Europe is among the most affected regions in the world by the spread of COVID-19. The continent was designated in March 2020 as the new epicenter of the pandemic and Europe’s recovery strategy to the crisis seems to be threatened by a lack of solidarity. This paper analyses how the European Union (EU) governance system has – so far – conditioned the construction of a modest coordinated European response to the crisis. It examines how the insufficiencies of the EU governance system have – so far – conditioned the construction of a modest coordinated European response to the crisis. It suggests that COVID-19 is a learning opportunity(1) rather than a make-or-break event. Crises in the EU are important catalysts of change(2) and offer a propitious context for policy learning.(3)

This paper suggests that COVID-19 is a learning opportunity rather than a make-or-break event. Two lessons are highlighted: first, this crisis shows that if Europeans bet on solidarity as an incentive to cooperate, their chances to produce prompt and ambitious responses are slim and overshadowed by power-struggles on what the governance of the EU ought to be. Second, while the crisis started as a public health problem, the crux of the debate is now centered on a common economic recovery strategy. The challenge ahead will be to avoid that lessons learned about public health are cannibalized by economic affairs.

Since January 2020, the COVID-19 crisis has delivered ample blows to Europeans: first with the fulgurant increase in deaths due to COVID-19, then with a justified halt on all social contacts, and finally with economic consequences so dire they indiscriminately affect the population. The European Union’s response has been scorned as poor,(4) and commentators have denounced the EU’s inaction in both public health and economic affairs. Indeed, the EU has so far given the impression of a union in disarray: Member States produced scattered responses on the issue of protecting citizens’ health and then seemingly failed to find an agreement on stimuli to cope with economic depression.

Reports(5) and early academic publications(6) have pointed that a logic of “every man for himself” had superseded a political project unable to crystallize a sense of solidarity among its 27 Member States. Yet, if “solidarity” were the active compound that holds the Union together, the EU might as well be a simple forum in which Member States cooperate and help each other. In effect, the EU is built on strictly enforced legal ties that bind national governments with one another. Member states act in concert because a complex legal order binds them together rather than because of the attractiveness of collective action.

Public health is a policy area in which the EU does not have binding instruments;(7) and while the Eurozone is an integrated monetary union, fiscal and economic affairs remain in the hands of Member States. These limits to the EU governance system have proven to be an explosive cocktail in the COVID-19 crisis, and they have exacerbated fears about Europe’s ability to recover post-crisis. The claim defended here is that rather than the marker of a form of disintegration of the Union, Europe’s lack of a coordinated strategy is the symptom of a deficient governance system for crisis contexts. A Union purely based on solidarity rather than a binding legal framework is sub-optimal, because it rests on the good will of Member States and delays decision-making in times of crisis.

Amid crisis, learning is constrained by time pressure, choice opportunity is reduced.(8) Europe’s strategy vis-à-vis the COVID-19 is a compelling case of policy learning albeit one that demonstrates asymmetrical effects in public health and economic policy. While the crisis started as a public health problem, the crux of the debate is now centered on a common economic recovery strategy:

- First, the haphazard European response on the public health front is explained by shedding light on the limits of the EU’s governance system. In effect, on the matter of public health no ambitious coordination emerged between European countries and the logic of “every man for himself” has prevailed. In this area expectations to observe policy learning are limited because of the economic crisis cannibalizing the public debate.

- Second, Europe’s difficulties in building a common economic recovery strategy are appraised: while resistance to building mechanisms of fiscal solidarity is substantial, so is the opportunity for learning and enacting a sizeable change. Policy learning may thus eventually lead to substantial reforms of the governance system, but the EU’s current metaphorical policy toolbox remains ill-equipped for fast-paced response amid crisis.

A Haphazard Public Health Response

Viruses do not know borders, nor do they travel alone. They thrive on goods, usually perishable ones, as well as people. Freedom of movements for goods as well as persons is a cornerstone of the EU(9) and has made public health crises a European problem rather than a national one. To the uninitiated, there is something quite logical in assuming that the EU is competent where its Member States are mutually dependent. Yet, public health is far from being integrated: the EU has limited competences in harmonizing epidemiological surveillance(10) and Member States are usually wary to avoid any encroachment on the actual management of health threats. The management of health crises thus rests on a system of soft governance, which involves the use of non-binding rules that are nevertheless expected to produce effects in practice.(11) With COVID-19, European states initially relied in a limited way on this soft-coordination mechanism. However, as the saliency of this crisis increased, national governments have engaged in more cooperative endeavors.

1. Limits to Public Health Governance in the EU

Public health governance in the EU is characterized by a sharp division between risk assessment and risk management.(12) Risk assessment is the identification of risks through the evaluation of the magnitude, mechanisms and gravity of threats to public health. In the EU, this task is carried out by the European Commission (DG SANTÉ). This function requires important scientific work which the Commission delegates to an independent agency: the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) created in 2004. The ECDC gathers epidemiological information from Member States’ health agencies across the EU as well as neighboring third countries (Norway, Iceland and Lichtenstein). EU institutions are thus expected to take on a role of fire alarm in framing epidemiological threats as transnational health problems.(13)

The counterpart to this is risk management: treatments such as vaccination and restrictions such as confinement(14) remain the prerogative of national authorities. At EU level, Member States meet in the Health Security Committee (HSC), a group formalized in the aftermath of the 2009 H1N1 crisis and made up of national Health Ministries’ representatives.(15) The HSC is a forum meant to facilitate the coordination of national responses to health threats. In terms of coordination, the European legal framework is limited to a voluntary mechanism for the joint procurement of medical countermeasures(16): Member States may mutualize their purchase of medical equipment.

In effect, this system of governance sets-up clear practical limits to the production of a coordinated response. At national level, assessment and management are two sides of the same coin: public health agencies are not constrained by the same limits to its mandate than ECDC. For instance, during the COVID-19 crisis the French health agency has even been expected to publicly advise the French government regarding containment. Unlike at national level, independent experts in the ECDC cannot demonstrate a form of entrepreneurship amid crisis and thus cannot be the catalyst for a coordinated answer. Moreover, the last evaluation of the ECDC(17) highlighted important flows in the coordination of preparedness for pandemics. These characteristics raise questions on the workability of this system, specifically in terms of reactivity amid crisis.

2. The Ball is in Member States’ Courts

The European experience of the COVID-19 crisis was characterized in January and February 2020 by a “casual approach” which did not spare those in charge of framing risks. On 9 January 2020, the ECDC considered the likelihood of an introduction of the virus in the EU as low.(18) The blame is probably not to be attributed specifically to EU institution but rather to the wait-and-see attitude that characterized most of the occidental world in the early weeks of 2020. To add to the confusion, the pandemic affected EU Member States unevenly.(19) Italy was the first Member State to experience a sharp increase in deaths linked to COVID-19 and was the first one to rely on restrictions on the free movement of persons in the last week of February 2020.(20)

Other EU Member States followed Italy’s footsteps: they enforced a “lockdown” on their population and re-established controls at their borders. Each member state did so unilaterally, with precipitation and without attempts to coordinate the process, in spite of Heads of State and Government of the 27 EU Member States meeting via videoconference on 10 March 2020(21) and the European Commission producing a communication(22) to coordinate temporary restrictions on non-essential travel on 16 April 2020. Slovakia, Czech Republic enforced border controls from 12 March, the day after, Denmark, Poland, Latvia, Lithuania and Cyprus followed their lead, while Germany, Spain and France initiated these restrictions from 16 March 2020.(23)

Time had been wasted on seizing the breadth and depth of this crisis, which narrowed drastically the window of opportunity for Member States to coordinate their response to the crisis. Rules regarding confinement have been different from one country to another: for instance, the enforcement of those rules in France has been described as strict,(24) while the Hungarian government’s emergency measures have been denounced as threatening the rule of law.(25) At the other extreme of the spectrum of responses Sweden took a “no-lockdown” approach, resulting in up to five times more COVID-19 related deaths than its immediate neighbors.(26)

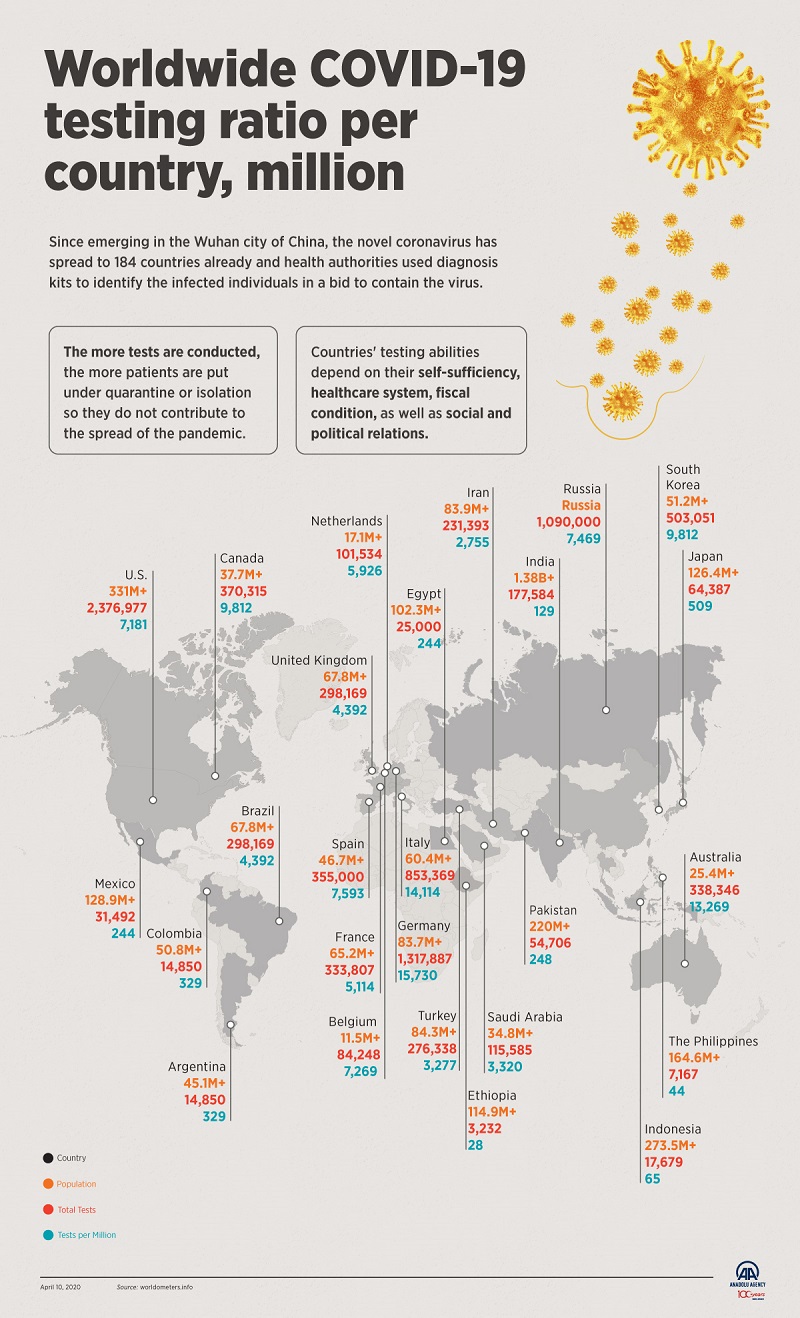

On top of producing different responses, EU Member States have displayed staggeringly different levels of preparedness, for instance with vastly different stocks of personal protective equipment (PPE) and unequal access to test kits.(27) This prompted a surge of generosity with some PPE graciously sent to Italy by its neighbors,(28) or French patients flown to Germany to avoid a saturation of hospital beds.(29) Eventually, European states activated the mechanism of joint procurement of medical equipment on 28 February 2020 for personal protective equipment and on 17 March 2020 for ventilators.(30) Additionally, on 15 March 2020, the European Commission required that Member States monitor exports of PPE. However, this occurred after Member States attempts to implement similar measures at national level,(31) thus accentuating the logic of “every man for himself”.

Overall, while the EU’s public health governance is a system with important limits, European states unwillingness to cooperate has also been detrimental to produce a common response. Considering the workability of this system, it is not amid crisis that cooperation is most likely to produce results. A lesson of the COVID-19 pandemic for the EU is that public health measures based on coordination produce better result if they are used to prepare rather than mitigate a public health crisis.

3. Lifting Containment Measures

On 15 April 2020, the European Commission presented a roadmap to lift containment measures.(32) The Commission’s document is based on epidemiological indicators such as the decrease in new infections, and hospital admissions; considerations linked to national health systems; and guarantees regarding epidemiological surveillance.

European countries have displayed somewhat higher level of coordination regarding the progressive lifting of containment measures. Except for Italy, which had initiated its lockdown before any other country and lifted some containment measures on 4 May 2020. France, Belgium, the Netherlands Germany, Austria, the Czech Republic, Greece, Bulgaria, Estonia, Finland, Ireland and Romania eased-up containment measures on 11 May 2020,(33) while enforcing relatively similar guidelines regarding use of PPE in public space. Freedom of movement between European countries has however not been fully re-established. Here again, there are notable differences between EU Member States who have enforced a lockdown in the first place. Germany, Croatia, Hungary, Portugal, Czech Republic refuse new entries on their territory. Belgium, Cyprus, Denmark only accept entries for essential reasons (work, assistance to dependent persons). The rest of European countries imposes quarantine measures on new entrants.(34)

This limited form of coordination in lifting containment measures shows that European Countries are warier of their interdependence. However, while the epidemiological situation has improved according to the ECDC,(35) Europeans willingness to return to normal is fundamentally motivated by economic incentives. On 13 May 2020, the European Commission presented a series of recommendations on re-establishing freedom of movement in the EU.(36) The rationale presented in the document is to soften the economic blow and to allow tourism businesses to reopen, after months of lockdown, while respecting necessary health precautions.

The issue of economic recovery – detailed in the next section – is thus clearly dominating this new phase of mitigation and exit of the COVID-19 crisis. While this is unsurprising, it bears an important risk. Europeans have experienced this health crisis with a scattered response, and some are asking for ambitious reforms of the governance of public health in the EU.(37) The challenge ahead will be to avoid that lessons learned about public health are cannibalized by economic affairs.

Looking for a Common Economic Recovery Strategy

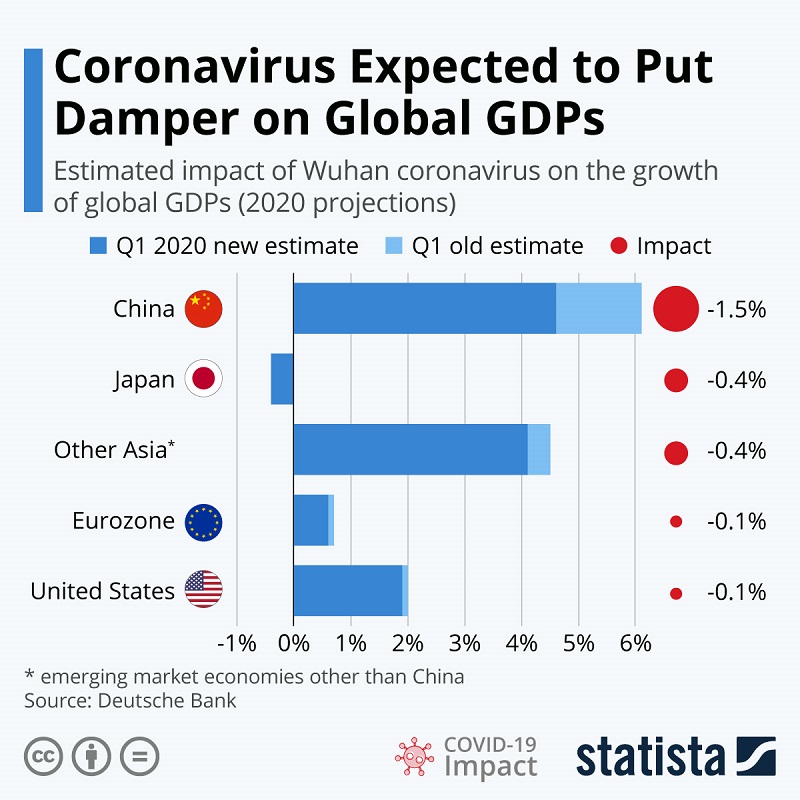

Containment measures have a profound impact on the EU’s economy. Indeed, even before confinement measures had been decided, social distancing measures had already impacted growth in European countries.(38) Economic consequences will be important globally, but here again in the EU, the system of governance adds a layer of complexity for a common recovery strategy. Much like in the case of public health, the economic governance of the EU is based on a sharp division of competences. The European Central Bank (ECB) is an independent body with full competence on monetary policy for the Eurozone (the monetary union of 19 of the 27 Member States of the EU). Fiscal policy and economic policies are national prerogatives, albeit Member States achieve some form of coordination in this area in the Eurogroup, an informal group of the finance ministers of the Eurozone.(39)

A thorny issue in the monetary union has been, especially since the 2008 financial crisis, the question of financing national debts. The ECB can do so in a very limited way via quantitative easing (purchasing member states’ debt on the secondary market). While the president of the ECB had initially declared in February 2020 that the ECB would not resort to exceptional measures,(40) the ECB rapidly took a turn on 10 March 2020 and dropped limits on its quantitative easing program.(41) Quantitative easing is however a precarious solution, as the debate is still vivid regarding the legality of the ECB’s move.(42)

A more permanent solution would be to mutualize at least part of national debts via Eurobonds.(43) The idea is that through these Eurobonds, Member States with large debts could effectively finance their budget via the same mechanism and at the same rate on the market than member states with balanced budgets. This proposal has been traditionally opposed by the more fiscally conservative northern European states. With the economic consequences of COVID-19, the question of Eurobonds was pushed center stage again, this time under the name of Coronabonds.

1. Reforming Fiscal Governance amid a Public Health Crisis

During the afore mentioned meeting of Heads of State and Government of the 27 EU Member States on 10 March 2020, the French and Italian governments called for more economic coordination. The suggestion of Coronabonds was met with circumspection by the more fiscally conservative European countries, including the German and Dutch government.(44) At the end of the meeting, the President of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen, who is herself not in favor of Coronabonds,(45) presented a first recovery plan aimed at supporting European states in their fight against the epidemic with 25 billion euros to support the economy and various health systems. However, there was no mention of an innovative instrument for debt mutualization, as per the wish of some member states.(46)

The COVID-19 crisis has once again shed light on the cleavage between a fiscally conservative North and an expensive South but what appears today as a lack of solidarity, is in effect the display of power struggles on how to address deficiencies of the economic governance of the Eurozone. While the financing of national debts is an attractive model, fiscally conservative governments refuse to create a precedent which would further erode their sovereignty in economic affairs. The negotiations that we have witnessed during the COVID-19 crisis are thus more intricate than a simple erosion of solidarity in the EU: there are not just about recovery but about the future governance of the Eurozone and here again the system of governance is not the most workable amid crisis.

2. The Way Forward

Coronabonds will probably not come to fruition soon, but common measures for recovery have been agreed by European countries, including an ambitious Franco-German proposal, yet to be agreed by the other member states. On 9 April 2020 the Eurogroup adopted a 540-billion-euro stimulus package based on loans for small and medium-sized businesses;(47) a European instrument for temporary support to mitigate unemployment(48) and access to the European Stability Mechanism (ESM) which aims to provide financial assistance to member states in times of crisis.

While these measures provide some important relief, the issue of financing debt is still ongoing. On 23 April 2020, heads of State and Government met for the fourth time since the start of the Covid-19 crisis. If all agreed on the need for the Union’s budget revised upwards and adapted to the coronavirus crisis, European governments have different positions on how to use these new resources. Here again, the issue of solidarity is less important than the question of sovereignty. Italy, Spain and France support an integrationist solution: European loans subscribed directly by the Commission to fund member states in the form of grants. The fiscally conservative states defend a more sovereigntist option: loans contracted by the states but guaranteed by the European budget.(49) This solution would allow the most indebted states to borrow at a lower cost (the European guarantee would even make them more credible on the markets), but it would not exempt them from repayments and interest rates.

A way forward might lie with the recent Franco-German proposal which symbolizes the consensus between fiscally conservative North and expensive South.(50) On 18 May 2019, French president Emmanuel Macron and German Chancellor Angela Merkel suggested the adoption of a stimulus fund of 500 billion euros which would be integrated into the multiannual budget of the EU and would allow the European Commission to redistribute the money to the regions most affected by the epidemic, under the form of loans and not grants. The plan was hailed as ambitious.(51) The Franco-German proposal could be the embryo of an “Hamiltonian” moment for fiscal federalism if this mechanism becomes formally integrated to the governance of the governance of the eurozone. While the Spanish and the Italian government have voiced their support, it remains to be seen how palatable the idea of grants will be to the other fiscally conservative countries: Austria, Denmark, Sweden and the Netherlands.

Europe Can Learn from the Crisis

COVID-19 has shed light on the baroque governance of both public health and economic policy in the EU. With their respective distinctions between EU competences and national competences, these systems of governance remain ill-equipped to react promptly to crises. A paradox of these events is that they foster learning: the deficiencies that were described here have never been so obvious than during the COVID-19 crisis. Amid crisis, European leaders are constrained by time pressure and their choice opportunity is reduced: while negotiations are still taking place on the Franco-German proposal, evidence shows that key member states are starting to forge consensus on both a recovery plan and the future of the Eurozone. In terms of public health, lessons learned on cooperation do not appear to be as resonant and public health actors should remain vigilant if their hope is to see further integration take place, especially regarding preparedness for future crises. Overall, this crisis shows that if Europeans bet on solidarity as an incentive to cooperate, their chances to produce prompt and ambitious responses are slim and overshadowed by power-struggles on what the governance of what the EU ought to be.

(1) Kamkhaji and C. M. Radaelli. ‘Crisis, Learning and Policy Change in the European Union’. Journal of European Public Policy, Vol. 24 (5) 2016, pp. 1–21.

(2) S. Saurugger and F. Terpan. ‘Do Crises Lead to Policy Change? The Multiple Streams Framework and the European Union’s Economic Governance Instruments’. Policy Sciences, Vol.49 (1) 2015, pp. 35–53.

(3) E. Deverell, ‘Crises as Learning Triggers: Exploring a Conceptual Framework of Crisis-Induced Learning’. Journal of Contingencies and Crisis Management, Vol.17 (3) 2009, pp. 179–88.

(4) L. Bayer, ‘EU Response to Corona Crisis “Poor,” Says Senior Greek Official’. POLITICO, 1 April 2020. https://www.politico.eu/article/eu-response-to-coronavirus-crisis-poor-….

(5) S. Michalopoulos, ‘Coronavirus Puts Europe’s Solidarity to the Test’. Www.Euractiv.Com (blog), 6 March 2020. https://www.euractiv.com/section/coronavirus/news/coronavirus-puts-euro….

(6) A. M Pacces and M. Weimer Alessio M., and Maria WEIMER. ‘From Diversity to Coordination: A European Approach to COVID-19’. European Journal of Risk Regulation, early view, April 2020. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/european-journal-of-risk-regula…

(7) A. de Ruijter, EU Health Law & Policy: The Expansion of EU Power in Public Health and Health Care. (Oxford: Oxford University Press), 2019.

(8) Kamkhaji. ‘Crisis, Learning and Policy Change in the European Union’.

(9) European Parliament, ‘Free movement of Persons’, February 2020. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/factsheets/en/sheet/147/free-movement-of…

(10) T. Deruelle, ‘Bricolage or Entrepreneurship? Lessons from the Creation of the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control’. European Policy Analysis, Vol. 2 (2) 2016, pp. 43–67.

(11) D. M. Trubek, M. P. Cottrell and M. Nance, “‘Soft Law,’ ‘Hard Law,’ and European Integration: Toward a Theory of Hybridity,” SSRN Scholarly Paper (Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network, November 1, 2005).

(12) S. L. Greer and M. Mätzke. ‘Bacteria without Borders: Communicable Disease Politics in Europe’. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, Vol. 37 (6) 2012, pp. 887–914.

(13) A. Damonte, C. A. Dunlop, and C. M. Radaelli, “Controlling Bureaucracies with Fire Alarms: Policy Instruments and Cross-Country Patterns,” Journal of European Public Policy, Vol. 21 (5) 2014, pp.1330–49.

(14) Greer, ‘Bacteria without Borders’

(15) de Ruijter, ‘EU Health Law & Policy’

(16) See Article 5 of Decision 1082/2013/EU on serious cross-border threats to health. https://ec.europa.eu/health/sites/health/files/preparedness_response/do…

(17) PWC, ‘Thrid External Evaluation of ECDC’, European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, September 2019. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/third-independ….

(18) ECDC, ‘Risk Assessment: Pneumonia cases possibly associated with a novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China’ ECDC, 9 January 2020. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/pneumonia-cases-possibl…

(19) J. Marques and V. Da Silva. ‘UK Is “2 to 3 Weeks” behind Italy, Says Disease Control Expert’, Euronews, 11 March 2020, https://www.euronews.com/2020/03/11/coronavirus-uk-is-2-to-3-weeks-behi….

(20) E. Oddone, ‘Italy Struggles with Virus “That Doesn’t Respect Borders”’, Al Jazeera, 26 February 2020. https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/features/italy-struggles-virus-doesn-….

(21) European Parliament, ‘Outcome of the video-conference call of EU Heads of State or Government on10 March 2020’, European Parliament, 13 March 2020. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document.html?reference=EPR…

(22) European Commission, ‘COMMUNICATION FROM THE COMMISSION TO THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT, THE EUROPEAN COUNCIL AND THE COUNCIL COVID-19: Temporary Restriction on Non-Essential Travel to the EU’, Eur lex COM(2020) 115 final, 16 March 2020. https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/communication-travel-on-the-…

(23) ‘Coronavirus : chronologie de la pandémie en Europe’, Toute l’Europe.eu, 21 May 2020. https://www.touteleurope.eu/actualite/coronavirus-chronologie-de-la-pan….

(24) R. Momtaz, ‘France Announces Stricter Coronavirus Confinement Rules’, POLITICO, 23 March 2020. https://www.politico.eu/article/france-announces-stricter-coronavirus-c….

(25) POLITICO, ‘What Should the EU Do about Hungary?’, POLITICO, 14 April 2020. https://www.politico.eu/article/what-should-the-eu-do-about-hungary-cor….

(26) R. Milne. ‘Sweden’s Death Toll Unnerves Its Nordic Neighbours’, Financial Times, 20 May 2020. https://www.ft.com/content/46733256-5a84-4429-89e0-8cce9d4095e4.

(27) F. Guarascio, ‘Europe Could Face More Drug Shortages as Coronavirus Squeezes Supplies’, Reuters, 5 March 2020. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-eu-idUSKBN20S1R2.

(28) Reuters, ‘Macron Says France Is There for Italy, Europe Must Not Be “Selfish”’. Reuters, 28 March 2020. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-france-italy-idUS….

(29) A. Tidey, ‘More French COVID-19 Patients Flown to Germany and Switzerland’. Euronews, 28 March 2020. https://www.euronews.com/2020/03/28/eight-covid-19-patients-flown-from-….

(30) European Commission. ‘Coronavirus Response’, web page, https://ec.europa.eu/info/live-work-travel-eu/health/coronavirus-respon…

(31) A. Renda and R. Castro. ‘Towards Stronger EU Governance of Health Threats after the COVID-19 Pandemic’. European Journal of Risk Regulation, early view, April 2020. https://doi.org/10.1017/err.2020.34.

(32) European Commission, ‘Joint European Roadmap towards lifting COVID-19 containment measures’ European Commission, 26 March 2020. https://ec.europa.eu/info/sites/info/files/communication_-_a_european_r…

(33) J. Henley and S. Jones, ‘Global Report: Madrid Told Not to Ease Lockdown as Italy Warns Rule-Breakers’, The Guardian, 8 May 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/may/08/global-report-spain-and-i….

(34) A. Wilson, Antonia. ‘Which European Countries Are Easing Travel Restrictions?’, The Guardian, 18 May 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/travel/2020/may/18/europe-holidays-which-eu….

(35) ECDC, ‘Rapid Risk Assessment: Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the EU/EEA and the UK– ninth update’, ECDC, 23 April 2020. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/rapid-risk-assessment-c…

(36) European Commission, Press Release, 13 May 2020. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_20_854

(37) A. de Ruijter, R. Beetsma, B. Burgoon, F. Nicoli and F. Vandenbroucke, ‘Give the EU More Power to Fight Epidemics’, POLITICO, 26 March 2020. https://www.politico.eu/article/coronavirus-eu-power-pandemic/.

(38) N. Chrysoloras, V. Dendrinou and A. Brambilla ‘Europe Widens Virus Lockdown, Moves to Limit Economic Damage’, Bloomberg.Com, 15 March 2020. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-03-15/europe-lockdown-spre….

(39) U. Puetter, ‘Introducing the Debate Section: “Who Leads the Euro Zone? From Crisis Management to Future Reform”’. Journal of European Public Policy, early view, April 2020, pp.1–6.

(40) K. Petroff and P. Skolimowski, ‘Lagarde Says Virus Not Yet at Stage Requiring ECB Response: FT’. Bloomberg.Com, 27 February 2020. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-02-27/lagarde-says-virus-n….

(41) J. Hirai and J. Ainger, ‘Investors Rush to Buy Europe’s Bonds After ECB Drops QE Limits’, Bloomberg.Com, 26 March 2020. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-03-26/investors-rush-to-bu….

(42) E. Zalan, ‘Commission Struggles with German Court Challenge’, EUobserver, 12 May 2020. https://euobserver.com/political/148329.

(43) T.P. Woźniakowski ‘Why the Sovereign Debt Crisis Could Lead to a Federal Fiscal Union: The Paradoxical Origins of Fiscalization in the United States and Insights for the European Union’. Journal of European Public Policy Vol. 25(4), pp. 630–49.

(44) L. Asscher, ‘Dutch “No” on Corona Bonds Undermines European Project’, POLITICO, 31 March 2020. https://www.politico.eu/article/dutch-no-on-corona-bonds-undermines-eur….

(45) D. M. Herszenhorn And H. Von Der Burchard, ‘Von Der Leyen Brands Corona Bonds a “Slogan” Setting off Firestorm in Italy’, POLITICO, 29 March 2020. https://www.politico.eu/article/von-der-leyen-corona-bonds-slogan-fires….

(46) European Commission, Press Release, 10 March 2020. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_20_440

(47) Eurogroup, Press Release, 9 April 2020. https://www.consilium.europa.eu/en/press/press-releases/2020/04/09/repo…

(48) European Commission, SURE, 2 April 2020. https://ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/economic-and-fiscal-pol…

(49) J. Rankin, Jennifer. ‘EU Leaders Clash over Trillion-Euro Covid-19 Aid in Online Meeting’, The Guardian, 23 April 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/apr/23/clashes-predicted-over-tr….

(50) P. Taylor, ‘Merkel’s Milestone Moment’, POLITICO, 19 May 2020. https://www.politico.eu/article/angela-merkel-milestone-moment-europe-c….

(51) ‘The Merkel-Macron Plan to Bail out Europe Is Surprisingly Ambitious’, The Economist, 21 May 2020. https://www.economist.com/europe/2020/05/21/the-merkel-macron-plan-to-b…;