The Syrian regime was not prepared security-wise or politically for the popular revolution seeking to overthrow it. The perceived dangers that the Syrian security services were formed for and are seasoned to confront are either political opposition groups or a few designated terrorist groups carrying out scattered operations such as assassinations or explosions. The outbreak of a broad-based popular revolution involving hundreds of thousands or more in various locations across the country was unimaginable to the political and security scope of these devices and the the regime itself. However, as an Arabic proverb professes, "danger comes where it is least expected," and indeed a popular revolution erupted in March of last year.

Violence and Hatred: An Explosive Amalgam

Facing a situation that was not part of its agenda, the regime positioned the Syrian army's units at the confrontation front, and employed shabbiha, i.e. organised thug gangs, giving them all orders to terminate the peaceful protest "by any means," as per a report issued by the Human Rights Watch in December 2011 attributed to a senior Syrian official believed to be Bashar al-Assad himself.

Indeed, the rebellious crowds were faced by extreme violence, accompanied by intense hatred and enmity towards all participants in the protests as shown in official statements and government media coverage. However, the approach of protest termination "by any means" has led to two outcomes: first, consecutive splits in the army, in small numbers at a time but amounting to a considerable number over the course of fourteen months. Second, the popular origination and psychological strengthening of opposition to the regime, as many civilians in many parts of the country joined the military dissidents and took up arms against the regime forces.

The mix of violence and hatred adopted by the regime in encountering protesters increased the anger and resentment of participants in the revolution as well as of a large segment of the non participating population. These feelings create the psychological ground that the revolution requires to continue. The protesters' chants, banners, and songs reflect the psychological barrier that separates them from the regime. Some of these chants and banners include strong expressions of contempt for President Bashar al-Assad and his father Hafez in polyphonic chants (including songs with Western rhythms), describing the regime as an occupier and the security and military forces as occupation forces or gangs.

It seems that the ongoing popular protests, with the transformation of forms and regions of outbreaks and without the slightest indication of cessation or decline in the near future, are due mainly to the Syrians' psychological and political liberation from the al-Assad regime of both father and son. Perhaps, an additional source for the continuity is the common perception that the regime's restoration of control (which is known through recent experience and history to be cruel and vindictive) would lead to another thirty years of humiliation and general corruption materially, morally and politically. This is a strong reason for what can be described as the psychology of burning bridges adopted by growing numbers of Syrians, reflected by the fact that some figures who appear on today's satellite channels from within the country do not hide their names and faces. They are indeed cautious in their movement but no longer withhold their identities, which was not the case at the beginning of the revolution.

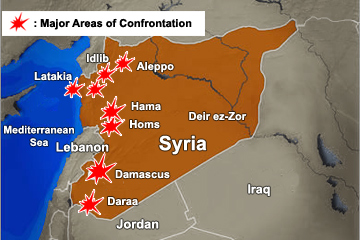

The factors that led to the continuity of the general public rebellion also include the expansion of the geographic and human base. Syrians and the world as a whole were acquainted with the names of a large number of cities, towns, neighbourhoods and villages that had been previously unknown and forgotten. A native of Daraa feels familiarity towards natives of Damascus, Douma, Baba Amr, and Baniyas as well as residents of occupied Kafranbel and Deir ez-Zor and university students from Aleppo, to name a few. The cities and towns honor each other, especially those that were subjected to the oppression of the regime's forces and feel a sense of solidarity that increases the internal isolation of the regime.

These factors – psychological and political estrangement, the disposition of burning bridges, and the expanding human and geographical base of the revolution – are the fundamental sources of its sustenance. The regime's failure to develop an approach not based on repression will add to the effectiveness of these factors.

This assessment also suggest that the variation of Syrian revolution's manifestations including armed resistance and relief networks that have helped in alleviating the suffering of as much as about a million internal refugees has contributed to granting the revolution immunity to the regime's strikes, and provided the resistance with energy and sustainability.

Excessive Expansion and Decreasing Funds

The regime's forces have prevailed all over the country and are likely to show signs of strategic over-expansion at any time, i.e. costs may exceed the assigned limits and thus the regime will be incapable of providing the required resources. Even if the regime continues to receive strong financial support from Iran, and perhaps from al-Maliki's government in Iraq, it cannot expect to be compensated for its losses for long. Monthly operations cost the regime about one billion U.S. dollars and the foreign currency balance today is estimated between five and ten billion dollars (whereas before the revolution it was twenty billion dollars) as stated in an article in The Washington Post. Some analysts argued that allowing the shabbiha and security forces into the properties of civilians, thus facilitating the emergence of markets for stolen property in some of Homs's pro-regime districts, is an indicator of the regime's declining ability to finance this war.

Reflecting the continuing momentum of the Syrian revolution, this view contradicts with the tone of distress of some local speakers on behalf of the revolution in many locations in the country, and with the approach of politicians outside Syria who speak on behalf of the revolution. Their statements lay the odds on the use of distress to mobilise international support against the regime. However, they may give the wrong impression about the revolution's potential to continue unlike an overview of the revolution throughout the whole country over more than 400 days that suggests that the revolution will continue with renewed determination, and that it will not stop to diversify and combine the means of resistance.

The revolution, thus, should not be evaluated from a narrow perspective from within the country or an ideological perspective from within or outside it. There are certainly high human and material costs of sustaining the revolution. There is also no doubt that the resulting pain is severe, which gives the impression that the revolution is being strangled, and reveals alarm in speakers' tones. However, protests that are attacked here or there remerge in many other areas, including subdued areas on which the regime loosened its grip; and this has occurred time and again.

Indeed, the regime could not put out all fires at the same time and therefore it seems that the outbreak of too much of them is an important element in the strategy of the Syrian revolution. The protests actually seem to be increasing.

Accordingly, occasional factors such as the Arab observers that went to Syria at the end of 2011, or international observers that went in April 2012 have had no significant effect. Such factors could have resulted in a temporary decrease of the number of victims, and thus prove to be a source of a relative and temporary protection for some regions. However, in both cases, the number of observers and their instruments and authorisation were not sufficient to make a significant difference. This does not eliminate the efficiency of Arab or international observation, contrary to the general outlook of the revolution's local spokespersons or some politicians. A third party is important for if it does not contribute to the reduction of the regime's aggression and save some souls, it will at least provide a testament to the Syrian revolution and against the regime.

Unlike many revolution and opposition forces, the regime is the only party that deals with the crisis it encounters from a perspective that takes into account the whole country, and that was probably formed by the accumulated experience of its agencies during the revolution after authorities allocated resources and major forces including the military, intelligence, adminstration, Baathists, and shabbiha, as was leaked in "crisis management cell" documents.

However, the intellectual and moral limitedness of the regime's political strategists as well as their political extremism resulted in a limited overview. They thus failed to crush the revolution despite the resources and forces available to them, which the revolutionaries lack.

Strategy of Attrition

After more than a year of frequent talk of the crisis being "over" though it is not, how might the Syrian regime deal in the upcoming period with this fateful threat?

There is no doubt that the backbone of its plan will remain encountering revolution with violence for the point of its strength is that it monopolises the means of violence. Otherwise, it will inevitably be defeated and hence will not abandon this great privilege. Despite the declared commitment to the Annan plan, in actuality, there is nothing but negation of it; and the history of the regime does not indicate that it will adhere to its pledge to its citizens. However, it will exert its utmost effort to show that there is another party who is not committed to the plan by directing attention to what it calls "dirty operations" attributed to "armed terrorist gangs", described recently as "blasphemous." Nevertheless, there is great suspicion about the bombings that took place in recent months, mainly on Fridays. Even if the people are not convinced with its narrative, through these operations the regime will provoke the fear of losing public security – which may lead sectors of the population to blame the revolution and yearn for the old days of "safety and security."

The regime will also take on "the process of comprehensive reform" whose real content is just some formal procedures that do not affect the regime in any way, i.e. the political security composition, or the Assad family, intelligence services, elitist military units that primarily protect the regime from the people (the Republican Guard and the Fourth Armored Division). Among these formal procedures were the parliamentary elections on 7 May 2012, which were preceded by a new constitution and referendum at the end of February 2012. The overall purpose is to imply that political reforms are taking place and those who insist on the revolution have other undeclared goals targeting Syria's role in resistance. However, the domestic effectiveness of this dynamic is very limited though the Russians and other allies promote it as a genuine political process.

The regime will also attempt to take advantage of the divisions among the opposition, feeding them behind the scenes. This is an increasingly important factor in its policy, utilising the Annan initiative that provides for the launch of a political process that brings together the regime and the opposition and exploits the Arab League's apparent interest in unifying the Syrian opposition.

Nonetheless, a combination of uncontrolled violence, intimidation, and "reform" for over a year produced nothing, and there is no reason to believe that it will in the future. Playing with the opposition's contradictions could be more productive due to the opposition's complex differences and inability to develop an vision of the Syrian situation today and the new Syria. In any case, the opposition's problems have always had limited influence on the course of the domestic protest movement.

Within the regime's explicit policy, there is an implicit policy, so to speak, provoking divisions in the Syrian society, turning Syrians of different orientation against each other, and making the Syrian crisis a chronic internal crisis and source of complex and multi-front regional conflict with perplexing complications and high costs. However, this strategy overloads the regime with burdens and costs that increasingly limit its ability to take action. The target of the domestic part of the implicit policy is to reduce the opposition camp in order to defeat it more easily, while the aim of the regional part is to expand the camp of potentially affected parties to make reconsider confronting it. Both parts are oriented toward winning the great battle of who will rule Damascus and how it will be ruled.

Strategic Patience

The continuation of the status quo is now more likely The regime cannot and will not be able to stop the momentum of the strong and multi-source popular rebellion. However, although the regime seems to ready to play all its cards in the confrontation, the rebel strategy is based on patience, coordinating relations between the components of the revolution, more flexibility in the movement of the military component, and providing material assistance to the most affected groups. This strategy will be helpful in fueling popular opposition until the regime falls apart from within, and perhaps with the assistance of more favourable regional and international circumstances.