Introduction

North Africa and the Middle East are struggling with their present; let alone how to shape their future. The promise of the 2011 uprisings has turned into growing malaise and widespread deception by the poor performance of Islamist, secular, military, nationalist, and other brands of Arab governments. After seven years of high expectations, the Arab story of reform and democratization has become a daunting cliffhanger. The main question now is how we got here. Why there is so much concentration of conflict and violence in this strategic region located at the heart of the world with enormous natural and human resources. Why is there still dire shortage of democratic steps and civility in the Arab public discourse across the region? One good example in Saudi Arabia, Tweeter has served as the best weapon of mass stigmatization of Qatari officials and their allies. Another intriguing question; what prevents Arab societies from forging a smooth path to modernity, welfare, and democracy? Are there any real prospects of an Arab age of enlightenment to help address this difficult Arab pregnancy of democracy?

The following paper is part one of a lecture delivered by Mohammed Cherkaoui at Friedrich-Alexander-University Erlangen-Nürnberg in Germany October 25th. The second part will be posted soon.

The ongoing civil wars, civilian devastation, and the political struggle of states and non-state actors alike across the region do not have one set of deep-rooted causes, but a diversity of economic, geo-strategic, cultural, ethno-nationalist, historical, and sometimes tribal factors. Therefore, academic tools of analysis require a multi-disciplinary approach and crossing over to other fields of knowledge. Moreover in the field of conflict resolution, peacebuilding, and cultural studies, He argued for a “cross-disciplinary pursuit of deconstructing the drivers of extremism, Jihadism, and other forms of political violence amidst the debate over the significance of the multi-disciplinarily approach versus the inter-disciplinary approach.” He organized his paper around three themes: a) religiosity as new geopolitics within the advocacy of the political Islam movements across the region; b) new Arab realpolitik in terms of the reemergence of Arab deep states stronger after the turmoil of 2011; and c) regressed Arab sub-identities while national identities have taken the back seat behind the power of sectarianism. I will also propose a few reflective conclusions on the new age of Arab sectarianism and the struggle for modernity and democratization.

One of the challenges now is how address the divergence between the religiosity of peace, as a central pillar of the Islamic discourse, and the civility of religion in shaping the political system in the region. The question remains: how to organize the interconnectedness between the mosque, the church, the temple, the ministry, the parliament and the public opinion, and promote openness, diversity, and global values. Most of the political actors in the region have had a religious platform -Islamic or Islamist - and a favorable discourse of religiosity.

My hope is to help streamline the tools and concepts of various social sciences, including social psychology, political sociology, anthropology, cultural studies, economics, and international relations, to help provide a well-nuanced science of conflict, or what peace theorist Johan Galtung likes to call ‘conflictology’, in the study of both structure and agency. Why individuals kill in the name of defending the virtues of their holy books, and, as followers of Islam, Christianity, and Judaism, still insist they are activists for peace. I have not mentioned the big elephant in the room, terrorism and counterterrorism, since the United Nations, the European Union, the Pentagon, and other governments and international institutions, have not reconciled their differences on what ‘terrorism’ is out of the 109 circulating definitions; and how it should be addressed as one specific category of political violence.

|

| [Al Jazeera] |

A Brief Diagnosis

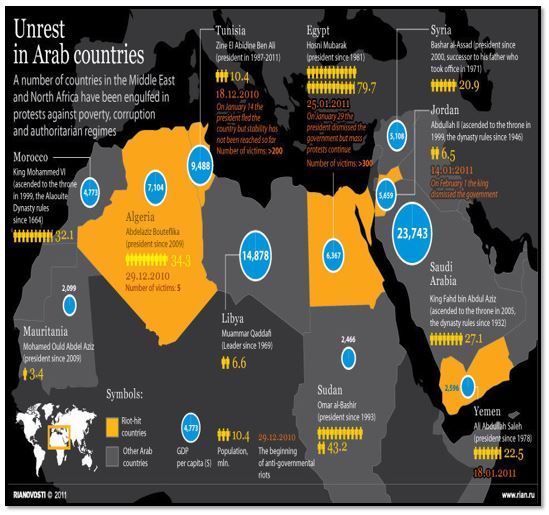

To say the Middle East is in crisis at these turbulent times is an understatement. Three nations Syria, Yemen, and Libya are now synonymous to vicious civil wars, shrewd politics of super and regional powers and armed militias, increasing deaths among civilians, and struggle of the United Nations peacemaking missions in Syria, Yemen, and Libya. Now, the calculation of the Russian, Iranian, Turkish, Israeli, American strategic interests in the province of Idlib in particular, and in Syria in general, may lead to a regional war if these players fail to hold a stable balance of power in the future. The classical hatred between Israel and Iran and their race for nuclear armament remain more alarming than ever. Last May, Donald Trump decided to withdraw from the seven-nation-signed Nuclear Deal and to impose sanctions on all businesses and governments that have invested inside Iran. During the United Nations General Assembly last month, he expected “all nations to isolate Iran’s regime”. (1) These developments have given Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu more hope to neutralize Iran, and rejoice a would-be Israeli military supremacy in the region.

Other nations like Iraq and Lebanon are captive of sectarian politics and stubborn rivalries that seek to dominate the parliament and other government agencies. To the south, the six nations of the Gulf Cooperation Council have exhausted their sense of alliance, and turned against each other. The personal animosity between Mohamed bin Zayed of the Emirates, Mohamed bin Salman of Saudi Arabia, and Tamim of Qatar has taken the new crisis to uncharted territories. Sixteen months into the blockade of Qatar, the Kuwaiti mediation is still struggling to hammer down the Emirati-Saudi-Qatari differences, and President Trump has failed to host a US-Gulf summit amidst his pursuit of mobilizing the six Gulf nations, Egypt, and Jordan into the formulation of an Arab NATO Alliance. One most recent crisis is the Saudi monarchy controversy and the immorality of a crown prince who is allegedly involved in ordering the killing of Saudi journalist and intellect who opted for self-exile in the United States in 2017. This kind of assassination has undermined the most conservative political systems in the region, and has effectively destabilized the notion of an Arab model of governance. It has also raised new challenges for the political theory as well as the field of international relations.

Egypt is an interesting case of the militarization of politics and society. The recent court sentences of death penalty for 75 activists and members of the Muslim Brotherhood is another indicator of shortsighted politics of President Sisi, who believes in the eradication of his opponents Islamists, secularists, modernists, and otherwise. The Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, the powerful military institution in Cairo, continues to benefit from the monopoly of 40% of the national economy. Sudan and South Sudan are still in a deadlock of more than one conflict: there has escalation of three disputes over Abyei border and the states of South Kordofan and Blue Nile. Earlier this month, the Sudanese government requested the Security Council to speed up its approval of doubling the regional protection force, from 4000 to 8000 soldiers with Sudan, Uganda, Djibouti and Somalia contributing troops, with the hope rival leaders in South Sudan would "give peace a chance.” (2)

In North Africa, the situation is not rosy either. Libya is a complex case of struggling political transition, renewed violence, uncontrolled migration, and the reemergence of slavery. A number of African refugees were sold for the equivalent of $800 to do farm work in certain tribal-controlled areas. In the last six years, the United Nations has deployed four envoys for the Libyan conflict after the fall of Muammar Qaddafi. Accordingly, the United Nations Support Mission in Libya (UNSMIL) has hosted scores of meetings with various Libyan leaders in Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco. However, the political deadlock and sporadic violence remain the talk of the day either in the two centers of power: Tripoli in the west and Tobruk in the east, with different affiliations of support with certain regional and international actors, namely France, Turkey, Egypt, United Arab Emirates, and Qatar.

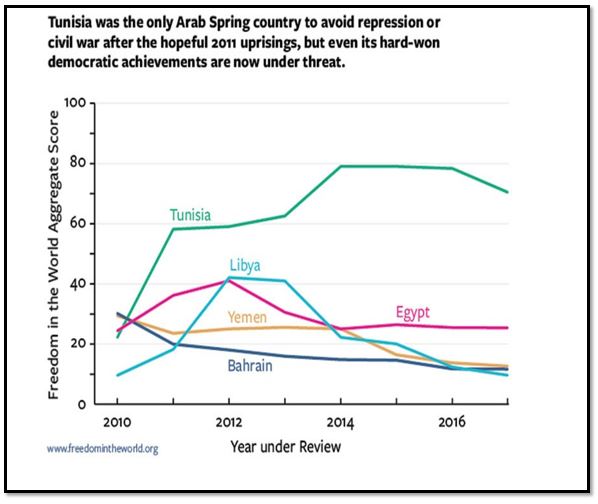

In neighboring Tunisia, which is considered the only hope of the Arab uprisings, or the so-called ‘Arab Spring’, domestic politics has been captive, in the last few months, by a show of force between Hafedh Caid Essebsi, son of the president and leader of the ruling party, Nida Tounes, and prime minster Youssef Chahed. The Prime Minister, who has been in office for more than two years, “has led an aggressive reform programme, backed by the IMF, to control Tunisia’s deficit. But, his privatization plans have been rejected by the powerful General Labor Union (Union Générale des Travailleurs Tunisiens, UGTT), which has backed Essebsi’s calls for his resignation.” (3) Moreover, there is an emerging rift within the post-2014 election alliance between the ruling party Nida Tounes and the Islamist party Ennahda. Ennahda has rejected calls “to replace Chahed out of fear of a collapse in the economy, not least because Chahed is Tunisia’s ninth prime minister in only seven years.” (4) However, President Baji Caid Essebsi asserted in a recent TV interview, "The consensus and relationship between me and Ennahda has ended, after they chose to form another relationship with Youssef Chahed." (5)

|

| Recent protests in Tunisia: The slogan reads “2018: The shopping bag is empty” [Getty] |

Algeria in another interesting case of economic despair, societal malaise, and the extension of the mandate of an invisible and ailing president. There has been heated political debate among many Algerians about one dilemma: who really runs Algeria? The de-facto decision-making is presumed to reside among a small circle of shadowy politicians, military leaders, and intelligence officials, collectively known as le pouvoir (French for “the powers that be”), amidst an open-ended battle for influence within the political and military establishment. During Chancellor Merkel’s recent visit to Algiers, President Bouteflika, who has been in a wheel chair since his crippling stroke in 2013, could not mumble more than a few words. Still, the official narrative echoing in the corridors of the presidential palace in Zeralda, west of Algiers, is that Bouteflika “is well”! His entourage is pushing for his presidential bid for the fifth time in the upcoming elections scheduled for April 2019. Algeria represents an ironic contrast: it is North Africa’s oil superpower, and the unemployment, particularly among the youth, rate exceeds 20 percent, while the country ranks among the world’s 10 most corrupt. (6) As one Algeria observer points out, “In light of the dire situation facing the country from the economic, political, and security sectors, nominating Bouteflika for an illegal fifth term would likely serve as a catalyst to much larger instabilities than the regime is currently combating.” (7)

To the west, the riots in Rif in northern Morocco after the killing of fishmonger Mohsen Fikri in the port-city of Al Hoceima October 28, 2016, mining workers’ protest in Jerada, and the open-ended boycott of certain brands of gas, water, and milk, have revealed the struggle of the police-intelligence apparatus in containing a bad situation of popular resentment movement. The protests have showcased deepening fragmentation between state and society, and led to significant loss of the Monarchy’s credibility and social capital. Makhzen, the local term for deep state, has positioned itself as the guardian of the monarchy in Morocco; and seems to have exhausted its tools of power politics. Makhzen’s tactics derive from the classical text of realpolitik and the top-down structural paradigm. They do not show real adjustment, or realignment, to the twenty-first reality and nuances of the emerging bottom-up collective action, power of social movements, or people politics. The draconian verdicts of twenty-year sentences against Nacer Zefzafi and forty-nine other Rif activists in July have triggered an outcry of denunciation from Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch and world defenders of individual liberties and freedom of speech.

On the Western coast of the Atlantic, Mauritania’s recent parliamentary elections results have empowered the ruling party, the Republican Party for Democracy and Renewal, and President Mohamed Ould Abdel Aziz to declare a direct crackdown on Islamic educational institutions. Earlier this month, student demonstrations erupted in the capital Nouakchott in protest against the closure of the University of Abdullah ibn Yasin (UAIY) and the Centre for Training Islamic Scholars (CTIS). President Abdel Aziz cautioned against political Islam, and stated it “was dangerous, as its ideology had “destroyed whole nations.” (8)

In retrospect, North Africa and the Middle East are struggling with their present; let alone how to shape their future. The promise of the 2011 uprisings has turned into growing malaise and widespread deception by the poor performance of Islamist, secular, military, nationalist, and other brands of Arab governments. After seven years of high expectations, the Arab story of reform and democratization has become a daunting cliffhanger. The main question now is how we got here. Why there is so much concentration of conflict and violence in this strategic region located at the heart of the world with enormous natural and human resources. Why is there still dire shortage of democratic steps and civility in the Arab public discourse across the region? One good example in Saudi Arabia, Tweeter has served as the best weapon of mass stigmatization of Qatari officials and their allies. Another intriguing question; what prevents Arab societies from forging a smooth path to modernity, welfare, and democracy? Are there any real prospects of an Arab age of enlightenment to help address this difficult Arab pregnancy of democracy?

|

| [Freedom in the World Organization] |

How Did We Get Here?

First, I would like to argue against the assumption of one factor of this Arab decline, or the singularity of a driving force, behind what qualifies as semi-anarchy of the Arab system in 2018. There is no much choice in either categorizing Syria, Iraq, Yemen, Lebanon, South Sudan, and Libya as fragile states or failed states. Most of these Arab nations rank among the top fifteen on the 2018 Fragile States Index. (9) Other states in the region cannot claim much stability even the monarchies in Morocco and Jordan, which thought they could jump over the turbulences and protests that were loud in public squares in spring 2011.

I perceive Arab societies now as being stuck inside a dark and suffocating triangle. There is tightening force within the three sides from which I have constructed my suggested scope of analysis: “The 3-R dilemma: religiosity of peace, realism of war, and regressed sub-identities in the Middle East”. My presentation this evening focuses on the structural and socio-cultural dynamics. My aim is to address what has pushed the Middle East and North Africa into this challenging pitfall by deconstructing the three sides of the metaphorical triangle. I have organized my paper around three themes: a) religiosity as new geopolitics within the advocacy of the political Islam movements across the region; b) new Arab realpolitik in terms of the reemergence of Arab deep states stronger after the turmoil of 2011; and c) regressed Arab sub-identities while national identities have taken the back seat behind the power of sectarianism. I will also propose a few reflective conclusions on the new age of Arab sectarianism and the struggle for modernity and democratization.

Secondsince the beginning of the new century, Arab societies have witnessed a collision between two forces: status quo versus calls for change. The first camp, which includes politicians, financers, top ranking military officers and other profiteers, has pushed hard to maintain the status quo to help prolong their interest and political survival. Moreover, deep state agents have reemerged stronger with a staunch will to protect their affiliated centers of power and are less enthusiastic to consider the ethics of legitimacy or moral politics. In contrast, the disgruntled educated youth majority and resentful middle-aged Arabs have sustained the call for change, and pushed the envelope for comprehensive and tangible change. What happened in early 2011 can be perceived as a rare moment of an Arab pure reason, as I adopt Emmanuel Kant’s terminology. Overall, each camp is well equipped with various justifying narratives; and tends to manipulate the socio-cultural reservoir of the respective society.

On the extreme spectrum of politics, militant groups are getting more sophisticated and more determined to destabilize the Arab states’ grip on power and resist the intervention of foreign powers. For example, Hutis in Yemen, Hezbollah in Lebanon and Syria, Hashd Ashaabi in Iraq, and scores of armed groups in Libya and southern Algeria have often outperformed the local governments by pushing their action capabilities into a merely reactive mode of salvaging bad situations and enduring the political calamities of political violence. Now, the impact of non-state actors is on the rise and decides most of the political agenda across the region, whereas most Arab states remain on the receiving end. This situation reminds me of the old saying of Thucydides, historian of the Peloponnesian War some 2400 years ago, when he wrote, “the strong do what they can, and the weak suffer what they must.”

|

| [Novosti] |

Third, one of the challenges now is how address the divergence between the religiosity of peace, as a central pillar of the Islamic discourse, and the civility of religion in shaping the political system in the region. The question remains: how to organize the interconnectedness between the mosque, the church, the temple, the ministry, the parliament and the public opinion, and promote openness, diversity, and global values. Most of the political actors in the region have had a religious platform -Islamic or Islamist - and a favorable discourse of religiosity. With the exception of Turkey, all the countries of the Middle East have opted for a religion-centric Muslim-Arab identity. With the claimed religious tolerance and multiculturalism in the Middle East, these majority identities have become expansionist among Arab communities abroad. Ironically, some leaders of the extreme left communist parties, as is the case of the Party of Progress and Socialism in Morocco, have come closer to the religious discourse to help compete with the mainstream Islamist movement parties that were top winners in the 2012 elections in several Arab countries. Let me address the religiosity of peace, or what I call alarming religiosity.

Alarming Religiosity

To be a religious person, either a Muslim, Christian, or Jew, is a positive drive for spirituality and societal tolerance. However, religiosity tends to have wider connotations and unlimited reverberations. It includes experiential, ritualistic, ideological, intellectual, consequential, creedal, communal, doctrinal, moral, and cultural dimensions, as Barbara Holdcroft argues in her essay published in the Journal of Inquiry and Practice.(10) Religiosity can be a loaded term with several synonyms such as ‘religiousness’, ‘orthodoxy’, ‘faith’, ‘belief’, ‘piousness’, ‘devotion’, and ‘holiness’. As you notice, these alternative terms derive mostly from an English dictionary and a Christian context. I must admit it has not been an easy task, for me at least, to decide the best translation of ‘religiosity’ into Arabic; and whether the word ‘tadayoun’تديّن (devoutness) would fit in this context. Other alternatives would go as far as ‘zouhd’ الزهد (asceticism), ‘taqwa’ تقوى (piousness), or ‘tasawwof’ تصوّف (Sufism). This could be a lost-in-translation dilemma.

Religiosity remains a complex construct across all religions and a challenging research subject for social sciences, not because of its theological value alone, but rather for its ideological and cultural load as manipulated now by most militant non-state actors. Scholars like Gerhard Lenski identified four different ways in which religiosity might be expressed: associational, communal, doctrinal, and devotional. (11) In their book “Religion and Society in Tension”, Charles Glock and Rodney Stark defined five dimensions of religiosity: experiential, ritualistic, ideological, intellectual, and consequential.

Current waves of extremism are not to be blamed on Koran or any other holy textbook. Instead, we need to probe into the mental and psychological residue of any Islamic, Christian, or Jewish religiosity under the effect of culture of extremism and the claim of peacemaking. This brings us to the dilemma of religious congruence, since I assume that religious beliefs and values are neatly integrated in our minds and souls. There has been continuous fragmentation within each local culture while animosity has deepened among various cultures in the region. As Duke University professor Mark Chaves poked into what he called ‘the religious congruence fallacy’, he proposes a good example of religious congruence. He wrote, "Observant Jews may not believe what they say in their Sabbath prayers. Christian ministers may not believe in God. And people who regularly dance for rain don’t do it in the dry season.” (12)

The Institute for Economics and Peace, which pursues proper ways to quantify peace and its benefits, has tackled the question: is religion the main cause of conflict today? After studying the state of thirty-five armed conflicts in 2013, the Institute concluded that religious elements did not play a role in fourteen, or 40 percent, of these conflicts. It also found that “religion was only one of three or more reasons for 67 per cent of the conflicts where religion featured as a factor to the conflict.” (13) However, Douglas Johnston, president of the International Center on Religion and Diplomacy, has identified conditions in several conflict situations that lend themselves to faith-based intervention:

First, religion is a significant factor in the identity of one or both parts to the conflict;

Second, religious leaders on both sides of the dispute can be mobilized to facilitate peace;

Third, protracted struggles between two major religious traditions transcend national borders, as has been the case over time with Islam and Christianity; and/or

Fourth, forces of realpolitik have led to an extended paralysis of action. (14)

Within this concept of faith-based conflict transformation, Berlin hosted the conference on the Responsibility of Religions for Peace Last year. Dirk Lölke, head of the task force at the Directorate-General for Culture and Communication at the Federal Foreign Office stated that “if foreign policy fails to leverage the potential (of listening to different views on conflict from representatives of religious communities), we will miss out on an important part of discourse in other countries.” (15)

What is of interest in the case of North Africa and the Middle East is two specific dimensions. The first is the ideological dimension that is “constituted by expectations that the religious will hold to certain beliefs” (i.e., professed doctrines). The second is the intellectual dimension which has to do, as Glock and Stark would argue, with the expectation that the religious person will be informed and knowledgeable about the basic tenets of his faith and sacred scriptures” (i.e., history, sacraments, morality…)” (16)

I like to go back to the fourth point Douglas Johnson makes about how “forces of realpolitik have led to an extended paralysis of action.” Among these forces of realpolitik are the religiously defined non-state actors, such as the Hutis in Yemen, Hezbollah in Lebanon and its military support for Al Assad regime in Syria, Al-Hashd Ashaabi in Iraq, and Ansar Al sharia in Libya, which imply some ‘divine’ reason and ‘mystic’ will in waging war against the so-called ‘infidels’ internally and externally. They tend to sugarcoat their discourse of using lethal force against their enemies with some overstretched interpretations of selected religious texts, either from Koran and Hadith. Most Islamist parties have relied on the religiosity, not only at the individual level, but also at the collective and societal level. The shift from western-designed clothes to hijab حجابand abayaعباية among the majority of Arab women, the rise of faith-based TV shows, and the rise of worshippers in Mosques in recent years are goof indicators of this trend of not only spiritual religiosity, but also political religiosity. Along this transformation of Arab societies, religiosity has become the new geopolitics of the Islamist movement.

|

| [Freedom House] |

Religiosity as New Geopolitics

One should consider the temporality of the Arab uprisings vis-à-vis the revival of the fifty shades of Salafisms and Islamisms across the region. I am using both terms, Salafisms and Islamisms, in plural. One good example is the leaders of the ruling party in Morocco, Justice and Development, reject the notion they are an extension to the Justice and Development party in Turkey or an affiliation of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt. As Islamist movement scholar Geneive Abdo points out, “Today’s charismatic religious ideologues first began to make their presence felt during the 1970s, laying the foundation among Arab societies for a religious revival that continues to the present. Shi’a and Sunni communities—the former in reaction to the Iranian Revolution in 1979 and the latter in response to the developing power of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt—began to associate their long-established religious beliefs and practices with personal identity, supplanting a largely manufactured and fragile loyalty to the relatively new phenomenon of the nation state.”(17)

These frameworks of analysis can be promising in the study of both Islamic religiosity as mainstream balance between civil state and mosque in moderate societies, and Islamist religiosity as an exclusive and puritan models of Wahhabism, Qaeedism, Daeshism and other trends of Jihadism in Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Syria, and Libya. The associational, communal, doctrinal, and devotional drivers of these radical Islamisms are necessary to dissect the momentum of these militant groups, not solely in their relationship with holy textbook, but also in their political and ideological dimensions. As a result, the religious-political connection has become a strategic asset in public life. Shlomo Ben-Ami, vice-president of the Toledo International Center for Peace, has recently proposed a revealing example of Iraq as a Middle Eastern country that is “choosing politics over religion.” He noticed Muqtada al-Sadr, the fiery Shia cleric who previously led deadly attacks against US troops, is now emerging as America’s best hope of containing Iran’s expanding influence in Iraq.” (18)

In retrospect, one can argue this has been an era of engineering a prototype of political Islamists, who believes in not only the sanctity and religiosity of their beliefs, but also in solidifying their political view as a trajectory of their religiosity for reshaping identities and reorganizing society. According to them, the spread of a militant or intolerant discourse is logical by necessity, and even the use of violence becomes a ‘noble tool’ for achieving a ‘noble cause’. This justification implies the attachment to their religious-cultural filters. This brings us to the question: why Arabs resort to violence; and why some analysts have argued for a correlation between Islam, Arab culture, and Arab violence in a post-911, post-Iraq War, and post-uprising Middle East.

I have come across all sorts of interpretations and misinterpretations. One provocative opinion essay published last year had the title “Are the Arabs violent because they’re religious or religious so they’re less violent?” The author argued, “The genius of religion is that it overcomes tribalism. It universalizes certain key principles and thereby achieves a greater unity. So, who clings to religion most? Peoples who are deeply fractious and have a tendency to resolve their differences through extra-judicial killings.” (19)

One of the promoters of the hypothesis of a violence-inspired Arab culture is Lee Smith who spent several years in the Middle East. In his new book “The Strong Horse: Power, Politics, and the Clash of Arab Civilizations”, he argues “violence is central to the politics, society, and culture of the Arabic-speaking Middle East, and that Arab politics is driven by the ‘strong horse’ principle.” (20) Smith builds his argument on Osama bin Laden’s assertion that “When people see a strong horse and a weak horse, by nature they will like the strong horse.” (21) However, Smith’s argument seems to be an overstretched projection of Samuel Huntington’s controversial clash-of-Civilizations concept.

The second part of Dr. Cherkaoui’s lecture will be posted soon.

|

| From left: Mohammed Cherkaoui, George Tamer, Chair and Mohammed Nekroumi, Professor at Friedrich-Alexander-University Erlangen-Nürnberg. [Al Jazeera] |

(1) The White House, “Remarks by President Trump to the 73rd Session of the United Nations General Assembly - New York, NY”, September 25, 2018 https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefings-statements/remarks-president-trump-73rd-session-united-nations-general-assembly-new-york-ny/

(2) Associated Press, “Sudan urges UN to double South Sudan regional force,” October 2, 2018 https://www.news24.com/Africa/News/sudan-urges-un-to-double-south-sudan-regional-force-20181001

(3) Sondos Asem, “Tunisia's political deals: How new power bloc may shift government balance”, Middle East Eye, October 1, 2018 https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/tunisia-%20alliance-government-power-nida-tounes-ennahda-essebsi-chahed-1897796065

(4) Sondos Asem, “Tunisia's political deals: How new power bloc may shift government balance”, Middle East Eye, October 1, 2018 https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/tunisia-%20alliance-government-power-nida-tounes-ennahda-essebsi-chahed-1897796065

(5) Sondos Asem, “Tunisia's political deals: How new power bloc may shift government balance”, Middle East Eye, October 1, 2018 https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/tunisia-%20alliance-government-power-nida-tounes-ennahda-essebsi-chahed-1897796065

(6) Robert Looney, “Does Algeria Still Have Time to Turn it Around?”, Sept. 23 2016 http://foreignpolicy.com/2016/09/23/does-algeria-still-have-time-to-turn-it-around-bouteflika/

(7) Ahmed Marwane, “A Fifth Presidential Term for Bouteflika?”The Washington Insititute, July 19, 2018 https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/fikraforum/view/a-fifth-presidential-term-for-bouteflika

(8) Wagdy Sawahel, “Protests as government shuts down Islamic HE institutions”, University World News, October 2, 2018, Issue No: 523 http://www.universityworldnews.com/article.php?story=20181001110432753

(9) Fragile States Index, 2018 http://fundforpeace.org/fsi/data/

(10) Holdcroft, Barbara (September 2006). "What is Religiosity?". Catholic Education: A Journal of Inquiry and Practice. 10 (1): 89–103.

(11) Lenski, Gerhard. The Religious factor. Garden City, NY: Doubleday. 1963

(12) Chaves, Mark (March 2010). "SSSR Presidential Address Rain Dances in the Dry Season: Overcoming the Religious Congruence Fallacy". Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 49 (1): 1–14

(13) The Institute for Economics and Peace “A Global Statistical Analysis on the Empirical Link between Peace and Religion”, http://economicsandpeace.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/Peace-and-Religion-Report.pdf

(14) David R. Smock, “Religious Contributions to Peacemaking: When Religion Brings Peace, Not War”, Peaceworks No. 55, USIP, January 1, 2006

(15) Claudia Keller, “We can learn a lot from religions”, How Germany ticks, https://www.deutschland.de/en/topic/politics/how-religions-can-promote-peace-conference-in-berlin

(16) Glock, C. Y., & Stark, R. (1965). Religion and society in tension. San Francisco: Rand McNally. P. 20

(17) Geneive Abdo, “Egypt: The Religious Root of Conflicts in the Middle East”, Pulitzer Center, February 5, 2017 https://pulitzercenter.org/reporting/egypt-religious-root-conflicts-middle-east

(18) Shlomo Ben-Ami, “The political decline of religion in the Middle East”, The Strategist, June 25, 2018 https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/the-political-decline-of-religion-in-the-middle-east/

(19) Hunter Maats, “Are the Arabs violent because they’re religious or religious so they’re less violent?” February 24, 2017 https://medium.com/mixed-mental-arts/are-the-arabs-violent-because-theyre-religious-or-religious-so-they-re-less-violent-66771abf54f9

(20) Lee Smith, “The Strong Horse: Power, Politics, and the Clash of Arab Civilizations”, Doubleday, 2010

(21) Lee Smith, “The Strong Horse: Power, Politics, and the Clash of Arab Civilizations”, Doubleday, 2010