|

|

A foreign hostage was among seven seized in Niger by an al-Qaida offshoot, according to a group that monitors terrorism. [AP] |

| Abstract

This report argues that Al-Shabaab’s decision to attack the Westgate Mall at the heart of Nairobi, where local and international media networks can easily stream live coverage of the siege coupled with the In Amenas-like hostage situation points to the group’s strategic intention to create a scene that will drag for long, to serve its propaganda that its capacity has not been significantly degraded. |

Introduction

Although terrorism is not new in Africa, the renewed capacity of Africa’s terrorist groups to successfully plan and mount audacious local and transnational attacks is a worrisome trend that African states and the international community must urgently and collectively respond to. The January 2013 siege at the In Amenas gas plant in Algeria was the first to dominate headline news this year. On 16 January 2013, militants of Al-Mulathameen Brigade (The Masked Brigade" or "Those Who Sign with Blood") founded by a veteran jihadist, Mokhtar Belmokhtar, took hundreds of workers hostage at the gas plant. The four-day siege ended when Algerian forces invaded the plant, resulting in heavy human casualties. In total, 685 Algerian workers and 107 of the 132 foreigners working at the plant were freed, while 37 hostages and 32 terrorists were killed.

The 21 September 2013 attack at the Westgate Premier Shopping Mall in Nairobi, Kenya, has added to the growing concern over terrorism and transnational jihadism in Africa. The Somali-based Al-Shabaab, a group with ties to al-Qaida, claimed responsibility for the attack. This report briefly examines the considerations that informed the choice and timing of the attack on the Westgate Premier Shopping Mall, and extrapolations that could be made from the attack.

The Westgate Attack

The 21 September Westgate attack did not come as a surprise to many observers given the repeated warning by Al-Shabaab that it will attack Kenya for its military incursion into Somalia. (1) The Al-Shabaab had in the past made good such threat, when on 11 July 2010 it staged twin bombings of two groups of soccer fans watching the World Cup games, in Kampala, Ugandan, killing about 79 people and injuring may others. The strike, its first on foreign soil by Al-Shabaab, was launched to punish Uganda for contributing the bulk of African peacekeeping force in Somalia. After that attack one of Al-Shabaab’s leaders, Mohamed Abdi Godane, also known as Abu Zubayr, enthused that “What happened in Kampala was just the beginning”. (2) Therefore, the Westgate attack came against this backdrop.

Over the past two years, Al-Shabaab had mounted dozens of smaller-scale strikes in Kenya for its involvement in Somalia, targeting churches, nightclubs and bus stations. Many were focused in towns along the Kenya-Somalia border, but the campaign has included strikes in Mombasa and Nairobi. For example, two attacks on a Nairobi bus station and on Mwaura's Bar on October 2011 which killed one person and wounded more than 20 was blamed on the Al-Shabaab. Kenya also blamed Al-Shabaab for grenade attacks that killed at least six people at a Nairobi bus station on 10 March 2012.

The Westgate assault marks a return of Al-Shabaab’s audacious transnational jihadism. The attack which lasted for four days began around noon on Saturday 21 September, when allegedly 10 to 15 gunmen stormed the packed five-story building, shooting and hurling grenades at shoppers and staff. The attackers were allegedly targeting mostly non-Muslims, intended to communicate to impressionable muslin minds that it is actually protecting Muslims while engaging in Jihadism.

The attackers were mostly in civilian clothes, but a few donned camouflage fatigues. Some carried sophisticated machine guns, and others wielded AK-47 rifles. (3) Kenyan security forces responded to the siege by launching an assault on the mall to kill the militants and rescue several hostages and shoppers hold up in the mall. The attack ended on Tuesday, 24 September when Kenyan troops detonated explosives to get through locked doors inside the mall as they searched for militants or booby traps.

By the time the four-day bloody siege ended, at least 67 civilians, six security officers and five suspected terrorists were reported dead. About 18 foreigners were among the dead, including six Britons, as well as citizens from France, Canada, the Netherlands, Australia, Peru, India, Ghana, South Africa and China. Over 175 people were injured, including five Americans. Nine other suspected terrorists were taken into custody by Kenyan forces. Some of the attackers are believed to have escaped through a sewage canal that security forces discovered 72 hours after the attack began, while others may have escaped during the mayhem, disguising as civilians.

The exact number and identity of the attackers involved in the sophisticated assault remain unclear and at best speculated on. Amidst the mayhem, however, Al-Shabaab posted on one of its twitter accounts the names and nationalities of 9 of the alleged attackers (see table 1). Shortly after posting the information, Twitter suspended the Al-Shabaab’s account, making it the fourth time an Al-Shabaab account will be short down in the course of the Westgate attack.

Table 1: The Names and Nationalities of the Westgate Attackers Released by Al-Shabaab

|

S/No |

Name | Age |

Country |

| 1 | Ahmed Mohamed Isse | 22 | (Minnesota) USA |

| 2 | Abdifatah Osman Keynadiid | 24 | (Minneapolis) USA |

| 3 | General Mustaf Nuradin | 27 | (Kansas City) USA |

| 4 | Qasim Said | 22 | (Garissa) Kenya |

| 5 | Ahmed Nasir Shirdon | 24 | United Kingdom |

| 6 | Zaki Jma’a Arale | 20 | (Hargeisa) Somalia |

| 7 | Ismail Guled | 23 | Finland |

| 8 | Siad Nuh | 25 | (Kismayu) Somalia |

| 9 | Abdirazaq Mowlid | 24 | Canada |

Although the authenticity of the number and nationalities of the attackers are yet to be confirmed, analysts are increasingly concerned that Al-Shabaab is able to recruit members from other countries, including Western countries, for its operations. This has accentuated fear that Al-Shabaab can leverage on such penetration to inspire future ‘lone’ or coordinated attacks outside Somalia.

Why Al-Shabaab attacked a Nairobi Mall

While claiming responsibility for the attack on Twitter, Al-Shabaab claimed the attack was "retributive justice for crimes committed" by Kenya's military in Somalia. It will be recalled that on 16 October 2011, Kenya Defence Forces (KDF) moved into Southern Somalia to pursue Al-Shabaab fighters after a series of attacks and kidnapping of tourist in northern Kenya near the Somali border.

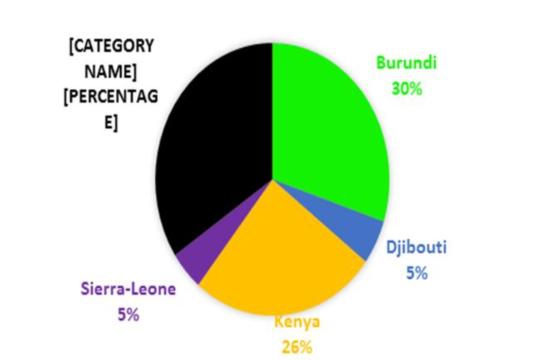

For the African Union (AU), the entry of KDF and subsequent quick gains was a game changer in the search for stability in Somalia. The AU subsequently requested of the Kenyan government that the KDF be integrated into AMISOM, including incorporating its objectives within the AMISOM mandate. (4) The legal requirements for rehatting were followed, and the KDF in Somalia were later formally integrated into AMISOM on 22 February 2012 after the United Nations Security Council passed Resolution 2036. The Resolution also increased AMISOM force level from 12, 000 to 17, 731. As shown in table 2, Kenya is one of the five troop contributing countries (TCCs) to the African Union Mission in Somalia (AMISOM) that since 2011 has forced Al-Shabaab to retreat from the Somali capital, Mogadishu, as well as other strongholds. The KDF accounts for 26% of AMISOM forces.

Table 2: Troop Contributing Countries (TCCs) to AMISOM

|

S/No |

TCCs |

Commencement Date |

Number of Troops |

| 1 | Burundi | December 2007 | 5,432 |

| 2 | Djibouti | December 2011 | 960 |

| 3 | Kenya | February 2012 | 4,652 |

| 4 | Sierra-Leone | April 2012 | 850 |

| 5 | Uganda | March 2007 | 6,223 |

The intervention of the KDF in Somalia, particularly its success in driving out Al-Shabaab out of Kismaayo, a strategic port city, amounted to the strangulation of Al-Shabaab’s lifeline. When Al-Shabab lost Kismaayo, it lost its hold on profits from imports and exports through that harbor. The export of dates, bananas, sheep, and goats provided millions of dollars in annual tax revenue for Al-Shabab, as did imports of consumer goods. (5)

Percentage Distribution of Troop Size of the AMISOM

|

Therefore, the Westgate attack was as an aggressive reponse by Al Shabaab for the squeezing of its wind pipe by Kenyan forces. The attack on Westgate mall again further proves Al-Shabaab’s capability to launch deadly attacks outside its traditional Somali borders, especially targeting TCCs to the AMISOM.

The 21 September Attack in Perspective

From analytical point of view, the choice and timing of the attack on the Westgate mall show that the Al-Shabaab had spent months planning the attack to guarantee its success. The choice of the Westgate could be informed by three critical interrelated considerations. First is to pick out a soft target that is popular with foreigners and affluent Kenyans. In the event of successful planning and execution of the attack, Al-Shabaab is convinced that it fighters will kill several foreigners, especially westerners.

Second, and as a corollary to the above, was the desire to hit at the upper class of the Kenyan society. Given that such upscale place is well frequented by affluent Kenyans, Al-Shabaab strategists would have considered it one of many high-profile targets that has the right mix of victims (relative of Kenyan politicians, businessmen etc), whose eventual death will help swell the ranks of influential persons that would pressure the Kenyan government to withdraw its troops from Somalia. For its part, Al-Shaabab is hoping that the Westgate attack will convince Kenyans that a sustained involvement of the KDF in Somalia is just too risky and unrewarding a venture.

Third, because of the high-profile nature of the mall, the external operations arm of the Al-Shabaab must have considered it a worthy target that will attract the right level of local and international media attention that will help bolsters its image in the ranks of global jihadism. In this wise, the attack was planned to be more in the form of selective killing and hostage-taking rather than a suicide bombing that loose media coverage once the bomb goes off and security forces seal off the place. That the siege took place at the heart of Nairobi where local and international media networks can easily stream live coverage of it coupled with the In Amenas-like hostage situation points to the fact that Al-Shabaab wanted to create a scene that will drag for long, to serve its propaganda that its capacity has not been significantly degraded.

Also, the decision to strike during weekend is not difficult to fathom. It is obvious that Saturdays are when the mall entertains the highest number of shoppers or visitors, thereby enhancing the chances of inflicting maximum damage and destruction (killing several people of different nationality). The success of the Westgate attack reveals intelligence failure on the part of Kenyan security and intelligence community, not to mention the accusation of pilfering at the mall blamed on Kenyan security forces involved in dislodging the terrorist. (6) Among the immediate consequences of this failure are huge death tolls, loss of valuables, and dent on Kenyan tourist industry.

Responses to the Westgate Attack

The Westgate attack has triggered actions by some states that are directly or indirectly affected by the attacks. Countries that have troops with AMISOM such as Sierra Leone and Uganda have recently rejig their national security architecture, including tightening borders security, scaling up internal surveillance and beefing routine patrols. The attack has equally forced the US to begin to re-assess its estimation of the capability of the Al-Shabaab to directly hit American targets, or work with its sympathisers to mount attack on American soil. The US approach had previously been limited to the occasional drone strike or raid when a particularly high-value al-Qaida target comes into view, while relying primarily on assisting Somali transitional Federal government and AMISOM to carry out the day-to-day fight against Al-Shabaab. With the mall attack, the approach may change dramatically to one of increased targeting of Al-Shabaab commanders and strategists, as evident in the failed attempt by US Navy Seal team to capture or kill a top Al Shabaab leader, Mukhtar Abu Zubeyr, in a pre-dawn attack at his seaside villa in the Somali town of Baraawe, south of Mogadishu. (7)

Extrapolations from the Westgate Siege

The Westgate attack should serve as a wake-up call to African states, particularly those with troops in Somalia, to urgently move from complacency to high-level security awareness in anticipation of such attacks on their soil or even their diplomatic posts and strategic interests elsewhere in Africa. Burundi, Djibouti and Sierra-Leone are the only TCCs to AMISOM that Al-Shabaab has not staged attacks on their soil. These states are most likely in the hit list of Al-Shabaab. The order they are listed is not known, and when such attacks will happen will depend largely on the resources, planning and timing of Al-Shabaab’s strategists. It will equally depend on the success or failure of the international community to neutralise Godane and fellow hardliners.

What seems clear is that intelligence-driven targeting of Al-Shabaab’s strategists and fighters will deny it the comfort of planning and executing such attacks, and the maintenance of high-level of security awareness by the potential states will save them of such ‘embarrassment’ by transnational jihadists. What is needed to prevent this from happening in Africa or elsewhere in the world is the commitment (will and resources) of the international community to fast-track the rebuilding of the failed Somali state, while bolstering the capacity of African states to eliminate the drivers of violent extremism and terrorism through robust governance reform initiatives.

Conclusion

One thing that the Westgate attack made clear is that transnational jihadist will continue to target those who they consider as ‘enemies’ irrespective of their location. The staging of attacks by Al-Shabaab in 2010 in Kampala did not compel the Ugandan government to pull out its forces from AMISOM. It is almost certain that the Nairobi attack will not deter the Kenyan government. If anything, Kenya will be more determined to crackdown on the group and its Kenya-affiliate, the al Hijra. But it needs to do this in a robust and measured way, to avoid indulging in misguided policies and (re-)actions that could lead to further radicalisation of Kenya's Somali and Muslim communities, thereby creating more home-grown terrorist from the womb of the Westgate attack. In view of allegations of intelligence failure and involvement of security forces in theft at the mall, the professionalization of Kenyan security forces should be part of President Uhuru Kenyatta’s counter-terrorism priorities.

___________________________________

*Dr Freedom C. Onuoha is a Research Fellow, Centre for Strategic Research and Studies, National Defence College, Abuja, Nigeria.

Endnotes

(1) G. Joselow, (2011) “Grenade Attack in Kenya Follows Threats From al-Shabaab”, VOA, 23 October, http://www.voanews.com/content/grenade-attack-wounds-13-in-kenya-132429548/147096.html

(2) AFP, (2010), “Uganda Bombings, ‘Just the beginning’”, ABC News, 15 July, http://www.abc.net.au/news/2010-07-15/uganda-bombings-just-the-beginning/906350

(3) S. Raghavan, (2013) “Gunmen who stormed Kenya mall reportedly spoke English, were from different countries”, Washington Post, 23 September, http://www.washingtonpost.com/world/africa/explosions-gunfire-at-kenyan-mall-as-armed-attack-enters-3rd-day/2013/09/23/b0b558be-2442-11e3-b3e9-d97fb087acd6_story.html

(4) C. Oguna, (2012) “Assessing Operation Linda Inchi”, Africa Defence Forum, Vol. 6, No.2, p.40

(5) R. Rotberg (2013) “A wounded leopard: Why Somalia’s al-Shabab attacked a Nairobi mall”, 23 September, http://www.theglobeandmail.com/commentary/a-wounded-leopard-why-somalias-al-shabaab-attacked-a-nairobi-shopping-mall/article14460642/

(6) Associated Press, (2013) “Mall Shopkeepers Suspect Kenyan Troops In Thefts”, 30 September, http://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=227709383

(7) I. Johnston & A. Withnall, (2013) “US Navy Seal Team fails in attempt to kill al-Shabaab leader in Somalia raid following Nairobi mall Attack”, The Independent, 6 October, http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/africa/us-navy-seal-team-fails-in-attempt-to-kill-alshabaab-leader-in-somalia-raid-following-nairobi-mall-attack-8860808.html