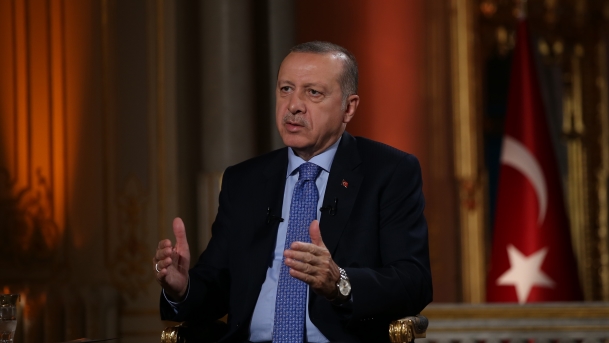

On 18 April 18 2018, Devlet Bahceli, the head of Turkey’s Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) met with President Recep Tayyip Erdogan. Erdogan came out of the meeting to announce that he had agreed with Bahceli’s proposal to hold early national elections and set the date for 24 June 2018.

Although traditionally an ultranationalist, secularist party, the MHP in recent years has forged a parliamentary alliance with Erdogan’s Justice and Development Party (AKP), and the two parties have grown closer since the failed coup of July 2016. The MHP supported the constitutional amendments in the referendum of April 2017 that reshaped Turkey’s political system as a presidential one. The presidential and parliamentary elections now scheduled in a little more than two months are the first since those amendments and will complete the country’s transition to a presidential system.

Bahceli’s desire for early elections is understandable. He hopes to maintain the MHP’s parliamentary presence through its alliance with the AKP, but his primary fear is the new IYI party, a splinter of the MHP that peeled off several party leaders and parliamentarians and competes with it for conservative, nationalist voters. But the IYI does not yet have deep roots and may be disadvantaged by Turkey’s electoral law, which allows parties to compete in elections only if they have active branches in at least half of the country’s provinces. For Bahceli and the MHP, then, the sooner the elections come the better.

Erdogan has his own reasons for wanting early elections. For one, he is considering the state of the Turkish economy. While growth in Turkey was the highest among the G20 nations in 2017, the deficit and inflation remain high and the Turkish lira continues to depreciate steeply next to the dollar and euro. Erdogan believes some of these economic woes stem from uncertainty among businessmen and foreign investors; and that a speedier transition to the new presidential system will allay this uncertainty and stabilise the situation.

Erdogan also has his eye on the larger regional context. Turkish military operations in the northern Syrian city of Afrin have mobilised the public behind the government and the AKP, and Erdogan’s party hopes to capitalise on this positive sentiment before it fades.

However if early elections make sense to Erdogan and the AKP, what challenges face them? On the parliamentary side, the question is whether the AKP can preserve its majority from the 2015 elections. The AKP’s alliance with the MHP and the rising nationalist discourse among AKP leaders over the past two years have eroded the AKP’s Islamist base and alienated the Kurdish conservative voting bloc that typically supports it. No one knows how this will play out at the ballot box and whether MHP voters can make up the difference. Even if Erdogan keeps the presidency, without a parliamentary majority he will find it difficult to push through his program in light of the severe polarization of Turkish politics.

The presidential race also presents its own difficulties. Thus far the only other presidential candidate is the head of the IYI. Whether and who the Republican People’s Party (CHP), the main opposition, will field as a candidate is still up in the air. More worrisome for Erdogan are reports that former president and an AKP founder, Abdullah Gul, is considering a run. Sources say that Gul may be loath to precipitate a split within the conservative camp and directly take on his former comrade, but he has reportedly received backing from important AKP veterans, who are attempting to mobilise all opposition parties, including the CHP, behind him.

Even if Gul declines to run, Erdogan wants to avoid a presidential run-off, which may raise doubts about his popularity and hold on power. To clear the 50-percent vote hurdle in the first round, he needs the middle-class conservatives who did not support the 2017 constitutional amendments, as well sufficient conservative Kurdish voters, or to make it up with the nationalist vote.

If Erdogan wins, it is likely to usher in a period of greater institutional stability in Turkey, making clear where the centre of decision-making lies. If, however, Gul runs and ultimately wins, particularly if the AKP keeps its parliamentary majority, the opposite is true and Turks may find themselves returning to the polls sooner rather than later.

*This is a summary of a policy brief originally written in Arabic, available here: http://studies.aljazeera.net/ar/positionestimate/2018/04/180422140105938.html.