|

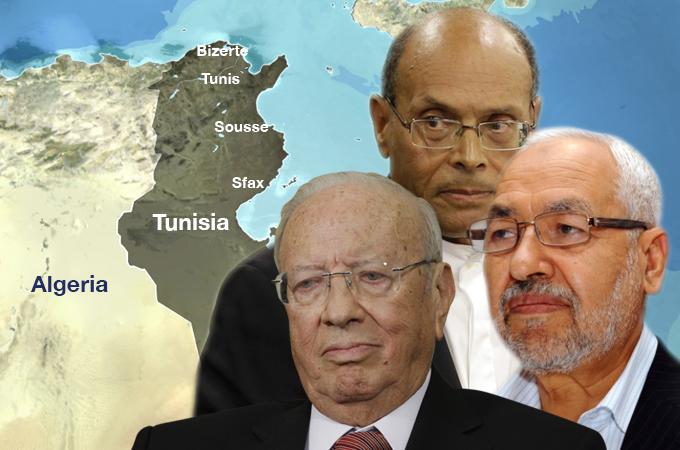

| [AlJazeera] |

| Abstract Tunisia appears less confident about the future of its democratic transition than ever. In addition to growing economic challenges, security problems have deepened the political crisis. The opposition has taken advantage of the security difficulties facing the government to cast doubts on the political process and institutions, especially the National Constituent Assembly, which is supposed to produce a new Tunisian constitution. At the level of security, armed attacks have succeeded, at a time when the opposition with all its civil forces has failed, to obstruct the transition. In the context of the national dialogue, consensus over the next prime minister is one major difficulty, but the other is the relationship between the next government and the National Constituent Assembly. While the governing troika – comprising Ennahda, Congress Party for the Republic (CPR) and Ettakatol – is seeking to set a binding date for elections and for the ratification of the constitution, which is its condition to step down from power, the aim of the opposition seems to be, despite the different objectives of its factions, to install a government loyal to it, regardless of whether there will be a balance of forces within the Constituent Assembly. The governing troika is not in a hurry to set dates for the election and for the ratification of the constitution. It is, rather, willing to do whatever it takes to win the next government. As a result of the pressure to move towards a political solution to the current crisis through dialogue, everyone feels compelled to compromise and to use dialogue to seek possible side deals. |

Introduction

For the past few months, Tunisia has appeared less confident in the future of the democratic transition than it was a year ago. In addition to mounting economic challenges, which led to unprecedented decline in the value of the local currency, the security problems have deepened the political crisis, and the opposition has shown remarkable skill in exploiting the difficulties the government is facing in its confrontation with the armed groups to discredit the entire political process. In fact, it has staged activities aimed to dissolve the only elected institutions in the country, especially the National Constituent Assembly, which is mandated with giving Tunisians their new constitution.

Political and security developments

Since the assassination of the leftist opposition leader, Chokri Belaid, armed attacks have followed the rhythm of the political process. These attacks have been successful where the opposition and all its civil forces failed – in obstructing the transition process. The same happened through the assassination of pan-Arabist leader Mohamed Brahmi on the anniversary of the republic on 25 July, and one day before the election for the Independent High Elections Commission, which will oversee the next election. Investigations into recent bombings targeting tourist sites in the resort cities of Sousse and Monastir, have not yet established whether they were suicide attacks or not. These attacks did, however, exacerbate fears of a security crisis in Tunisia since the government declared Ansar al-Shari’ah a terrorist organisation.

Many armed attacks had been foiled pre-emptively. Despite unprecedented losses in the ranks of the military and the National Guard, many militant cells were dismantled, while others are being besieged in their hideouts in the rugged areas in the west of the country. However, intelligence reports confirm that Ansar al-Shari’ah, which has not claimed responsibility for any of the attacks, has witnessed a state of disintegration and defections from some cells, which engaged in reprisals without effective central planning. Despite what might be described as success of the security services, this would weaken the ability to anticipate what further and more powerful attacks sleeper cells might perpetrate. From a political-security perspective, the fact that Ansar al-Shari’ah has not claimed responsibility for any of the attacks raises many questions. A new group in Tunisia, Ansar al-Shari’ah, and the Salafi jihadi organisations in general are known for being easily penetrated, a fact that has been demonstrated through investigations.

Cells that have been exposed looked like they had been hastily formed. Most of their members had only recently joined the jihadi movement, but, for the most part, they included a number of persons with criminal records, and some former security personnel who had been dismissed from service. This raises questions about the possibility of the organisation being infiltrated by an intelligence agency linked to political interests. This makes sense when it comes to interpreting some of the attacks blamed on the organisation. Intelligence reports on some of the organisation’s field commanders indicated that the long-term goal of the insurgency was to help remove the Ennahda party from government, and facilitate the opposition’s rise to power. Through this, the organisation would eliminate doubts about the legitimacy of fighting the incumbent government, and pit the Salafis in an open and direct struggle against those whom they consider authentic enemies of Islam, namely, parties linked to the former regime and to leftwing parties.

At the same time, the interior ministry, which is still staffed by individuals affiliated with the former regime, is not responding to the armed attacks with its full capacity. That is because there are elements within who block the flow of information, and hinder appropriate reactions to threats. As a result, the government seems incapable of addressing the security problems, a fact that was especially evident on 14 September 2012, with the events at the US embassy in Tunis, and the assassination of Brahmi. The authorities are confronted by the obvious desires of the security forces to have a free hand to re-impose the old security regime under the pretext of counterinsurgency. This would mean the return of the old regime, not only in its political form, but also in its security character, thus burying the ambitious transition to democracy.

The challenges and future of the national dialogue

The four civic organisations led by the General Union of Tunisian Workers (UGTT) succeeded in bringing together several political parties to the national dialogue table, in setting a calendar for the remaining milestones of the democratic transition, and in forcing the different parties to sign it. In light of the challenges that the organisations identified in their roadmap, three committees were formed: the committee on government (which is expected to reach consensus on the next prime minister so that it can complete the process and oversee the elections), the committee in charge of the electoral process (to agree on an electoral calendar, including the date for the poll), and the committee on the constitution (to agree on how to overcome the final difficulties facing the drafting of the constitution, ratify it and complete the outstanding jobs of the Constituent Assembly). Although the initiative emphasises synchronization and parallelism between these three tracks, each side entered the dialogue with a clear intention. The troika’s concern was the ratification of the constitution and the setting of a date for elections; the opposition entered primarily to effect a change in government.

Despite some delay, which has made it impossible to honour the deadlines set by the roadmap, the constitution committee has made remarkable progress, in parallel with the work of the committee tasked with reaching consensus within the National Constituent Assembly. The former successfully addressed almost all the problems that have recently hindered the drafting of and voting on the constitution. Two partners in the troika – Ennahda and the CPR have to make concessions on the issue of the political system and the powers of the executive branch of government. This suggests that the next constitution will provide, along with the widest possible margin of freedoms, more balance between the two heads of the executive branch: the prime minister and the president.

On the other hand, the committee on government is clearly stumbling. Participants have not yet agreed on a candidate for premiership, because most dialogue participants are from the opposition, which seeks to impose its nominee on Ennahda, even though it controls the majority in the Constituent Assembly. In fact, some opposition leaders have proposed a vote on the candidate within the national dialogue, and refused to suggest more than one candidate. The national dialogue has transformed into an attempt to neutralise the Constituent Assembly, which shifted the balance between the majority and minority as produced by elections. This means that, for many, the dialogue was intended to terminate the new system created by elections.

Although Ennahda did not provide a candidate for premiership, it supported the nomination of Ahmed Mestiri, the candidate from Ettakatol, an Ennahda ally. Mestiri is called the ‘father of democracy’ in Tunisia, and is widely respected by Tunisians. The opposition factions – both the left and right wings, meanwhile, backed liberal figures, some of whom had played a role in the former regime, while others had served with Beji Caid Essebsi, leader of the Nidda Tounes – which is the heir of the old regime, and head of the government that preceded the October 2011 elections.

After a week of heated debate and leaks, rumours and reciprocal psychological warfare, two nominees remained in the race: Ahmed Mestiri and Mohammed Nasser, minister of social affairs in Essebsi’s government, who had resigned from his government post in December 1977 prior to the 26 January 1978 bloody crackdown by the authorities against trade unions. As expected, the parties did not reach a consensus on either candidate, opening the door again for the nomination of independent figures, both from within the government and from outside, especially after UGTT secretary general, Hussein Abbasi, announced on 4 November the suspension of the national dialogue, citing the failure in the committee for government.

Not reaching consensus on the head of government is not the only major difficulty facing the national dialogue. More critical is the future relationship between the government and the National Constituent Assembly. The national dialogue has led to concern among parliamentarians who feel that the role of the assembly is being diminished, especially as the opposition seeks to change the provisional law governing public authorities in a manner that would prevent the next government from being held to account and thus prevent it being removed. In this context, a broad front began to take shape, led by the CPR, which refused to participate in the national dialogue as presented by its patrons. The front includes other parties and groups of independents, and seeks to preserve all the powers of the assembly and address any attempts to change the provisional law governing public authorities.

These elements seem interrelated, interactive, and influenced by what is happening – or could happen – outside the dialogue chamber and the Constituent Assembly. If we add the implications of any potential security incidents, it would be difficult to predict what the outcome of the current processes would be. However, there remain important cards in the hands of the president, who may not accept any candidate suggested to him, thus undermining the opposition’s choice, even if it managed to impose its candidate on Ennahda. That explains the attacks being waged by prominent opposition figures against President Moncef Marzouki, which describe him as the main obstacle to the current path, as he may prevent the opposition from reaping the fruit of their efforts.

Troika options and opposition options

The landscape seems complicated. It is less complicated to figure out what the troika and the opposition want for the next stage. On the one hand, the troika seeks to arrive at a binding date for elections and for the ratification of the constitution, after which it will agree to leave government. For the opposition, despite the differences in the agendas of its factions, its joint goal is to install a government loyal to it, regardless of the balance of power within the Constituent Assembly. It also seems not to be in a hurry regarding the election date and the endorsement of the constitution. However, it is ready to pay the price for winning the next government.

No one expects any of the parties to get everything they want. In fact, some key players have begun talking about shifting from an independent government of technocrats to a party quota-based or a national unity government. With this in mind, if no security surprises occur to disrupt the current trajectory, the next government will be under the control of the assembly like its predecessor. It will be led by independent persons other than those currently nominated, and will be based on a quota system – whether directly or indirectly. This will necessarily make it a fragile government, and it will be pushed to expedite the election and wrap up all the stages of the current transitional process.

There is speculation that the main opposition faction, Nidda Tounes led by Essebsi, has indicated a desire to share power with Ennahda, but this has been categorically rejected by Ennahda’s leadership. However, it is not too late for such a deal to take place. It would, however, lead to dismantling the existing alliances in the troika and in the opposition ranks. However, the most important obstacle to the completion of this deal remains the incumbent president, who said he would only hand over the presidency to an elected president.

The Tunisian arena is linked to the regional and international situation, a fact which sheds light on other dimensions of the current political crisis. At the regional level, Tunisia is experiencing the consequences of the economic downturn in southern Europe, which makes it difficult for it to attract new investments, and complicates the economic situation. The opening of the Tunisian border with Libya has increased security threats against the transitional process, as weapons used in recent armed attacks came from Libya, and all participants in these operations have been to Libya for training. Algeria, the large neighbour, believes that the delay in finding a political solution will facilitate the spread of the insurgency and increase threats to Algeria.

The momentum gained by the opposition probably started with the military coup against President Mohamed Morsi of Egypt. It was a breath of fresh air for the old regime in Tunisia, and has enabled the left to gain greater boldness. Both defended the massacres in Egypt, and justified them. The Americans and Europeans made it clear that they wanted to see the success of the democratic experience, and wanted Egypt to regain its regional power, while they turned a blind eye to the coup. Tunisia does not represent a regional power and is not involved in conflicts beyond its border; thus its success in overcoming the current phase is merely symbolic for the West.

Much money is currently being funnelled into Tunisia in an environment that is difficult to control. Recipients include certain political parties and organisations. The funds are used to mobilise the street or finance armed attacks.

After the coup in Egypt, there have been mounting fears of a similar coup in Tunisia, funded by foreign countries. That prompted new appointments in the army, and the interior ministry aimed to prevent the opposition from getting what they have been seeking since the Egyptian coup, which is to see a military or security coup against the troika, followed by power being handed over to the opposition. Despite the naivety of this perception, the troika dealt with it seriously. The fears of scenarios similar to those in Egypt pushed Ennahda to offer compromise after a compromise, so much so that its leadership accepted the Quartet Initiative despite rejecting its rules. No longer was the question about the performance of Ennahda. Instead of ‘Will Ennahda compromise?’, it became ‘To what extent will Ennahda compromise?’

Conclusion

As a result of the pressure to accelerate efforts for a political solution to the current crisis through dialogue, it seems everyone has been forced to compromise, and to look for possible side deals, suggesting that the crisis will soon find a political solution, albeit a little late compared to what the Quartet had planned. But no one in the end will achieve all their objectives or prevent others from achieving theirs. Optimists believe that the crisis will be resolved as soon as an agreement on the next prime minister is reached. However, they overlook the difficulties of forming a government, the challenge of winning the confidence of the Constituent Assembly, and the security problems that might result during or after the appointment of a prime minister. Others believe that the problem is more complex than just the formation of a government, as the troika and the opposition are engaged in a conflict between an old regime that does not want to die, and a new system striving to be born.

Breaking the links between armed attacks and political agendas is important for the stability of any new government. Meanwhile, other institutions are watching the political parties as they attempt to bypass the authorities to keep in their hands the cards that render any new government effective or ineffective.