened by strategic analyses that point to the declining relevance of the Arab world to vital US interests, particularly given the discovery of large oil reserves within the US itself.(8)

Factors affecting Daesh’s organisation

The Islamic State has been able to minimise the effects of the initial military attack, and reduce the extent of the damage caused by airstrikes to date, but faces a real problem during the next phase. Despite the strength shown by its fighters in the Anbar Governorate and the city of Kobani, the organisation has failed to achieve further swift and easy victories, similar to those that occurred with the seizure of Mosul, Tikrit and a large swathe of Sunni territory. Today, it is surrounded on different sides, and is fighting on many fronts, which may exhaust it in the long run, and reduce its financial, logistical and tactical potential in the event that the international and regional alliance maintains its momentum and support from other parties.

Although the organisation has maintained its strength and cohesion, and its members remain committed to the leadership, its major recent expansion may be completely counterproductive and may backfire internally. According to western reports, a large number of followers joined the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria after its military victories and proclamation of the Caliphate. This creates a certain disparity in members’ commitment, and leads to vulnerability. What’s more, if the organisation is defeated and suffers substantial military losses, and its influence declines during the next phase, it is very likely to lose a large number of followers and tribes which had pledged allegiance to it for pragmatic rather than ideological reasons. This will have a negative impact, similar to that of the Sahwa era in 2007 when its influence waned after a large number of adherents defected.

However, the organisation’s weakest point, and perhaps its Achilles heel, is its relationship with the Sunnis. If a large part of the Sunni community defects from it, either for political reasons or in rejection of the religious ideas and lifestyles it imposes on society, the very reasons behind its rise will lead to its decline and downfall.

The organization is fully aware of the importance of the “Sunni incubator”, and the debilitating blow that it suffered from the Sunni Awakening in the past. Therefore, it has been zealous in purging the geographical areas under its control, by imposing its influence and abolishing other groups, forcing them to pledge their allegiance to Daesh. Indeed, the group has prioritised the struggle against opposing Sunni factions in its combat strategy (giving priority to killing apostates before dealing with any other opposition, a key foundation of its ideology). However, this approach itself carries the seeds of failure and collapse, since it is premised on fear and power rather than conviction and consensus. Indeed, this exposes Daesh’s relationship with the Sunni community as temporary and forced that is not based on any type of deep strategic and cultural choice.

The sociology of violence: the organisation as a “model”

Researchers and politicians usually commit a cardinal error when they analyse the rise of Daesh in the region without linking it to the general political context of the region. The organisation’s violence and severe conduct is not an oddity, but is instead part of the current wave of “structural violence” sweeping many Arab countries and societies.(9)

It is essential to tackle this new political actor within the framework of authoritarian violence, whether it is of a sectarian nature, as in Iraq and Syria; or generally oppressive, as is the case in Egypt, Algeria and other Arab countries; or occurs within the context of the structural crisis faced by Arab states, and creates popular feelings of marginalization, exclusion, the absence of peaceful prospects, and appalling economic and social conditions.(10)

It is also necessary to view the rise of Daesh within the context of chaos raging in Libya, and the political vacuum and the growth of Salafi-Jihadi groups there, as well as in the Sinai desert and Yemen. Houthi control over Sanaa, as well as the Bahraini crisis and other internal crises in Arab countries, are further contexts that must be included in any complete. Today, there is a growing disintegration of societies, accompanied by the collapse of the moral authority of the state, and a return to older forms of expression of identity.(11)

Such climates the Islamic State “model” and make it an attractive option that can be cloned and applied in many societies as long as alternative paths are closed. The danger of this organisation is not only because it crossed borders, set up a trans-border entity, and is brutal with its opponents, but also because it has become a model that reflects the negative, violent trends and the situation in Arab and Muslim communities.

That Daesh has become a so-called model is evident from the fact that other groups in Libya, Yemen and Egypt have sought to reproduce it. As long as the Sunni political crisis is not resolved and the Arab authoritarian crisis persists, this organisation and others like it, whether of the Shia persuasion or loyal to other ethnicities or religions, will find fertile ground to germinate, rise and adapt to pressure and various circumstances. Furthermore, even if they decline in one region, they rise elsewhere if these conditions remain.(12)

During the Afghan war starting 2002, the US and its allies managed to eliminate the rule of the Afghan Taliban, and to destroy al-Qaeda strongholds and disperse its leadership, but the problem quickly reappeared a few years later. In fact, American circles today recognise the fact that the political process in Afghanistan has been unable to bring stability to the country. They also assert al-Qaeda and its multiple offshoots, including the organisation of the Islamic State (which split from al-Qaeda), are becoming more prevalent, omnipresent and powerful, despite all the security, military and economic efforts to combat them.

Conclusion

To conclude, it is clear that eliminating the Islamic State militarily will not bring about regional stability, nor will it save the official Arab state. Realistic analyses indicate that we are facing a stage in which old systems are collapsing, without creating prospects for peaceful alternatives, which could have been provided by the Arab revolutions for democracy. However, with constant challenges to these revolutions’ paths, the scenario of chaos, violence and political and geographical fragmentation (based on primitive identities) is the most likely in the near future. As long as the democratic, national and consensual alternative is not available in most Arab countries and communities, the region will remain enmeshed in a vicious cycle of internal and regional conflicts and excruciating crises.(13)

_______________________________

Dr. Mohammad Aburumman is a researcher specialising in the study of Islamic groups.

Endnotes

1. Bozorgmehr Sharafedin, “Why Iran Abandoned al-Maliki in the End”, BBC Arabic, 13 August 2014: http://www.bbc.co.uk/arabic/middleeast/2014/08/140813_iran_let_maliki_go.

See also: “Obama criticises al-Maliki and sends 300 military experts to Iraq”, Al-Araby Al-Jadeed, 19 June 2014.

2. This does not imply, in any way, a Sunni acceptance of this organisation and its discourse and conduct. The battles which occur in Syria and Iraq between other national and Islamic factions against the Islamic State influence are evidence of the internal resistance against it, the rejection of it and the prevailing attitude that it pose a serious political and cultural threat to the Sunni community’s fate and interests. However, events and developments demonstrate that the current trajectory serves IS more than it does its opponents within the Sunni community, who are stranded between concerns over their Sunni identity as a result of the political and sectarian threat, on the one hand, and the rise of this organisation and the magnitude of the danger it poses to the culture, lifestyle and interests of a peaceful society, on the other.

3. David Ignatius, “Obama Faces Growing Pressure to Escalate in Iraq and Syria”, Washington Post, 14 October 2014.

4. Robert Baber, “Even if We Kill Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, Who Will Extinguish Sunni Anger in the Middle East?”, BBC Arabic, 2 November 2014, http://arabic.cnn.com/middleeast/2014/11/02/commentary-baer-isis-assassination.

5. Hebsi Al-Qudsi, “Washington Rejects Turkish Conditions to Set Up a No-Fly Zone or Buffer Zones”, Washington Post, 7 October 2014.

6. Mustafa al-Obaidi, “Divergence of Iraqi Political Groups’ Stances Vis-à-vis the Establishment of the National Guard to Combat Terrorism”, Al-Quds al-Araby, 17 September 2014.

7. Thomas Friedman, “Obama: Iraqi Shias squandered the opportunity”, Al-Sharq al-Awsat, 12 August 2014. Thomas Friedman’s full interview with President Obama can be found here: http://www.nytimes.com/2014/08/09/opinion/president-obama-thomas-l-friedman-iraq-and-world-affairs.html.

8. Various reports on the region’s future attest to this:

Robert Kaplan, “The End of The Middle East”, Real Clear World, 30 October 2014, www.realclearworld.com/articles/2014/10/30/the_end_of_the_middle_east_110774.html.

Aaron David Miller, “Middle East Meltdown”, Foreign Policy, 30 October 2014.

Economist.com, “Why Post-Colonial Arab States are Breaking Down”, Economist, 1 October 2014, http://www.economist.com/news/middle-east-and-africa/21623771-why-post-colonial-arab-states-are-breaking-down-rule-gunman.

9. Aaron David Miller, “Middle East Meltdown”, Foreign Policy, 30 October 2014, http://www.foreignpolicy.com/voices/miller.

10. Chuck Freilich, “The Middle East Heads Towards a Meltdown”, The National Interest, 26 June 2014, http://nationalinterest.org/feature/the-middle-east-heads-towards-meltdown-10753?page=2.

11. Glenn Greenwald, “How Many Muslim Countries has the US Bombed or Occupied since 1980?”, The Interception, 11 June 2014, https://firstlook.org/theintercept/2014/11/06/many-countries-islamic-world-u-s-bombed-occupied-since-1980/.

12. See for example: “Ansar Bait al-Maqdas joins Daesh and pledges allegiance to Al-Baghdadi”, Al-Hayat, 10 November 2014. Also, “Daesh in Derna, Libya …Sharia Court and Wooing of Officers”, Al-Safir (Beirut), 22 October 2014.

13. Murtaza Hussain, “The Middle East’s Unholy Alliance”, The Intercept, 11 April 2014,

https://firstlook.org/theintercept/2014/11/04/middle-easts-counterrevolutionary-alliance/.

| Back To Main Page |