|

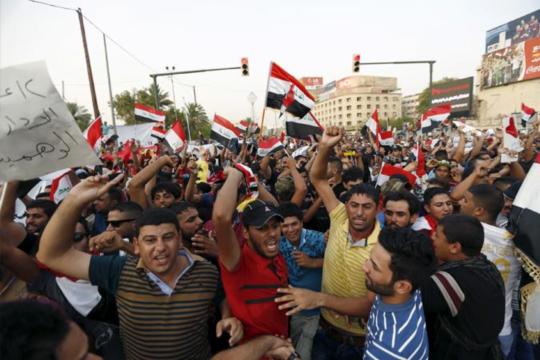

| Recent protests in Iraq present the first large-scale challenge to the Iraqi political system after US occupation and Islamic State [Reuters] |

| Abstract A wide wave of popular protest has recently sprung up in Iraq, particularly in Shia-dominated cities, against deteriorating services and government corruption. These protests have put pressure on the political class to change its agenda and introduce reforms, especially after the country’s top Shia cleric announced his support for the protesters' demands. The protests represent a challenge to the Iraqi government’s ethnic, sectarian and party quota system. They affect (and are affected by) intra-Shia divisions and conflict between the pro-Iran factions, who seek to improve their respective positions in the balance of power. Furthermore, they affect relations between the top Shia cleric and those close to Shia religious families who seek to stabilise the system and adopt gradual reforms. The future of political reform in Iraq depends both on the protest movement’s ability to maintain its momentum and on the extent to which Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi can challenge the current consensus on the political system and the party quota system. |

Introduction

The wave of popular protests in Baghdad and other Shia-majority cities in Iraq can be considered from two angles. Firstly, these protests are the first large-scale popular challenge to the consensus on the Iraqi political system after US occupation. Secondly, they express tension and an internal Shia division on two levels: first, on the relationship between the grassroots community and the Shia political elite and its associated centres of power; and second, on the relationship between these centres of power, resources and influence, and the government’s political ideology and foreign relations.

Roots of the quota system

After 2003, the Iraqi political system was established on the basis of a power-sharing arrangement, which theoretically resolved the distribution of power and the need for decentralisation by establishing national coalition governments representing the different ethnic, religious and sectarian identities making up Iraqi society. However, in practice, the consensual arrangements have been transformed and the idea of power-sharing has become what critics call a “quota” system – where control of state institutions and government and independent bodies are shared according to a proportional representation components equation. This system aims to guarantee that principal dominant forces of each sub-group will always be represented within the institutions of governance, in order to manage power relations. Since its establishment, this system has formed the basis for successive governments.

Along with this kind of power-sharing, “party-sharing” has also become a part of the political system, with each “component” managing the distribution of positions among its various parties and forces. Under this arrangement, however, some of those positions have been gradually usurped by certain political parties, who then become the representative quota. For example, the post of Iraqi president was allocated to the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK), while the post of prime minister was given to the Dawa Party. Due to these arrangements, successive governments have been characterised as heterogeneous, with senior and mid-level positions assigned on the basis of party members’ and supporters’ affiliations and connections, rather than according to professional competence and experience. Political parties have utilised their control over parts of government ministries and institutions to exploit resources by directing state contracts to party-affiliated companies and businesspeople, increasing the numbers of supporters and loyalists through patronage of government jobs.

Due to the rentier nature of the Iraqi economy – in which the revenue from oil, a state-controlled sovereign commodity, constitutes ninety-six per cent of government income – distribution of oil revenues to institutions under political parties’ control implies distribution of a portion of these revenue to the parties themselves. Thus, each party endeavours to grab the largest possible share of resources as a means of strengthening its political influence. It is known that the dominant elites in rentier states, including the governing authorities, succeed in directing economic activity and act independently of the needs and demands of society.(1)

Since the current political consensus is based on the same elitist arrangements, or what Arend Lijphart calls the “elite cartel”(2) – this convergence of quota systems and rentier economies has effectively produced record numbers of corrupt governments. Furthermore, it has led to a culture of clientelism in the political and economic sphere. It has affected the spending behaviour of the political elite, which is characterised by leaders’ pursuit of extravagant personal enrichment and reliance on massive phalanxes of security personnel for personal protection. All these factors provide extensive opportunities for the abuse of power.

Economic crisis

The situation in Iraq has faced widespread popular criticism from the Iraqi public for some years. In recent months, this criticism escalated to public protests due to an economic crisis in the country since the fall in oil prices during the second half of 2014, when the price per barrel of oil fell to forty-five per cent of its previous value. Suddenly, Iraq had to move from an economy of extravagance, wastefulness and consumerism – exacerbated in recent years by the recovery in oil prices – to one of austerity and cost-control. Due to quotas, mismanagement and lack of accountability that came about from a system which distributed power over state institutions on the basis of party loyalty, hundreds of billions of dollars have been wasted in recent years via corruption and failed projects.

Mazher Mohammed Saleh, an Iraqi economist and adviser to the Prime Minister, noted earlier this year that the ratio of projected investment projects to actual implementation expenses after 2003 did not exceed twenty per cent, with around ninety per cent of these projects approved without any prior economic study of their feasibility.(3) Clearly, the appointed managers’ lack of administrative competence – due to patronage appointments based on party loyalty – handicapped the parliament’s ability to account for and safeguard the integrity of government institutions. This occurred due to a tacit agreement among leadership figures, regardless of what each achieved within his sphere of influence, opening the door wide to corruption and a drain on resources. In recent years, a new class of entrepreneur has emerged, attaining wealth through government contracts or relationships with government officials. This practice has shaped the Iraqi leadership’s political and financial relations on the basis of systematic looting of budget surplus funds not being used to finance current expenditures.

As a result of a violent and unstable security situation, poor infrastructure, failure to update laws related to external investment, and significant under-development in the electricity and transportation sectors, private economic activity has not developed. Iraq’s labour market has remained constrained and unable to absorb the new demand, especially in a youth-rich society in which more than half a million citizens enter the job market annually.(4) Those in power have utilised state employment as a way to reduce unemployment levels, a policy that has increased the number of public sector employees from about 800,000 in 2003 to more than four million currently. Pensions for more than 1.5 million former civil servants can also be added to the civil service wage bill, as well as the salaries for thousands of volunteers in the Popular Mobilisation Forces (PMF). Despite statistics which indicate that the average Iraqi state employee’s productivity does not exceed seventeen minutes a day, those able to obtain a permanent government job enjoy stable salaries and “jobs for life” until retirement; thus, the state sector has become a significant force seeking to maintain its privileges and resisting any infringement of its rights.(5)

Although the 2015 financial budget of approximately 105 billion US dollars has already been approved, with some emphasis on austerity policies and cost control,(6) an increase in military expenditures due to the war with the Islamic State (IS or Daesh), as well as the ongoing decline in oil prices, are directly affecting the state's ability to satisfy the needs and demands of the Iraqi people. In response to these problems, the government has introduced new tax policies, which transfer a significant part of the burden onto the shoulders of the citizenry. More importantly, there has been no significant change in the behaviour and spending patterns of the elite. A large administration comprising more than thirty members was formed, including three vice presidents, with new institutions created as a political compromise. However, this expansion has not reduced the massive and costly privileges afforded to government officials and ministers.

Upon entering parliament, government figures and provincial council leaders have become accustomed to wealth and social prestige, adding to ordinary citizens’ feelings that government officials are serving their personal interests more than anything else. These public grievances are further fuelled by continuing poor services and high youth unemployment levels – estimated at thirty per cent prior to the economic crisis,(7) and likely to increase with declining recruitment rates in government institutions, the possible demobilisation of government contractors and the lack of security and stability.

Rising factors of social discontent

Daesh’s takeover of Mosul and a number of other cities in Iraq has also had a significant psychological impact, particularly given the Iraqi army’s failure to defeat the militia despite US pending totalling approximately 25 billion dollars on the army’s formation and training.(8) This development revealed not only the Iraqi administration’s political deficiencies, but the corruption that has permeated the army in a profound way. This corruption was exemplified by the disbursement of monthly salaries to more than 50,000 non-existent troops. This revelation prompted the Shiite authority to issue a fatwa (an advisory religious ruling) titled the “Self-Sufficiency Jihad”, which contributed to the formation of a parallel military force of militias and volunteers to support, and sometimes to replace, official government forces in the fight against IS. This development has deepened the gap between the Iraqi street and the ruling elites, who are now widely considered to be useless and even an ineffectual drain on Iraq’s resources without the ability to defend the country’s citizens or improve public services. This in turn has led to informal militias wielding greater influence in the country.

The country’s electricity crisis has further intensified public resentment, with electricity not available to Iraqis for more than twelve hours a day, despite searing daytime temperatures exceeding fifty degrees Celsius. The resulting widespread discontent and anger towards the political class was the spark that ignited recent protests in the city of Basra, which, despite housing Iraq’s only port and being the country’s richest city in terms of natural resources, is characterised by low levels of socio-economic development and poor quality of life for ordinary residents.

On 16 July 2015, clashes between police and demonstrators led to the death of one young man, with two others wounded.(9) The protests then spread to other cities before reaching Tahrir Square in the country’s capital, Baghdad, on 31 July, a demonstration originating from calls by media workers and activists on Facebook. The protests continued to gain momentum, and by 7 August, the numbers of participants had increased and the protesters’ rhetoric had escalated to the extent that the country’s leadership became concerned, especially after the top Shia religious leader in Kerbala recognised the protesters’ demands in a speech delivered by his representative Mr. Ahmad Safi. In the speech, Safi called for Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi to establish a genuine plan for reform to address corruption and “to be more daring and courageous in his steps towards reform, and to not be content with the secondary decisions and actions that he announced recently. He [al-Abadi] has yet to issue an important decision and [to introduce] strict procedures to combat corruption and achieve social justice”.(10)

Hours after the statement from the supreme religious authority’s representative, Abadi declared his compliance with all of the recommendations and his intention to initiate a reform plan, demonstrated by his release of the first package of reforms on 9 August.(11) These reforms included the abolition of a number of senior but non-essential government posts responsible for vast public expenditure. Among these were the country’s three Vice-Presidents, positions held by prominent Iraqi politicians Nouri al-Maliki, Iyad Allawi and Osama al-Nujaifi. Other posts eliminated under these reforms were those of the Deputy Prime Ministers. This led to the removal of the controversial Sadrist politician Baha al-Araji, the Sunni politician Saleh al-Mutlaq (who was charged with corruption concerning his poor management of funds allocated for people displaced from Sunni-majority cities) and the Kurdish politician Rowsch Nuri Shaways. The reform package also included a comprehensive and immediate reduction in the number of private security details provided for all senior officials, the elimination of partisan and sectarian quotas in determining the leadership of independent bodies, a reduction in the number of ministries and the formation of an anti-corruption council to be headed by the prime minister.

Under increasing pressure from the mass protests and calls from the supreme religious authority, in addition to the Sadrist movement leader’s threats to support the protests if the reforms were not implemented, the Iraqi parliament unanimously approved the reforms on 11 August. Moreover, the Iraqi Council of Representatives has announced a series of reforms emphasising the ending of proxy appointments for senior officials and the implementation of professional recruitment criteria for government bodies to replace the system of appointing officials on the basis of party loyalties and affiliations. Other reforms introduced included legislation requiring government officials with dual citizenship to abandon their non-Iraqi nationalities, and the introduction of regulations punishing those representatives who fail to attend parliamentary sessions without providing reasonable justification.(12)

It is still too soon to guarantee the implementation of these reforms, especially since most of them require legislation that may take time for discussion and will perhaps lead to compromises among the political blocs. This uncertainty also extends to leadership figures’ verbal promises, issued to quell public anger and respond to the supreme religious authority’s demands. These doubts have raised many questions marks over the possibility of implementing the reforms and over the extent to which Abadi will be able to change the nature of the existing system and the quota structure without negatively affecting the domestic and regional political balance.

On 16 August, Abadi issued a second package of reforms reducing the number of ministerial staff, cutting the number of cabinet members from thirty-three ministers to twenty-two. Abadi also abolished four ministries and merged another four. It appears that the second package of reforms has been issued as a Diwani order, which means it is immediately effective on the date of issue, despite amounting to ministerial changes that are supposed to be voted on by the parliament.

Shia-Shia dispute

Internal Shia conflict is of crucial importance in this context, as the protests have to date been limited to Shia-dominated cities. In some respects, this internal conflict represents a kind of challenge between the Shia general public and the Shia Islamic elite which has led Iraq’s political scene since 2003. Most of Iraq’s Sunni-dominated cities, meanwhile, are either under IS control or experiencing armed conflict between the IS and Iraqi forces, meaning they are largely uninvolved in Baghdad’s course of events. Elsewhere in the country, the Kurdistan region is focused on its own problematic issues concerning the extension of its president Masoud Barzani's term, the need for constitutional changes to allow such an extension and bargaining with other powers regarding the form of the region's constitution. Although there are some similarities between the bipartisan consensus in Baghdad and Erbil, and the various forms of corruption and clientelism, the Kurdish public’s focus on that region’s own problems distance it from the concerns of the Shia public.

This in turn raises an important question about the extent to which reforms can be implemented without breaching the existing consensus on the elitist bargain between Shia, Kurd and Sunni leaders, because the reforms will involve the federal government in response to Shia public pressure. Many Kurdish representatives and officials have asserted that any changes should not affect the existing balance between the country’s constituent groups, imposing major constraints on Abadi's ability to implement any significant reforms for the Shia public and limiting his scope so as not to threaten the representatives of the constituent elements. Furthermore, in these circumstances, any direct clash with the existing political consensus may threaten the country’s unity, especially given Baghdad's limited ability to control or impose its laws upon the Kurdistan region and Sunni-dominated areas. Herein lies the paradox: despite playing the most significant role in reproducing political and social schisms in Iraq, the existing system of political consensus seems to be the only way to maintain Iraq as a united political entity.

In addition to the above, another question is how the relationship of these protests, or their future form in the event of their escalation, will affect internal Shia rivalries. Since IS took control of Mosul, shifting Shia rivalries have emerged among the Shia population generally with regard to fighting the group and supporting the Popular Mobilisation Forces (PMF). The PMF is a large umbrella organisation encompassing several militias and groups, with these various constituent bodies having differing political aspirations and ideological perceptions of Iraq and its post-IS regional role. Those PMF militias affiliated to the Iranian regime and reflecting its revolutionary ideology, such as the Badr Organisation, Asaib al-Haq (the League of the Righteous), and the Hezbollah Battalions, see themselves as an integral part of the regional axis led by Iran, which has adopted some radical and anti-western ideas. Meanwhile, other groups in the PMF, those connected to Shia religious authorities or parties led by Shia families, such as the Sadrist Movement and the Islamic Supreme Council of Iraq (ISCI), favour a reduction in radicalism while maintaining the existing Shia balance of power.

The competition between adherents of these two ideological poles takes the form of open conflict, with the first, Tehran-affiliated bloc seeking to improve its position within the balance of power by relying on Iranian military support and the popular role it plays among the public. This bloc temporarily aligned itself with Nouri al-Maliki, the former prime minister, who included the Badr Organisation in his coalition during the last election. The other bloc, meanwhile, seeks to maintain its power and influence in Shia areas by relying on Iraq’s Shia religious authority – not only because this represents the sole guarantor of the Shia balance of power, but also because it maintains political independence from Iran.

Based on this reality, the recent actions of Asaib al-Haq can be understood as an organised attempt to exploit the street protests and to embrace the call to transform Iraq from a parliamentary system to a presidential one, as it is believed that such a system would ensure Shia majority rule and concentrate more power in the hands of Shia forces. This action partially meets the protesters' demands to renounce and end the quota system, which has created an inconsistent and ineffective government, and a feudal and partisan system. However, this partial concession does not mean agreement with the protesters’ goals, with many civil activists and secularists warning of the potential dangers of allowing these groups to control the demonstrations and divert them from their primary objectives. Thus, protesters at recent demonstrations have focused on emphasising different agendas and approaches and avoided giving any priority to demands of a group like Asaib al-Haq, which is far from representing the Shia street.

It seems that the leader of the Sadrist Movement, Muqtada al-Sadr, who recently broke with the leaders of Asaib al-Haq, has sensed the threat posed by the organisation and similar groups to use the demonstrations to pursue their own agendas. In light of this realisation, al-Sadr has enthusiastically adopted the idea of government reform, to the extent of threatening to call on his supporters to hold large-scale demonstrations if the parliament refuses to implement the first reform package proposed by Abadi; this is despite the fact that this reform package has eliminated one of the Sadrist movement’s most prominent political figures, Baha al-Araji.(13)

These factors have raised an important question concerning the way in which Abadi has formulated his reform project. It may seem, at first glance, that he has been placed in an uncomfortable position due to coming under pressure from the Shia public and being compelled to enter into confrontations with strong opponents. On closer examination, however, the demonstrations and the Shia religious authority’s adoption of some of the protesters’ demands have given Abadi a great opportunity to introduce political and administrative changes that may allow him to work more comfortably. In addition to this, his elimination of Nouri al-Maliki from the Vice-President’s post seems to be the most personally advantageous result of the reforms in a direct sense, as it may lead to a final split between groups of Abadi and Maliki supporters in the Islamic Dawa Party. This lends credibility to the claims of Maliki's allies that Abadi is taking advantage of the atmosphere created by the protests and of his mandate from the religious authorities to get rid of his Shia rivals.

Most likely, this issue will deepen the split and Abadi will benefit from relying more heavily on his alliance with the supreme religious authority, which remains the strongest party in the Shia political equation. Despite the religious authority’s efforts to avoid direct intervention in daily political life, it will support Abadi, at least implicitly, because its primary objective is to reform the existing system and to prevent its collapse, which would create a significant power vacuum and allow radical forces and armed militias to strengthen their influence.

Possible trends

Abadi’s reform package has been received with supportive public rallies, and the fact parliament passed the package created an optimistic atmosphere. However, there are lingering concerns that it may weaken the protests’ momentum, especially since most of the approved sections will take time to be passed into law. Since it’s reasonable to believe that the political class may back out of some of these reforms, or suspend their implementation once the momentum of the protests dies down, as has happened on previous occasions, the protesters’ ability to maintain the momentum of the demonstrations is of critical importance in realising the promise of reform in the country.

If the biggest challenge facing the protesters is to continue pressuring Iraq’s political class, then Abadi’s greatest challenge will be his ability to exploit public pressure in order to implement substantive reforms on critical issues. At the same time, Abadi must ensure that no political powers fear a coup because they feel he has reduced some of their power. Thus far, Abadi seems to be making cautious progress with his own inner circle among his partisan bloc. At the same time, other political powers are monitoring him in order to ensure that any concessions will not shift the balance in favour of Abadi or his party.

Abadi's willingness and ability to implement these radical reforms can be measured in three ways: the nature of the future reforms he has promised, the names put forward for governmental positions and how he handles corruption issues, particularly those involving senior officials.

The second reform package includes measures to reduce government staff and ministries. Regardless of how Abadi works to implement these reforms without disturbing the fundamental balance of power among the major parties, until now the parties most affected by the decision to reduce the number of ministries are minorities such as Turkmen and Christians. No major party will be prepared to support reforms that may affect it more than others, which means that Abadi will be in the position of choosing between managing the reform process through coordinating with the other parties - a difficult and slow process - and implementing the reforms without consulting these parties. Choosing the latter option would expose him to personal or political retaliation, a potential source of further destabilisation of the country’s already shaky political stability, especially if the conflict moves to the street and actors resort to non-political tactics.

On the issue of appointing new administration officials, Abadi has yet to announce any new appointments. Protestors are demanding that technocrats be selected to fill the vacant positions which Abadi introduced in his first reform package. However, the blurred concept of “technocrats”, Abadi's continuous recourse to those politicians closest to him to tackle the corruption issue and the constitutional requirement of parliamentary approval on any appointees will complicate the replacement process and may lead to further institutional paralysis.

On the subject of corruption, Abadi promised to form a supreme council for addressing the issue, and to bring charges against those accused of involvement in corruption. While the former prime minister Maliki vowed similar action, most of the time his threats were directed at his political rivals. There are two questions now that Abadi has made his promises: will he be able to make progress on this issue, even if such charges are levelled at his close friends or even his own party leaders, such as Maliki? And second, does Abadi have the tools to issue arrest warrants, and is there an independent judiciary to do so?

The release of Abadi’s second reform package coincided with the release of the second Parliamentary Commission of Inquiry on the fall of Mosul. This report holds former Prime Minister Maliki and a number of military commanders responsible for the fall of Iraq’s second largest city, and recommends referring them all for trial. Yet, it is still unclear what action may ensue from this report’s release. Maliki pre-empted the report’s announcement to travel to Iran for an “official” meeting, although he is theoretically no longer a vice president. In Iran, he received a warm welcome, not only indicating that Iran will stand by him, but also suggesting an escalation of intra–Shia polarisation between groups close to the Tehran government, for whom Maliki seems to be a political representative, and the Iraqi parties damaged by Maliki’s presidential term (ISCI and the Sadrist Movement), backed by the Najaf authority. Most likely, Abadi is trying to strike a balance between the two camps instead of aligning absolutely with one of them; however, the escalation of this polarisation may eventually force him to choose one side over the other.

Ultimately, if there is agreement that three hundred billion US dollars were wasted during the previous government’s term, then opening effective corruption cases against those responsible means calling into question the accountability of Iraq’s entire political class and the political regime that governed the country throughout the past three years. It was not expected that Abadi would enter this fray, both due to his personal affiliation to this political class and to the ongoing military action against the Islamic State. Thus far, the whole Iraqi political process has been grounded on the leadership’s immunity, and collision with any of these leaders may mean the collapse of the whole process, creating a vacuum in which Abadi will likely be sacrificed.

_________________________________________

Copyright © 2015 Al Jazeera Centre for Studies, All rights reserved.

*Harith al-Hasan is an Iraqi researcher and analyst.

References

1. Frank R. Gutner, Political Economy of Iraq: Restoring Balance in a Post-Conflict Society, (UK: Edwards Elgar Publishing, 2013).

2. Arend Lijphart, “Consociational Democracy”, World Politics 21 (1969): 207–225; and Arend Lijphart, “Constitutional Design for Divided Societies”, Journal of Democracy 15 (2004): 96-109.

3. Mazhar Mohammed Salah's session of the governmental budget (2015)

4. Frank R. Gutner, “The Political Economy of Iraq”, (2015), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jHVSpYB2UwU .

5. Mazhar Mohammed Salah's session of the governmental budget (2015).

6. Saif Hameed, “Iraq Adopts Revised 2015 Budget Curbed by Low Oil Prices”, Reuters, 29 January 2015, http://www.reuters.com/article/2015/01/29/iraq-budget-idUSL6N0V86ML20150129.

7. Mazhar Mohammed Salah's session of the governmental budget (2015)

8. Michael Knights, “The Long Haul: Rebooting US Security Cooperation in Iraq”, Washington Institute for Near East Policy (2015), http://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/view/the-long-haul-rebooting-u.s.-security-cooperation-in-iraq.

9. Al-Sumaria, “Basra Security Committee: Two Protestors Dead, Two Others Injured During Protest in Province’s North”, 17 July 2015.

10. Al-Safir, “Al-Sistani Demands al-Abadi to Fight Corruption”, 7 August 2015.

11. Website of Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi, “The First Package of Reforms to the Council of Ministers”, 9 August 2015, http://www.pmo.iq/press2015/9-8-201503.htm.

12. Al-Sumaria, “Representatives Reform Paper”, 10 August 2015, http://www.alsumaria.tv/mobile/news/142845/السومرية-نيوز-تنشر-ورقة-الإصلاح-النيابية/ar.

13. Al-Baghdadia, “Al-Sadr Threatens Demonstrations in Front of Parliament if Reform Package Not Approved”, 9 August 2015.