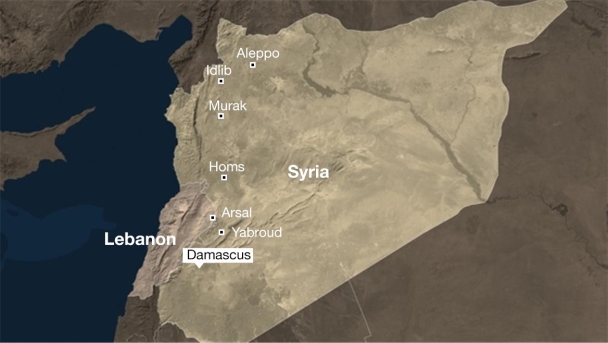

On 21 July 2017, Hezbollah launched the battle of Arsal(1) with around 3,000 fighters,(2) some of which were elite forces (as reported by Lebanese media)(3), including dozens of fighters from Tahrir al-Sham (“the Organisation for the Liberation of the Levant”, HTS).(4) The battle ended with an exchange treaty of dead bodies and prisoners (seven men and women from HTS and eight from Hezbollah [5]) and the evacuation of 120 HTS fighters and other refugees who wished to leave Arsal and go to Idlib under the sponsorship of the Lebanese General Security. The treaty was executed. The battle was preceded by negotiations with Saraya Ahl al-Sham (“the Company of the People of the Levant”), which did not participate in the battle but has about 200 fighters,(6) who were evacuated along with the other refugees to Eastern Qalamoun.

Thus, the entire area of Western Qalamoun is free of any armed forces that belong to the Syrian opposition except for Islamic State (IS) fighters, which amount to about 700 spread out in an area estimated by Lebanese security officials to be 200 square kilometres, extending from Syria’s Qara to Lebanon’s Qaa in Ras Baalbek.(7)

Background to the battle for Lebanon

The battle was preceded by an escalation of ‘nationalistic’ or xenophobic sentiments towards Syrian refugees in many Lebanese territories.(8) On the ground, the Lebanese army had raided Syrian refugee camps, in particular al-Nour and Qara camps, in Arsal on 14 July 2017. The army said it had encountered some militants, leading to the death of four Syrians, two of which were suicide bombers who killed themselves. The army arrested dozens of people, and the campaign ended with the death of four of the Syrian detainees. The Lebanese army’s investigations concluded that the deaths were of ‘natural causes’. However, many human rights associations have questioned Lebanon’s version of the story and claim that a fifth Syrian was also killed. The Lebanese authority has banned any independent investigation.(9)

During early preparations for the Arsal battle, the Lebanese army was intended to take the lead in the battle, especially after declaring its plan to carry out a military operation there amid calls from Hezbollah’s opponents to limit the operation to the Lebanese army without coordinating with the Syrian regime. However, as proven later, the battle was Hezbollah’s exclusively, and it only targeted HTS militants, and not IS. The battle began in Flitah in coordination with the Syrian side, whose air forces shelled the HTS militants’ locations even before the battle was officially declared. The attack was also in coordination with the Lebanese army, which protected the Lebanese side against the infiltration of any militants.

The battle of Arsal and the Syrian issue

The battle of Arsal lies at the heart of the Syrian issue. It took place in line with the main strategy of the Iranian-Syrian axis, as it aimed to:

1. Isolate the fighters from residential areas as much as possible, either through actual separation or via truces and agreements that constrain them and make them dependent on civilians or make civilians dependent on them, turning the fighters into an eventual trophy to be claimed when the conditions of battle allow for victory.

2. Impose demographic changes or sectarian cleansing and destroy the major cities, especially since the Arab Spring proved that true change could only come from major population blocs in cities; this stage began with collective displacement and killing, and the next stage – which has seemingly begun already – aims to restore the population under the condition of submission to authorities and reduce the number of Sunnis. This is exactly what happened in Homs and Aleppo, and even along the line extending from Damascus to Aleppo with Arsal and Flitah on the side. Hezbollah benefited from this procedure in the border areas, because the population blocs on the Syrian side have the same effect, especially in a sectarian conflict.

These two issues are apparent in the outcomes of the battle of Arsal, but in a Lebanese context. Regarding the first, Hezbollah chose the most pressing battle with Tahrir al-Sham because it is in close vicinity to the refugee camps, which interact with and support it. IS, on the other hand, is based in an isolated geographical area with little contact with the refugees in the adjacent camps. Furthermore, their authority extends to the Christian villages of Qaa and Ras Baalbek, so the party retreated and the Lebanese army moved in to deal with this challenge, especially since it still has members who have been detained by IS since 2014 and their fate remains unknown.(10)

Second is the issue of demographic change, which was also seen in the second displacement of the refugees after the agreement. HTS emphasised its goal of taking the refugees, particularly residents of the border areas with Lebanon, back to their land.(11) Regardless of how realistic this goal is, it was one of the main reasons they remained steadfast in Lebanon. With the defeat and evacuation of HTS, the inhabitants realised the unlikeliness and even impossibility of returning to their lands, which made them accept the second displacement from Arsal and its villages to Idlib.(12)

Several strategic steps that Hezbollah adopted in the Syrian war were seen in the battle of Arsal. Some even argue that Hezbollah learned some of these steps from its war with Israel and others from the Lebanese experience. These include:

1. Relying on proportionality in all the wars it wages; Hezbollah always chooses the battles it believes it can win, especially those that are beneficial politically and in terms of media coverage. Contrary to the party’s propaganda, the militants were few and isolated; the battle only needed to be well timed.

2. Establishing a new isolation zone on the Lebanese-Syrian border, which is almost complete, just like the one established by Israel in the south of Lebanon. Cleared of all inhabitants, these zones are said to facilitate the protection of Lebanese villages. They also separate the Syrian political Sunnis from the Lebanese ones, which is favoured internationally as no one wants Syrian turmoil to spread into Lebanon.

3. Expanding the authority of Hezbollah or the Lebanese security bodies over the entire Lebanese-Syrian border; this reassures the party and facilitates the continuance of ground communication with allies in Syria, Iraq and Iran.

4. Providing public morality to every battle it fights in Syria to avoid any response from Lebanon, relying on Lebanese diversity in the rejection of terrorism as well as the privileges of the Lebanese minorities in the region versus the Sunni Arab majority. Such a response is always possible in Lebanon in the face of the ‘alliance of minorities’, which was formed in parallel to Lebanon, the state of minorities. This process is easier under the current political status, under which the Lebanese have suffered from ‘terrorist attacks’ by Syrian groups or extremist groups from Syria. It is easier to emphasise this discourse at the local and international levels regardless of similar attacks by other parties, such as the two explosions at the al-Taqwa and Salam mosques in Tripoli in July 2013.(13)

The battle of Arsal and regional repositioning

Not only is the battle of Arsal in line with the major strategy of the Syrian-Iranian toward the Syrian question, it also provides confirmation that Hezbollah is working on the US and international priority of fighting terrorism because this priority achieves mutual goals in the region. This is the same approach adopted by Iran in Iraq, as the Popular Mobilisation Forces supported by Iran and the Iraqi government proceed under US and international air and fire cover with the help of US experts.

Such battles cannot be fought without international backing capable of halting the military escalation between Hezbollah and Israel because the war against ‘terrorism’ not only achieves numerous can achieve, it also ensures the prevention of escalation on the Israeli front. This explains why Israel was content about the peacefulness of the Lebanese border attributed to Hezbollah’s preoccupation with the battle of Arsal at the time despite the escalation that targeted Al-Aqsa mosque itself. This also explains the absence of serious regional and international opposition to Hezbollah’s military move – despites the possibility that it may boost Hezbollah’s military power and armament, which the international community naturally rejects.

The thing about Arsal, however, is that it took place within a trend of decreased, albeit temporary, involvement in the Syrian war in contrast with border battles, such as al-Qusayr battle, which aimed at greater interference in the Syrian war.(14) This may be attributed to recently escalated international developments, some of which aimed at Hezbollah’s regional and even domestic role.

Major developments include the relative decrease in the possibility of major battles in Syria after the Syrian-Iranian axis dominated Aleppo and the new international equation came about through a US-Russian understanding in the aftermath of the famous meeting between Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin in Hamburg in July 2017. The two countries agreed to create tension reduction zones and focus efforts on fighting terrorism in Syria and Iraq, represented in IS and al-Qaeda. Apparently, the most successful of these zones is the southern region near the border with Israel, which will help constrain the armed Syrians in the region (particularly Daraa and Quneitra) and protect Israel’s borders. It should also put an end to Hezbollah’s hopes of any possibility of being stationed there. This is of ideological and military importance, especially since it corresponds with the party’s self-definition as a resistance party with no sectarian motives.

This agreement is not expected to collapse, especially in this area, as it can last even if Russian-US relations deteriorate for any given reason. The agreement’s strength lies in its connection to Russia’s relations with Israel, Jordan and even some members of the ‘Arab axis’.

On the other hand, some aspects of US intervention in Syria have become more evident; Trump wants to prevent a land corridor from extending from Tehran to Beirut, even if it requires direct military intervention from Washington (like in al-Tanf)(15) regardless of whether it succeeds or fails. He also wants to undermine Iran’s role and the authority of its militias, including Hezbollah, in Syria in hopes that Russia will play a major role in this issue. Indeed, talks of a Russian role in the ‘withdrawal of foreign formations in Syria to minimise sectarian contradictions’ have recently received great attention. The Astana consultations, held on 14 and 15 March 2017, even discussed the matter of ‘observing the withdrawal of Shi'a formations that fight alongside al-Assad from several regions’. In addition, there was a proposal to ‘assign a specific region to be under Hezbollah’s control in Syria, followed by Hezbollah’s units’ gradual withdrawal from other regions, mainly the north of the country’.(16) Whether it sticks closely to this path, Russia probably wants to undermine Hezbollah’s political role,(17) which indicates the seriousness of US political orientation.

Furthermore, the United States is working to gradually impose financial and political sanctions on Hezbollah inside Lebanon. For instance, while Hezbollah was fighting what it described as ‘terrorism’ in the battle of Arsal, President Trump was in a joint press conference with Lebanese Prime Minister Saad Hariri who called Hezbollah ‘terrorists’.(18) The Secretary-General of the United Nations, Antonio Guterres, warned in his periodic report on the implementation of Resolution 1701 – pertaining to the Israeli war with Lebanon in 2006 – that ‘retaining Hezbollah and other armed groups undermines the authority of the state and contradicts with the responsibilities of the country’. This indicates a recommencement of international calls for limiting Hezbollah’s role inside Lebanon(19) with the aim of putting pressure on Hezbollah, because its disarmament has been complicated and delayed. These pressures also led pro-Hezbollah media and others to predict an upcoming Israeli war against Hezbollah. Many declarations, leaks and analyses reported a decrease of Hezbollah’s presence in Syria(20) to avoid any future war. In June 2017, Secretary General of Hezbollah Hassan Nasrallah announced the withdrawal of his militants from the eastern Lebanese mountain range and the area’s handover to the Lebanese army before the battle of Arsal.

Thus, the international policies currently being imposed are clearly an attempt to diminish Hezbollah’s role in Syria, which does not mean a break in the Syrian crisis but instead signifies the party’s need to protect its role in Lebanon and its stronghold in the Lebanese arena, at least until the picture is clear. Nasrallah even threatened in a speech on 23 June 2017 that if an Israeli war was launched against Lebanon, ‘no one knows if the war will be Lebanese-Israeli or Syrian-Israeli’. He also warned that ‘there will be room for tens of thousands or even hundreds of jihadists and fighters from all around the Arab and Islamic world to participate in that battle, from Iraq, Yemen, Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan and everywhere else’.(21)

Although this warning addressed Israel, it still anticipated and relates to the recent developments that may make Washington a key military player in the Syrian war.

Arsal in the Lebanese context

Through its circumstances and outcomes, the battle of Arsal revealed the depth of Hezbollah’s control within the structure of the Lebanese authority and its political, military and security institutions, especially since local and regional developments promoted its local presence – despite its involvement in the Syrian war – and did not help its local opponents.

The decreased importance of the Lebanese issue on the Saudi agenda and the decline of Saudi support for Saad Hariri in addition to his absence from Lebanon for three years and his withdrawal from Lebanese politics for five years (2011–2016)(22) weakened the Future Movement – Hezbollah’s main financial and political opponent. Hariri was forced return to the government in November 2016 under political conditions that include submitting to Hezbollah’s relative hegemony over the Lebanese state and acknowledging that ‘the armament and role of [the latter] is a regional issue that no Lebanese party can deal with’. Then came the Gulf crisis between Qatar and the blockading countries, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain and Egypt on 5 June 2017, besieging what was once called the ‘Sunni axis’ that supports the revolution. This further confused the Lebanese powers that opposed the Syrian-Iranian axis and lacked a regional strategy to face the developments of the Syrian crisis including the battle of Arsal.

The impact was clear in the consequences of the battle of Arsal even at the public level, as the battle received the consensus of the Shi'a majority supported by Speaker of Parliament Nabih Berri. It was also supported by the Free Patriotic Movement led by President Michel Aoun, and Hezbollah’s remaining Christian allies, and even by some of the silent Lebanese majority. On the other hand, neither the Future Movement, nor the Lebanese forces led by Samir Geagea and their allies showed any real objection to Hezbollah’s move. They rather just articulated a generic position that preferred that the Lebanese army would carry out the operation.

In other words, this regional confusion has been reflected in the supporters of March 14 alliance – who oppose Hezbollah – especially the Sunni public who is presumably the main host and supporter of Syrian refugees. These groups neither showed any real objection to the battle or its outcomes not sufficiently interfered, despite their social powers, to reassure the refugees or offer them any guarantees. This encouraged a number of registered refugees to move to Idlib (about 7,777 of the refugees are registered, but over 5,000 refugees left),(23) despite the difficult conditions and unknown future that awaits them there. Idlib is accused of being a centre for extremism, and yet refugees are displaced to it.

This battle showed unprecedented coordination between the Lebanese army and Hezbollah unlike, for example, the Sidon battle against Sheikh Ahmed al-Assir. Coordination in the Arsal battle was closer to that seen between the commands of two armies fighting on one battlefield. This military harmony may have resulted from recent changes in the Lebanese political scene, as the election of General Michel Aoun as president strengthened Hezbollah’s ties with the military and security forces. The Maronite army commander is historically and practically connected to presidency. This came along with the loss of three billion US dollars in Saudi aid to the Lebanese army(24) and the relative deterioration of the Lebanese army’s relations with western powers. Seemingly, this is what Trump is trying to rectify by reinforcing military cooperation, as his last meeting with Hariri indicated.(25)

Western security coordination in the fight against terrorism is strongly linked to the Lebanese presidency. Security challenges in the region have been an important factor in determining the president and filling the void, even if it is with an ally of Hezbollah like General Michel Aoun, as the US and western priority to fight terrorism comes even before fighting Hezbollah. Therefore, Washington did not criticise or object to the cooperation between the Lebanese army and Hezbollah.

As such, the situation has repromoted the ‘golden triangle’ (i.e. ‘army, people and resistance’), which Hezbollah was keen to consolidate politically and in government to justify its ‘armament’, and whose presence began to fade in 2008 after Hezbollah’s militants seized control of Beirut and used weapons inside of Lebanon, leading to the triangle’s rejection by the March 14 alliance, its followers and parts of the Lebanese silent majority. However, after Arsal, it returned so strongly that Speaker of Parliament Nabih Berri called it ‘the diamond triangle’. This reflects developments in relations between the army and Hezbollah, which have now become a reality with Hezbollah’s alliance with the president and do not need to be documented in a government statement. This also confirms the Christians’ acceptance of the equation and of Hezbollah’s role in protecting the borders with Syria and Israel, especially with the location of Christian regions (in Qaa and Ras Baalbek) near the refugee camps and the Syrian militants of IS.

This ‘triangle’ once allowed Hezbollah to receive legal recognition from the Lebanese government and military. Since its revival after the battle of Arsal, Hezbollah will certainly work to expand its armed presence in the region, even if it hands the sites over to the Lebanese army. It will also maintain armed bases in the adjacent Shi'a villages because its role in protecting the border with Syria is now stronger.

Conclusion

Hezbollah has paid a high price despite the magnitude of the battle: 29 people were killed(26) and a prisoner exchange was conducted. The latter revealed the Lebanese government’s submission to Hezbollah’s demands to release ‘presumed terrorists’, some of whom had been sentenced and one of whom is Lebanese, from Lebanese jails for the exchange. The government itself was part of the negotiations and their outcomes, indicating that Hezbollah’s influence in the structures of Lebanese authority has increased. This will surely force regional and international powers to reconsider its strength and the way they deal with it, especially since its role in in the fight against terrorism has been established, even if it has not been given international legitimacy.

Nevertheless, the Lebanese forces that oppose Hezbollah’s armament are not expected to start a heated confrontation with it, like they did after Rafic Hariri was murdered in 2005, unless the regional and international position changes first. Lebanon is not a regional or international priority, and fighting terrorism still comes before facing Iran. These powers prefer to wait and see what happens to the Syrian crisis now that it has become a centre for international activity (as per Trump’s strategy), which is still unclear, and to the Gulf crisis, which has the most serious implications for the Lebanese issue.

One can say that all Lebanese sects are wagering on the ability of the Sunnis, especially the Future Movement, to persist and for their leadership to be given a chance. The Sunni political position prevents them from taking part in the ongoing sectarian war and prompts them to overlook Hezbollah’s armed presence on the borders in Syria or even within Lebanon, especially since the latter is one of the few remaining places – if not the only one – that coexists with Iran’s dominance without turning to armed confrontation like in Syria, Iraq and Yemen.

One can also say that all Lebanese communities coexist , albeit in their own ways, with Iranian dominance, just like they did in the past with Syrian dominance. However, Tehran still needs Hezbollah’s regional role, as Hezbollah has yet to reach the extent of its intervention in Syria or the beginning of its decline within Lebanese authority. On the other hand, the Syrian war has almost run out of justifications; the game is now is too big for Hezbollah due to international intervention. Therefore, the party must return to Lebanon and fortify itself there.

(1) (2017) “Hezbollah attacks Arsal without Lebanese Army”, Al Jazeera Net, 21 July, http://www.aljazeera.net/news/arabic/2017/7/21/%D8%AD%D8%B2%D8%A8-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%84%D9%87-%D9%8A%D9%87%D8%A7%D8%AC%D9%85-%D8%B9%D8%B1%D8%B3%D8%A7%D9%84-%D8%AF%D9%88%D9%86-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AC%D9%8A%D8%B4-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%84%D8%A8%D9%86%D8%A7%D9%86%D9%8A (accessed 21 July 2017).

(2) Wesam Ismail (2017), “3000 Hezbollah militants in Arsal Battle: Resolution not before another week?’”, An-Nahar, 21 July, https://www.annahar.com/article/624017-3000-مقاتل-من-حزب-الله-في-معركة-عرسال-الحسم-لن-يكون-قبل-أسبوع (accessed 21 July 2017).

(3) Mohammed Alloush (2017), “Hezbollah mobilises two elite troops for Al-Jaroud Battle: This is the attack strategy”, Elnashra, 18 July, http://www.elnashra.com/news/show/1119877/%D8%AD%D8%B2%D8%A8-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%84%D9%87-%D8%AD%D8%B4%D8%AF-%D9%81%D8%B1%D9%82%D8%AA%D9%8A%D9%86-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%86%D8%AE%D8%A8%D8%A9-%D9%84%D9%85%D8%B9%D8%B1%D9%83%D8%A9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AC%D8%B1%D9%88%D8%AF:-%D9%87%D8%B0%D9%87-%D8%A7%D8%B3%D8%AA%D8%B1 (accessed 27 July 2017).

(4) Wafiq Qanso (2017), “Army preparing, IS planning suicide bombings: 5000 displaced people preparing to leave with Al-Nusra militants”, Al-Akhbar, 29 July, http://www.al-akhbar.com/node/280990 (accessed 6 August 2017).

(5) Phone conversation with Mazen Ibrahim, Chief of Al Jazeera Bureau in Beirut, 3 July 2017.

(6) Ibid.

(7) Ibid.

(8) Discrimination continues in Lebanon against the refugees, but the escalation preceding the battle of Arsal seemed to be an organised campaign, which may have resulted from media incitement, paving the way for the battle and its outcomes.

(9) (2017) “The Deaths of 10 Syrian refugees detained by the Lebanese Army”, Al Jazeera Net, 5 July, http://www.aljazeera.net/news/humanrights/2017/7/5/%D9%88%D9%81%D8%A7%D8%A9-%D8%B3%D9%88%D8%B1%D9%8A%D9%8A%D9%86-%D9%85%D9%88%D9%82%D9%88%D9%81%D9%8A%D9%86-%D8%A8%D9%84%D8%A8%D9%86%D8%A7%D9%86-%D9%88%D8%A7%D8%AA%D9%87%D8%A7%D9%85-%D8%A8%D8%AA%D8%B9%D8%B0%D9%8A%D8%A8%D9%87%D9%85 (accessed 27 July 2017); see also, (2017) “The Deaths and Alleged Torture of Syrians in the Lebanese Army’s Custody”, Human Rights Watch, 20 July, https://www.hrw.org/ar/news/2017/07/20/306896 (accessed 27 July 2017).

(10) The Islamic State has detained nine members of the Lebanese army and is believed to have captured the bodies of Abbas Medlej and Yahya Khadr. The Lebanese militants were detained August 2014.

(11) (2017) “The Emir of Tahrir al-Sham in Qalamoun addresses Hezbollah”, Orient Net, 20 June, http://orient-news.net/ar/news_show/136633/0/%D8%A3%D9%85%D9%8A%D8%B1-%D9%87%D9%8A%D8%A6%D8%A9-%D8%AA%D8%AD%D8%B1%D9%8A%D8%B1-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B4%D8%A7%D9%85-%D8%A8%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%82%D9%84%D9%85%D9%88%D9%86-%D9%8A%D9%88%D8%AC%D9%87-%D8%B1%D8%B3%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A9-%D9%84-%D8%AD%D8%B2%D8%A8-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%84%D9%87 (accessed 6 August 2017).

(12) Especially since the residents of regions under Hezbollah’s control were among the first displaced, like the inhabitants of al-Qusayr whose town was a headquarters for Hezbollah on the Damascus-Homs line. They believe that Iran will insist on permanently displacing them or rendering them an absolute minority, so they turned to the armed option. They seem to have lost hope after this battle.

(13) (2016) “The transcript of the accusative decision in the bombings of Al-Taqwa and Al-Salam mosques in Tripoli”, An-Nahar, 2 September, https://www.annahar.com/article/460527-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%86%D8%B5-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AD%D8%B1%D9%81%D9%8A-%D9%84%D9%84%D9%82%D8%B1%D8%A7%D8%B1-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A7%D8%AA%D9%87%D8%A7%D9%85%D9%8A-%D9%81%D9%8A-%D8%AA%D9%81%D8%AC%D9%8A%D8%B1-%D9%85%D8%B3%D8%AC%D8%AF%D9%8A-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AA%D9%82%D9%88%D9%89-%D9%88%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B3%D9%84%D8%A7%D9%85-%D9%81%D9%8A-%D8%B7%D8%B1%D8%A7%D8%A8%D9%84%D8%B3 (accessed 27 July 2017).

(14) Chafic Choucair (2013), “The Syrian Battle of al-Qusayr: Consequences of Hezbollah’s Lebanese and regional interventions”, Al Jazeera Centre for Studies, 8 May, http://studies.aljazeera.net/ar/reports/2013/05/20135711716642298.html (accessed 27 July 2017).

(15) (2017) “Washington confirms raid: Al-Tanf is a red line for the regime and Iran”, Almodon Online, 19 May, http://www.almodon.com/arabworld/2017/5/19/%D8%BA%D8%A7%D8%B1%D8%A9-%D8%AC%D9%88%D9%8A%D8%A9-%D8%A3%D9%85%D9%8A%D8%B1%D9%83%D9%8A%D8%A9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AA%D9%86%D9%81-%D8%AE%D8%B7-%D8%A3%D8%AD%D9%85%D8%B1-%D8%B9%D9%84%D9%89-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%86%D8%B8%D8%A7%D9%85-%D9%88%D8%A5%D9%8A%D8%B1%D8%A7%D9%86 (accessed 27 July 2017); See also, Nabil Owda, (2017), “The Jordanian role in Syria: Safe zones and the future of the crisis”, Al Jazeera Centre for Studies, 15 June, http://studies.aljazeera.net/ar/reports/2017/06/170615101809190.html (accessed 27 July 2017).

(16) (2017) “Russian militants put Hezbollah under surveillance”, Russia Today, 19 March, https://arabic.rt.com/press/868793-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B9%D8%B3%D9%83%D8%B1%D9%8A%D9%88%D9%86-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B1%D9%88%D8%B3-%D9%8A%D8%B6%D8%B9%D9%88%D9%86-%D8%AD%D8%B2%D8%A8-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%84%D9%87-%D8%AA%D8%AD%D8%AA-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%85%D8%B1%D8%A7%D9%82%D8%A8%D8%A9/ (accessed 27 July 2017).

(17) Sami Khalifa (2017), “Russia wants Hezbollah out of Syria”, Almodon Online, 19 July 2017, http://www.almodon.com/politics/2017/7/19/%D8%B1%D9%88%D8%B3%D9%8A%D8%A7-%D8%AA%D8%B1%D9%8A%D8%AF-%D8%AD%D8%B2%D8%A8-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%84%D9%87-%D8%AE%D8%A7%D8%B1%D8%AC-%D8%B3%D9%88%D8%B1%D9%8A%D8%A7 (accessed 27 July 2017).

(18) (2017) “Trump: Al-Assad will not get away with his crimes, and Hezbollah is terrorist…Hariri: We are committed to international resolutions", An-Nahar, 25 July, https://www.annahar.com/article/626514-%D8%AA%D8%B1%D8%A7%D9%85%D8%A8-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A7%D8%B3%D8%AF-%D9%84%D9%86-%D9%8A%D9%81%D9%84%D8%AA-%D9%85%D9%86-%D8%AC%D8%B1%D8%A7%D8%A6%D9%85%D9%87-%D9%88%D8%AD%D8%B2%D8%A8-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%84%D9%87-%D8%A7%D8%B1%D9%87%D8%A7%D8%A8%D9%8A-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AD%D8%B1%D9%8A%D8%B1%D9%8A-%D9%85%D9%84%D8%AA%D8%B2%D9%85%D9%88%D9%86-%D8%A8%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%82%D8%B1%D8%A7%D8%B1%D8%A7%D8%AA-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AF%D9%88%D9%84%D9%8A%D8%A9 (accessed 27 July 2017).

(19) (2017) “The United Nations and Aoun: Disarmament Strategy”, An-Nahar, 10 March, https://newspaper.annahar.com/article/551627-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A3%D9%85%D9%85-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%85%D8%AA%D8%AD%D8%AF%D8%A9-%D9%88%D8%B9%D9%88%D9%86-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A7%D8%B3%D8%AA%D8%B1%D8%A7%D8%AA%D9%8A%D8%AC%D9%8A%D8%A9-%D9%84%D9%86%D8%B2%D8%B9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B3%D9%84%D8%A7%D8%AD (accessed 27 July 2017).

(20) Walid Choucair (2017), “Hezbollah repositions in Syria because Trump categorised it as ‘terrorist’?”, Al-Hayat, 14 May, http://www.alhayat.com/Articles/21847120/-%D8%AD%D8%B2%D8%A8-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%84%D9%87--%D9%8A%D8%B9%D9%8A%D8%AF-%D8%AA%D9%85%D9%88%D8%B6%D8%B9%D9%87-%D9%81%D9%8A-%D8%B3%D9%88%D8%B1%D9%8A%D8%A9-%D9%84%D8%A3%D9%86-%D8%AA%D8%B1%D8%A7%D9%85%D8%A8-%D9%88%D8%B6%D8%B9%D9%87-%D9%81%D9%8A-%D8%B3%D9%84%D8%A9-%D9%88%D8%A7%D8%AD%D8%AF%D8%A9-%D9%85%D8%B9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A5%D8%B1%D9%87%D8%A7%D8%A8%D8%9F (accessed 27 July 2017).

(21) (2017) “Nasrallah: War with Israel may bring in fighters from Iran, Iraq and others”, Reuters, 23 June, http://ara.reuters.com/article/topNews/idARAKBN19E1WQ (accessed 27 July 2017).

(22) (2014) “Saad Hariri in Beirut after three years”, Asharq al-Awsat, 9 August, https://aawsat.com/home/article/155391 (accessed 27 July 2017).

(23) Phone conversation with Mazen Ibrahim, Chief of Al Jazeera Bureau in Beirut, 3 July 2017.

(24) (2016) “Saudi Arabia halts aid to Lebanese Army”, Al Jazeera Net, 19 February, http://www.aljazeera.net/news/arabic/2016/2/19/%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B3%D8%B9%D9%88%D8%AF%D9%8A%D8%A9-%D8%AA%D9%88%D9%82%D9%81-%D9%85%D8%B3%D8%A7%D8%B9%D8%AF%D8%A7%D8%AA%D9%87%D8%A7-%D9%84%D9%84%D8%AC%D9%8A%D8%B4-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%84%D8%A8%D9%86%D8%A7%D9%86%D9%8A (accessed 27 July 2017).

(25) (2017) “Trump: US aid ensures Lebanese army is the only power in Lebanon”, BBC Arabic, 26 July, http://www.bbc.com/arabic/media-40727296 (accessed 27 July 2017).

(26) Phone conversation with Mazen Ibrahim, Chief of Al Jazeera Bureau in Beirut, 3 July 2017.