|

| An anti-austerity protester at a rally in front of the parliament in Athens, Greece [AP] |

| Abstract Following the referendum held on 5 July 2015, Greece’s Prime Minister, Alexis Tsipras, has been able to strengthen his position since he no longer has political opponents inside Greece. The European institutions, however, are maintaining a very inflexible stand towards him and towards his country, while Turkey continues to be provocative with its violations of Greek airspace. Today, Greece faces a serious challenge: will the country remain in the Eurozone and the EU, or will it throw in its lot with Russia, join the BRICS group and transform the geopolitical, economic and political balance as we know it? |

The Hidden and Coming Financial Storm

Greece is a country that has been involved in many wars with its neighbours over the years. After its liberation from the Ottoman Empire, Greece’s infrastructure and economy were poor and its sole option was to accept loans from other European countries. Since 1823, when the country accepted its first loan from Britain, Greece has obtained numerous other loans at different historical periods. It is important to note that, since 1923, Greece has failed to meet its debt obligations four times(1). It is within the bounds of possibility that Greece may now add one further bankruptcy to its history. The difference today is that such a bankruptcy would be inextricably linked with an exit from the Eurozone and the European Union in what is being called a “Grexit”.

Since 2008, Greece has suffered the effects of the global financial crisis. As one of the weakest economies of the European Union, Greece is among the countries which have been affected the mostIn 2010, the prime minister at that time, George Papandreou, signed the first “memorandum of understanding” with the Troika, which consists of the European Union (EU), the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the European Central Bank (ECB). Since then the country’s debt has increased from 120 per cent of GDP to 180 per cent of GDP(2), and Greece has undergone a gruelling experience resulting from the necessity of taking austerity measures to be able to repay its debt and restore itself to an economic footing acceptable to its creditors.

This has been the situation until recently. However, in the elections of January this year, the majority of the Greek people voted in favour of the left-wing party Syriza and Alexis Tsipras became the new prime minister. The new government adopted a different strategy, with a refusal to sign up to a new bailout program from the IMF and the EU that would have led to a new era of harsh austerity and economic decline. Instead, it proposed a plan that would promote economic development and investment, and the reduction of unemployment. At the end of June, the country failed to make its scheduled payment to the IMF, with the result that the ECB placed severe restrictions on the money supply to the Greek financial system. Consequently, the government was obliged to implement capital controls on the Greek banks. On 5 July followed the referendum in which the Greek people voted in favour of the government’s strategy of opposition to austerity.

Geopolitical Changes

Russia

On 8 April 2015, the Greek Prime Minister visited Moscow in an attempt to enhance Greece’s geopolitical position with an agreement with Russia on the extension of a Russian gas pipeline through Greek territory. Additionally, Russia has offered to make an exception for Greece regarding its embargo on European agricultural produce after the Ukrainian crisis. In addition, in numerous diplomatic meetings in relation to co-operation with China, Greece has made clear its willingness to join the BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa). Kostas Isichos, deputy minister of Defence, explicitly declared that Greece is open to the possibility of becoming a member of the BRICS group(3).

Russia will not be reluctant to extend its influence to a country with a Mediterranean coastline, breaking the restrictions on Greece imposed by the West and breaching its isolation, either alone or with allies from within BRICS. Following the outbreak of the crisis in Ukraine and the Russian annexation of Crimea, it is clear that the Russian leadership has no interest in exercising restraint; in fact, Russia’s desire is to increase its influence in the global economic and political field.

Russia appears willing to fill the Greek financial gap, by investing in the future of a post-“Grexit” Greece in a number of ways: by investing in large-scale public and private projects, with the import of Greek agricultural products, and the enhancement of Greek liquidity through the promotion of tourism, and through the provision of Russian technical experience and capital to extract natural gas from the Mediterranean. What Russia will ask in exchange is for Greece to permit a Russian military presence and to host Russian logistic support for its Mediterranean fleet in Greece’s seas and islands. History has demonstrated that Russia is always more than eager to enter the Aegean Sea and the Bosporus. This was the principal reason for past conflicts between Russia and Turkey. Russia made it clear that Greece would have access to finance from the proposed New Development Bank operated by BRICS if it formally becomes a member with the purchase of a small shareholding in the institution. The bank, which is set to begin operations next April, is seen as an alternative to Western financing(4). An additional factor is that Russia shares religious and cultural characteristics with Greece.

Turkey

A hypothetical “Grexit” would change the geopolitical balance in favour of Turkey. At present, Greece’s borders are regarded by the EU as Europe’s frontiers, which is why FRONTEX, the European Union’s border police and military control unit, has a strong presence in Greek territory(5). If Greece leaves the EU, this could no longer be relied upon. A further major problem is that the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) that is claimed by Greece would immediately be subject to challenge by Turkey. At present, Europe supports Greece’s claim to its EEZ, which in 2013 the European Parliament voted to recognize(6), with the implication that only Greece is entitled to exploit the natural resources of the Aegean Sea, to the exclusion of Turkey. Dating from the Imia crisis of 1997, Turkey has a history of challenging both Greece and Cyprus’s EEZ rights. In 2014, for this reason, an alliance was established that includes Greece, Cyprus and Egypt, which sympathises with the Greek position.

Turkey has on many occasions disputed Greece’s sovereignty and continues to do so. A hypothetical “Grexit” would cause internal disruption within Greece and impair its economic ability to protect itself. Turkey would be sure to take advantage of such a situation to enhance its influence and expand its borders. Outside Europe, Greece would be isolated in the face of its enemies and would naturally turn to Russia to seek military and financial support. A hypothetical alliance with Russia could lead to a Greek withdrawal from NATO, thus removing Greece from the alliance of which Turkey is also a member and potentially raising the level of hostility to Greece in the southeast Mediterranean.

The Greek Referendum

When Alexis Tsipras held the referendum on 5 July, in order to strengthen his negotiating position, 61 per cent of the electorate voted to reject the latest proposal from the European institutions. This was a defeat for his opponents, both within Greece and in European and international institutions. After the referendum, the Greek government reopened negotiations with the European institutions but neither party initially appeared to be willing to back down, making the possibility of a “Grexit” more real than ever before. Alexis Tsipras’s new proposal consisted principally of the following points(7):

• Reduction of the Greek debt by 30 per cent

• Maintenance of value-added tax (VAT) rates in the Greek islands at 13 per cent

• No reduction in defence expenditures before 2016

• No reduction in pensions and salaries

• The provision of new finance of 30 billion euros, sufficient to continue the development program and service the IMF loans

EU Weaknesses

Agreement between Greece and its creditors is difficult owing to the European Union’s inability to agree on a common position. There are five principal reasons for Europe’s divisions.

(1) The European states have differing national identities and have no sense of common “European-ness”.

(2) The European Union does not have a single economy; it has many economies of different sizes, which are in competition with each other.

(3) There is no financial parity; the economies of Europe’s northern states are far more developed those of its southern region, of which Greece forms a part.

(4) The nations of Europe have a long history of rivalry and conflict, which has led to issues of mutual prejudice and mistrust between the European Union’s member states. (It is worth noting that, according to the Greek Ministry of Economy, the level of German war compensation due Greece in consequence of Nazi occupation during World War II stands at 278.7 billion euros. Although this issue has recently been raised once more by Greece, Germany refuses to address or even discuss it.)

(5) Bureaucratic procedures within the EU involve a considerable level of complexity, a factor that inhibits rapid decision making.

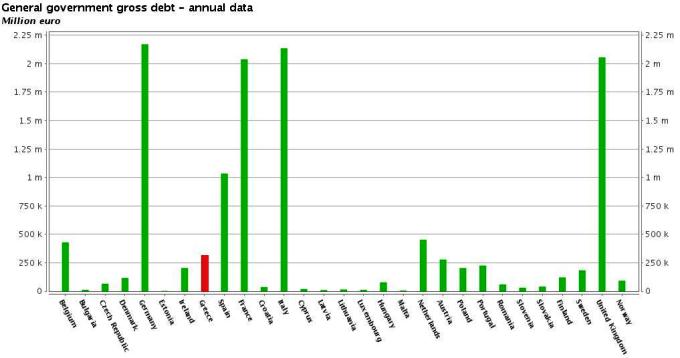

For all these reasons, it is very difficult for the states that make up the European Union to share a common culture, and making the EU no more than a “club of states”. It is also of real significance that all the European states are deeply in debt, to a much greater extent than Greece, as can be seen below in Figure 1.

|

| Figure 1. The general government gross debt of the European Union'0s 28 members- comparing to Greek debt )(8) |

Despite the Greek people’s endorsement of and support for the Greek government, and notwithstanding the presence in Europe of 23.3 million or more unemployed citizens, of which more than 2.5 million are in Greece, the European élite will continue its interminable discussions without producing a solid solution for Greece’s social, political and economic problems. Instead, it is likely that they will succeed only in producing ad hoc solutions, in line with the toxic strategies favoured by the IMF like cutting government jobs and increasing taxes, while decreasing pensions and salaries.

During a five-year period of austerity in Greece, European institutions have continued their discussion of the issues in hundreds of separate committees only to reach a dead-end. The European élite purported to be offended by the casual dress-code adopted by Tsipras and Greek finance minister Yanis Varoufakis, while paying no attention to the failure of the combined financial expertise of the northern states to solve a problem relating to a mere two per cent of the European economy, the most serious challenge they currently face. The European élite joined forces in an effort to overthrow the left-wing government of Greece after five months of vacuous and futile negotiations. They also illegally interfered during the Greek referendum, employing every possible stratagem to support the opposition, while blackmailing and threatening the Greek public and exerting pressure on the Greek government to replace certain ministers. While this attitude persists, there will be a vicious circle in which Greece’s problems will continue to escalate.

The United States and the EU

In past situations of this kind, it has been necessary for the United States to play a mediatory role and exert pressure on the EU member states in order to bring about a resolution fortheir problems. Some obvious cases have been the resolution of the Northern Irish problem and the conclusion of the Yugoslav conflict, as well as periodic interference in the Greek crisis. It was for this reason that the US exerted a high level of pressure on Germany while seeking French intervention in order to resolve Greece’s difficulties in such a way as to enable Greece to remain a member state of the European Union. The established strategy of the US has always been that America should have a role in Europe while Russia should not, and that German predominance should be minimised.

What would a “Grexit” mean for the Eurozone?

The most significant longer term consequence of a hypothetical “Grexit” would be that the European Union would be radically changed without Greece, which all member states agree is a crucial component of Europe’s historical and cultural heritage. A “Grexit” would also most probably be catastrophic in economic terms, since the global stock markets would react in panic and the world could conceivably face a new economic crash that would be worse than the consequences of the bankruptcy of the Lehman Brothers in 2008. Europe could lose more than 240 billion euros through lost investments, falls in stock market valuations, the bankruptcy of enterprises and currency depreciation. There are three main reasons for this. First, Greece is part of a global financial system based on international transactions. Financial globalisation has meant that all countries are vulnerable to changes which may have taken place anywhere in the world. A “Grexit” could lead to financial meltdown in Europe, the United States, China, Russia, or even countries that do not appear to be connected such as India and Canada. Second, Europe is unprepared for a “Grexit” because it has not yet found a way to isolate the damage. Europe’s leaders cannot estimate the consequences of a possible “Grexit” because they are simply not possible to measure. Finally, if Greece were to exit the Euro, European lenders and the IMF would be left with a vast hole in their budgets because, as a bankrupt country, it would not be in a position to repay any of its debts for at least twenty years.

Aside from financial considerations, the EU also faces the implications of a hypothetical “Grexit” for the Union’s coherence. What the EU’s political leadership knows is that other countries will sooner or later follow Greece’s lead. Since the European Union has evolved into a struggle for power and profit, most of the northern EU countries, such as Germany, are making profits at the expense of the so-called PIGS (Portugal, Italy, Greece and Spain). These are the countries that have suffered the most to keep the EU’s currency strong and competitive against the US dollar.

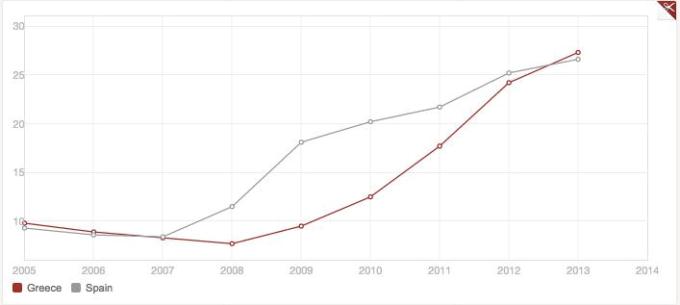

EU leaders are aware that PIGS would be the next to exit the monetary union of the Eurozone and possibly the Union itself. After Greece, the country which is closest to an exit is Spain. Spain has a very strong and popular left-wing opposition party called Podemos that is already represented in parliament. Elections are scheduled for the end of 2015 and Podemos appears to be gaining ground thanks to the demand in Spain for political renewal and an end to austerity. Spain has many points in common with Greece. Unemployment in Spain has reached 22.7 per cent in 2015, from a level of about eight per cent in 2007(9).

|

| Figure 2. Comparison of the unemployment growth between Spain and Greece 2005-2014(9) |

Harsh austerity measures have been taken in Spain at the behest of the EU in order to re-balance the country’s financial position, but the strategy has failed. Spain’s debt-to-GDP ratio has doubled since 2006(10). If Greece exits the Euro, other member countries will take advantage of the precedent and will follow the same route out of a Union into which they can no longer comfortably fit. With this scenario, the EU could soon be facing its own demise since some of its core member states may leave.

|

| Figure 3. Comparison between the Debt to GDP Ratio of Spain and Greece(10) |

The Internal Impact of “Grexit”

At a regional level, if Greece were to leave the Eurozone, the country should be ready to deal with any urgent issues that may arise. The banks may remain closed for a long period of time and financial liquidity will be reduced gradually. There may be a major problem with trade (both imports and exports), since suppliers will not give credit and there will be no money supply inside the country. As a result, many products will cease to be available and the market will be drained of imported products. This may lead to social unrest, which the government should be prepared to deal with. In addition, the country will be obliged to allow emigration to Europe, since it will be unable to control its borders effectively. Further, due to the lack of liquidity and absence of demand, many small businesses will close with a concomitant increase in unemployment. All these factors will continue to prevail for a substantial period.

However, as soon as Greece reverts to its own currency, the situation may change drastically. Liquidity will return to normal, the banks will reopen and exports will resume. New businesses will be able to start up, especially in the agricultural sector and production industries. Thus, new jobs will be available and unemployment will be reduced. As valued in local currency, locally made products will be affordable in relation to salaries but all foreign imports will become vastly more expensive. Without the burden of its debt, the country will be able once more to stand on its own feet and make a fresh start. Overall, however, the outcome will depend on the government’s ability to manage its exit from the Eurozone and the modalities of the readoption of its own currency.

A Feasible Solution

A realistic solution to the crisis would be a reduction of 70 per cent in the level of Greece’s debt. It should be stressed that there is a highly relevant precedent for this. After WWII, Germany’s debt was erased by its creditors, which included Greece, and the Marshall Plan of 1948 provided funds for Germany to restructure its economy(11). In addition, Europe should offer 50 billion euros for development projects, thus assisting Greece to regain its share in the international market and confront its unemployment problem, and allowing it to invest in the extraction of natural resources in its territory, both on land and at sea. At the same time, the economic and financial institutions of the Greek state need to be entirely reconstructed. Finally, the Greek government should introduce new legislation to attract foreign investment.

The European Union will undoubtedly persist in its failure to devise a feasible and realistic solution for the Greek crisis, and any proposed solution will be identical to or worse than those proposed in the last five years. In the years to come, there will continue to be problems and tension between the northern and southern countries of Europe. A Greek exit will initiate a domino effect that could lead to the departure of other European states from the Union and the weakening of the EU. In such a case, unemployment figures will deteriorate and the income gap between rich and poor will widen. The United States will continue to be a dominant force dictating the policy of the European Union. On the other hand, BRICS will begin in the coming years to compete with the IMF. Russia will continue its attempts to play a role in Europe, using finance and its role as a natural gas provider to influence EU member states. The impact of a “Grexit” on psychological market factors, the maintenance of public order, and even the geopolitical status quo cannot be predicted by technocrats. What is required, therefore, is a political solution.

Postscript

Although the Greek people have rejected the proposals of the Troika at the referendum on 5 July 2015, the government of Alexis Tsipras made a further proposal to the European Stability Mechanism on 8 July which put forward new proposals in what many commentators described as a stunning U-turn. The finance minister left the government. Effectively, the new Greek proposals were very similar to those rejected in the referendum. On Sunday 12 July, the European negotiators said the proposals could be considered if they were ratified by the Greek Parliament. The Parliament accepted the proposals in the early hours of Thursday, 16 July, with the opposition's support. The measure passed by 229 votes to 64, with 38 members from the ruling Syriza party voting against it, including Varoufakis. The immediate result was riots in the streets of Athens, while EU negotiators agreed on bridging loan that would enable Greece to avoid an early default on debt payments that were due on 20 July. With the future of bail-out talks over Greece’s major debt still in doubt, the future remains uncertain.

______________________________________________

Copyright © 2015 Al Jazeera Centre for Studies, All rights reserved.

* Abdellatif Darwish is a Professor of Economics and Crisis Management at City University of Seattle, in Athens, Greece.

References:

1) Andreadis, A., History of the National Loans. Part A. The Loans of Independence (1824-1825), Athens, 1904.

2) GDP per Capita. World Bank National Accounts Data and OECD National Accounts Data Files. 2015.

3) “Greece Open to Becoming BRICS Member.” www.enikos.gr. June 2015.

4) Mukhopadhyay S. “Greece Can Easily Get Funding From BRICS Bank, Russia.” International Business Times. July 2015.

5) Pavlopoulos. “The Greek Borders are European Borders.” Proto Thema. April 2015.

6) “European Parliament; Greece’s EEZ is European as Well.” Imerisia. March 2013.

7) “What is Included in the New Proposal of the Greek Government.” www.newsbomb.gr. July 2015.

8) "General Government Gross Debt: Annual Data." Eurostat. July 2015.Retrieved from the website http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/tgm/graph.do?tab=graph&plugin=1&pcode=tsdde 410&language=en&toolbox=data

9) "Unemployment total as percentage of total labor force." World Bank National Accounts Data and OECD National Accounts Data Files. 2015. Retrieved from the website http://databank.worldbank.org/data//reports.aspx?source=2&Topic=10

10) "General Government Debt to GDP Ratio." World Bank National Accounts Data and OECD National Accounts Data Files. 2015. Retrieved from the website https://data.oecd.org/gga/general-government-debt.htm

11) Carew A. Labour under the Marshall Plan: the politics of productivity and the marketing of management science. Manchester University Press. 1987.