The education policy of the Justice and Development Party (in Turkish, Adalet ve Kalk?nma Partisi - AKP) under the leadership of Recep Tayyip Erdo?an in Turkey has increasingly been a topic of debate among international observers. The recent interest is due to the rise in the number of imam-hatip(1) (‘religious’) schools after the new education law (known as 4 4 4) was introduced by the Parliament in 2012. The rise of imam-hatip schools has been perceived as Islamization of Turkey’s secular education system. This report argues that the rise in the number of the imam-hatip schools is a simple manifestation of pluralisation of Turkish education system—which had long been regarded as mono-cultural and accordingly insensitive towards demands by a measurable segment of society for religious schooling. For the first time in Turkey’s history, the AKP introduced elective Kurdish courses into the middle schools in 2012, passed legislation in 2013 to allow establishing private schools in Kurdish, and abolished the mandatory “National Security Course” given by military officers in high schools as well as mandatory oath-taking ceremony in elementary schools. Conversion of general high schools into imam-hatip schools is a small part of a wide-ranging conversion of general high schools into academic Anatolian, vocational as well as imam-hatip schools—which started in 2010, long before Erdo?an’s speech on raising “religious youth” in 2012.

Introduction

Imam-hatip schools —which aim to provide religious as well as general education— have always been a controversial issue between the conservative (i.e. the religious) and secularist segments of Turkish society. They have increasingly been featured in local and global discussion. One reason for this interest is the linkage made between the rise in the number of imam-hatip schools in recent years and Turkey’s President Recep Tayyip Erdo?an. Erdo?an has repeatedly been criticized as being populist and authoritarian by his opponents in the recent years. An article by Christie-Miller of Newsweek pretty much summarises the change in how some international observers and analysts see Erdo?an from his early career as Prime Minister to the present:

“In its early years, Erdo?an and AKP forged a reputation as reformists, passing EU-inspired legislation, and subduing Turkey's once-meddlesome military, seemingly to create a more liberal, pluralist society. More recently, however, Erdo?an – who ascended from prime minister to president in elections in August [2014] and enjoys a level of authority comparable only to that of Turkey's founder, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk – has spoken more openly of his desire to recast the country along conservative lines.”(2)

While some conservatives in Turkey accept imam-hatip schools as an instrument of religious education, other conservatives reject them for being a state instrument for shaping religion. The secularist community in Turkey, on the other hand, has long regarded imam-hatips as a threat to Turkey’s secularist system.(3) Recently, however, critics add that parental choice is being denied as part of a move by the government to convert secular institutions into imam-hatip schools.(4)

Writing for Foreign Affairs, Ackerman and Calisir claimed that: “In Turkey, where there has been a rise in Islamic religiosity, President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, founder of the pro-Islamist Development and Justice Party (AKP), is converting some public schools into seminaries called imam–hatips (or traditional training schools for Sunni Muslim clergy) in an effort to raise a generation of ‘religious youth.’”(5) Similarly, citing that 1,447 general high schools were converted into imam-hatip schools during 2011-14, one Turkish columnist of Al-Monitor, Kadri Gürsel, has argued that the ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP) has been shaping the education system according to “the Sunni faith” and accordingly Islamize the education system to raise a “devout youth.”(6)

Before discussing why there is an increase in the number of imam-hatip schools and what that means for Turkey’s education system, I present some facts about the ongoing conversion of general high schools into imam-hatips.

Conversion of General High Schools

Contrary to what has been cited, 1,447 general high schools have never been converted into imam-hatip schools during 2011-14. According to official data obtained from the Ministry of National Education, between 2011-2014, only a total of 82 general high schools were converted into imam-hatips (Table 1). One can see the huge difference between 1,447 and 82.

Table 1. The number of vocational and imam-hatip high schools that are converted from general high schools (2010-2015).

|

Year |

Vocational high schools |

Imam-hatip high schools |

|

2010 |

66 |

5 |

|

2011 |

15 |

2 |

|

2012 |

120 |

23 |

|

2013 |

377 |

48 |

|

2014 |

1 |

9 |

|

2015 |

3 |

4 |

Source: Data obtained from the Ministry of National Education

I should also add that conversions of general highs schools into imam-hatips did not occur out of vacuum; nor that came out as part of Erdo?an’s will to “raise a devout youth” as expressed in one of his statements in 2012. Rather, the Ministry of National Education decided in 2010 to close all general high schools in order to increase the quality of education as well as stream students into either more academic (Anatolian) or vocational types of high schools.(7)

The main reason for this change was to lessen the burden of centralised high school entrance exam on families and to decrease the stress of students. Whether closing all general high schools was a good policy or not has been a hotly debated topic. I also wrote a commentary in June 2010 to warn that such a move might increase the competition among middle school students to be admitted into a “top” high school.(8) Nonetheless, the Ministry of National Education has decisively closed down all general high schools. Accordingly, all general high schools have been converted into either more academic (such as Anatolian high schools) or vocational high schools as well as imam-hatips starting from 2010. Based on official data for the 2011-2014 period, while only 82 general high schools were converted into imam-hatips, 513 general high schools were converted into vocational high schools (Table 1). In other words, the number of converted vocational high schools is much higher than the number of those converted imam-hatip high schools.

What are Imam-Hatip Schools?

Contrary to what Ackerman and Calisir have presented, imam-hatips are not (private) seminaries or “traditional training schools for Sunni Muslim clergy.” According to its constitution, Turkey is a secular state. Moreover, according to Turkish laws and regulations, all imam-hatips in Turkey are public schools. In other words, all imam-hatips are strictly overseen and inspected by the state. Just like any other public schools in Turkey, the Ministry of National Education decides the curricula, prepares textbooks, and appoints teachers and administrators of imam-hatip schools. Imam-hatips are neither traditional training schools nor madrasas. Imam-hatip high schools are public schools that officially aim to provide preparatory training for religious staff including imams and hatips (orators/preachers) as well as general education for higher education. One should also note that the demand for these schools cannot be explained by their orientation toward preparatory training for imams and hatips. Rather, most people send their children to these schools to get a modern education as well as a general training in religious studies. They also have been very instrumental in increasing girls’ participation in education.

Interestingly, the existing regulations ban private imam-hatips. In short, all religious education in private and public schools in Turkey are strictly controlled by the state. Moreover, after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, imam-hatip schools in Turkey have been considered as the most notable model for Islamic countries. They were lauded as an alternative model to madrasas.(9) The success of this model lies in its integration of religious courses with (secular) general education. To illustrate, imam-hatips students take all courses taught in general high schools (i.e., Turkish, English, mathematics, science, history, geography, philosophy, etc.) plus some courses related to Islamic history, Islamic law, Arabic and Quran. Moreover, peaceful aspects of the Islamic faith, as opposed to extremism, are being stressed and an Islamic understanding based on modern science is being taught.

Education Policy During the AKP’s Rule

In Turkey’s education system, not only minority Alevis and Kurds but also majority Sunni Turks have been unsuccessful to get their demands represented in schooling. Alevis have been unhappy with the mandatory course of “the Culture on Religion and Moral Knowledge.” Kurds have been lobbying for schools and courses in Kurdish. Sunni Turks have been demanding more courses on religion and/or imam-hatips. For many years, Kurds, other minorities as well as some intellectuals have objected to the oath-taking ceremony in primary schools with no result. The oath has clear nationalist wording such as “I offer my existence to the Turk[ish] existence as a gift” and as such had been the subject of a severe criticism from various intellectuals and non-Turk citizens.

The AKP has been a leading voice in the drive towards reform with a particular emphasis on education.(10) In fact, Turkey has during AKP rule achieved unprecedented success in increasing access to education from preschool level to higher education. According to OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), Turkey improved its overall performance by 20 points between 2003 and 2009. The World Bank stated that Turkey’s rapid progress in PISA reflected both Turkey’s strong economic performance as well as decisive reforms.(11) While more budget was allocated to military than education before, AKP prioritized spending on education. Education funding has increased from 2.84 percent of total GDP when the AKP rose to power in 2002 to 3.99 percent in 2013. Turkey’s persistent participation in international assessments such as PISA and TIMSS as well as joint educational projects with the international organization such as the World Bank, UNICEF, European Commission, and Council of Europe shows that AKP is not isolationist. In other words, the AKP has a comprehensive and internationalist outlook, as opposed to an ideological and nationalistic outlook of its predecessors, in its education policy.

The AKP’s rule can be described as a period of pluralisation of education.(12) For the first time in Turkey’s history, elective Kurdish courses were introduced into the middle schools in 2012 and legislation was passed in 2013 to allow establishing private schools in Kurdish. Furthermore, the AKP abolished mandatory “National Security Course” given by military officers in high schools. Moreover, as part of the “Democratisation Package” announced by Erdo?an on September 30, 2013, the national oath-taking ceremony in primary schools was abolished.(13) He criticised forcing female students to take off their headscarves, a terrible and undemocratic practice ended thanks to AKP intervention. At the same time, as a conservative leader, Erdo?an gave special importance to policies that prevent drug addiction among students and encouraged them to learn national and spiritual values. He also stressed that devout youth are tolerant of different opinions and faiths. Even when he talked about raising religious youth, he also clearly talked against brainwashing students or their indoctrination.(14)

One should also note that while there existed a few cases in which students were provisionally placed into imam-hatip high schools due to technical problems in 2013, no student has been placed into imam-hatips forcibly. There is nothing wrong in making imam-hatips available to the people as long as there is a demand for such schools. To understand the growing demand for imam-hatips more clearly, one has to contextualise the nature of transformation in Turkey in the last two decades.

On February 28, 1997, Turkish military issued a memorandum that forced the pro-Islamic Prime Minister Necmettin Erbakan to resign. The military memorandum included many items that were directly related to education. Among the most important ones was the order to shut down imam-hatip middle schools. Despite strong demand for these schools for years due to wide support for religious education, and the preference by many families to send their daughters to these schools only, the coalition government formed after Erbakan implemented the military decree to shut them down.(15) Again following the lead of the military, the Board of Higher Education (or YÖK in Turkish) under the same coalition also discriminatorily changed the rules for admission to universities. As a result, it became almost impossible for the graduates of imam-hatip high schools to enter into selective higher education programs. Both the closure of imam-hatip middle schools and changes in the admission process made imam-hatip schools less attractive. Thus, while the total number of high school students continued to rise, the number of imam-hatip students dropped sharply after the military memorandum of 1997 (Table 2).

Table 2. The number of imam-hatip high school students as well as total number of high school students (1995-2014).

|

Year |

The number of imam-hatip high school students |

Total number of high school students |

|

1995 |

186,688 |

1,716,143 |

|

1996 |

192,727 |

2,072,698 |

|

1997 |

178,046 |

2,065,168 |

|

1998 |

192,786 |

2,013,152 |

|

1999 |

134,224 |

2,019,501 |

|

2000 |

91,620 |

2,128,819 |

|

2001 |

71,742 |

2,316,832 |

|

2002 |

64,534 |

2,435,586 |

|

2003 |

84,898 |

3,587,436 |

|

2004 |

73,563 |

3,039,449 |

|

2005 |

108,064 |

3,258,254 |

|

2006 |

120,668 |

3,386,717 |

|

2007 |

129,274 |

3,245,322 |

|

2008 |

143,637 |

3,837,164 |

|

2009 |

198,581 |

4,240,139 |

|

2010 |

235,639 |

4,748,610 |

|

2011 |

268,245 |

4,756,286 |

|

2012 |

380,771 |

4,995,623 |

|

2013 |

474,096 |

5,420,178 |

|

2014 |

546,443 |

5,691,071 |

Source: Data obtained from the Ministry of National Education statistics

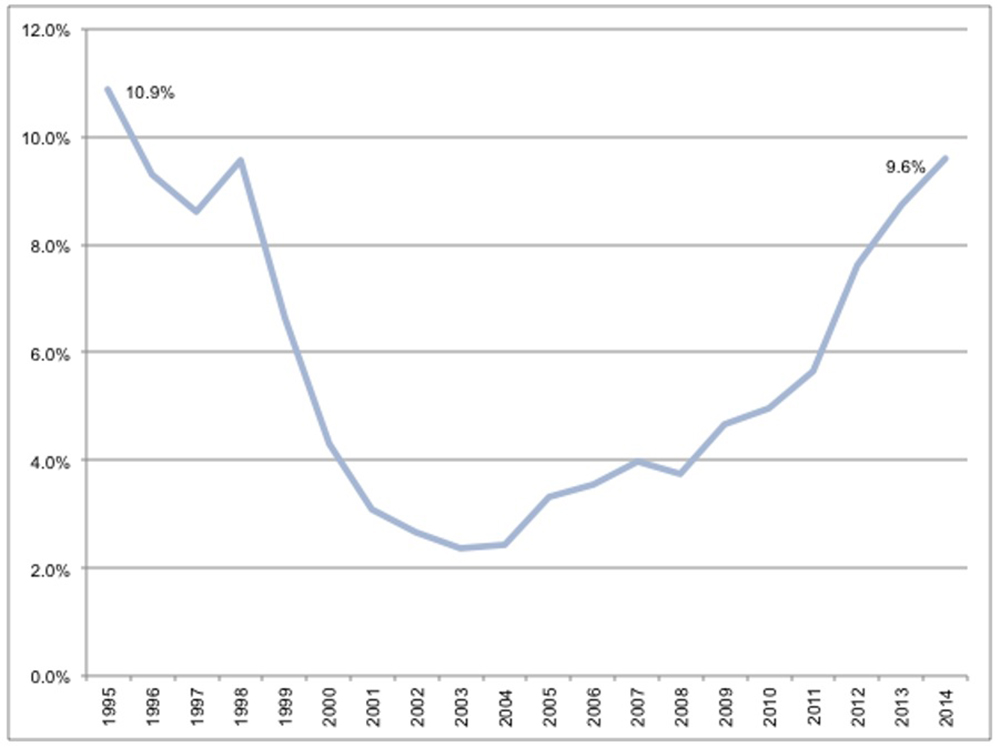

As indicated in the Figure 1, after the military intervention, share of the imam-hatip high school students in the total number of high schools students sharply dropped from 10.9% in 1995 to almost 2% in 2002, the year the AKP came into power. After AKP’s advent to power, the number of imam-hatip high schools again started to rise gradually (Table 1) and the share of imam-hatip high school students rose back to 9.6% as of 2014 (Figure 1). In other words, even after the AKP’s decade-long rule, the percentage of imam-hatip high school students has not reached pre-1997 military intervention levels. As long as there is no artificial intervention or barrier against access to imam-hatips, it is likely that the share of imam-hatip schools will continue to increase in the coming years. Similarly, after the opening of imam-hatip middle schools in 2012, their number has rapidly risen to 1,655 as of 2015. It is important to keep in mind the fact that some 600 imam-hatip middle schools were shut down overnight, not by the will of people but due to the military memorandum of 1997, and thus there would be more such schools as long as parents freely chose to send their children to these schools.

Figure 1. The proportion of imam-hatip high school students in the total number of high school students (1995-2014).

|

| Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan has presided over a package of contentious education reforms, pushing for religious Imam Hatip-style schools [AFP]Source: Data obtained from the Ministry of National Education statistics |

Conclusion

Some changes and initiatives in recent years (such as introducing elective religion courses into middle/high schools and conversion of general high schools into imam-hatip high schools) are perceived as Islamisation of Turkey’s secular education system. However, in order to understand the rise in the number of imam-hatip schools, one should contextualise the current education policies and practices by placing them within the wider Turkish drive for pluralisation in the last decades. As I have argued in this paper, conversion of general high schools into imam-hatip schools is a small part of a wide-ranging conversion of general high schools into academic Anatolian, vocational as well as imam-hatip schools—which started in 2010. Turkey has heavily invested in education and access to education for both girls and boys from pre-school to higher education has sharply been increased in the last decade during the AKP era. It is plausible to claim that the AKP under Erdo?an leadership has been the greatest promoter of education from pre-school to higher education for both girls and boys in Turkey. Moreover, Turkish education system offered elective Kurdish and religion courses, allowed private Kurdish schools, abolished nationalist oath taking ceremony in elementary schools, abolished mandatory “National Security Course” given by military officers in high schools, lifted the ban on wearing headscarf in universities in the last decade. In other words, education in Turkey, which had been regarded as “mono-cultural,” has become more diversified, accommodating popular demands for more choice during the AKP’s rule. Still, there are unmet demands from various social groups in Turkey. For instance, some Alevis oppose mandatory religion courses and demand a constitutional change for this purpose. Moreover, the current constitution and regulations related to education still dictate indoctrination of Kemalist ideology, i.e., Mustafa Kemal Atatürk is the single “father” and “savior” of the Turkish “military-nation.” Most liberals and conservatives demand an end to such indoctrination. All such demands show that Turkey needs further pluralisation of its education system.

(1) ?mam Hatip is a compound name: the word imam refers to a religious leader, including one who leads prayer; the term ‘hatip’ originates from the Arabic word 'khatib': he who delivers the Friday sermon (literally a khatib is an ‘orator/preacher’).

(2) Christie-Miller, Alexander. “Erdogan Launches Sunni Islamist Revival in Turkish Schools.” Newsweek, December 16, 2014. http://europe.newsweek.com/erdogan-launches-sunni-islamist-revival-turkish-schools-292237 [retrieved: 19/02/2016]

(3) A?lamac?, ?brahim, and Recep Kaymakcan. “A Model for Islamic Education from Turkey: The Imam-Hatip Schools.” British Journal of Religious Education, to appear.

(4) Letsch, Constanze. “Turkish Parents Complain of Push towards Religious Schools.” The Guardian, February 12, 2015, sec. World news. http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/feb/12/turkish-parents-steered-religious-schools-secular-imam-hatip [retrieved: 25/02/2016]

(5) Ackerman, Xanthe, and Ekin Calisir. “Erdogan’s Assault on Education: The Closure of Secular Schools.” Foreign Affairs, December 23, 2015. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/turkey/2015-12-23/erdogans-assault-education [retrieved: 17/02/2016]

(6) Gürsel, Kadri. “Erdogan Islamizes Education System to Raise ‘Devout Youth.’” Al-Monitor, December 9, 2014. http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2014/12/turkey-islamize-education-religion.html [retrieved: 17/02/2016]

(7) MEB [The Ministry of National Education]. “Genel Liselerin Anadolu Liselerine Dönü?türülmesi Konulu 2010/30 Nolu Genelge.” MEB, 2010. http://ogm.meb.gov.tr/belgeler/genelge_2010_30.pdf [retrieved: 23/02/2016]

(8) Çelik, Zafer, and Bekir S. Gür. “Ortaö?retime Geçi?in Yeniden Düzenlenmesi | Yorum.” SETA Foundation, June 30, 2010. http://www.setav.org/tr/ortaogretime-gecisin-yeniden-duzenlen-mesi/yorum/690 [retrieved: 23/02/2016]

(9) A?lamac?, ?brahim, and Recep Kaymakcan. “A Model for Islamic Education from Turkey: The Imam-Hatip Schools.” British Journal of Religious Education, [forthcoming].

(10) Çelik, Zafer, and Bekir S. Gür. “Turkey’s Education Policy during the AK Party Era (2002-2013).” Insight Turkey 15, no. 4 (2013): 151–76.

(11) World Bank. “Promoting Excellence in Turkey’s Schools.” Washington, DC: The World Bank, March 1, 2013. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/2013/03/18023851/promoting-excellence-turkeys-schools [retrieved: 19/09/2013]

(12) For more discussion, see Çelik, Zafer, Sedat Gümü?, and Bekir S. Gür. “Moving Beyond a Monotype Education in Turkey: Major Reforms in the Last Decade and Challenges Ahead,” in press.

(13) On September 30, 2013, Erdo?an unveiled one of the most comprehensive liberalizing reform packages in years, proposing that headscarved women be allowed to sit in parliament and work as civil servants for the first time in history of the Turkish republic as well as making several proposals to the large Kurdish minority. See Letsch, Constanze. “Turkish PM Unveils Reforms after Summer of Protests.” The Guardian, September 30, 2013, sec. World news. http://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/sep/30/turkish-pm-erdogan-reforms [retrieved: 12/03/2016]

(14) “Erdo?an ‘Dindar Nesil’i Savundu.” Radikal, February 6, 2012. http://www.radikal.com.tr/politika/erdogan-dindar-nesili-savundu-1077899/ [retrieved: 17/02/2016]

(15) Bozan, ?rfan. Devlet ile Toplum Aras?nda (Bir Okul: ?mam Hatip Liseleri. Bir Kurum: Diyanet ??leri Ba?kanl???). Ka