Palestine had an indelible imprint on the 1978-79 revolution in Iran and its global vision. From the outset, when Ayatollah Khomeini, the first Supreme Leader of Iran and the main leader of the Iranian revolution, staged a revolt from within the clerical establishment in the early 1960s, the Zionist occupation of Palestine and Israel’s ties with the Shah, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, were central to his revolutionary struggle. Under Pahlavi, Iran maintained cordial relations with Israel and was wary of the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) and Arab nationalist regimes. After 1970, as the Palestinian presence in Lebanon was growing, armed resistance against the Shah’s regime arose in Iran. Many Iranian groups, some Islamist and some Marxist–Leninist, established contact with the PLO with a view to having their fighters trained in Palestinian camps in Lebanon and Syria. (1) In 1968, Ayatollah Khomeini issued a religious decree in support of the Palestinian fedayeen guerrilla forces, allowing his Shi’a Muslim followers to donate zakat (alms) to them. (2) During the 1970s, Fatah, which was the dominant faction of the PLO, emerged as a crucial node in the transnational anti-Shah movement. It embraced the Iranian leftist and clerical revolutionaries and provided expertise, training and connections with liberation fighters from around the globe.

This paper explores the relationship that pro-Khomeini activists cultivated with Fatah in the 1970s to illuminate how their transnational bonds influenced the 1978-79 revolution and the formation of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) in 1979. The Palestinian revolution, which was central to the Third World liberation, inspired and influenced the global vision of many cofounders of the IRGC. Fatah played a key role in advancing the transnational movement loyal to Khomeini and became a significant resource in the initial stage of the establishment of the IRGC. To examine the transnational engagement and connections between Iranian revolutionary clerics and the PLO, this paper brings to the spotlight the story of the internationalist revolutionary, Shaykh Mohammad Montazeri.

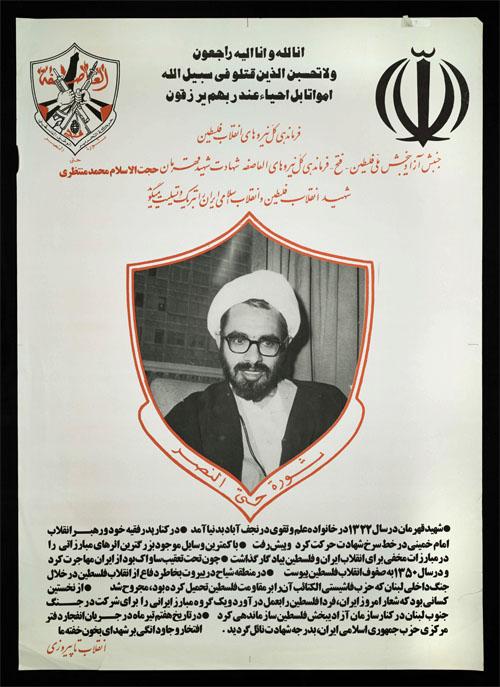

Mohammad Montazeri (henceforth Mohammad, as he was known among his followers) was a young cleric from Najafabad, a small city near Isfahan in Iran. His father, Ayatollah Hossein Ali Montazeri, was one of the close disciples of Ayatollah Khomeini and a leading figure in the 1978-79 revolution. Mohammad built a transnational network of insurrectionary activists and clerics in the years before the revolution and was a prominent advocate of the international Islamist movement. His revolutionary struggle in and outside Iran formed the prelude to the globalisation of the IRGC, posthumously turning him into what his adherents still remember: the international martyr, or shahid-i baynulmillal. Mohammad, known for his devotion to the liberation movements, had such a popular standing among Palestinian fighters that after his death in 1981, Fatah exalted him as a martyr and hero of the Palestinian revolution. Fateh’s commemoration poster (Fig. 1) read:

The Palestinian National Liberation Movement, the General Command, the forces of al-Asifa congratulates and expresses their condolences for the martyrdom of the hero, Hojat al-Islam Mohammad Montazeri, the martyr of the Palestinian Revolution and the Islamic Revolution of Iran.

Through a micro-history of Mohammad and his circle of activists and friends, this paper examines the Third Worldist roots of the 1978-79 revolution and the trajectory of relations between pro-Khomeini clergy and Fatah. While the IRGC is often understood as a Shiʿa military entity, it shows the significance of Third World ideas and connections in the creation and globalisation of this military organisation. Therefore, this paper questions the Shiʿa-centric and sectarian narratives that neglect or downplay the Third Worldist and pan-Islamic dimensions of the 1978-79 revolution. (3)

A Roving Revolutionary

Mohammad’s transnational interests began in Iran, before going to exile in 1971. As a young seminary student in the early 1960s, he became engaged in Khomeini’s movement and dedicated himself to anti-Shah activism, developing a passion for the Palestinian cause. He devoted himself to politicising fellow seminary students in Qom and Isfahan and increasing their awareness of issues that were typically ignored, even banned, at seminaries. “We had to listen secretly to radio news programmes,” recounts one of his schoolmates. (4) Economics, history of anti-colonial struggles and global politics, particularly developments in Palestine, were of great interest to him. He began teaching economics at Fayzieh, the most prestigious seminary school in Qom, and encouraged students to learn modern Arabic and English and read about both global and national politics. “We sat and thought about how we would engage the seminary students in politics and activism,” says one of his seminary colleagues. “We decided to sell them cheap two wave transistor radios that could be tuned to the Egyptian radio station, Sawt al-Arab, to listen to news about Palestine.” (5) Many students, mostly from poor backgrounds, were drawn to politics through the books and magazines that Mohammad lent them. He had a small mobile library with books on the Algerian, Egyptian and Vietnamese revolutions, and the history of the Muslim Brotherhood. (6) His activities to encourage political engagement within Qom and Isfahan seminaries, known to be averse to activism, and mobilise the theology students behind Ayatollah Khomeini landed him in prison in Iran, where he suffered severe torture. (7)

Mohammad’s seminary studies in Qom took place during the heyday of late Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser, whose influence in the region had unnerved the Shah and other Middle Eastern monarchs. Mohammad and his associates stealthily listened to Sawt al-Arab, the popular radio station of Nasser’s Egypt, for news and analysis on regional developments. “We were all crying when Nasser died,” one of Mohammad’s followers wrote in prison about his deep appreciation for the former Egyptian leader, adding that what was “especially captivating and fascinating” was the Palestinian struggle. (8)

In May or June 1971, Mohammad slipped into Pakistan to begin a long self-exile which took him to Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Bahrain, Kuwait and Europe. Pakistan, primarily Karachi, was a key base for Iranian activists, because it was, as one of his associates describes, the closest, easiest and the most inexpensive location for those who escaped the Bureau for Intelligence and Security of the State (SAVAK), the notorious secret police of the Shah. (9) The PLO office in Karachi was an initial pathway to the Fatah leadership. (10) Nearly a year into his exile, Mohammad left for Iraq, where he developed relationships with Lebanese and Iraqis in Najaf. They formed a committee in solidarity with Fatah. (11) Additionally, Mohammad established the Iranian Combatant Clergy Abroad, which, according to its statements, aimed to foster solidarity with Palestinians. (12)

In exile, Mohammad was constantly roving, often using forged passports and visas, to make new relationships, acquire resources, transfer arms to anti-Shah groups in Iran, and financed and facilitated the operations and movements of both Iranian and non-Iranian activists across the region, and even into Europe. The PLO was central to Mohammad’s network, which included Iranians who became cofounders of the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps after 1979. During the 1970s, they all went through guerrilla training in Palestinian camps in Lebanon and Syria, where they established close ties with Fatah. In the words of one loyalist, “the origin of military training of many commanders of the IRGC and forces that had a role in the Revolution, was the martyr Mohammad Montazeri.” (13)

Mohammad’s Pro-Palestinian Circle

As Mohammad developed in exile close bonds with guerrilla fighters and insurgents from the Global South, among them Islamists and leftists from Afghanistan, the Philippines, Eritrea, Palestine, Lebanon, Bahrain, Saudi Arabia and Iraq, he emerged as the key link between the anti-Shah dissidents and Fatah. During the 1970s, Mohammad brought many Iranians – his estimate was “more than a thousand of Iranian brothers and sisters” – to Lebanon and Syria, where they resided in the Palestinian camps and received military training from the Fatah fighters. (14)

One of the well-known individuals in Mohammad’s circle was Abbas Aqa-Zamani, who became the IRGC commander in 1980. Since 1970, Aqa-Zamani had worked closely with Mohammad in Lebanon. Aqa-Zamani’s sobriquet, Abu Sharif, was inherited from the time when he resided in Bourj al-Barajneh camp between 1970-1979. It was not uncommon at that time for Palestinians to give their Iranian comrades nicknames, starting with the prefix, Abu. Abu Sharif set up a network in the Palestinian refugee camp, which is located in the southern suburb of Beirut, to recruit Iranians for military training in the Palestinian camps. (15) (See Fig. 2.) Later, as a founding member of the IRGC, he continued cooperation with Mohammad Montazeri to promote the Islamic Revolution abroad.

Another individual was a prominent female guerrilla, Marzieh Hadidchi (Dabbagh), who collaborated with Mohammad in Iran. After fleeing from SAVAK in 1972, she received training in PLO camps in Lebanon and Syria. She spent more than six months with Palestinian fighters in southern Lebanon, taking part in raids against Israeli forces and later becoming a trainer herself. After the overthrow of the Shah, she played a role in the negotiations forming the IRGC and became a regional IRGC commander. (16)

Apart from these individuals, Mohammad Gharazi, the former Minister of Post and Telegraph; Sayyid Serajeddin Musavi, the former head of the Islamic Revolution Committees and former ambassador to Pakistan; and Sayyid Yahya Rahim Safavi, who was the IRGC commander from 1997 to 2007, were working with Mohammad in the 1970s. All of them went to Syria and Lebanon through his network and resided in Fatah camps for training in guerrilla warfare. (17) Indeed Mohammad was regarded by Khomeini loyalists as the primary access point to the PLO. The majority of them who went to Lebanon in the 1970s for guerilla training were received and organised by Mohammad and his associates. Fatah, which sat at the intersection of many Third World liberation struggles from Algeria and Eritrea to Southeast Asia, was a central node in this transnational network. In the eyes of the revolutionary Iranians, Fatah was at the forefront of a national liberation war and an Islamic struggle to liberate Jerusalem, the first qibla for every Muslim.

The Significance of the Palestinian Cause and Fatah

Palestine was central to the revolution’s global vision, which was influenced by anti-colonial pan-Islamism and Third Worldist solidarity. Clerical revolutionaries in Iran were inspired by pan-Islamists, like Sayyid Jamaluddin al-Afghani and Hassan al-Banna, and advocated the unification of Muslims against imperialism. Palestine, as an Islamic ecumenical cause, was at the heart of the unification to which revolutionary clerics aspired. The 1978-79 revolution was also imbued with Third World solidarity. Iranian revolutionaries found lessons and rejoiced in the struggles of Ahmed Ben Bella of Algeria, Patrice Lumumba of the Republic of Congo, and Gamal Abdel Nasser of Egypt against colonialism and neocolonialism. Palestine was at the intersection of these liberation struggles and the ecumenical vision of clerical revolutionaries. It was a struggle “at the core of the conflict between Islam and the global arrogance (Istikbar-i Jahani/al-istikbar al-ʿalami, i.e. imperialism).” (18)

To Ayatollah Khomeini and his followers, Israel was a colonial entity “planted in the heart of the Islamic world”. (19) Its occupation of Muslim lands, including the al-Aqsa Mosque, along with its oppression of Palestinians and other people of the region, imposed a duty on Muslims to defend their beliefs and land. Israel’s close relationship with the Shah made him complicit in the oppression of Muslims, both in Iran and Palestine. Khomeini argued that Israel had occupied the predominantly Muslim land of Palestine and that the Shah’s actions, particularly recognising Palestine’s occupation and supporting the Zionist regime, endangered Iran’s Islamic identity. (20) Backing the Palestinian fedayeen guerrilla forces and establishing ties with the PLO were therefore in line with this deep belief in unifying Muslims against colonialism, Zionism and tyranny.

Beyond the ideological weight, the importance of the PLO stemmed from operational and practical considerations. Within the PLO, Fatah stood out at the apex of the organisation for its strong leadership, resources, skilled cadres and all-encompassing ideology. Since the late 1950s, Fatah’s networks had expanded through the Palestinian diaspora across the region and beyond. (21) Under the leadership of experienced commanders such as Yasser Arafat (also known as Abu Ammar) and Khalil al-Wazir (also known as Abu Jihad), the movement had reached by the mid-1970s such a level in the Arab world that its leadership was “able to deal with Arab heads of state face to face, even allowing themselves in private to patronise newcomers to the Arab scene, such as Colonel Qaddafi.” (22) Unlike the Marxist factions within the PLO, the pragmatism of Fatah had allowed its leadership to embrace a wide range of Iranian opposition from Marxist–Leninists to Islamists. (23) During the 1970s, pro-Khomeini clerics established a close working relationship with the movement’s commanders, particularly Abu Jihad, who had an Muslim Brotherhood background and was, according to Khomeini’s acolytes, an observant Muslim. (24)

Fatah, at the height of its global influence in the 1970s, not only provided military expertise, but also shared intelligence, passport and visa forgery techniques, and its broad network and links to pan-Arab, pan-African and anti-imperialist activists within the anti-Shah opposition. (25) “Palestinians had a deep knowledge of the region and Arab governments, and this was one of the values of working with them,” explains an associate of Mohammad. (26) Iranians translated into Farsi PLO’s booklets on guerrilla tactics or improvised explosive devices, as well as books, such as Munir Shafiq’s Topics from the Palestinian Experience, concerning the principles of partisan activism and maintaining secrecy, and Ethics of the Revolutionary Fighter. (27) In the beginning, the IRGC relied on some of these translations to train its cadre for civil warfare and the war against the Iraqi invasion of Iran. (28)

The Pro-Palestinian Faction Inside the Revolution

In their ardent belief in liberation movements, Mohammad’s revolutionary loyalists and friends formed a pro-Palestinian core within the IRGC. In the twilight of the Pahlavi monarchy, they began to organise and establish what became officially on 21 April 1979 the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps. They deployed their connections with the PLO and the military training that they gained in Palestinian camps in the 1970s to build influence in the IRGC. This unfolded in competition with a militia that liberals in the provisional government had formed to take the lead and control of the IRGC. As Abu Sharif recounts, “the provisional government did not have trained competent forces. They brought a few militants from the Shah police and army. But we had well trained individuals who received training from Lebanon and had witnessed the war zone.” (29)

Soon after returning from exile, Mohammad reached out to the Fatah leadership for the organisation and training of his militia. (30) The PLO chief, who called him “Abu Ahmad”, gathered around forty Palestinian militants and brought them to Tehran. However, facing technical difficulties, they did not do much on the ground and left after a while. (31) Mohammad and his associates held many meetings with the PLO officers to discuss issues related to training and organisation. (32) He was even in favour of assigning key posts of the IRGC to Palestinians. (33) Soon the frictions between the pro-Palestinian faction and the liberals in the provisional government began to grow, turning the relationship with the PLO into a major factional issue in the early months of the revolution.

From February to November 1979, the provisional government of Mehdi Bazargan ruled the country along, and in competition with, the Islamic Revolutionary Council (Shura-yi Inqilab-i Islami), which was predominantly under the influence of anti-Bazargan clerics. Liberals held key positions in the provisional government. Many of them were members of the Freedom Movement of Iran, Nehzat-i Azadi-yi Iran. (34) They had gained significant experience in Lebanon and established cordial ties with the Amal Movement and its founder, Sayyid Musa Sadr, tracing back to the 1960s and 1970s. Under Bazargan, liberals along with several conservative figures were in favour of close relations with the Amal Movement. (35) Shortly after the Revolution, the pro-Amal approach of the Bazargan government collided with the pro-Palestinian faction. This faction and the PLO alike viewed Bazargan’s unfriendly stance toward Yasser Arafat as a reflection of Amal’s influence in the provisional government.

The provisional government and the Amal Movement wanted to deny Palestinians, and particularly Fatah, the fruits of their past cooperation with the Iranian opposition. As Mustafa Dirani, a former military commander of Amal and later Hezbollah, describes Amal’s view at the time: “Palestinians had trained Iranians in the camps and they used this connection to influence the trends in Iran to that end.” (36) When the PLO leader, within the first few days of the fall of the Shah, proposed the idea of visiting Tehran, provisional government officials discouraged him. If it was not for personal connections with Mohammad Montazeri, he could not have become the first foreign leader hosted by revolutionary Iran. (37)

In February 1979, Arafat arrived in Tehran with a top political, military and intelligence delegation, including Abu Jihad and Hani al-Hassan. (38) The latter, the right-hand man of Arafat, was to become the Palestinian ambassador in Tehran. Mohammad hosted Hassan and his staff and placed his own guards in charge of protecting the Palestinians and escorting them around the country. (39) According to one of Mohammad’s associates in the IRGC, “the late Mohammad had a high trust in the capabilities and skills of Hani al-Hassan. He was saying that the Palestinians had dispatched one of their best and powerful cadres to us.” (40)

Liberals were not happy with Arafat’s arrival, the person they blamed for the troubles of their ally in Lebanon and the conflict between the Syrian-backed Amal Movement and the Palestinians. (41) In the eyes of Ibrahim Yazdi, who was the foreign minister in the provisional government, Arafat had failed to rein in the extremes of fedayeen and thus was responsible for the suffering of the Shiʿa in the south of Lebanon. If it were not for the PLO and its Lebanese allies in the Lebanese National Movement, Yazdi writes in his memoirs, Hafez al-Assad would not have had to intervene in 1976 to save the right-wing Maronites in Lebanon. (42)

It did not take the Fatah leadership in Tehran long to realise that the provisional government was standing in its way. (43) When in a press interview, the chair of PLO said that Iran had pledged material and military support for Palestinians, the provisional government issued a statement to deny Arafat’s words, because it was, according to the spokesperson of the provisional government, against the Iranian “national interests”. (44) Liberals also did not want Arafat to open any representation office in Iran.

Although Ibrahim Yazdi had joined the PLO delegation to celebrate the capture of the Israeli embassy in Tehran, the Bazargan government was against handing over the embassy to Fatah. As Sayyid Hani Fahs, who was at the time a member of Fatah and accompanied Arafat during his first visit to Tehran, says, “Yazdi had reservations about handing over the Israeli Embassy to Arafat. We were against him.” (45) Eventually, pro-Palestinians forced the provisional government to hand the Israeli embassy to Arafat. “Is this how you honour the Palestinian revolution,” Mohammad asked nationalist liberals, “which provided guerrilla training to more than a thousand Iranian brothers and sisters?” (46) Pro-Palestinians also accused liberals of shutting down the PLO representation office in Ahwaz, because, according to a U.S. embassy cable in Tehran, officials like the spokesperson of the provisional government were “most concerned about PLO activities in Khuzestan province”. (47) At the time, some liberals claimed that Palestinians were spying for Iraq and accused them of establishing ties with Arab secessionists in Khuzestan, an accusation that Fatah categorically denies.

At the same time, the Amal Movement in Lebanon accused Fatah of stirring things between Amal and Khomeini’s Iran. According to Rabab Sadr, who led the Amal Movement after the disappearance of her brother. “After Imam Musa Sadr’s [disappearance], Palestinians, and in fact Fatah, began propaganda and slander against Amal.” (48) In particular, they saw the new Palestinian embassy and ambassador Hani al-Hassan in collusion with anti-Amal Iranians to undermine the Amal Movement. (49) This was not totally unfounded. As it became clear later, for Arafat, the revolution in Iran was an important opportunity to strengthen his position both in the region and Lebanon, where an Amal-Syria alliance sought to keep him at bay. The escalating tensions over Amal and solidarity with the Palestinian revolution in Lebanon further crystallised the factional divide inside Iran between the liberals and the pro-Palestinian faction. The relationship between the two factions grew even stormier in the final days of the Bazargan government, when Mohammad organised volunteers from across Iran to send to Lebanon. Taking place at the juncture of the Lebanese Civil War, the Islamic Revolution and factionalism in Iran, this endeavour became a precursor to the revolutionary Iran’s involvement in Lebanon and a landmark in the power struggle over exporting the revolution.

Dispatching Iranian Volunteers to Lebanon

In November-December 1979, Mohammad recruited Iranian volunteers to dispatch to southern Lebanon in support of the Palestinian fedayeen. (50) Following weeks of controversy with liberals in Tehran, Mohammad and his associates were finally able to dispatch these volunteers with the assistance of their associates in Fatah and in Lebanon. However, as the volunteers’ planes touched down in Damascus, problems quickly mounted. Despite clamouring for a united front against Israel, both Syrian and PLO officials balked at the plan, wary of the consequences for the Lebanese political equation and of Israeli’s reaction in the south.

While the Lebanese government and the Amal Movement were firmly opposed to posting the Iranian volunteers in southern Lebanon, both the Syrian government and Fatah attempted to evade cooperation with Iranian internationalists in order to dissuade them from going to Lebanon. Neither Arafat nor al-Assad, who conceded stationing the volunteers in Fatah bases in Syria, yielded to Iranian pressure to open the Lebanese front to the impassioned volunteers. “Mohammad Montazeri was acting above the dominant equation in Lebanon,” says Anis al-Naqqash, a Lebanese who was a liaison between Fatah and the volunteers. “Both al-Assad and Arafat were concerned about whom they were going to side with in Lebanon.” (51)

Just a few days before the arrival of Iranian forces in Syria, the PLO spokesman in Lebanon, Abdul Muhsin Abu Mayzar, hinted that the arrival of a large number of volunteers in the south could pose a problem for the PLO and that “before combatants, we are in need of financial and political support”. (52) In early January, while tens of volunteers were stationed in Damascus and many more waited in Tehran to join them, Mohammad entered Lebanon. He went to al-Jamaʿa al-Arabiya Mosque in Beirut and held a press conference there to announce the plan. There, he quoted Ayatollah Khomeini, “Today Iran and tomorrow Palestine”, and announced that the volunteers were financially supported by the Iranian masses and would come to Lebanon to convey the Revolution’s message to the Lebanese mustadhʿafin (downtrodden). (54) “We are coming here not just to fight but also to help rebuild this country, restoring its cities, hospitals and schools,” he proclaimed. (55)

A few days after the arrival of the volunteers in Syria, their field commander met with Abu Jihad in Beirut to discuss the details of coordination between Palestinian and Iranian forces. “The outcome of our meeting was the establishment of a joint war-operation room, which was to be led by Abu Jihad and myself,” says Salman Safavi, who was appointed by Mohammad to oversee the volunteers. (56) But these were ultimately empty words. Afterward, Fatah leaders refrained from taking any further steps to facilitate the transfer of the volunteers to Lebanon. Facing Iranian persistence, Abu Jihad eventually informed the volunteers of Fatah’s definitive rejection, asserting that posting the corps was impossible because “al-Assad and the Lebanese government do not support it, and southern Lebanon’s front is silent, and we are not able to handle another war.” (57) Mohammad’s revolutionary initiative could have, as one of his Lebanese associates notes, “reshuffle[d] all the cards in the Lebanese scene”. (58) Arafat sought to benefit from it, but he and the other Fatah leaders did not wish to see an outside party involved in their actions and operations in the south. (59)

Fatah remained resistant to any collective posting of volunteers in Fatah Land, the autonomous territory of the movement in southern Lebanon. It ultimately proposed a highly modified version of what the Iranian side wanted: volunteers could enter two-by-two and be incorporated into separate Palestinian guerrilla cells in southern Lebanon. This fell short of the 15-member minimum for groups that the Iranian commanders had requested in order to join the Palestinian guerilla units. As one of the associates of Mohammad explains:

We did not want to enter [the Palestinian] groups one-by-one. This could have enervated our forces and affected our personnel’s ideology, since most Palestinian [fedayeen] were secular. Thus, we decided to leave it to the decision of the volunteers: whoever wishes to can go to Lebanon on his own and whoever wants to can go back to Iran. (60)

Aside from a handful of volunteers, the rest chose to return home.

Despite the determination and persistence of revolutionary Iranians, the mission fell short of its goals. Nevertheless, it became a unique inspiring moment for the resistance in Lebanon and laid the groundwork for future Iranian engagement in Lebanon, including the subsequent deployment of the Revolutionary Guards to the Bekaa Valley following the Israeli invasion of June 1982. As Shaikh Mohammad Khatun, a former member of Hezbollah’s Central Council, describes:

What Mohammad Montazeri did was not successful; however, it left a notable impression on some of our brothers here that the Palestinian cause is a priority for the Revolution in Iran. It also left an emotional impression on people that the Iranians came here and broke the air of submissiveness [in the face of Israel] that was prevalent in our areas. (61)

The unfulfilled endeavour revealed the limits of solidarity with the Palestinian revolution and the early signs of disagreements between Islamists in Iran and Arafat. Before long, Fatah and Iran drifted further apart due to the PLO’s stance concerning the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, the Iran-Iraq War, and the formation of the Syrian-Iranian partnership, which later overshadowed Khomeini-Arafat relations. A few years later, these consequential developments upended the friendship between Arafat and the Islamic Republic. (62)

Conclusion

Palestine was central to the Third World liberation in the Middle East. As Arafat took control of the PLO after the June 1967 war, the PLO’s fedayeen captured the attention of the anti-Shah opposition in Iran. (63) During the 1970s, PLO fighters and Iranian revolutionaries became brothers in arms. This paper demonstrated how Fatah became a key source of support for Iranian clerical revolutionaries, many of whom later assumed leadership roles within the IRGC. By tracing the revolutionary activities of Mohammad Montazeri in Iran and exile, this paper explored the connections, encounters, friendship and exchange of ideas and expertise between the pro-Khomeini revolutionaries and Fatah. The relationship with Fatah influenced the global vision of the IRGC cofounders and became instrumental, through providing transnational connections, military skills and even arms, in the establishment of the IRGC. This paper further illuminated how the relationship with Fatah cast a shadow over the post-revolution factionalism. The initially close bonds between Arafat and Khomeini began to fray and eventually the revolution shifted away from the PLO to Palestinian Islamic movements.

This shift marked a larger pivot in the locus of revolutionary power from secular Third Worldism to Islamist transnationalism. (64) 1979 ushered in a new era of resurgent Islamists, exemplified in Palestine by the emergence of Islamic Jihad and Hamas during the 1980s. (65) For this reason, the dominant scholarship widely regards the 1978-79 revolution in Iran as “the breaking point between the decades dominated by secular and left-leaning ideologies and the following decades dominated by Islamism”. (66) While much of the scholarship tends to see the relationship between the PLO and the pro-Khomeini clergy as a transient moment of solidarity and inconsequential, this paper brought into focus the significance of Fatah and Third World liberation for the pro-Khomeini movement and its lasting imprint on the formation of the IRGC. By illuminating these connections, it sought to challenge the Shiʿa-centric and sectarian narratives that overlook or downplay the Third Worldist dimensions of the 1978-79 revolution.

(1) In the 1960s and 1970s, two leftist guerrilla movements emerged in Iran: the Mojahedin-e Khalq, founded by committed Muslims, and the Fada'iyan-e Khalq, a Marxist group. On their ties with the PLO, see H. E. Chehabi, Distant Relations: Iran and Lebanon in the Last 500 Years (London: I. B. Tauris, 2006), pp. 185-190.

(2)Hamid Ruhani, Nihzat-i Imam Khomeini [The Movement of Imam Khomeini], Vol. 2 (Qom: Intisharat-i Daral-‘Ilm, 1358/1980), pp. 387-388.

(3) While the revolution had Shiʿa and nationalist components, it had deep roots in pan-Islamic and Third Worldist ideas. The revolutionary Iranian worldview emphasised the unity between different Islamic sects and, through support for the Palestinian cause, sought to create a united Islamic front against the common enemies of the umma, primarily US imperialism and Israel. This paper expands on the work of scholars like Ervand Abrahamian, Hamid Dabashi and Behrooz Ghamari-Tabrizi, who contend that the ideology of the 1978-79 revolution was not sectarian or confined to traditional Shiʿa discourse. Ervand Abrahamian, Khomeinism: Essays on the Islamic Republic (Berkeley: University of California, 1993); Hamid Dabashi, Theology of Discontent: The Ideological Foundation of the Islamic Revolution in Iran (New York: New York University Press, 1993); Behrooz Ghamari-Tabrizi, Islam and Dissent in Postrevolutionary Iran: Abdolkarim Soroush, Religious Politics and Democratic Reform (I. B. Tauris, 2008). See also, Juan R.I. Cole and Nikki R. Keddie, Shiʿism and Social Protest (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1986).

(4)Hassan Ataie, Interview by author, 3 October 2009.

(5) Sawt al-Arab (Voice of the Arabs) was the popular Arabic radio station broadcast by Nasser’s Egypt; Hassan ‘Ataie, Interview by author, 3 October 2009.

(6) Farzand-i Islam va Quran [The Scion of Islam and Quran], Vol. 2 (Tehran: Vahid-i Farhangi-i Bunyad-i Shahid, 1362/1983), pp. 1032-1033.

(7) Mahmud Vahid, Interview by author, 9 August 2008.

(8) Bunbast-i Mehdi Hashemi: Rishiha-yi Inhiraf [Mehdi Hashemi’s Dead-end: the Roots of Deviation], Vol. 1 (Isfahan: Idar-yi Kul-i Ittelaʿat-i Ustan-i Isfahan, 1377/1998), pp. 64-65. On Nasser’s influence on pro-Khomeini activistes in Iran, see: Muhammad Qubadi, Yadistan-i Dawran: Khatirat-i Hujjat Al-Islam Va-Al-Muslimin Sayyid Hadi KhaminahʹI (Tehran: Intisharat-i Surih-yi Mihr, 1400/2021), pp. 227-232.

(9) Abbas Aqa-Zamani, Interview by author, 5 November 2008.

(10) Farzand-i Islam va Quran [The Scion of Islam and Quran], Vol. 1 (Tehran: Vahid-i Farhangi-i Bunyad-i Shahid, 1362/1983), pp. 70-71.

(11) Among these were radical Lebanese like Sayyid Hani Fahs, Muhammad Saleh al-Husseini and Shaikh Muhammad Farahat; Muhammad Sadiq al-Husseini, Interview by author, 1 July 2009.

(12) Sayyid Ali Akbar Mohtashami and Sayyid Mahmud Duʿaei were members in this society, Ruhaniyat-i Mubariz-i Iran-yi Kharij az Kishvar. Asghar Jamalifar, “Jaryan Shinas-yi Hamkaran Mubarezat-yi Shahid Muhammad Montazeri” [On Shahid Muhammad Montazeri's Comrades in Struggle: An Interview with Asghar Jamalifar], Shahid-i Yaran, No. 48, (Aban 1388 - November 2009), 79-80.

(13) “Guftugu ba Asghar Jamalifar Darbareh-yi Mobarizat-i Beinolmelali-yi Mohammad Montazeri: Nemiguzashtand imam ra tabligh kunim” [Interview with Asghar Jamali about Mohammad Montazeri ’s international struggles: They prevented us from promoting the teachings of the Imam.], Iran Daily, Ramz-i Ubur, Vol. 4, Shahrivar 1389/August 2010, p. 130. Other individuals in this group were Morteza Aladpush, Ali Janati, Ahmad Movahedi, Asghar Jamali Fard, Salman Safavi, Mohammad Ali Hadi Najafabadi and Sayyid Hamid Ruhani.

(14) Farzand-i Islam va Quran, Vol. 2, p. 319.

(15) Abbas Aqa-Zamani, Interview by author, 5 November 2008.

(16) Maryam Alemzadeh, “Revolutionaries for Life: The IRGC and the Global Guerilla Movement,” in Arang Keshavarzian and Ali Mirsepassi Global 1979: Geographies and Histories of the Iranian Revolution (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021), pp. 190-193.

(17) Sayyid Yahya Rahim Safavi, Az jonub-i lubnan ta jonub-i iran [From Southern Lebanon to Southern Iran], ed. Majid Najafpur, (Tehran: Markaz-i Asnad-i Inqilab-i Islami, 1383/2005), pp. 94-97. Another pro-Palestinian was Jalaleddin Farsi whose relationship with the PLO, like Abu Sharif’s, originated from Lebanon where he resided between 1970 and 1972. See his memoirs, Jalaleddin Farsi, Zavaya-yi tarik [Dark Corners] (Tehran: 1373/1994).

(18) Ali Khazim, Tajammuʿ al-ʿUlamaʾ al-Muslimin fi Lubnan: Tajriba wa-Namudhaj [The Assembly of Muslim Scholars in Lebanon: Experience and Model] (Beirut: Dar al-Ghurba, 1997), p. 79.

(19) Amal Saad-Ghorayeb, “An Examination of the Ideological, Political and Strategic Causes of Iran’s Commitment to the Palestinian Cause”, Conflicts Forum, July 2011, p. 6, https://tinyurl.com/ms3kzwvn (accessed 27 February 2025).

(20) Seyed Ali Alavi, Iran and Palestine: Past, Present, Future (London: Routledge, 2019), p. 36.

(21) Helena Cobban, The Palestinian Liberation Organization (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984), p. 6.

(22) Ibid., p. 10.

(23) H. E. Chehabi, “The Anti-Shah Opposition and Lebanon”, in H. E. Chehabi (ed.) Distant Relations (London: I. B. Tauris, 2006), pp. 180-198.

(24) Anis al-Naqqash, Interview by author, 5 May 2010. See also: Farzand-i Islam va Quran, Vol. 2, p. 622.

(25) On Fatah’s influential status in the late 1960s and 1970s, see: Paul Thomas Chamberlin, “The PLO and the Limits of Secular Revolution, 1975–1982” in R. Joseph Parrott and Mark Atwood Lawrence (eds.), The Tricontinental Revolution: Third World Radicalism and the Cold War (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022), pp. 93-110.

(26) Hassan Ataie, Interview by author, 30 July 2008.

(27) Mawduʿat min al-Tajriba al-Filistinyya and Akhlaqiati al-Muqatil al-Thawry; Ali Jannati, Unpublished oral history interview, 19 Bahman 1374/8 February 1996, pp. 14-15.

(28) Sayyid Ali Akbar Tabataba’i, Bidun-i Marz [Without Borders], ed. Golali Babaei (Qom: Khat-i Moqadam, 1402/2023), pp. 64-65.

(29) Abbas Aqa-Zamani, Interview by author, 13 November 2008.

(30) Abbas Aqa-Zamani, Interview by author, 22 November 2008; See also: Jumhuri-yi Islami, 21 Farvardin 1358/12 April 1979.

(31) Farzand-i Islam va Quran, Vol. 1, p. 190.

(32) Sayyid Muhammad Kazim Musavi Bujnurdi, Khatirat-i Sayyid Muhammad Kazim Musavi Bujnurdi [Memoirs of Sayyid Muhammad Kazim Musavi Bujnurdi], (Tehran: Sazman-i Tablighat-i Islami, Huzeh-yi Hunari, 1378/1999), pp. 252-253; Farzand-i Islam va Quran, Vol. 2, p. 318.

(33) Mohsen Rafiqdust, who oversaw the IRGC’s logistics, coordinated with Mohammad Montazeri for the first procurement of arms for the IRGC from Fatah. “Arafat gave him 5000 Kalashnikovs for free,” recounts one of Montazeri’s acolytes; Anonymous, Interview by author, 5 October 2017.

(34) On the history and ideology of the Freedom Movement of Iran, which had been established in 1961 by Islamic students and university professors in Tehran, see: H. E. Chehabi, Iranian Politics and Religious Modernism: The Liberation Movement of Iran under the Shah and Khomeini (London: I.B. Tauris, 1990).

(35) Among these clerics were Ayatollahs Hassan Qumi and Sayyid Kazim Shariʿatmadari. See: Keyhan, 22 Ordibehsht 1358/12 May 1979.

(36) Mustafa Dirani, Interview by author, 27 February 2009.

(37) Farzand-i Islam va Quran, Vol. 1, p. 269.

(38) Sayyid Mehdi Hashemi, “Inqilab-I Baynul Millal-i Islami, Jalaseh-yi 25” [The International Islamic Revolution, Session 25], Audio recording from private collection, 1983-84, Mp3.

(39) Anonymous, Interview by author via Skype, 12 May 2018.

(40) Shaikh Mahmud Khatib, Interview by author, 25 February 2017.

(41) Farzand-i Islam va Quran, Vol. 1, p. 269.

(42) Ibrahim Yazdi, Shast sal-i saburi va shakuri: khatirat-i Duktur Ibrahim Yazdi [Sixty Years of Patience and Persistence: The Memoirs of Dr. Ibrahim Yazdi], (Tehran, Intisharat-i Kavir, 1394/2015), p. 581

(43) Hani Fahs, Muqimun fi al-Dhakira [Residing in Memory], (Damascus: Dar al-Mada, 2012), pp. 41-42.

(44) Abbas Amirentezam, An Suy-i Itiham 1, Khatirat Abbas Amirentezam [Beyond Accusation 1; The Memoirs of Abbas Amirentezam], p. 32.

(45) Sayyid Hani Fahs, Interview by author, 1 May 2010.

(46) Farzand-i Islam va Quran, Vol. 2, p. 319.

(47) U.S. Embassy in Tehran, “Mohammad Montazeri,” Wikileaks, 25 July 1979, https://tinyurl.com/y3fza8wn.

(48) Rabab Sadr, Interview by author, 22 April 2010.

(49) Atef Aoun, Interview by author, 4 November 2009.

(50) The plan was to recruit 1080 volunteers and transport them to southern Lebanon to take part in the restoration of war-stricken areas and engage in battle alongside Palestinians against Israel. See: As-Safir, 10 December 1979.

(51) Anis al-Naqqash, Interview by author, 8 April 2008.

(52) Etelaʿat, 25 Azar 1358/16 December 1979.

(53) Anis al-Naqqash, Interview by author, 5 May 2010 and 8 April 2008.

(54) As-Safir, 3 January 1980.

(55) Ibid.

(56) Salman Safavi, Interview by author, 17 July 2010.

(57) Anis al-Naqqash, Interview by author, 5 May 2010.

(58) Anis al-Naqqash, Interview by author, 8 April 2008.

(59) An-Nahar, 14 January 1980. On Arafat’s position, an An-Nahar analyst wrote that he did not want the initiative to damage the Palestinian-Shiʿa relationship in Lebanon; An-Nahar, 21 January 1980.

(60) Hossein Mahdavi, Interview by author, 9 August 2008.

(61) Shaikh Mohammed Khatun, Interview by author, 10 September 2009.

(62) Palestinian nationalism and statist ambitions were influential within the PLO. This was one of the reasons behind the tensions between the PLO and revolutionary Iran. See: Sune Haugbølle, “The 'Ends' of the Palestinian Revolution in the Fakhani Republic” in Rasmus C. Elling and Sune Haugbolle (eds.), The Fate of Third Worldism in the Middle East: Iran, Palestine and Beyond (OneWorld Publishers, 2024), pp. 268-289. Despite Arafat’s refusal to side with Iran in the aftermath of the Iraqi invasion in 1980, the Islamic Republic hoped that it would eventually bring Arafat into its transnational orbit. For example, in May 1982, Mohtashami met Arafat in Damascus and proposed establishing a joint bank account to finance Fatah operations against Israel. According to Mohtashami, Arafat turned out to be only interested in receiving money and not undertaking a serious fight against Israel. Arafat also insisted on Iran changing course in the war with Iraq and ending it soon. Although this became the last meeting between Mohtashami and Arafat, Fatah’s ties with Iran and Hezbollah continued in the subsequent years; Sayyid Ali Akbar Mohtashami, Interview by author, 17 July 2010.

(63) Sune Haugbolle and Rasmus C. Elling, “Introduction: The Transformation of Third Worldism in the Middle East” in Rasmus C. Elling and Sune Haugbolle (eds.), The Fate of Third Worldism in the Middle East, pp. 1-26.

(64) On the shift from secular radicals to religious leaders after 1979, Paul Thomas Chamberlin, “The PLO and the Limits of Secular Revolution, 1975–1982” in R. Joseph Parrott and Mark Atwood Lawrence (eds.), The Tricontinental Revolution: Third World Radicalism and the Cold War (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2022), p. 100.

(65) Mohammad Ataie, “Brothers, Comrades, and the Quest for the Islamist International: The First Gathering of Liberation Movements in Revolutionary Iran” in Sune Haugbolle and Rasmus Elling (eds.), The Fate of Third Worldism in the Middle East, pp. 121-144.

(66) Sune Haugbolle and Rasmus C. Elling, “Introduction: The Transformation of Third Worldism in the Middle East” in Rasmus C. Elling and Sune Haugbolle (eds.), The Fate of Third Worldism in the Middle East, p. 16.