The following paper is a summarized version of a keynote speech “Social Capital between State and Society: An Outside-in Refection”, delivered by Dr. Mohammed Cherkaoui at the international conference “The Quality of Political and Economic Institutions in Morocco”. The conference was hosted by the Moroccan Institute for Policy Analysis (MIPA) hosted during the 2019 Rabat Policy Forum, and focused on several related topics in three panels:

Panel 1: Trust between Democratization and Authoritarian Resilience

Speakers included Imed Daimi, “Trust Building in the Security Sector in Post-Revolutionary Tunisia”; Paola Rivetti, “Functions of Political Trust in Authoritarian Settings”; and Abass Boughalem, “Society and State: Towards a New Social Contract”

Panel 2: (Mis)Trust in State Institutions

Abdelatif Chentouf, “Reforms and their Impact on Trust in Moroccan Justice after The 2011 Constitution”; Mohammed Berraou. “Audit Anti, Corruption Bodies and the Question of Trust”; Rachid Aourraz, “How Does Institutional Trust Influence Investments?”

Afternoon lecture: Sonja Zmerli, “Political Trust in the MENA Region: Specificities and commonalities with Established Democracies”

Panel 3: Social Movements, Citizenship and Political Trust

Panelists included Kathya Berrada, “Institutional Changes: An Organic Perspective”; Anna Jacobs, “People Protest, and Parliament: Challenges and Opportunities for Empowering Democratic Institution in Morocco”; and Ingrid Heidlmayr-Chegdaly, “Political Mistrust, In-Active Citozenship and Depoliticization”

In his book “The Sociological Imagination” published in 1959, American sociologist C. Wright Mills wrote, “Neither the life of an individual nor the history of a society can be understood without understanding both.” Mills believed sociology could show us that “society – not our own foibles and failings – is responsible for many of our problems”. (1) One of the main tasks of sociology, as he would argue, is to transform personal problems into public and political issues. He expected the sociological imagination to be “the vivid awareness of the relationship between experience and the wider society.” (2)

These quotes may sound inspiring in shaping a rather multi-disciplinary approach and embracing the need for addressing both agency and structure, while probing into the detractors of the expected governance and polity in Morocco. This call for a holistic perspective can be motivating for us to move out of our academic silos, and contribute to a well-nuanced analysis of the performance of Moroccan institutions.

At the beginning of 2019, there are fresh indicators of more than one trend in the loss, or decline, of Morocco’s social capital in both political and societal dimensions. Some questions are timely and daunting: what has undermined the social capital between society and state in recent years? How has this decline moved in both vertical and horizontal directions? What indicators should one present to make such a claim without sounding alarmist or conspiratorial?

To capture the interconnectedness between Moroccans’ personal experiences, public mood, and politics, or the agency-structure connection, one needs to step beyond his/her academic comfort zones, or what our Francophone friends would call ‘spécialité’. Instead, complexity theory provides an explanatory framework for the study of “how individuals and organizations interact, relate, and evolve within a larger social ecosystem.” As Eve Mitleton-Kelly of the London School of Economics would argue, “Complexity explains why interventions may have un-anticipated consequences. The intricate inter-relationships of elements within a complex system give rise to multiple chains of dependencies.” (3)

Accordingly, I argue for better collaboration between theories of the person, theories of structure, and findings of the fieldwork, to help address how and why trust has turned into distrust in Moroccan political institutions. There is growing disarticulation between state and society that calls for a well-bridged collaboration across social sciences with well-informed insights. I like to perceive us in this room, not as distant academic tribes; but, rather as one league of open-minded analysts with competitive hypotheses and critical perspectives, beyond the ego-driven constraints of the so-called ‘spécialité’.

The challenge is quite laborious as we look at the big elephant in the room: the deepening social malaise and popular resentment of what has become accusative and transformative politics and discourse of blame among the Monarchy, the government, the political parties, the financial elite, and the whole establishment. In recent years, there has been a pattern of dysfunctionality in several sectors of public life, and widening gap between people’s expectations and the state’s performance. We ought not to shy away from deconstructing this dilemma under any pretext of political correctness or avoidance of critical thinking.

As panelists at this conference, we have a common task of addressing two imperatives to the best of our capabilities: First, to perform an accurate sociological diagnosis of the Moroccan politico-societal disjoint between text and practice, body and soul, discourse and trajectory. There are various tools of social sciences at our hands, from social psychology to political sociology, from the basic human needs paradigm to macroeconomics, and from realpolitik to the theories of social movement and collective action. Along the parallel lines between the official discourse and popular narratives that are flooding social media, there are more divergences, which raise new questions about the fluctuations of the social capital, driven by several domestic, regional, and international dynamics.

The second task is to develop in ourselves the confidence of being schizophrenic and acting with two personalities at once. Some of you, by now, may think the conference organizers have made a big mistake by inviting an individual with a mental disorder, or has lost touch with reality, to deliver a keynote speech. Well, let me confess I am truly schizophrenic, by necessity, not to lose touch with reality while seeking deep analysis of the status-quo Morocco.

Therefore, I invite you all to wear two hats: one of the academician/scholar who is well versed in the literature and methodologies of his or her respective field of study. The second hat is of the curious practioner/fieldworker/ethnographer in capturing the deep-rooted causes of the puzzle and eliminating the wrong hypotheses. We need to reconcile the theory-practice question by opening space for them to move freely toward each other in both directions. This is our point of entry into validating any hypothesis about the tension between two forces: top-down status quo versus bottom-up call for change, before we can make any predictions about the trajectory of Morocco’s social change. Mills perceived the sociological imagination as a critical quality of mind, as it “enables us to grasp history and biography and the relations between the two within society. That is its task and its promise.” (4) So, be prepared to wear a possible third hat by the end of my talk!

What Capital, What Decline?

In the last thirty years, several European and American scholars have contributed to social capital theory, namely Pierre Bourdieu in sociology (1984), Robert Putnam in political science (1993, 1996), James Coleman in education psychology (1988), and Francis Fukuyama in economic history (1996). For instance, Putnam argues that "social capital enhances the benefits of investment in physical and human capital", and consists of social networks, which he perceives as a set of "horizontal associations" between people. (5) Other theorists like Janet Holland have positioned social capital between an integration model and a model of injustice and inequality. (6) Social capital also represents “the sum of social stability and the well-being (perceived or real) of the entire population”, and “generates social cohesion and a certain level of consensus, which in turn delivers a stable environment for the economy.” (7)

|

| [Theory] |

However as Oxford scholar and former Director of the Development Research Group at the World Bank Paul Collier, believes, “Social capital needs not be confined to those social interactions which have unintended economic effects.” He asserts the broadest definition of social capital includes government, “since the contribution of government to income is to realize benefits which would not be achieved through the market, and these benefits will be durable because government is itself durable.” (8) This emphasis on the role of the government echoes the significance of gratifying basic human needs, a well-embraced theory in social psychology and conflict studies in the last seven decades.

Within this context, social capital sets the level of trust in the system, the establishment and the entire social organization model. Trust remains a very dynamic variable in the process; and is shaped not only by those socio-cultural networks, but also by public perceptions and reactions. We need to invoke social constructivism here to help map out both structure and agency dynamics. British sociologist Anthony Giddens asserts actors are reflexive; and their reflexivity is an aspect of social action, and, thus, part of structuration.

|

| [Collier] |

At we live at the age of robust social action and protest politics, one should not underestimate the centrality of trust and social capital in the analysis of the Moroccan case, where neither micro- nor macro-focused analysis alone would be sufficient. Individuals, advocacy groups, and local civil society are contesting the monopoly of Makhzen and the so-called ‘servants of the state’ in reproducing the traditional power relations. They are coming to the fore to be part of the process of reforming, remodeling, and modernizing the existing structure. What matters here is neither the agency of the individual nor the power of the structure, but the relational dimension and the outcome of interactivity. This brings us to the concept of ‘duality of structure’. Giddens has formulated this duality as being:"...the essential recursiveness of social life, as constituted in social practices: structure is both medium and outcome of reproduction of practices. Structure enters simultaneously into the constitution of the agent and social practices, and 'exists' in the generating moments of this constitution.” (9)

With the addition of an economic lens into the socio-cultural perspective, the study of social capital remains problematic. It is not a tangible value, and therefore is “hard to measure and evaluate in numeric values.”(10) Recent research has shaped new denominations of ‘human capital’, ‘physical capital’, ‘economic capital’, and ‘cultural capital’. However, the difficulty of shaping a numeric valuation of Morocco’s social capital should not stop us from embracing triangulation, as a powerful technique, in the process of validating recent data from internal and external sources, as well as combining both quantitative and qualitative tracks of inquiry.

I reject the notion of studying Morocco through the prism of the analytical prototype of a post-2011 uprising reality, or a so-called post-Arab spring. In the last seven years, Moroccan developments, either as pro-active mode of popular collective action or reactive Makhzeni management of the crisis, should not be a generic subject matter like in other Arab nations. Instead, I argue for the differentiation between two eras of turbulent politics: The first lasted between February 2011 and October 2016 after activists took to the street in Tangier, Rabat and elsewhere, like other Arab capitals, chanting their demands and putting pressure on the government to fulfill certain specific reforms. Since then, the Moroccan pursuit of reform and democratization remains a ‘one-thousand-and-one-nights’ cliffhanger.

The second era started late October 2016 with the death of Mohsen Fikri in a garbage truck in Hoceima. This particular incident served as a trigger event of reviving the melancholic mutual legacy between the state in Rabat and the sizable Riffian demography in the north and its disgruntled diaspora in Europe. Hirak al Rif has invigorated the generations-transmitted trauma of discrimination between “Almaghrib Annafi’a” [worthy Morocco] and “Almaghrib Rhayr Annafi’a” [not-worthy Morocco], as well as the 1984 stigmatization of Riffians as “awbash” or [savages] by late King Hassan. (11)

Hirak has also accentuated the question about the promised governance and the state’s role in abusing its own political capital and trust. Consequently, Morocco’s social Dow Jones has struggled in making upward strides. Institutionalism and other top-down realpolitik schools of thought in Rabat seem to have exhausted their zeal in maintaining popular subordination, allegiance, nationalism, legitimacy, and other assets of the political capital.

In contrast, there has been unprecedented frequency of protests in Hoceima, Jrada and Guoulmim, strikes of doctors and workers of other sectors, Moqataaa (boycott) movement, and other expressions of deepening social malaise. This growing tide of collective action, or people politics, has entailed a shortage of political innovation and therefore reproduction of the classic discourse. In October 2017, the King’s promise of a possible ‘political earthquake’ sounded promising in installing a mechanism of productivity and accountability. However, the discourse of blame politics and the security-legal paradigm, in which the political establishment has invested heavily in the last two years, have been more symbolic than pragmatic in dealing with those incidents, which remain the iceberg of deeper social malaise.

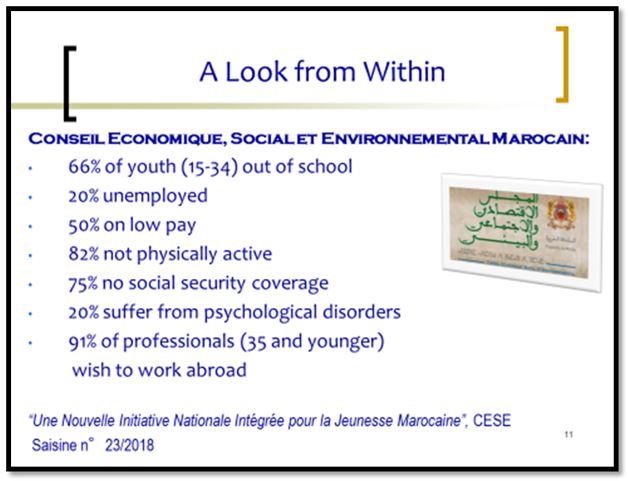

A recent study commissioned by the state-funded Conseil Economique, Social et Environnemental Marocain describes how deep malaise has spread among the youth more than other segments of society. “Two-thirds of young people between the ages of 15-34 are out of school, 20% are unemployed, 50% are on low pay, 82% are not physically active, 75% have no social security coverage, and 20% suffer from psychological disorders.” Concisely, two out of three young Moroccans have abandoned their studies, and one out of five suffers from mental-health issues. The lack of interest in political participation is striking: only one percent belongs to a political party or syndicate. Moreover, 91% of professionals aged 35 and younger wish to work abroad, in search of better work conditions and quality of life, including health care and comfort, thus contributing to Morocco’s brain drain.(12)

|

| [Conseil] |

To say the situation is bleak is an understatement. Local observers have pointed to several “social fractures” in recent years. Moroccan economist Larbi Jaidi explains how the income of 10% of the well-off is over 12.7 times that of 10% of the poorest. The quintile of the richest population already accounts for 48% of the total income against 6.5% for the poorest quintile. (13) As he concluded, “The homogenization of society around the middle class is hindered by the reproduction of social inequalities.”(14) This seems to reflect Moroccan disparity between the 99%-versus-1% global showdown, or the “have-nots” and “have-mores” in a society that lacks opportunities for social mobility with a miniature middle class.

According to the United Nations Development Program, the overall unemployment rate is 9.3 percent. However, it jumps to 18 percent among the youth between 14 and 25. Homicide rate is 1.2 per 100,000 people. Morocco’s human development index stood at 0.667 ranking number 123 among other nations, according to the UNDP report released in September 2018.

The International Organization for Migration highlights that Spain recorded more than 38,000 arrivals by sea and land in 2018. About 7,000 of them were Moroccans. Meanwhile the Moroccan authorities foiled 54,000 attempts to cross the Mediterranean from their shores. In one incident, a Moroccan Navy ship opened fire on a speedboat transporting 20 people and a young girl, Hayat, was killed. Her death triggered deep sorrow and resonance among the Moroccan youth. An article published last October with the title “Young, Educated, Desperate to Emigrate” captured the common feeling of despair and hopelessness. I quote one sentence, “You can either stay and rot to death with no dignity and no opportunities or die on the way out (in the so-called ‘death boats).’’

|

|

[Legatum] |

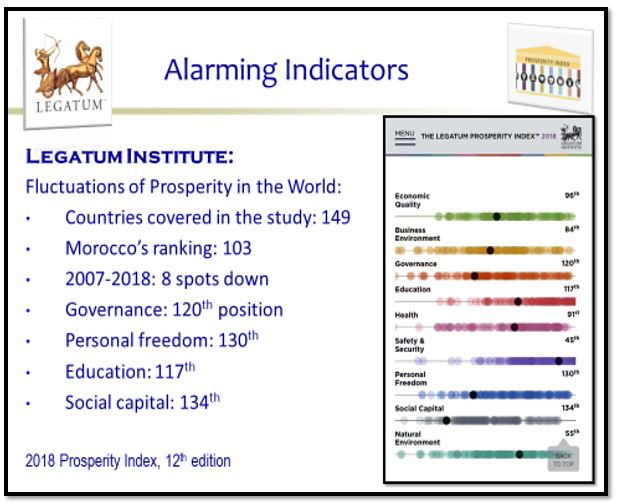

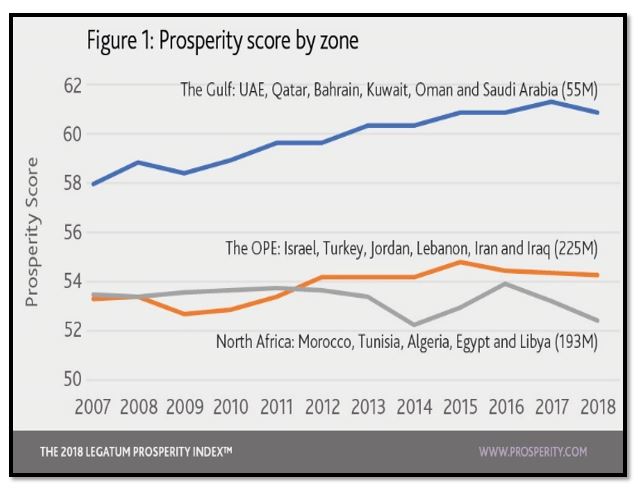

Last November, the London-based Legatum Institute, which “assesses how prosperity is forming and changing across the world”, published its 2018 Prosperity Index. (15) Morocco ranked 103rd among 148 countries, and scored lowest in governance, education, personal freedom and social capital. Morocco’s position has declined eight spots down in comparison with number 95 in 2008. A separate study known as Social Capital World Ranking index issued its 2017 report that covered 180 countries. Morocco came 160 with a score of 37.1 behind Zimbabwe in the 122nd position, Kenya 80th, Spain 37th.

|

| [Legatum Institute] |

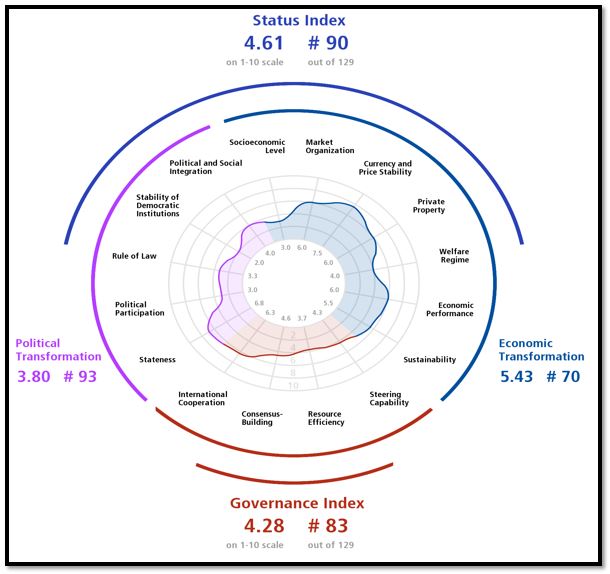

In Germany, the Bertelsmann Transformation Index (BTI) has studied consensus building between political and civil society players in 129 nations in 2018, and rated them on a scale of 1 to 10. Morocco ranks number 83 with 4.6 points behind Algeria, Tunisia, Jordan, Iraq, and Kuwait. In terms of performance and commitment to democratic institutions, the score is lower with 2 points, political participation 3, and political and social capital 4.

Last week, the Economist Intelligence Unit released its 2018 Global Democracy Index after studying 167 countries using 60 indicators across five broad categories: electoral process and pluralism, the functioning of government, political participation, democratic political culture and civil liberties. Morocco ranks 100th out of 165 countries, with 4.99 points out of 10. It is considered one of the hybrid systems between “authoritarian regimes” and “flawed democracies.” The Economist predicts Morocco would continue to struggle with social unrest. “It is unlikely that the underlying causes of the [Rif] unrest (such as the entanglement of politics and big business and widespread inequality) will be fully addressed in the near term.” (16)

|

| [Bertelsmann Transformation Index] |

These internal and external indicators point to a variety of challenges the Moroccan establishment needs to address in 2019 and beyond. Let me highlight three specific drivers of the crisis: a 3-H dilemma, simultaneous vertical and horizontal erosion of social capital, and solidification of a protracted social conflict.

3-H Dilemma: Hogra, Hrig, and Hashtag

The Moroccan youth have internalized three constructs with traumatic connotations within the 3-H dilemma: Hogra, Hrig, and Hashtag. Hogra, a sense of powerlessness and deprivation of dignity; Hrig as an immigration alternative and the pursuit of crossing to Europe even in a risky journey in the death boats; and Hashtag as a conduit of venting on social media. This is an under-studied barometer for growing social malaise. Digital channels and videos circulating on YouTube and Facebook have had incredible reach, and defied certain classical taboos and fear of the power centers in Rabat.

Verticality and Horizontality of the Social Capital Erosion

In the last two years, the social capital decline represents a tree that hides a forest in Morocco. We are now at an interlocking point of two negative trends in this decline: one is vertical, and the other is horizontal.

The vertical decline is political between society and state. Since late 2016, the political establishment has increasingly struggled to maintain its ‘haiba’ [prestige and fear]. According to the ArabTrans project, trust in Moroccan political institutions is among the lowest in the Middle East and North Africa.(17) Larbi Jaidi points to a political practice that “perpetuates the rules governing the functioning of a ‘Court Society’ not only limits itself to weakening the relations of the government with the royal power, but reproduces the functioning of a system built upon clientelism, neopatrimonialism, and the use of politics for financial gain.” (18) This vertical decline correlates with the regression of the national identity into nurturing sub-identities: Amazigh versus Arab, Rifi versus Ayasha, Islamist versus modernist, people versus Makhzen, and so on.

The horizontal erosion of social capital is societal or intra-society. Social trust is very low among Moroccans. More than 80% believe that most people cannot be trusted, according to BTI data. (19) Let us not ignore the ramifications of the fact that 20% of Moroccans suffer from psychological disorders. In 2017, the Moroccan authorities catalogued 559,035 crimes. 18% in murders, 4% in robberies, and 3% in rapes. (20) The cases of rape heard by Moroccan courts doubled in 2018 to 1600 cases. Only in Morocco with the so-called ‘Haqqaoui Law’, it takes a whistle to fight sexual harassment against women at public places.

Social and political capital tends to be hard to earn, but easy to spend. The erosion of this capital deepens distrust in the state, and pushes citizens to regroup in social networks at the golden age of collective action. These networks have embraced communication technology with no physical addresses. The system of mqademin, choyoukh and Qoyad, and the entire state bureaucracy and security apparatus, does not seem to be well prepared to contain, let alone to control, the dynamics of these emerging social networks. The public sphere is embroiled in in-group confrontations and is constructing alternative bonds of various malaise-driven regroupings and solidarities.

Solidification of a Protracted Social Conflict

These trends of decline in both political and intra-society capital entail latent escalation of a Moroccan protracted social conflict (PSC). The mix of failing socio-economic policies, religiosity, and realpolitik, has led to negative shifts in the societal cohesion and deepened disarticulation between state and society within the multi-communal Moroccan society. While developing his new PSC theory in 1990. Arab-American conflict theorist Edward Azar argued, “The process of protracted social conflict deforms and retards the effective operation of political institutions… It reinforces and strengthens pessimism throughout the society, demoralises leaders and immobilizes the search for peaceful solutions. We have observed that societies undergoing protracted social conflict find it difficult to initiate the search for answers to their problems and grievances.” (21) Apparently, Morocco is at this stage of political fatigue and loss of compass.

Conclusion

In closing, Morocco remains captive of a battle between two rival legitimacies: one bottom-up legitimacy that derives from popular grievances of basic human needs and demands for reform versus a top-down legitimacy that echoes state institutionalism, the rule of law, and other frames of the power paradigm. The analysis of the recent protests’ slogans and social media content indicates how the bottom-up demands of accountability have gone higher than the political parties and government. It has become common conviction the buck stops with the Monarchy.

Looking forward, I cannot stress enough the need for shifting the unit of analysis from institutions and systems to the human dimension. One needs to stand at the intersection between individuals and institutions, between society and state, and reflect on how social change shapes itself. To help address the problem of distrust in the political institutions, we need to wear a third hat as I mentioned earlier. As we aim hopefully, at this conference and beyond, to do a thorough sociological diagnosis, reconnect text to reality, and rekindle the missing love between society and state, we need to be trusted and reliable mediators between society and state by providing non-partisan perspectives on how to shape sound public policies in the future. This is the moral imagination of the intellectuals when they decide to engage with their societies and help design a vision of change and a compass for the road. We can be a catalyst force of reason and critical thinking to help initiate a new chapter between the top and the bottom. I like to leave you with one question, one reflection: do we have a Moroccan sociological imagination?

|

| [Al Jazeera] |

(1) Joachim Vogt Isaksen, “The Sociological Imagination: Thinking Outside the Box”, Popular Social Science, April 19, 2013 http://www.popularsocialscience.com/2013/04/29/the-sociological-imagination-thinking-outside-the-box/

(2) Mills, C. Wright. The Sociological Imagination (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1959), 5, 7.

(3) Mitleton-Kelly, Eve. Ten Principles of Complexity and Enabling Infrastructures. Complex Systems and Evolutionary Perspectives on Organisations: The Application of Complexity theory to Organisations. s.l. : Elsevier, 2003

(4) Mills, C. Wright. The Sociological Imagination (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1959), 5, 7.

(5) Putnam, R. 1993. "The Prosperous Community-Social Capital and Public Life." American Prospect (13): p. 36

(6) Holland, J. “Fragmented youth: social capital in biographical context in young people’s lives”, in R. Edwards, J. Franklin and J. Holland (eds) Assessing Social Capital: Concept, Policy, Practice, (2007) Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Press

(7) The Sustainable Competitiveness Report, 6th edition November 2017 http://solability.com/the-global-sustainable-competitiveness-index/the-index/social-capital

(8) Paul Collier, “Social Capital and Poverty”, Social Capital Initiative, Working Paper No. 4, The World Bank Social Development Family Environmentally and Socially Sustainable Development Network, December 1998

(9) Giddens, A. Central problems in social theory: Action, Structure, and Contradiction in Social Analysis, 1979, Los Angeles, CA: University of California Press.

(10) The Sustainable Competitiveness Report, 6th edition November 2017 http://solability.com/the-global-sustainable-competitiveness-index/the-index/social-capital \

(11) The Economist, “Morocco’s unrest is worsening:”, July 8, 2017 https://www.economist.com/news/middle-east-and-africa/21724804-trouble-neglected-region-threatens-whole-country-moroccos-unrest

(12) Rapport du Conseil Economique, Social et Environnemental, “Une Nouvelle Initiative Nationale Intégrée pour la Jeunesse Marocaine”, Saisine n°23/2018 http://www.cese.ma/Documents/PDF/Saisines/2018/S32-2018-Strategie-integree-des-jeunes/Rp-S23-vf.pdf

(13) Larbi Jaidi, Economic and Social Change in Morocco: Civil Society’s Contributions and Limits”, The Arab Transitions in a Changing World, IEMed, 2016

(14) Larbi Jaidi, Economic and Social Change in Morocco: Civil Society’s Contributions and Limits”, The Arab Transitions in a Changing World, IEMed, 2016

(15) The Legatum Institute, 2018 Prosperity Index, 12th Edition https://www.prosperity.com/

(16) The Economist, The retreat of global democracy stopped in 2018 Or has it just paused? January 9, 2019 https://www.economist.com/graphic-detail/2019/01/08/the-retreat-of-global-democracy-stopped-in-2018

(17) Bertelsmann Transformation Index, Morocco-Country report, 2018 https://atlas.bti-project.org/share.php?1*2018*CV:CTC:SELMAR*CAT*MAR*REG:TAB

(18) Larbi Jaidi, Economic and Social Change in Morocco: Civil Society’s Contributions and Limits”, The Arab Transitions in a Changing World, IEMed, 2016

(19) Bertelsmann Transformation Index, Morocco-Country report, 2018 https://atlas.bti-project.org/share.php?1*2018*CV:CTC:SELMAR*CAT*MAR*REG:TAB

(20) US State department, Morocco 2018 Crime & Safety Report, Bureau of Diplomatic Security, https://www.osac.gov/Pages/ContentReportDetails.aspx?cid=24353

(21) Azar, Edward. The Management of Protracted Social Conflict: Theory & Cases, Aldershot, Dartmouth, 1990 p. 16.