The commander of Operation Dignity, Khalifa Haftar, shocked supporters even more than his opponents when he agreed to meet the Chairman of the Presidential Council, Fayez al-Sarraj, in Abu Dhabi on 2 May 2017, having previously refused to recognise him. This about-face may be attributable to the acquiescence of Haftar’s regional allies to direct international pressure.

Reactions to the rapprochement between al-Sarraj and Haftar varied across the eastern and western fronts. Khalifa Haftar’s status in the east precludes serious opposition to his decisions, while in the western region a substantial segment of the population blessed the meeting in hopes that a détente would stop the deterioration of the security and economic situation. In contrast, western political and military factions were incensed, and some responded violently.

Haftar’s acceptance of consensual agreement and reconciliation clearly grows out the waning possibility of assuming control of the country through decisive military action. From his standpoint, it therefore makes sense to attempt to impose his conditions through negotiations, which means the Skhirat agreement could collapse or undergo radical revisions.

Introduction

The commander of Operation Dignity, Khalifa Haftar, shocked supporters even more than his opponents when he agreed to meet the Chairman of the Presidential Council, Fayez al-Sarraj, in Abu Dhabi on 2 May 2017, having previously refused to recognise him. This about-face may come as a result of acquiescence to direct international pressure by Haftar’s regional allies.

Haftar’s statements about the Presidential Council, from the time of its inception and its entry into Tripoli in March 2017, were not at all positive. In fact, he described the accord as folly, saying that the Skhirat agreement could not build a state, but would be the cause of Libya’s destruction. For Haftar, the agreement promised reconciliation in name only and opened the door to foreign interference in Libyan internal affairs.

Haftar clung to his rejection of reconciliation and political agreement throughout the negotiations and even after the Skhirat agreement was signed and important international capitals threw their support behind it. He refused to meet Fayez al-Sarraj, the Chairman of the Presidential Council, when both of them were in Cairo in February 2017 at the invitation of the Egyptian government. Al-Sarraj sought to bring Haftar into the political agreement after the international community had recognised the Presidential Council as the sole representative of the executive authority in Libya.

Haftar failed to impose his authority with the force of arms and exacerbated the deteriorating conditions in Libya. This spurred increased pressure on him to yield to the internationally supported political accord and led Cairo and Abu Dhabi to back down from their unlimited and unconditional support for Haftar.

The basis of rapprochement

It has become clear to all domestic and foreign observers of Libya that the intransigence of the head of the parliament and the army commander subordinate to him are the main obstacle to the success of the political agreement and the principal cause of the ineffectiveness of the Presidential Council and its government. Opponents of the agreement in the western region limited themselves to criticism and did nothing for the first six months after the Presidential Council assumed the reins of power. Even action by Khalifa al-Ghawil, the Head of the National Salvation Government, was limited and contained. Obstruction from the parliament and army remained the prime cause of the weakness of the accord.

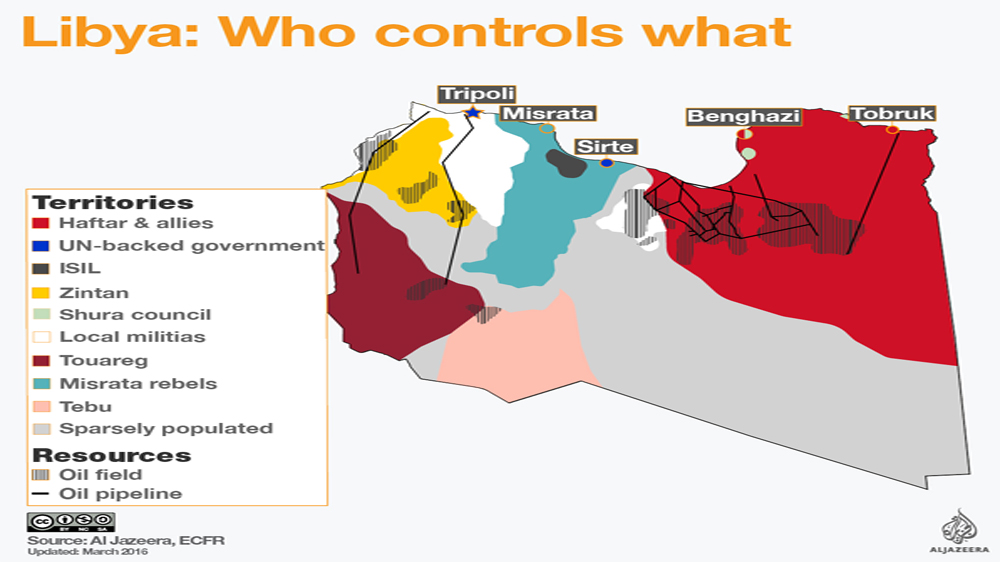

Since launching Operation Dignity in mid-2014, Haftar bet on the military option as a means of imposing facts on the ground that would change the rules of the political game in his favour. He managed to take control of the oil terminals in central Libya, succeeded in putting his loyalists in control in the southern capital of Sabha, and wasted no effort to win over paramilitary groups in Tripoli and its southwest environs. And he remained fixed on the need to take Tripoli by force of arms.

But despite the passage of three years and the massive human toll and other losses in the Benghazi war, Haftar did not succeed in taking the most important position of the Shura Council of the Benghazi Revolutionaries: the central city and its immediate environs.

The long duration of the war and its attendant casualties also fractured Operation Dignity fighting forces. Many field officers broke away, accusing Haftar of stalling and putting fighters in harm’s way without adequate support. Field commander Colonel al-Mahdi al-Barghathi defected to the other side, becoming Minister of Defence in the Government of National Accord and running military operations against Haftar and his forces, including Operation Return to Benghazi, carried out by the Benghazi Defence Brigades, and Operation Promised Hope, to confront the southern offensive led by General Mohamed bin Nail, who is allied with Haftar.

The form of reconciliation

The parties who met in Abu Dhabi did not issue a joint statement indicating the terms they had agreed upon. Citing special sources, some media outlets reported that the two sides agreed on:

- The annulment of Article 8 of the political agreement, which excludes Haftar from political and security positions

- The restructuring of the Presidential Council of the accord government

- The unification of the army and action to develop it

- The unity of Libyan territory and opposition to partition plans

- A rejection of foreign interference

- Fighting terrorism

The same sources said it was agreed to form a separate government independent of the Presidential Council and to respect court rulings. There was also a consensus on addressing displaced persons and resolving the crisis in the south.

The media also reported that the two sides agreed to hold presidential and parliamentary elections no later than March 2018.

Repercussions of the rapprochement

Reactions to the Sarraj-Haftar rapprochement differed across the western and eastern fronts. In the east, Khalifa Haftar’s position precludes any serious opposition to his decisions, even if they contradict previous statements or claims made to his supporters.

In the western region, the reactions varied due to the wider margin for freedom of expression. A broad segment of the population welcomed the meeting in the hope that a reconciliation could halt further deterioration of the economic and security situation, while political and military factions were outraged and some reacted with violence. In response to the meeting in Abu Dhabi and a potential role for Haftar in a new political arrangement, a brigade in the Friday Market area moved armed forces toward the Presidential Council. In March 2017, a brigade from the same area had attacked the Abu Sitta Base, used by the Presidential Council as its headquarters, in an angry response to statements from Haftar that he was determined to enter the capital. In the wake of that, the council was compelled to issue a statement condemning Haftar’s statements.

Similarly, army officers in the western and southern regions rejected the reconciliation between Haftar and al-Sarraj and statements from Mohamed Siala, the foreign minister of the accord government, who had recognised Haftar as the General Commander of the army. The officers met in Zuwara on 7 May 2017 to declare their refusal to recognise Haftar’s leadership of the army, calling his forces a band of lawbreakers; they were supported in this stance by political activists and civic organisations.

Prospects for the agreement

It is clear that Haftar’s acceptance of consensual agreement and reconciliation comes from a realisation that military action is unlikely to deliver control of the country. From his standpoint, it therefore makes sense to attempt to impose his conditions through negotiations, which means the Skhirat agreement could collapse or undergo the radical revisions that Haftar’s allies in the east are pressing for and which were previously raised by Ahmed Mismari, the official spokesman for the Libyan National Army.

If Haftar is compelled to opt for a negotiated resolution, obstacles remain. There is vociferous opposition to Haftar’s inclusion in the political process and the way he has exploited the tattered political, security and economic situation to cling to power. Al-Sarraj’s capitulation to Haftar’s terms could also stoke the anger present in several areas of Libya and increase tensions in Tripoli, potentially precipitating open clashes.

Moreover, the precarious situation and Haftar’s focus on the capital at the expense of settling conflicts in the eastern region, which has suffered enormously in the past three years, could spur his opponents in the east to mobilise against him on the basis of local and tribal loyalties, exploiting the shift in his position on the accord. It is under the general banner of his opposition to the accord that Haftar has created his own front, and any backtracking could lead to fractures within it.

These obstacles suggest other possible motives for Haftar’s abandonment of his previous stance on the Skhirat agreement and the Presidential Council. He could be feigning acceptance of the agreement to gain some breathing room and evade regional and international pressure, in which case he will return to his militant positions and a reliance on military force as soon as the opportunity presents itself and the pressure is lifted. Or Haftar could be gambling on a truce to pave the way for presidential elections, calculating that his chances of election are good. In this way, he would achieve his goal through peaceful means that meet with local support and foreign backing.

As for the accord government, its concessions to Haftar may spark a mutiny among the various political and military factions that back it in Tripoli, Misrata or the south. The offensive launched by pro-accord government troops on Haftar’s forces in Brak in Wadi al-Shati’ in the south on 18 May 2017, without a green light from the Presidential Council, may be a harbinger of things to come. In that case, the Presidential Council will be forced to abandon the agreement, wholly or partially, or enter into an armed confrontation that does not serve its interests. Alternatively, it could shift its position in the eastern region to seek protection with Haftar, thus risking the loss of its genuine support in western and southern Libya.