The November 2016 loan agreement between Egypt and the IMF will provide Cairo with another temporary economic life line. Yet, as with previous loans in Egypt’s long history of international financial assistance, the current agreement reflects not only economic considerations, but also the political priorities of multiple global and regional actors. This report argues that, since the popular uprising of 2011, the priorities of key actors—including the IMF and the GCC states—have been at odds, thus preventing any actor from securing their objectives in Egypt and the region. The article forecasts that Egypt’s reliance on financial aid will continue due to the impact of three regional trends on Egypt’s foreign currency deficit. (1) Amid lower oil prices, GCC countries are increasingly shifting away from expatriate labor in certain sectors, thus reducing Egyptian remittances. (2) Recent discoveries of Egyptian natural gas will not be developed in time to off-set the growing costs of energy imports. (3) Despite the doubling of Suez Canal capacity, transit revenues remain flat due to depressed international trade volumes. The paper concludes by arguing that, despite otherwise conflicting priorities, the risk of Egyptian instability should compel the GCC, the US, and the IMF to seek a grand bargain and play a joint gatekeeper role that ensures long-term political and economic stability in Egypt.

Introduction

The International Monetary Fund approved a $12 billion loan to Egypt in November 2016. The approval comes at a time when Cairo’s relations with Riyadh, its key financial and diplomatic supporter, have come under significant strain due to differences in responding to regional crises in both Yemen and Syria. The decision to take on the IMF as creditor comes at a significant social cost and political risk. The difficult loan conditions have required Cairo to, among other measures, introduce a value-added tax, remove petroleum and electricity subsidies and remove exchange rate controls that have devalued the Egyptian pound by almost 50 per cent. Egypt imports many essential goods like refined petroleum, wheat, rice, sugar and medicines. The devalued currency will exacerbate soaring inflation at a time that subsidies are being rolled back and taxes are being reduced. Aware of the potential of this loan agreement to ignite social protest against the government, security forces had been deployed across the country when it was publically announced.

Economic factors leading to the IMF loan agreement

The Egyptian economy has experienced continual decline since the global financial crisis of 2008, a situation that was exacerbated by the fallout from the popular uprising in 2011. A key economic weakness during this period has been a shortage of foreign currency.

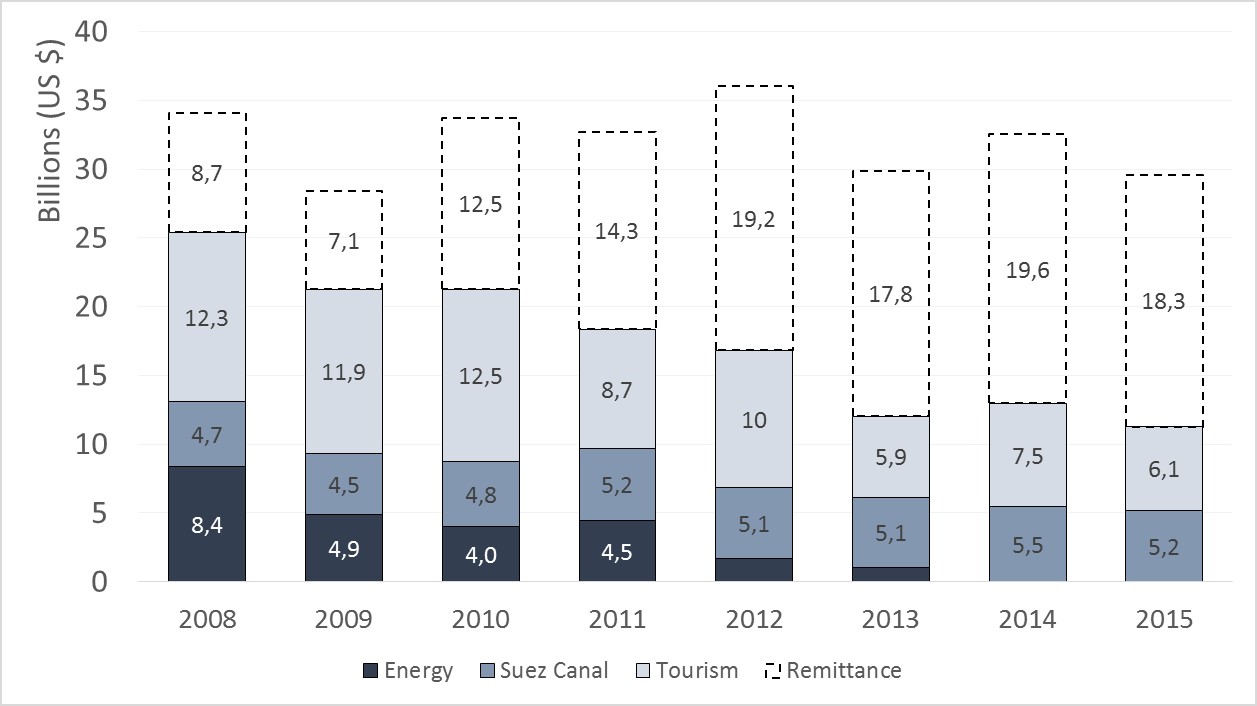

During this period foreign currency exchange from Egyptians working abroad have been a significant support to the economy. These remittances—mostly coming from Egyptians working in GCC states—were the largest source of foreign currency revenues, increasing from $8.3 billion in 2009 to $18.3 billion in 2014 (see figure 1). However, the precipitous drop in global oil prices since 2014 has hobbled GCC economies, making it unlikely that Egyptian remittances will continue on their current trajectory.

|

| Figure 1: Foreign Currency Received from Egyptians Working Abroad |

Since 2011, Egypt’s shortfalls in foreign currency have been supplanted by approximately $38 billion in loans from GCC states. This external financial support has been critical to offset the decline or stagnation in three of Egypt’s critical foreign currency earning sectors (see figure 2).

|

First, lucrative energy exports, which earned Egypt $8.4 billion in 2008, have been eliminated as the country transitioned from being a net exporter to net importer by 2014. This energy transition resulted from high population growth, an increasingly urban population, energy subsidies that permitted wasteful usage, and the decline of local production. While the recent discovery of natural gas deposits off Egypt’s north shore is expected to return Egypt to its former position as a net energy exporter, this is unlikely to occur in the short to medium term. The government’s official timeline for transitioning back to a net energy exporter is 2021.(1) This timeline may be extended should rising local demand and the natural decline of older fields require export volumes to be diverted for local consumption. Further, significant international discoveries of natural gas elsewhere could suppress profit margins and make it unlikely that natural gas will be able to provide the same level of support to the economy as oil production has done in the past.

Second, revenue from the Suez Canal remains relatively flat at approximately $5 billion per year. This is despite the government’s investment of $8.2 billion to double the capacity of the canal. Traffic through the canal still remains 20% below 2008 levels due to depressed international trade. Rather than a signal of Egypt’s economic return, the canal expansion project has been an indicator of poor planning and wasteful expenditure on the part of government.(2)

Third, tourism, which was the largest foreign currency earner in 2008 ($12.3 billion), has been undercut by increased violence in the wake of the 2013 military coup. Earning only $6.1 billion in 2015, tourism revenues fell even further following the suspected terrorist attack on a flight carrying Russian tourists over the Sinai.(3)

Therefore, while the IMF deal is linked to economic reforms, it is unlikely that these reform measures will overcome the decline in sectors that have been critical to providing foreign currency. At the same time, the interest payments on such loans will consume an increasing portion of the government’s budget in the years ahead.

Egypt’s historical relationship with the IMF

The historical relationship between Egypt and the IMF demonstrates that Cairo has frequently managed to avoid implementing difficult economic reforms and successfully negotiate the cancellation of its foreign debt. The relationship dates back to the 1960s, however the 1977 loan agreement marked a significant turning point when the Egyptian public rioted against IMF-imposed food subsidy reforms. The Egyptian government eventually retracted these reforms, leading to the collapse of the loan agreement and Cairo turning instead to direct US aid to manage the shortfall in foreign exchange reserves.

A decade later, in 1987, Egypt was again facing down international creditors as the government was unable to honor its $7 billion debt owed mostly to European creditors. The Paris Club, which represented the European creditors, required that any debt rescheduling be conditional upon Egypt securing a $1.5 billion loan from the IMF. By using the IMF as the gatekeeper to debt rescheduling, the Paris Club was able to incentivize economic reform. The IMF insisted on reform measures being implemented prior to the receipt of loan disbursements, while Egypt insisted that a gradual approach was required. A deadlock in negotiations led to the breakdown of the IMF gatekeeper role as Egypt was ultimately able to secure debt rescheduling through bilateral negotiations with its creditors.

Four years later, in 1991, Egypt was again unable to meet its commitments to foreign creditors. This time Egypt was in a significantly weaker negotiating position as the inability to meet foreign creditor obligations was not the only concern. The country faced a wheat shortage and needed foreign currency to import the shortfall. Compounding the situation, the World Bank suspended urgently needed loans to fund the expansion of electricity generation. Realizing Egypt’s weak position, the US and Germany suspended further aid until an agreement with the IMF could be reached. The IMF proposed a comprehensive reform package and demanded immediate implementation of reform measures prior to disbursements. When it seemed that Egypt would be forced to capitulate, outside events suddenly changed the dynamics of the negotiation; Egypt’s position quickly strengthened with Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait. To legitimize its intervention in the conflict and limit foreign support for Iraq, the US relied on Egypt joining the coalition. To gain Egypt’s support, the US was instrumental in securing debt cancelation. The US itself cancelled $7 billion, arranged for a $7.7 billion cancellation from Gulf states, and further arranged for the Paris Club to cancel the majority of its $27 billion debt. The Paris Club insisted on an IMF package; however, Egypt managed to secure debt cancellation for most of this debt without implementing many of the IMF reform requirements. When the war concluded, Egypt had successfully managed to cancel all its international debt except for $4 billion that remained with the Paris Club.

The 1991 debt relief enabled the growth of Egypt’s foreign exchange reserves, placing Cairo in a stronger negotiating position for the 1993 agreement with the IMF. The IMF and the Paris Club used debt relief for the remaining $4 billion as an incentive for economic reforms linked to an IMF credit facility. Egypt implemented a number of these reforms, but did not accept currency devaluation or the privatization of certain national industries. The agreement ultimately failed and the debt cancelation was not implemented. However, three years later in 1996, the Egyptian government had again exhausted foreign exchange reserves through poorly executed projects. The IMF executive board intervened, criticizing its staff members for being inflexible regarding requirements for currency devaluation. Devaluation was hence dropped from the requirements and cancellation of the $4 billion Paris Club debt was granted.

In the fifteen year period from the 1996 debt cancelation to the 2011 popular revolution, Egypt was able to manage its foreign exchange without IMF intervention or significant international aid. This was primarily due to high tourism revenues and increased oil exports. Production levels of crude oil remained close to peak levels during the 1990s and declining production during the 2000s was offset by unprecedented increases in the global oil price.

The historical precedent set during the period from 1977 to 1996 indicates that the IMF played a gatekeeper role for international loans and sought to protect the interests of western donors who, compared to the IMF, had provided the overwhelming majority of funds. However, these donors were ultimately compelled to cancel approximately $42 billion of Egyptian debt due to regional geopolitics and leniency from the IMF executive board.

Geopolitical factors behind recent international aid

The political transition that followed the 2011 overthrow of President Hosni Mubarak was characterized by a number of important dynamics that would form the framework to later loan negotiations. Following the closely-contested election of Mohamed Morsi, the interim military government undermined the new president by holding on to legislative powers until a new constitution was adopted and parliamentary elections were held. In the drafting of the new constitution, President Morsi was accused of appointing too many Islamists to the constituent assembly, angering opposition and minority groups. The new constitution was ultimately approved after Morsi undermined the judiciary through a decree that prevented their intervention in the drafting process.

Despite the consolidation of political power, a faltering economy had drained foreign exchange reserves, requiring the government to urgently seek foreign aid to prevent the collapse of the government. In the immediate aftermath of the election, the Morsi administration entered negotiations with the IMF to receive a $4.8 billion loan that would provide the international confidence required to secure the full loan, estimated to be $14.5 billion. However, despite agreeing on economic reform measures, the IMF did not want to disburse the first installment until the new constitution was drafted and a representative parliament was formed that could ratify the loan agreement. From the IMF perspective, the pressure to receive the loan would hasten the government to reach a compromise with opposition groups and only then would the loan agreement have the legitimacy of an elected parliament. However, the IMF was unable to effectively force this political compromise due to periodic loans from Qatar that totaled $8 billion. Critics have argued that Qatar effectively allowed the Morsi government to prolong a dangerous division between Islamist and non-Islamist groups. However, others have noted that Qatar provided large amounts of aid both before and after the elections, signaling its support of the political transition rather than any particular group. Further, it could be argued that Qatar’s support gave the new government time to engage with opposition groups such as the secular liberal group, who were in any case largely opposed to entering an agreement with the IMF.

Qatar’s actions were not only causing tension within Egypt. Qatar’s broader support for the Arab Spring unsettled the regional powers of other GCC countries who feared a wave democracy would upset the political order within their own countries. Thus, following the overthrow of the Morsi government in August 2013, Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Kuwait pledged $12 billion of unconditional support to the new military administration led by Abdel Fattah el-Sisi. This financial aid is estimated to have reached approximately $30 billion since the coup.

The Sisi government, however, has frustrated its GCC backers by its unwillingness to follow Saudi political leadership. Cairo’s tepid support for the Saudi-led war in Yemen, for example, has been an ongoing cause for concern in Riyadh. But Egypt-Saudi tensions rose significantly when Egypt diverged from Saudi policy on Syria, most notably when Egypt supported a Russian-drafted UN resolution that was seen to lend cover to the Assad regime’s assault on Aleppo. Egypt’s perceived support for the Iranian-backed Assad angered Riyadh to the extent that it canceled significant portions of financial aid in the form of central bank guarantees and subsidized oil shipments.

Despite displeasure with Egypt, Riyadh is discovering the limits of its leverage. The availability of IMF loans means that Riyadh is not able to subdue Cairo with threats of withdrawing financial support. From Cairo’s perspective, the social backlash of implementing IMF reforms is a price it is willing to pay to assert itself as an independent regional player.

For the IMF, the willingness to support the Sisi government represents an about-face in its Egyptian policy from just three years ago when it sought to force political reconciliation. Lending support to the Sisi government while it violently oppresses political opposition and engages in other human rights abuses stands in stark contrast to prior IMF requirements of securing broad political consensus before disbursing a loan to the Morsi government.

As such, none of Egypt’s principal financial donors have been able to achieve their original objectives with respect to financially supporting Egypt. Qatar’s support of a democratic Egypt has been undermined by other GCC states. The IMF, initially undermined by Qatar, has been unable to secure broad political support for its recent loan agreement. Finally, Saudi Arabia’s success in reversing the Arab Spring has led to Egypt becoming a strategic liability in countering rising Iranian influence within the region.

Conclusion

The global actors that financially support Egypt should consider the historical precedent of the 1977-1996 period and recognize that Egypt may not be able to repay its international debt nor maintain commitments to economic reform. Roughly $42 billion dollars of debt was accumulated and cancelled during this period. These actors must also consider the post-revolution precedent that financial aid does not carry a guarantee that Egypt will support lenders’ geopolitical objectives. These risks arise from the fact that Cairo has been able to play one lender against another due to their divergent objectives.

With the decline of its key foreign exchange sectors set to continue over the short to medium term, financial assistance to Egypt is likely to continue and increase over time and no single actor will have the capability to support Egypt alone. Hence, to mitigate the financial risk of debt default and ensure regional stability, these actors should enter a grand bargain that outlines common objectives for international financial support of Cairo. For such a grand bargain to be effective, it should have five main pillars.

First, financial aid must be linked to Egyptian political reform and respect for human rights. Reconciling Egypt’s various political factions is a precondition for reducing violence, which in turn will allow the tourism sector to rebound and help alleviate the foreign exchange crisis. Second, such political reform must be conditioned upon Cairo establishing a new constituent assembly that does not marginalize minority groups and prevents the military from intervening in the drafting of a new constitution. This requirement would in fact be same condition imposed by the IMF during the term of the Morsi government. However, the chances of success would be higher should all donors agree not to undermine the process through bi-lateral aid. Third, to address the risk of social upheaval, the IMF must commit to a program that phases in reforms over multiple years to minimize the impact on the poor. Fourth, all actors must be sensitive to the fact that pursuing such objectives in Egypt could foment a radical upheaval of GCC states’ own political orders, which is not in the interest of a region that is already in turmoil.

Since the 2008 global financial crisis and the Arab Spring, GCC countries have been responding with their own local programs for economic and social reform. Saudi Arabia in particular has been praised by the IMF for the “appropriately bold and far reaching” Vision 2030 plan that will include subsidy cuts, tax rises, sales of state assets, a government efficiency drive and efforts to spur private sector investment. These external pressures that are forcing the GCC to reconfigure their own social contracts should be respected as sufficient to ensure gradual positive reform that will not further destabilize the region. Fifth, expectations for Egypt to assist in regional conflicts should be lowered. This will prevent Cairo from becoming further entangled in contentious regional politics and instead allow the government to focus on domestic issues.

In Egypt, a government that is stable and enjoys broad political legitimacy is far more valuable to global actors than an unstable country that is prone to coup attempts or changes international alliances depending on who is willing to provide the next tranche of financial aid.

(1) Sarah Diaa, "Devaluation of Egyptian pound to help energy industry,” Gulf News, 8 November 2016, http://m.gulfnews.com/business/sectors/energy/devaluation-of-egyptian-pound-to-help-energy-industry-1.1926292

(2) Ahmed Feteha, “Egypt Shows Off $8 Billion Suez Canal Expansion That the World May Not Need,” Bloomberg, 4 August 2015, www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2015-08-04/egypt-shows-off-8-billion-suez-canal-gift-world-may-not-need

(3) "Egypt tourism losses in FY 2015/2016 the worst in 15 years: finance minister,” Aswat Masriya, 4 August 2015, http://en.aswatmasriya.com/news/details/17462