The international conference “Shaping a New Balance of Power in the Middle East: Regional Actors, Global Powers, and Middle East Strategy”, co-hosted by Aljazeera Centre for Studies (AJCS) and John Hopkins University (JHU) in Washington earlier this summer, has triggered wider debate about the nature and the promise of an emerging balance of power in the region. New questions are raised about how a new balance can be different from the traditional U.S.-Soviet politics of bipolarity and rival proxies, the impact of new players, the power of militant groups and other non-state actors, and whether any emerging balance of power can be sustainable in the future. For instance, the Gulf and the Middle East are suffering a paroxysm of conflict involving virtually all the regional states as well as the US and Russia and many different non-state actors. What dynamics are driving this chaos? What can be done to contain or reverse the damage? How might a new balance of power emerge?

As part of a special series “Shaping a New Balance of Power in the Middle East”, AJCS welcomes the insights of Dr. Mark N. Katz who has examined Putin’s approach to several rivalries in the Gulf and the Middle East: 1) the Israeli-Palestinian dispute; 2) Syria’s many conflicts; 3) Iran vs. the Gulf Arabs and Israel; 4) the war against Al Qaeda and ISIS; 5) the civil wars in Iraq, Yemen, and Libya; and 6) the Qatar crisis. What this shows is that Putin’s main approach to the Gulf and the Middle East has been one of seeking good relations with all major actors (except the jihadists) despite their many differences with one another. By not definitively choosing sides between parties in dispute but being willing to cooperate with them all as Dr. Katz argues, Moscow gives all the major actors in the Gulf and the Middle East (again, except the jihadists) an incentive to cooperate with Moscow despite its simultaneous support for their adversaries. So far, Putin’s “support opposing sides simultaneously” approach has been remarkably successful, but it is also one that has inherent risks.

From when he first came to power at the turn of the century, Vladimir Putin set about rebuilding Moscow’s influence in the Middle East, which had declined sharply at the end of the Cold War and the collapse of the Soviet Union. Since then, Putin has done a remarkable job not just of rebuilding ties to governments that the Soviet Union had been close to, but also in developing good relations with traditionally pro-American ones that the USSR had had poor relations with—including Turkey, Iran, the Gulf Arab states, and Israel. But, it has been especially since the beginning of the Russian intervention in Syria in September 2015 that Russia’s role in the region has expanded. In Syria, Moscow was able to turn the tide of battle from a point when the Assad regime’s survival was in doubt in mid-2015 to now when it appears to be largely victorious. And with this Russian military success and increased diplomatic role coming at a time when the United States is seeking to limit its military involvement in the region after the painful experience of its less than successful interventions in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Libya, Russia appears to be a rising power in the Gulf and Middle East while the U.S. is a declining one.

Under Putin, Russia has pursued four broad goals in the Gulf and the Middle East: 1) make sure that no government there contributes to opposition movements in Russia’s Muslim regions (or elsewhere in the former Soviet Union) like some Gulf states in particular did in Afghanistan in the 1980s and (many in Moscow believe) in Chechnya in the 1990s; 2) make sure that Russia is an important player in the Gulf/Middle East, and not excluded from it; 3) support maintaining the status quo in the Middle East to prevent the rise of revolutionary forces there which would harm Russian interests or even Russia itself; and 4) seek trade and investment with the Gulf in particular which is profitable both for Russia as a whole and for the ruling circles around Putin in particular—something that has become especially important since the imposition of Western economic sanctions against Russia targeting the Putin elite after its annexation of Crimea in 2014. What does not seem to be a major goal for Putin is eliminating American influence in the region. While opposing U.S. policy when it has sought to alter the status quo (i.e., intervening in Iraq and Libya, and supporting the opposition to Assad), Moscow has not sought to hinder the U.S. when it supports the status quo in the region.

But just as with other external powers, Russia does not pursue its regional goals in a void. The Gulf and the wider Middle East is not a passive arena in which the interplay of external actors defines what occurs there. It is instead an area where governments and other forces in the region are actively pursuing their own, often clashing, agendas. It is in pursuit of these that regional governments and other forces have sought to either enlist active support or at least blunt opposition from various influential external powers—including Russia. The ongoing conflicts that the regional protagonists involved in have sought support of various kinds from Russia (as well as others) include the ongoing Israeli-Palestinian dispute, the civil war in Syria, the rivalries between Iran on the one hand and both its Gulf Arab and Israeli opponents on the other, the ongoing conflicts with jihadist groups such as Al Qaeda and ISIS, civil wars in other countries (Iraq, Yemen, and Libya), and most recently, the rivalry between Qatar on the one hand and Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain, and Egypt on the other.

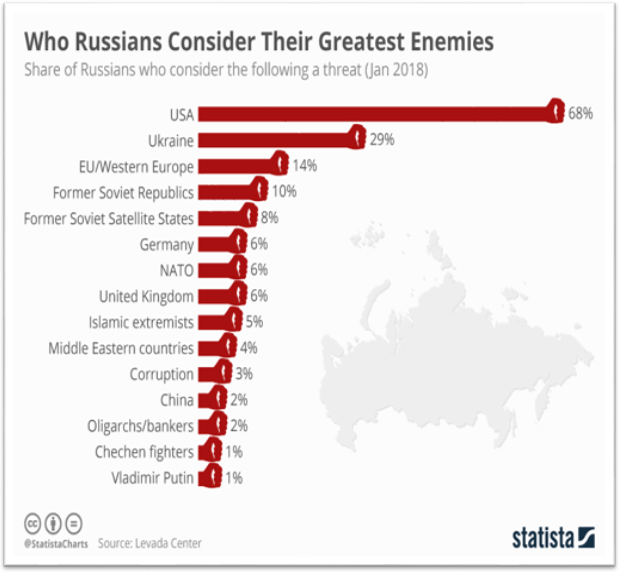

|

| Russia Enemies [Levada Center] |

Moscow did not create the many conflicts and rivalries now taking place in the Gulf and the Middle East. Moscow, though, has been able to make use of these conflicts and rivalries in order to advance its goals. But, the way it has sought to pursue its goals has not usually been through siding with one side in a conflict or rivalry against the other (the Syrian civil war is an exception), but through cooperating (or offering to cooperate) with any side (except the jihadists). Doing this can be seen as highly Machiavellian: no regional government or other force likes to see Russia cooperating with its adversary, but Moscow appears to calculate that this still gives the aggrieved partner an incentive to cooperate with it for fear that Russia will cooperate even more with its adversary otherwise. On the other hand, this approach also fits in with Putin’s relatively conservative goals of providing Gulf and Middle Eastern actors with strong incentive not to harm Russian interests (either in Russia or the Middle East), upholding the status quo, and doing business with everyone.

The fact that there is so much conflict and rivalry increases the opportunities for Moscow to cooperate with all actors (except the jihadists) in the Gulf and the Middle East—including through selling arms and providing other forms of security assistance (which would not be in such high demand if there was less conflict), and creating possibilities for Russian-sponsored conflict resolution initiatives. On the other hand, the fact that so many of Moscow’s partners in the region are at odds with one another can also pose problems for Russia if conflict among them escalates, Russian conflict resolution efforts are unsuccessful, and/or some of its partners in the region are less interested in heeding Russian advice but using Moscow to advance their own conflicting agendas. How, as well as how well, Moscow has sought to pursue its interests through maintaining some sort of balance between opposing sides shall be the focus of this paper.

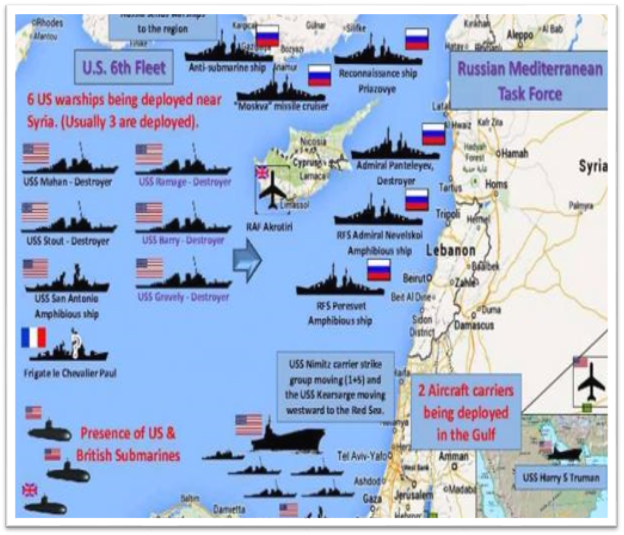

|

| Foreign Military presence in East Mediterranean [MEA] |

The Israeli-Palestinian Dispute

Just as it did during the Soviet era, Moscow has continued to express sympathy and support for the Palestinian cause under Putin. But unlike during the Soviet and Yeltsin periods, Putin has built strong relations with Israel. The two countries not only have active trade ties, but also an extensive security cooperation relationship. Further, there are strong human-to-human ties between the two countries with over a million Russian speakers living in Israel and over half a million Russian tourists a year visiting there each year. Some observers claim that there is now something akin to an alliance between Russia and Israel, or at least between Putin and Netanyahu. But while the Russian-Israeli relationship has indeed grown strong under him, Putin has been careful to continue expressing support for the Palestinian cause too. Unlike Trump who recognized Jerusalem as Israel’s capital and moved America’s embassy there, Putin set forth a plan recognizing West Jerusalem as Israel’s capital and East Jerusalem as the capital of a future Palestinian state.(1) Moscow retains close ties with Fatah, and even has good relations with Hamas. But whatever his expressions of support for the Palestinians, Putin has not given them any material support that would enable the Palestinians to seriously challenge the Israeli occupation of the West Bank or blockade of Gaza.(2) Nor does he feel any necessity to do more for the Palestinians when Arab governments themselves are not doing much for them, and some—notably Egypt, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE—are actively cooperating with Israel. With most Arab governments prioritizing the fight against their internal opponents and/or Iran over the Palestinian cause, Moscow’s close collaboration with Israel has not harmed Russian relations with Arab governments, and so is likely to continue.

Syria’s Many Conflicts

The war between the Assad regime and its internal opponents in Syria is notable because it is one case in which Moscow has not sought to balance between the two sides, but has instead decisively sided with one side against the other. Putin may have done this as a result of his fear that the Arab Spring in Syria—especially during the summer of 2015 when the Assad regime appeared about to be defeated despite Iranian support—would lead to the loss of what was then Russia’s one remaining ally in the Arab world, and that this would effectively result in Russia’s exclusion from the Middle East. Yet even though Putin has sided firmly with Assad against his opponents, Russian diplomacy has sought to engage the latter in a peace process whereby an accommodation would be made between the opposing parties (something which Assad appears to be less and less interested in as his regime’s control over more and more territory expands).(3)

Syria, though, is not just a country where an internal civil war is taking place, but also an arena in which other rivalries involving regional actors (Iran and its allies vs. Israel, and Turkey vs. the Kurds) also occurring. In these, Moscow is playing more of a balancing role. It has cooperated with Iran in defending the Assad regime, but it has turned a blind eye to Israel targeting Iran’s ally, Hezbollah, and even Iranian assets directly. Similarly, while Moscow has accommodated Turkish military intervention in northwestern Syria primarily against Syrian Kurdish forces, Moscow has also sought to persuade the Syrian Kurds that their best protection lies in making peace and joining forces with the Assad regime. What is remarkable is that, despite each party’s unhappiness that Russia cooperates with its adversary, Moscow has been largely successful in maintaining good relations with them all. Whether it will continue to be, though, is not certain—as indicated by the reportedly testy exchange between Putin and Erdogan at the July 2018 BRICS summit about Russian efforts to get the Syrian Kurds to join forces with the Assad regime,(4) and the difficulties Moscow is experiencing in tamping down Iranian-Israeli hostilities in Syria.(5)

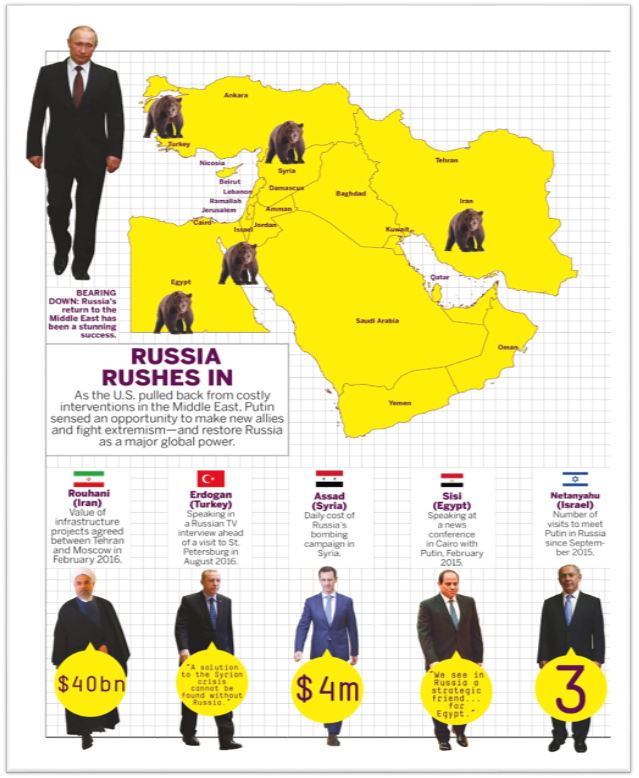

|

| Russia's return to the Middle East [Newsweek] |

Iran vs. the Gulf Arabs and Israel

Iran, of course, is not just considered a threat by Israel in Syria, but as an existential threat to the Jewish state. The Gulf Arab states—especially Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, and the UAE—also see Iran as an existential threat. For both Israel and these Gulf Arab states, the Iranian threat consists of a potential nuclear threat plus the threat from its involvement in regional conflicts. For them, US President Obama’s push for the Iranian nuclear accord was doubly threatening because they did not believe it would prevent Tehran from acquiring nuclear weapons but that the agreement could result in Washington turning a blind eye to Iranian involvement in regional conflict (fears which were based more on these governments’ insecurities about the U.S. commitment to them than on the actual threat they faced from Iran). Iran, for its part, has regarded Israel and these three Gulf Arab states in particular as hostile both by themselves and by virtue of their being U.S. allies. Unlike in Syria, where Russian support for the Assad regime puts it on the same side as Iran, Moscow has successfully pursued good relations with both Iran on the one hand and Israel and the Gulf Arabs on the other. Moscow built a nuclear reactor for Iran and has sold it sophisticated weapons as well. Moscow has long helped Tehran escape from Western economic sanctions, and now that Russia faces them itself, the two help each other do so. While the Iranians have often complained about past and present Russian behavior (especially in terms of its dealings with Tehran’s adversaries), Moscow seems to calculate that Iran has nowhere else to go, especially for security assistance.

Israel, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE, of course, do have somewhere else to go for security assistance, but Moscow’s willingness to cooperate with them is, as Putin may well have intended, an inducement for them to work with Moscow. The UAE has long been buying weapons from Russia, and in 2018 signed a “strategic partnership” agreement with Moscow.(6) Saudi Arabia is reportedly in talks to buy S-400 air defense missiles from it.(7) Israel, by contrast, is a provider of military technology (including unarmed aerial vehicles) to Russia.(8) And since 2016, Moscow and Riyadh in particular have been cooperating to limit oil production in order to bolster oil prices.(9) Despite their unhappiness about Russian cooperation with Iran, Israel and these Gulf Arab states seek two important benefits from cooperating with Russia anyway: 1) they hope to motivate the U.S., which (Trump notwithstanding) is concerned about growing Russian influence in the Middle East, to do more for them; and 2) they seek to undermine Iranian confidence in Russia as an ally. Moscow’s success in pursuing good relations both with Iran and its regional adversaries can be seen by the many visits that Israeli, Saudi, UAE, and Iranian leaders have made to Russia to meet with Putin and other top Russian leaders. Indeed, just being courted by them all helps Putin project the image of Russia as a great power.

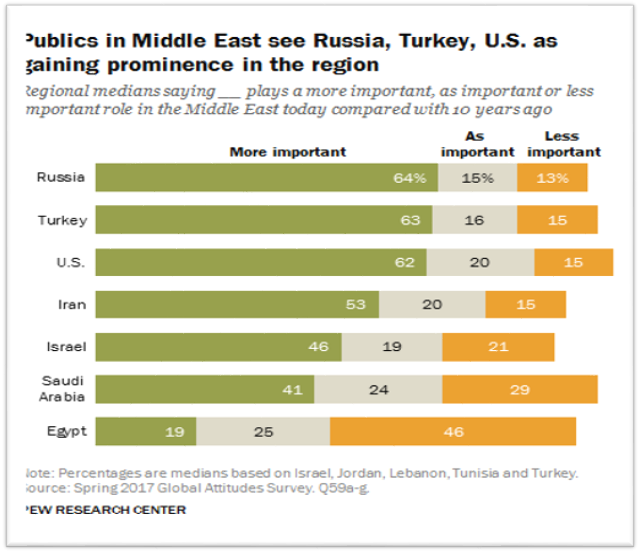

|

| Arab opinion - Russia [PEW Center] |

The War against Al Qaeda and ISIS

Moscow has frequently declared its opposition to Sunni jihadist groups such as Al Qaeda and ISIS. At his September 2015 speech to the UN General Assembly just before the beginning of Russia’s intervention in Syria, he described the Assad regime as an ally against Islamic extremism, and called upon other countries to join with them in a fight that he likened to the anti-Hitler coalition during World War II.(10) Russian foreign minister Sergei Lavrov subsequently defended Iran’s presence in Syria both because it was sanctioned by the “legitimate” Syrian government and because it was fighting against jihadists there.(11) Yet while Moscow definitely fears these Sunni jihadists—especially the ones that hale from Russia’s Muslim North Caucasus region, it has not fought as hard against them in Syria as Russian rhetoric would imply. Numerous reports about Russian military actions in Syria indicate that Russian forces, in conjunction with Syrian government and its Shi’a allies, have focused their attacks on the more moderate opposition to Assad and not on ISIS.(12) Similarly, while Moscow has decried the presence of U.S. forces in Syria, it seemed happy to let the Americans undertake more of the burden of fighting ISIS there (as well as in Iraq). Putin himself stated that he would rather fight jihadists from Russia or the Middle East “there” (i.e., Syria) rather than “here” (i.e., Russia).(13) What he did not say is that he prefers to let others do most of the fighting against them for him. While this strategy might not be admirable, so far it has proven successful.

Civil Wars: Iraq, Yemen, and Libya

While Moscow has intervened decisively on the side of the Assad regime in Syria, its policy toward the Middle East’s other civil wars has been quite different. To begin with, it has not intervened directly in any of them like it has in Syria, and does not seem eager to do so either. Instead, Moscow has worked with opposing sides in each of these civil wars—just as it has done with other conflict situations in the Middle East. In Libya, Moscow recognizes the UN-recognized Libyan government based in the west, but it also supports (along with Egypt and the UAE) the rival regime led by General Haftar in the east.(14) In Iraq, Moscow has extensive dealings with the Baghdad government (to which it has become a major arms seller), but Russia also works with the Kurdish Regional Government in the north.(15) In Yemen, Moscow recognizes the Saudi-backed Hadi government, but it also has working relations with the Iranian-backed Houthis. Moscow also maintained ties to longtime Yemeni leader Ali Abdallah Saleh (who had been forced out of office in 2012, but remained a powerful force in Yemen until he was killed by the Houthis in late 2017), and appears to still be at least talking with his successors as well as the southern secessionists (both of whom are backed by the UAE) as well.(16) This “support opposing sides simultaneously” approach to these internal conflicts, of course, resembles Moscow’s approach to the Middle East’s cross-border rivalries described above.

Qatar vs. Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain, and Egypt

Space does not permit a full discussion of what the Qatar crisis is all about, but it partly relates to a policy dispute between Doha and its critics over how best to deal with the rise of Islamism in the Sunni Arab world. Qatar sees the best way of dealing with this phenomenon as being to engage moderate Islamists in order to strengthen them vis-à-vis extremists such as Al Qaeda and ISIS, and Doha considers the Muslim Brotherhood to be moderate Islamists. By contrast, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, Bahrain, and Egypt do not consider the Muslim Brotherhood to be moderate, but extremists instead. Moscow wholeheartedly joined with Saudi Arabia and the UAE in particular in welcoming the 2013 ouster of the elected Muslim Brotherhood leader, Mohammed Morsi, as president of Egypt by General al-Sisi. But while Morsi was actually in power in 2012-13, Russia—like Qatar—had good relations with him (indeed, Putin received him in Russia a few months before his ouster and several Russian-Egyptian economic projects were announced then).(17) Putin’s policy here may simply have reflected a pragmatic desire to get along with whoever Egypt’s leader happens to be (though Moscow definitely prefers al-Sisi to Morsi).

With regard to the differences between Qatar and its Gulf Arab neighbors, Russia—like most other external powers—genuinely does not want to have to make a choice in this dispute since it regards them all as partners. Indeed, economic cooperation both with Qatar on the one hand and its Gulf adversaries on the other is highly important to Moscow, and Russia does not want to sacrifice this with either side. As with other Middle Eastern disputes, Moscow may see the “Qatar conflict” as an opportunity to derive benefits from both sides seeking its favor through various forms of cooperation. But also as with other Middle Eastern disputes, Moscow has shown that it is unwilling to curtail its relations with one side at the behest of the other, as was seen in the case of the proposed S-400 air defense missile system sales. Both Saudi Arabia and Qatar have been in discussions to buy the S-400 system from Moscow. When Saudi Arabia threatened dire consequences for Qatar if Doha bought the S-400 from Russia, Moscow made clear that its interest in selling this weapons system to Qatar remained unchanged.(18) At the same time, though, its interest in S-400s to Saudi Arabia also remains unchanged. So far, neither side in this dispute is attempting to force Moscow to make an “either/or” choice in this matter. And Moscow may hope that, like the U.S. and the West in general, it can avoid doing so indefinitely if the dispute continues.

[Video]: Russia's Energy Relations with Gulf States Panel, Jamestown Foundation, July 31m 2018

Conclusion

Putin, it must be said, has been quite successful with his “support opposing sides simultaneously” approach toward the Gulf and the Middle East. But, this approach has an inherent risk. Each opposing side in the Gulf and the Middle East would much prefer that Russia support it more and its adversaries less (or even not at all). Moscow, as noted earlier, may calculate that while opposing sides do not like Moscow also supporting their adversaries, they have little choice but to continue or even increase cooperation with Russia in order to prevent Moscow from giving even more assistance to those adversaries. But, Middle Eastern governments and opposition groups are not passive actors, and they are constantly trying to influence the foreign policies of Russia and other external actors in ways that favor them and not their adversaries.

No matter how unhappy they may be with American foreign policy, those Gulf and Middle Eastern states traditionally allied to the U.S. are not likely to give up American support against regional adversaries whom the U.S. also opposes but whom Russia supports. In other words, Russian support for anti-American actors in the region risks pro-American ones continuing or even increasing their reliance on the U.S. Thus, those states fearing Iran most—such as Israel, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE—value American support against Tehran even while they cooperate with Moscow. Further, while Moscow claims that it is in a better position than Washington to bring about conflict resolution between Iran and its adversaries because Moscow has good relations with Tehran while Washington does not, the truth is that Israel and the Gulf Arab states most fearing Iran much prefer American support against Tehran to Russian mediation with it (which they doubt would be effective anyway).

In addition, while Moscow may calculate that supporting all sides in any given rivalry may serve to keep it “in balance,” it may actually encourage an escalation of conflict that Moscow would prefer to avoid. Recently, for example, Russia’s relations with Turkey have deteriorated over Moscow’s efforts to take advantage of Syrian Kurdish vulnerability to Turkish forces in order to promote cooperation between the Assad regime and the Kurds. Similarly, Moscow’s apparent inability to prevent conflict between Israeli and Iranian (or Iranian-backed) forces in Syria risks the U.S. reinserting itself in the region by strongly aiding Israel against the common foe—and that this is something which the Gulf states which most fear Iran would welcome.

Finally, Moscow’s practice of supporting opposing sides may give at least some of them a perverse incentive: if only they can gravely weaken or even eliminate their regional adversary in a surprise attack, Moscow will not want to get involved but will adjust to the new situation. Such a scenario may turn a rivalry that is amenable to some degree of Russian management through supporting opposing sides into one that is unmanageable by Russia and perhaps anyone else. This, of course, would risk escalating disorder in the region that Moscow does not want to see.

In sum, the problem with Putin’s “support opposing sides simultaneously” approach to the Gulf and the Middle East is that while all states and most other actors (i.e., Hezbollah) may regard Russia as a partner, nobody (including Bashar al-Assad) regards it as a truly reliable ally. As a result, actors in the Gulf and the Middle East will not rely on it completely, but hedge against it instead due to its support for their adversaries.

(1) M.N. Katz, "Russia and Israel: An Improbable Friendship," in N Popescu and S. Secrieru (eds.), Russia's Return to the Middle East: Building Sandcastles?, EU ISS Chaillot Papers, 146, July 2018, pp. 103-108.

(2) D. Trenin, What Is Russia Up to in the Middle East? (Cambridge: Polity Press), 2018, p. 90.

(3) T. Miles, “U.S., France Urge Russia to 'Deliver' Assad Delegation to Syria Peace Talks,” Reuters, 6 December 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-mideast-crisis-syria-talks/u-s-france-urge-russia-to-deliver-assad-delegation-to-syria-peace-talks-idUSKBN1E01E0 (accessed 11 August 2018).

(4) K. Semenov, “Russia-Turkey Ties Face 'Moment of Truth' over Syria's Idlib,” Al-Monitor, 27 July 2018, http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2018/07/russia-turkey-syria-idlib.html#ixzz5NrGRE6QG (accessed 11 August 2018).

(5) N. Kozhanov, “As Ringmaster, Russia Runs Israel-Iran Balancing Act in Syria,” Al-Monitor, 6 August 2018, http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2018/08/russia-syria-israel-iran-golan-heights.html#ixzz5NrLqb3TS (accessed 11 August 2018).

(6) L. Sim, “Russia and the UAE Are Now Strategic Partners: What’s Next?”, LobeLog, 7 June 2018, https://lobelog.com/russia-and-the-uae-are-now-strategic-partners-whats-next/ (accessed 11 August 2018).

(7) “Russia and Saudi Arabia Hash over Details of S-400 Deliveries Deal,” TASS, 19 February 2018, http://tass.com/defense/990709 (accessed 11 August 2018).

(8) P. Hilsman, “Drone Deals Heighten Military Ties between Israel and Russia,” Middle East Eye, 3 October 2015, https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/analysis-drone-deals-highlight-military-ties-between-israel-and-russia-24061368 (accessed 11 August 2018).

(9) G. Smith, “Saudi, Russia Reaffirm OPEC Deal of Million-Barrel Oil Boost,” Bloomberg, 3 July 2018, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-07-03/saudi-russia-reaffirm-opec-deal-on-million-barrel-supply-boost (accessed 11 August 2018).

(10) “Read Putin’s U.N. General Assembly Speech,” Washington Post, 28 September 2015, https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/worldviews/wp/2015/09/28/read-putins-u-n-general-assembly-speech/?utm_term=.07a50418a4a4 (accessed 11 August 2018).

(11) M.N. Katz, “Moscow’s Balancing Act in Syria,” LobeLog, 21 November 2017, https://lobelog.com/moscows-balancing-act-in-syria/ (accessed 11 August 2018).

(12) A. Polyakova, “Putin’s True Victory in Syria Isn’t over ISIS,” Brookings Institution, 26 February 2018, https://www.brookings.edu/opinions/putins-true-victory-in-syria-isnt-over-isis/ (accessed 11 August 2018).

(13) “Better We Kill Them There than Here: Putin Explains the Merits of Fighting Jihadis in Syria,” Vesti, 8 June 2018, https://www.vesti.ru/doc.html?id=3026705&cid=4441 (accessed 11 August 2018).

(14) L. Pigman and K. Orton, “Inside Putin’s Libyan Power Play,” Foreign Policy, 14 September 2017, https://foreignpolicy.com/2017/09/14/inside-putins-libyan-power-play/ (accessed 11 August 2018).

(15) M.A. Suchkov, “Between Baghdad and Erbil: Russia’s Balancing Act in Iraq,” LSE Middle East Centre Blog, 3 May 2018, http://blogs.lse.ac.uk/mec/2018/05/03/between-baghdad-and-erbil-russias-balancing-act-in-iraq/ (accessed 11 August 2018).

(16) J. Fenton-Harvey, “Russia’s Deadly Game in Syria,” The New Arab, 6 March 2018, https://www.alaraby.co.uk/english/indepth/2018/3/6/Russias-deadly-game-in-Yemen (accessed 11 August 2018).

(17) P. Casula and M.N. Katz, “The Middle East,” in A.P. Tsygankov (ed.), Routledge Handbook of Russian Foreign Policy (London & New York: Routledge), 2018, p. 303.

(18) Russia 'To Supply S-400 System to Qatar Despite Saudi Position,” Al Jazeera, 2 June 2018, https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2018/06/russia-supply-400-system-qatar-saudi-position-180602195629315.html (accessed 11 August 2018).