The crisis in Yemen has in recent years played a pivotal role in raising the level of tensions and confrontation between Saudi Arabia and the Iran. Moreover, in all its forms, whether directly or through proxies, it has added new dimensions to the competition and the cold war between Tehran and Riyadh in both ideological and geopolitical terms.

Yemen is a fundamental part of Saudi Arabia’s national security. For this reason, it holds a strategic place at the main core of Saudi Arabia’s political belief system. It is a country where an armed offensive by the Houthi movement in Sanaa, its capital, caused intense concerns and represented a major threat to Saudi Arabia, especially as the movement allegedly receives military, financial and security backing from Iran.

This paper examines the different levels of competition and confrontation between Iran and Saudi Arabia in Yemen, and how this competition has turned into bitter tensions that resemble a cold and harsh war between the two regional powers. It also discusses the historical dimensions of these tensions, and how Yemen constitutes strategic leverage for fundamental changes that impact the balance of power and balance of threats governing the historical competition between Riyadh and Tehran.

Parts of the paper discuss the internal and external factors that contributed to transforming Yemen to one of the most important testing grounds for crossing red lines, and how local Yemeni actors have become a mere reflection of the conflict at its regional level. Finally, the paper touches on the deciding factors that prompted Riyadh and Tehran to seriously and practically consider the possibility of ending the cold war between them, and the place Yemen holds in the bilateral agreement that was recently signed under the auspices of China.

Introduction

Former US president Richard Nixon announced in June 1969 that strategic changes have begun to take shape in US foreign policy, and called them the “Nixon Doctrine”. This new American doctrine was, as part of its broader strategy, based on the provision of economic, military and security support for its allies instead of direct military intervention. It also tried to give US allies a partial practical role in areas that were under the influence of the United States. This was concurrent with the United Kingdom’s decision to exit the Persian Gulf region in 1971, which allowed Washington to implement its new doctrine based on a policy of “twin pillars” that included the Saudi kingdom and the Iranian monarchy as US allies and strategic partners, despite the implicit regional competition between the two countries.

At that time, a variety of factors nudged Saudi Arabia and Iran toward closer ties and cooperation, including:

- Their fear of increased communist influence backed by the Soviet Union

- Increasing support of the Soviet Union for Iraq

- The rising political and cultural influence of leftist movements in the region (1)

Cooperation and closeness between Saudi Arabia and Iran, two regional powers supported by the United States, led to adequate successes in managing the foundations of political, security, military and economic relations across the Gulf region. But this trend was short-lived due to the rise of competition borne out of the lack of trust and security concerns between Riyadh and Tehran. This was evident in 1974 when Saudi Arabia questioned the Shah of Iran’s goals from two aspects:

First: The Shah’s efforts to develop his country’s military capabilities both quantitatively and qualitatively through numerous arms deals.

Second: The Shah’s military intervention in Oman during the Dhofar Rebellion, which gave him more influence in the strategic Strait of Hormuz. (2)

Several years later, after the revolution in Iran was victorious and the monarchy ended in 1979, the nature and content of relations between Riyadh and Tehran underwent significant changes, taking them from unity and cooperation to confrontation and conflict. Following the victory of the revolution in Iran, a variety of factors played a direct role in shaping relations between Saudi Arabia and Iran, including:

- The victory of the revolution in Iran led to the creation of a new political order, which consisted of an Islamic republic based on the principle of velayat-e faqih (the guardianship of an Islamic jurist) in Shia jurisprudence, which was against monarchist states in the region and Western intervention across the Middle East.

- Saudi Arabia’s political, military and economic support for Iraq against Iran during the Iran-Iraq War of 1980 to 1988

- Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait in 1990, the US-led international coalition that was formed as a result of it, and the war that began against Iraq and its then-President Saddam Hussein with the aim of liberating Kuwait

- The events of 9/11 in the United States and subsequent US policies based on direct military intervention in the region

- The US invasion of Iraq in 2003, the toppling of Saddam Hussein, change in the political regime, the transfer of power to Iraqi Shia opposition close to Tehran, and the imbalance of power that was created between Saudi Arabia and Iran as a result

- An increasing rise in the military and political power of the Islamic Republic’s allies in the region, suggested by Hezbollah’s 2006 war with Israel and Hamas’s victory in the 2005 elections

- The eruption of the Arab Spring revolutions and significant changes in the balance of power and political centres of influence in the Arab world, especially with these events extending to the area of direct Iranian influence in Syria and the area of Saudi national security in Yemen. (3)

What this paper will focus on subsequently are the events in Yemen that represented one of the main areas of direct and violent conflict between Iran and Saudi Arabia, and how Yemen will be the first gateway to any real agreement between the two countries when they decide to go from cold war to cautious peace.

Yemen caught between the influence of Saudi Arabia and Iran: No room for good will

Perhaps putting Yemen in the context of the “balance of threat” theory of Stephen Walt would make it appear a perfect model. Walt’s theory is based on the fact that the main factor deciding the security of a country lies within its ability to recognise, understand and deal with threats regardless of their actuality or size. Walt believes that security threats are a complicated matter that no state can ignore or easily overcome. Moreover, he defines a framework to understand the apparent and illicit nature of a threat:

- The geographic factor

- Offensive capabilities

- Political goals

- The reality of hostility and enmity

- The state’s resources and capabilities

In the case of Yemen, which lies in the area of conflict between Saudi Arabia and Iran, it becomes evident that the third aforementioned factor – political goals – has become a pivotal and troubling issue, especially considering an almost total lack of trust between Riyadh and Tehran. Recognising the political goals of Iran and Saudi Arabia concerning Yemen is difficult. Also, objectives change, and sometimes quickly.

Riyadh believes that Iran’s behaviour in Yemen constitutes a national security threat for Saudi Arabia, while Tehran insists that its policies in Yemen are neither offensive nor based on an aggressive approach, but deterrent first and foremost. On the other hand, Iran believes that Saudi Arabia’s moves in Yemen are the main factor behind insecurity and instability in the Gulf region, just as they are the main reason behind political and geographical fragmentation in Yemen. Both countries prefer to do away with goodwill and maintain the approach of emphasising that the other side’s policies are the real threat. Regardless of whether this reading is correct, the belief that the other side poses a threat largely governs the nature of relations in competition, conflict and fighting on Yemeni soil.

What confirms the aforementioned is Yemen’s importance in the political doctrine of Saudi Arabia in the dimensions of ideology and geopolitics versus the ideological and strategic position of Yemen for Iran. (4) Therefore, political and field developments in Yemen are an important factor in judging the expansion or decline of the areas of influence for both Saudi Arabia and Iran, especially as Yemen can be considered a suitable environment for the factors that contribute to the exacerbation of fighting between these two regional powers:

- Yemen is a weak and impoverished country with a vast geographical area.

- The existence of a suitable environment for religious and sectarian polarisation

- Yemen’s important strategic position

- The possibility of finding evidence that supports each side’s accusations against the other

- The potential for the Yemeni crisis to become a regional crisis

- The potential for the Yemeni dossier to become international (5)

All of these factors combined contribute, whether directly or indirectly, to the exacerbation of tensions between Saudi Arabia and Iran. Moreover, they play a vital role in making the influence of one of the two sides overpower that of the other.

Yemen’s position in Saudi Arabia’s foreign policy

Yemen has always been at the forefront of Saudi Arabia’s strategic interests for two important sets of reasons: geopolitics and ideology. (6)

Interest in Yemen’s political geography comes from its important geographic location, which includes the vital Bab al-Mandab Strait, connecting the Red Sea, the Gulf of Aden and the Arabian Sea to the Indian Ocean. This geographic position makes Yemen one of Saudi Arabia’s most important neighbours and has put it at the heart of Riyadh’s strategic doctrine, especially after the war of 1930 which ended with Yemen’s defeat and the signing of the Taif Agreement that demarcated borders and ended border disputes.

But the ideological-religious importance of Yemen is no lesser than its geopolitical importance in Saudi Arabia’s foreign policy. The Muslim nation of Yemen is divided between Sunnis and Shiites. Some figures indicate that 35 percent of the population follow Shia Islam, between Zaydis, which are the majority, Ismailis and Twelvers. (7) This is where the Houthis are revealed as one of the most important Shiite factions in the Yemeni society.

Saudi Arabia has been increasingly concerned that the Houthis are a Yemeni group close to Iran and influenced by the political literature of the Islamic Republic, especially as the Houthi movement has been politically and religiously coincides with Iranian revolutionism in its approaches and slogans. This is indicated by the adoption of a doctrine of confronting global arrogance, and opposition towards Israel and support for the Palestinian armed resistance.

In fact, the group’s main slogan is, “God is the greatest. Death to America. Death to Israel. Curse on the Jews. Victory to Islam.” (8)

With this slogan and these leanings, the Houthis formed increasingly worrying dynamics for Saudi Arabia in the ideological-religious dimension, which caused Riyadh to view them as a tool for Tehran, one that tries to propagate Iran’s influence in Yemen near Saudi borders.

Saudi Arabia’s reaction to developments in the Yemeni crisis

Considering that the Saudi kingdom is one of the most important regional players vis-à-vis Yemen, it was necessary for it to devise a precise plan to counter what is happening in the country by defining clear goals and effective mechanisms. Based on this approach and to achieve its goals, Saudi Arabia’s reaction to the crisis in Yemen was based on the points below:

- Any change in Yemen, regardless of its appearance or details, would have direct and indirect repercussions for Saudi Arabia and its national security.

- It is important to contain tensions and their repercussions to within Yemeni borders and prevent them from reaching Saudi territory or borders.

- Any change in Yemen must not lead to the formation of a new political regime that would be against Saudi Arabia and its policies, which was the case in Iraq following the US invasion.

- The Houthis must not have any significant role in a new Yemen after Ali Abdullah Saleh’s regime because then, Saudi Arabia believes, they would form group like Hezbollah.

- There must be no hesitation in directly confronting any Iranian action aiming to expand Tehran’s influence in Yemen because it would be a direct security threat to Saudi Arabia. (9)

To achieve these goals, Saudi Arabia adopted a gradual policy concerning developments in Yemen over four stages:

- Containment

- Controlled change within the framework of Saudi national security considerations

- Direct military intervention

- Proxy war (10)

Just days after Zine El Abidine Ben Ali, Tunisia’s then-president, lost power and fled to Saudi Arabia on 14 January 2011, protests began in Yemen on 17 January, calling for the ouster of Ali Abdullah Saleh. The containment stage adopted by Riyadh was a serious challenge to Saudi decision-makers due to the demographic, social and political diversity of protesters. Moreover, there was no clear leadership capable of controlling the revolutionaries, their wide-ranging political leanings, their different tribal and clannish affiliations, and civil society institutions as a whole. On the other hand, the ceiling for what the Yemenis demanded was higher than the ceiling Riyadh was moving under during its containment stage, as the people called for fundamental changes while Riyadh wished to maintain the overall political structure of the government and engage in reforms that would satisfy the Yemenis and the revolution.

Saudi Arabia’s policy of containment in aims of pacifying what was happening in Yemen and lead to a desirable path was unsuccessful. Tehran concluded that Yemen was on the precipice of important changes and Riyadh faced serious challenges in playing the role of patron for a solution. (11) Therefore, Iran decided that its approach needs to consist of watching closely and preparing for a stage in which events in Yemen would spin out of control.

After these developments, Saudi Arabia came up with a new initiative to move toward the second stage. Saleh was removed from power in Yemen and replaced with Abd-Rabbuh Mansour Hadi. As the protests continued, the new president faced hefty challenges in his effort to control the situation in Yemen. A variety of factors came together to form what a large part of the Yemeni people considers the failure of Hadi’s policies to practically answer the demands and slogans of the revolution, the most important of which include:

- The failure of the political establishment led by Mansour Hadi to distribute power in a way that would be proportionate to the goals, aspirations and demands of the revolutionaries in Yemen.

- The dependence of Mansour Hadi’s policies on Riyadh, and the link between the legitimacy of the new political establishment in Yemen to external factors.

- The Houthis’ clear opposition to Mansur Hadi’s policies and considering them cruel policies that undermined and weakened their rights in Yemen. (12)

All these factors led to a new wave of protests and demonstrations, coupled with an armed movement against the government of Mansour Hadi led by the Houthis, who were supported by forces from the Yemeni army and others close to former President Saleh. This ended with the Houthis and their allies moving taking over Sanaa using arms, and surrounding the president and his officials inside the presidential palace. Mansour Hadi tried to contain the situation by submitting his resignation to the parliament, which refused it. The Houthis did not back down, believing that the president was trying to buy time. Owing to the president and his administration’s complete inability to stand against the armed Houthi offensive, the protests and other internal developments, Mansour Hadi and his government left Sanaa and officially requested Saudi Arabia to intervene militarily against the Houthis. (13)

These events marked a violent end to the second stage of Saudi Arabia’s reaction to the crisis in Yemen, as a result of which Riyadh accused Tehran of encouraging the Houthis and supporting them in their takeover of Sanaa and toppling of the Mansur Hadi administration. Tehran said the Houthis’ move in Sanaa and forceful offensive was unexpected.

In March 2015, Saudi Arabia decided to declare war against the Houthis and their allies in Yemen, thereby initiating the third stage. Code-named “Decisive Storm”, the military operation of the Saudi-led coalition began with these steps:

- A complete air, sea and ground blockade, and declaring Yemen a closed military operations zone

- Declaring Saudi Arabia’s full control over Yemeni airspace and threatening to target any violators of the airspace.

- Intense aerial bombardment against the Yemeni air defenses, military communication systems, and military airports

- Directing a part of the aerial strikes on military facilities operated by the Houthis and their allies

- Direct warnings to Iran that if it violates the sea or air blockade by sending aircrafts or vessels, they would be targeted and destroyed (14)

In April 2015, Saudi Arabia declared Operation Decisive Storm over after achieving its goal of neutralising all forms of threat that could pose a danger to it or other Gulf countries from Yemeni soil. At the same time, Saudi Arabia announced the war’s second stage, a new military operation code-named “Restoring Hope” with these objectives:

- Reconfiguring the political process in Yemen based on UNSC Resolution 2216, the GCC initiative, and the results of the National Dialogue Conference in Yemen

- Supporting the people of Yemen and protecting them from the Houthis and their policies

- Maintaining the air, sea and ground blockade and creating a mechanism to search ships and aircraft with the aim of preventing the arming of the Houthis

- Designating the Houthis a terrorist group allied with Iran and maintaining the military campaign against them

- Evacuating foreign nationals

- Facilitating the arrival of international humanitarian aid to the Yemenis

The military operation ended with the Houthis agreeing to return to the negotiating table, but failed to drive them away from Sanaa and restore the legitimacy of Mansour Hadi and his administration. However, it succeeded in restoring five governorates in southern Yemen: Aden, Abyan, Lahij, Shabwah, and Ad-Dali’. These areas played a significant role in the next stage, when Yemen witnessed period of proxy war between Saudi Arabia and Iran.

After that, events in Yemen gradually took a course in which all negotiation tables failed to reach a sustainable ceasefire that would allow for a Yemeni-Yemeni dialogue leading to a political solution. This led to military confrontation that materialised as a proxy war between the Iran-backed Houthi movement and government forces backed by Saudi Arabia.

Yemen’s position in Iran’s foreign policy

After the Islamic revolution in Iran, North Yemen was one of the first countries that allied itself with the Islamic Republic by sending an official delegation consisting of 15 political and religious figures. In the same year, its ambassador in Tehran met with Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, the founder of the Islamic Republic, and gifted him a copy of the Qur’an from President Ali Abdullah Saleh.

It was clear that North Yemen was ready to develop relations with Iran following the revolution, but its ties with Arab states, especially those of the Gulf region, led Sanaa to adopt a conservative approach toward Tehran. The scene changed drastically following the start of the Iran-Iraq War, when North Yemen stood, alongside other Arab powers, by Iraq against Iran, whereas South Yemen was closer to Iran’s position during the eight-year war.

In 1990, the northern and southern parts of Yemen were unified. But after the Iran-Iraq War ended and a new, unified Yemen emerged, not much change happened in the nature of Yemen’s relations with Iran. This was due to a number of convictions on the Iranian side, which included:

- In Iran’s point of view, Yemeni policies and approaches at the time were an extension of the policies of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) led by Saudi Arabia.

- After unification, Yemen maintained the position of its northern parts towards Iran as an essential part of its official position.

- Iran was distrustful toward Ali Abdullah Saleh, who had become president after unification in Yemen. (16)

After the situation in Iran stabilised following the war with Iraq, Tehran began to reconsider its assessment of the importance of Yemen based on two factors:

- An ideological factor that was created as a result of the revolution and was based on giving attention to the condition of Shia minorities all over the world

- A strategic factor in political geography, considering that the Bab al-Mandab Strait is a vital part of Yemen’s national security. (17)

Therefore, it is clear that Yemen’s position in the foreign policies of Iran and Saudi Arabia is dependent on the same ideological and geopolitical factors, but those factors run counter to each other in practical and real-world policies.

Iran’s reaction to developments in Yemen’s crisis

The major developments that happened following the US invasion of Iraq in 2003 are the main reason behind the fast-rising trend of competition between Tehran and Riyadh. By 2006, this competition turned into a geopolitical alignment in the Middle East, whereby the discourse in Saudi Arabia was dominated by the Shia crescent being branded a dangerous Iranian project, and the discourse in Iran consisted of branding a sectarian-takfiri approach led by Saudi Arabia as a counter to Iranian influence in the region.

This change in the discourse in Riyadh and Tehran transformed tensions from competition based on historical contrast in identity and ideology to violent clashes in geopolitical areas. This became very evident in Yemen after 2011, as it became the most obvious arena in which red lines were crossed between the two countries outside of the framework of their traditional historical competition. (18)

Iran’s strategic evaluation of developments in Yemen was based on a variety of factors that overlap with Tehran’s view on the Arab revolutions and their position in Iran’s sphere of influence, including:

- The revolution in Yemen is a popular revolution against an authoritarian regime that is backed by the West.

- The revolution was partly against the policies of President Saleh as an ally of Saudi Arabia and Western powers.

- The revolution in Yemen was an extension of the revolutions in Egypt, Libya and Tunisia, and its victory would lead to a decline in the influence of the US-led West.

- Yemen is a fundamental part of Saudi Arabia’s national security and a revolution in Yemen would constitute a direct threat to Saudi Arabia and its political regime. (19)

These factors formed the grounds for Iran’s response to the crisis in Yemen based on two principles: first, that change was inevitable in Yemen; and second, that Saudi Arabia would be unable to contain or guide the crisis in a way that would fully address its security concerns. With this approach, there were four levels to Iran’s response:

Politics

Tehran preferred to express its stance on the crisis in Yemen within the framework of a political solution; so, it supported the concept of a political solution with three dimensions:

- The intrinsic dimension: the proposal of a plan by Iran consisting of clear points and a gradual solution that would lead to Yemeni-Yemeni talks and create a new political establishment that all Yemeni people would accept.

- The regional dimension: supporting all Yemeni talks that convene under regional auspices

- The international dimension: supporting the plans of international envoys for the crisis in Yemen. (20)

Security and military

The security and military level specifies the provision of different kinds of support to the Houthis on all levels to guarantee that military and security developments would lead to the exclusion of the Houthis from the Yemeni equation. (21)

Ideology

The ideological level is based on using all options that would make the Houthis a real and practical ally rather than a mere supporter of the Islamic Republic, and reinforcing all of the historical, religious and political grounds that facilitate this. (22)

Geopolitics

The geopolitical level entails intensifying military and logistical presence in international waters close to the Bab al-Mandab Strait and emphasising that the strait is not controlled by Saudi Arabia’s policies. (23)

These factors played varying roles depending on the nature of the stage in a long path where Tehran was keen to fortify the political situation with field achievements, in addition to supporting the ideological element of the constraints of political geography. Thus, events developed in a way that put the Houthis at the heart of the Yemeni equation, a difficult situation that cannot be overcome, contributing to the transformation of Yemen into an arena for the proxy war between Saudi Arabia and Iran.

Cold war in Yemen: Conceptual and field evidence

The strategic assessment of both the Kingdom and the Islamic Republic was firm about completely ruling out the idea of direct war between the two countries, whether in Yemen or in other areas of regional conflict. This is limited the confrontation to two levels. The first took the form of a cold war between Tehran and Riyadh, by harnessing and employing all the elements of latent power, which was practically embodied in the consolidation of the concepts of proxy wars between the two parties through local Yemeni allies who strategically revolve within the orbit of the regional ally. The second was a direct Saudi war against some of the special sources of power of the Houthi group, which cannot be neutralised by the local ally in a way that guarantees desired results in advance. (24)

Consequently, Saudi Arabia regarded Iran’s movements in Yemen a threat to its national security given Tehran’s efforts to change the balance of power in Yemen through its Houthi allies. Riyadh also considers that the Islamic Republic is practicing “dangerous terrorism” when it applies pressure to raise the level of threat against Saudi Arabia from Yemeni territory. Iran, on the other hand, believes that Saudi Arabia wants a Yemen that is completely attuned to Saudi policies and without any influential role for the Shia component, and is trying to achieve this by feeding sectarian and religious confrontations through a senseless war with no clear future. (25)

The allies of Yemenis adopted the logic of regional powers in the ongoing conflict on the ground, which has created a complex situation in Yemen, making the crisis take on regional dimensions that surpass its internal Yemeni dimensions in importance. This was revealed by the inability of local Yemeni actors to reach any real understanding without the cover and support of a regional ally.

Saudi Arabia’s manoeuvres in Yemen at the height of the proxy war was based on effective field factors and developments rather than political realities, the most important of which being:

- Iran sought to increase its influence in the immediate area of Saudi Arabia’s national security using its Houthi allies.

- Tehran wanted to add a fourth branch to its “axis of resistance”, which forms the basis of its regional influence, by backing the Houthis with arms, missile technology and drones.

- Contrary to what the Islamic Republic states publicly, it tried to convert its struggle with Saudi Arabia from competition to a direct confrontation by proxy by offering military support and non-traditional armament to its Houthi allies.

- The Houthi movement in Yemen represents Iran’s force in targeting security and stability along Saudi borders.

- Houthi control of Yemen or influence in future strategic decision-making in the country would entail negative repercussions for Saudi Arabia. (26)

Accordingly, Riyadh came to the conclusion that if Iran succeeds in Yemen through its Houthi ally, it will have made a significant achievement and created new influence for itself in the Middle East from the borders of Israel, passing through Lebanon, Syria and Iraq, to the borders of Saudi Arabia. This would then mean Iran’s strategic victory in the region.

To counter the factors that Saudi Arabia used as leverage for presence in all aspects of the cold war in Yemen, Iran devised a reverse approach with contradicting factors. Tehran identified Saudi Arabia’s role in Yemen as reckless, aggressive and exclusionary based on:

- Saudi Arabia’s relentless efforts to eliminate the Shiite component from the equation even if through direct war

- Riyadh’s treatment of the Houthis as a foreign enemy of Saudi Arabia with the aim of supressing opposition inside Saudi Arabia

- Saudi Arabia’s designation of the Houthis as a regional threat followers of Iran

- Sectarian and religious mobilisation as a tool for the establishment of Arab and Islamic coalitions on the basis that a Sunni Saudi Arabia would counter a Shiite Iran that wants to control the Arabs and their capitals (27)

With the Yemeni crisis shifting to the regional sphere, given that it leads the dynamics of events in Yemen, and the cold war between the two regional powers reaching its peak, Riyadh and Tehran began exchanging blows in dangerous areas outside of Yemeni territory. The targeting of civilian and military airports and a number of sensitive centres in Saudi cities with ballistic missiles and drones by the Houthis had a huge impact on the development of Saudi discourse on Iran. Riyadh increased its threats, and Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman announced that he would take the fight to Tehran.

Tehran, on the other hand, officially accused the United States, Israel and the intelligence services of a number of states in the region, including Saudi Arabia, of supporting two bloody attacks on Iranian soil. The first came in the form of a dual and simultaneous attack in July 2017 carried out by elements who presented themselves as members of the Islamic State, targeting the Iranian Parliament building and the Mausoleum of Ayatollah Khomeini in Tehran., killing 12 people. (28) The second attack was an armed assault on a military parade in Ahvaz in 2018 that left 25 Iranian civilians and military personnel dead. An armed Iranian opposition group that calls itself the National Liberation Movement of Ahvaz accepted responsibility for that attack. (29)

In September 2019, a year after the second attack, the Houthi group announced its bombing of Saudi Aramco’s oil facilities with ballistic missiles and drones in addition to direct and successive strikes targeting vital centres within Saudi territory. Decision-makers in Riyadh were convinced that an attack of such magnitude could not have been carried out without a green light to the Houthis from Iran. Moreover, they believed that Tehran had facilitated the attack logistically by providing the equipment used in an attack that was considered a total violation. (30)

The fact that tensions between Iran and Saudi Arabia had reached such a high level sounded alarms at multiple levels. It became necessary to de-escalate, freeze tensions and make room for the possibility of conflict resolution. Domestically, in both countries, prominent voices called for calm and the opening of pathways for dialogue and understanding. Regionally, countries that perceived the danger of the Saudi-Iranian confrontation spiralling out of control played the role of mediation in an attempt to achieve a breakthrough in the severed relations between the two countries, allowing them to have direct bilateral meetings. Internationally, there were indications that the proxy conflict between Tehran and Riyadh could escalate to direct confrontation, which threatens both regional and international security.

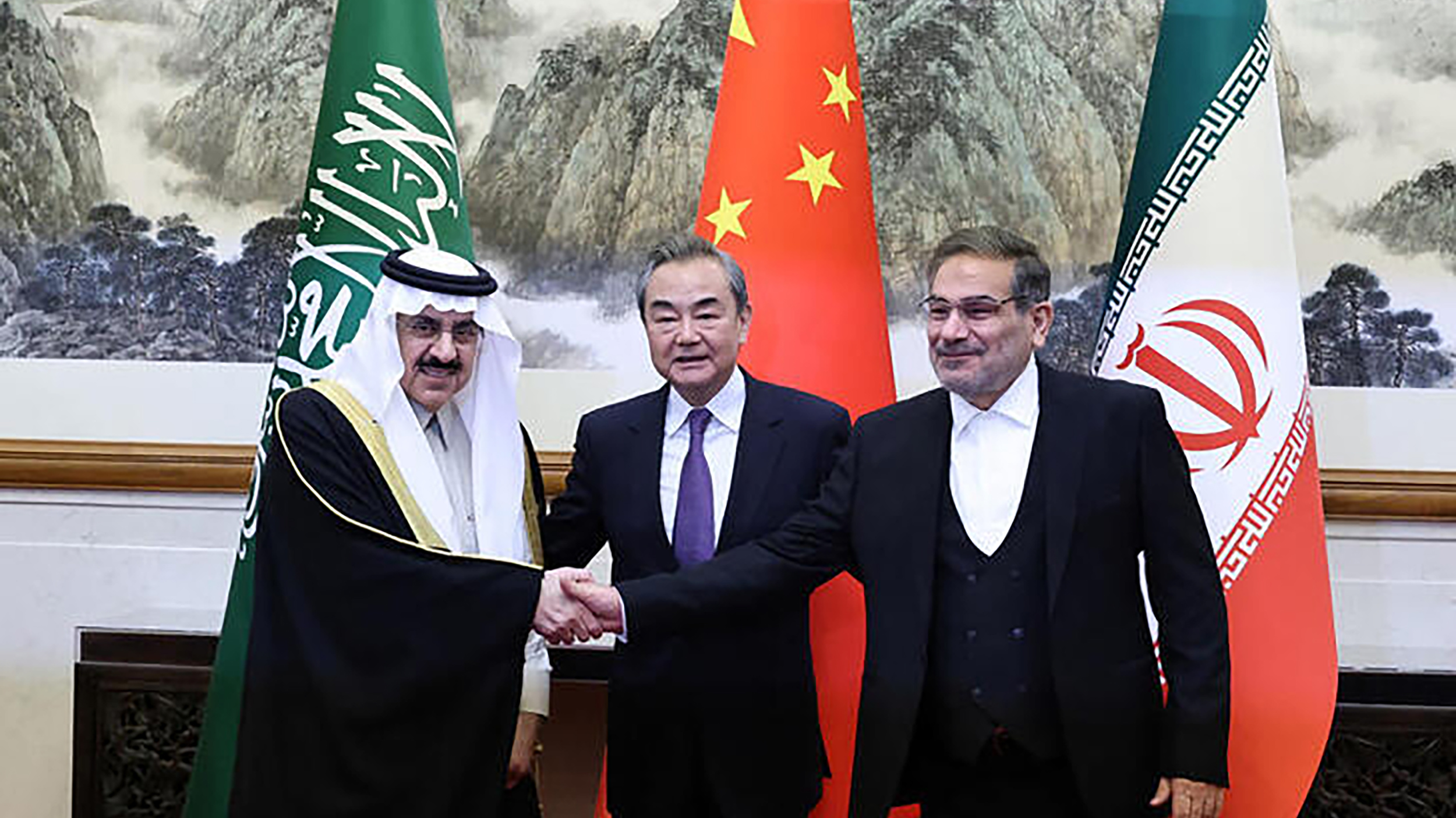

These efforts, through meetings between security officials in Oman, led to dialogue between Iran and Saudi Arabia over the course of five rounds of direct talks in Baghdad, culminating in an agreement signed between Iran and Saudi Arabia in Beijing with the aim of restoring diplomatic relations.

The “agreement” between Saudi Arabia and Iran: The accuracy of the term and scenarios for success and failure

What makes the Saudi-Iranian agreement signed in the Chinese capital on 10 March 2023, more complex is the ambiguity surrounding the agreement, whether in its formal nature or the secrecy of its content. The term "agreement" seems vague here; and the fact that its key provisions remain confidential does not allow what happened to be subject to analytical or inferential logic. Is it a preliminary agreement and a roadmap to the resolution of differences and dispute, or an integrated agreement with bilateral and regional dimensions? Does it, regardless of its name, deal with the points of regional contention between the two powers? Can we rely on the restoration of bilateral relations after a seven-year diplomatic rift to ease tensions regionally, or will it have the opposite effect? Are there real guarantees for the implementation of what has been agreed upon? And what are the factors that determine the success or failure of the agreement's implementation?

To answer these questions, the first step is to dissect what happened between Iran and Saudi Arabia in Beijing in order to label it accurately. This requires placing the term “agreement” in the context of different scenarios possibilities to define the rapid rapprochement between Tehran and Riyadh:

- A comprehensive deal at various levels that is implemented gradually, necessitating that the transition from one level to another requires a full and successful implementation of all the provisions in the previous level. If this is what has been signed in China, it is a major deal between two regional powers that are in pursuit of peace. This in itself shows that regional dossiers will be an inseparable part of the agreement and play a role in its significance and seriousness.

- A potential agreement based on the immediate end of all forms of confrontation, the reduction of tensions, abstaining from provocative remarks and focusing on mutual interests in aims of build an accumulative state of understanding that addresses all files. This would enable Saudi and Iranian decision-makers to make well-considered regional decisions.

- An agreement borne out of necessity as a response to external factors that are out of the hands of either party, such as the regional and international ramifications of Russia’s war on Ukraine. In this scenario, an agreement would be more like the decision to transition from a brutal pre-emptive war to a cautious tepid peace through mutual concessions, the recognition of each party’s regional stature, and the management of the conflict based on mutual interests without making substantial and painful concessions regarding regional competition.

- A crucial agreement based on the rationale that peaceful coexistence and crisis management would be less costly than increasing mutual tensions.

Regardless of the nature and contents of the agreement, strategic necessities compel both states to focus on difficult issues and strive to achieve practical progress before entering another phase of competition. For Saudi Arabia, Yemen would be a fundamental condition in any significant agreement with Iran, whether it is based on necessity or a major deal. Thus, Saudi Arabia appears to be concerned with two key points:

- Security guarantees from Iran, especially regarding Yemen, which is where the importance of what has been disclosed about agreement lies, as it shows the agreement contains a clause on implementing the security agreement the two sides signed in 2001

- Ensuring Iran’s capability and seriousness in pressuring the Houthis in Yemen to try to find a political solution that coincides with the interests of Saudi Arabia

For Iran, strategic necessity calls for the focus on:

- Economic benefits, which explain why Riyadh’s official statement the possibility of Saudi investments flowing rapidly into the Iranian economy

- Riyadh abandoning its classification of Iranian influence as support for terrorism and ending its support for Iranian opposition, especially those that adopt armed military action against the regime in Iran

- Dealing with Iran’s influence in Yemen as part of the solution rather than the root of the problem

Factors of the agreement’s success

- Beijing's sponsorship of the agreement and keenness to implement it as a first test for China as an international player in the Middle East, which is considered an arena for American influence

- China's possession of strong pressure tools on both Iran and Saudi Arabia, such that disavowing the implementation of the agreement becomes costly in the scope of the relationship with Beijing

- Saudi Arabia’s dire need to end the war in Yemen and the view that this is not possible without Iran

- Iran’s dire need to defuse the conflict with Saudi Arabia amidst domestic challenges due to popular protests and critical economic conditions

- The absence of an American veto on the agreement between Iran and Saudi Arabia

- Arab and Islamic backing for the announced agreement between Riyadh and Tehran

- The world after the Russian-Ukrainian war, the rapid changes on the international stage, and the possibility of the global situation spiralling towards non-traditional confrontations that produce new alignments

- Saudi Arabia and Iran’s prioritisation of regional stability, given increasing Israeli threats of a military strike on the Iranian nuclear program

Factors of the agreement's failure

- The clear lack of trust between Iran and Saudi Arabia

- The historical relationship between the two countries is marked by competition and tension, even if there were periods of understanding and cautious agreement.

- The organic overlap between such an agreement and the regional dimension of other dossiers in which Saudi Arabia does not appear to be involved, such as the fate of the nuclear deal between major powers and Iran

- Riyadh and Tehran’s inability to exert pressure on their allies in the region to cooperate and accept the outcomes of the agreement sponsored by China

- The Israeli response to the progress of the Iranian nuclear program, which may push it to use the military option against Tehran; and this could lead to a broad confrontation in the region.

- The lack of an internal consensus that reconciliation and understanding are the decision of the ruling regime, and not a certain faction within it

Summary

Differences between Saudi Arabia and Iran in the formation of historical identity have always formed a ground that fuels conflicts based on religious and ethnic ideology in the areas of influence in West Asia. However, these differences did not prevent cooperation between Saudi Arabia and Iran as allies and strategic partners of Washington during the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union.

After the victory of the revolution in Iran in 1979 and the establishment of the Islamic Republic, all forms of cooperation and understanding between Tehran and Riyadh collapsed and competition increased and expanded. This was spurred by the policy of exporting the Islamic Revolution from Iran to its region and Saudi Arabia's full support for Iraq during its eight-year war with Iran.

In 2003, the balance of power and threat between the Kingdom and the Islamic Republic was greatly disrupted due to the US invasion of Iraq, the overthrow of President Saddam Hussein's regime, and the emergence of a new political system led by the opposing Shia class, which had been close to Iran for many years. This was the main reason behind the shift of the conflict between Tehran and Riyadh, as two regional powers, to a confrontation across the Middle East.

Afterwards, the Arab Spring revolutions that started in Tunisia in 2011 constituted the key catalyst in breaking the rules of regional conflict, especially when the wave of revolution reached both Syria and Yemen, considering they are the two countries’ direct spheres of influence. However, Yemen was where the two regional powers tested their own abilities to impact each other’s spheres of influence.

Riyadh viewed the events in Yemen as a serious threat to its national security, political establishment and strategic equations, while Tehran considered it a new factor in its regional competition with Saudi Arabia. This clash of visions led to a fierce cold war on Yemeni soil, in which both Saudi Arabia and Iran crossed a critical red line that governed the nature of their conflict in previous stages.

From Saudi Arabia's perspective, the rise of the Houthis as an armed group capable of influencing political decision-making in Yemen was a real nightmare. This is what led Saudi Arabia to declare war on Houthi-controlled areas in Yemen with the aim of retaking the capital, Sanaa, from the group and eradicating Iranian influence in the country. This was met with escalation by the Iran-backed Houthis, through the targeting of oil facilities and sensitive centres in Saudi Arabia with missiles and drones.

Thus, Yemen found itself caught in between two regional powers engaged in bone-breaking battles on its soil whether through the direct Saudi war on the Houthis or proxy wars by local Yemeni allies of Saudi Arabia and Iran. The war started by Saudi Arabia did not result in clear outcomes like debilitating the Houthis or pushing them to accept Riyadh’s conditions for a political solution; and the Houthis failed to control Yemeni territories, especially southern cities. This ultimately led to a Yemeni-Yemeni war that was a front for a cold war between the regional actors.

As time passed, decision-makers on both sides were convinced that it was necessary to test each other's intentions about resolving the conflict in Yemen through a bilateral dialogue table. This entailed five rounds of dialogue in Baghdad and meetings in Oman. Eventually, all the mediations and negotiations resulted in the signing of a joint agreement in the Chinese capital, Beijing, aimed at restoring diplomatic relations between Tehran and Riyadh after a seven year rift.

The agreement between Riyadh and Tehran has been subject to much analysis and evaluation. But the relative consensus is that any Saudi-Iranian rapprochement, regardless of its nature and content, will find itself obligated to resolving the Yemeni crisis, which is an important factor in the success of this rapprochement, whether it is an agreement between two parties in distress or a major regional deal.

- Mohammad-Reza Hafeznia, Khalij-e Fars va Naghsh-e Estratezhik-e Tangeh-ye Hormoz [The Persian Gulf and the Strategic Role of the Strait of Hormuz] (Tehran: Samt Press, 2003), pp. 41-60.

- Ibid., pp. 93-105.

- Reza Simbar and Milad Pahlavan Mangoudehi, “Jang-e Sard-e Mantaqei-ye Iran va Arabestan dar Bahran-e Yemen (2011-2020) [The Cold War between Iran and Saudi Arabia in the Yemen Crisis (2011-2020)]”, Siasat va Ravabet-e Bayn al-Mamalik, Vol. 5, Issue 9, p. 65

- Ibid., p. 68.

- Dina Esfandiary and Ariane Tabatabai, “Yemen: An Opportunity for Iran-Saudi Dialogue”, The Washington Quarterly, 2016, pp. 155-174.

- Seyyed Shamseddin Sadeghi and Kameran Lotfi, “Bahran-e Yemen: Jadāl-e Zheopolitiki-ye Mahvar-e Mahafazat-kari bā Mahvar-e Moqavemat-e Eslami [The Crisis in Yemen: The Geopolitical Battle between the Conservative Axis and the Axis of Islamic Resistance]”, Elmi Pazhuheshi-ye Siyasi-ye Jahani, Vol. 5, Issue 1, 2016, pp. 41-69.

- “Shia dar Yemen [Shias in Yemen]”, Theological Research Center, https://bit.ly/3VGwjp4 (accessed 2 April 2023).

- “As-sarkha tushakkel khataran balighan ‘ala al-yahud wa al-nasara wa heya aqal ma yumkin bihi muwajahatihim [The shout constitutes serious danger to Jews and Christians, and it is the least that they can be confronted with]”, Ansarollah, 3 June 2021, https://bit.ly/3VWtFMl (accessed 8 May 2023).

- Mehran Kamrava, “Hierarchy and Instability in the Middle East Regional Order”, International Studies Journal, Vol. 14, Issue 4, May 2018, pp. 1-35.

- Nahid Hosseini Moghadam and Bahram Yousefi, “Rahbord-e Arabestan-e Saudi dar Ghabl-e Behran-e Yemen [Saudi Arabia's strategy towards the Yemeni crisis]”, Bein-al-Mellali Pezhvahesh Mellal, Vol. 3, Issue 25, 2017, pp. 79-103.

- Seyyed Amir Niakouei and Ehsan Ejazi, “Vakavie Behran-e Amniati dar Yemen: Alal va Zamin-ha [Analysing the Security Crisis in Yemen: Causes and Backgrounds]”, Tahghighat-e Siyasi-e Bein-al-Mellali, Issue 28, 2016, pp. 49-50.

- Ibid., pp. 51-60.

- Moghadam and Yousefi, p. 81.

- Enea Gjoza and Benjamin H. Friedman, “End U.S. Military Support for the Saudi-Led War in Yemen”, Defense Priorities, 4 January 2019, https://bit.ly/3MdvIbN (accessed 2 April 2023).

- Ibid.

- Seyyed Ali Nejat et al., “Rahbord-e Arabestan-e Saudi va Jomhuri-ye Eslami-ye Iran dar Ghobal-e Bahran-e Yemen [Saudi Arabia and the Islamic Republic of Iran's Strategy towards the Yemeni Crisis]”, Motale'at-e Ravabet-e Beinolmelal, Vol. 9, Issue 33, 2016, pp. 137-139.

- Ibid., pp. 180-183.

- Seyyed Shamseddin Sadeghi and Kameran Lotfi, “Bahran-e Yemen: Jadāl-e Zheopolitiki-ye Mahvar-e Mahafazat-kari bā Mahvar-e Moqavemat-e Eslami [The Crisis in Yemen: The Geopolitical Battle between the Conservative Axis and the Axis of Islamic Resistance]”, Elmi Pajuheshi-ye Siyasi-ye Jahani, Vol. 5, Issue 1, 2016, pp. 41-69.

- “Nashast-e barresi-ye tahavolat-e Yemen bergozar shod [A session was held to review the developments in Yemen]”, Iranian World Studies Association, https://bit.ly/3U12Rt0 (accessed 2 April 2023).

- Mohammad Reza Dehshiri and Fereshteh Maboudi, “Arzyabi-e Rahbarde Jomhouri-e Eslami-e Iran dar Ghobale-ye Bahran-e Yemen [Evaluation of the Islamic Republic of Iran's Strategy towards the Yemen Crisis]”, Siyasat-haye Rahbordi va Kalan, Issue 19, 2016, p. 153.

- Ibid., p. 154.

- Ibid., pp. 154-155.

- Azadeh Babaeinejad, “Bab al-Mandab: Zaroori baraye Iran ya Arabestan [Bab al-Mandab: Necessary for Iran or Saudi Arabia?]”, Shargh, 2 August 2018, https://bit.ly/3pdQgaJ (accessed 2 April 2023).

- Hamid Reza Shirzad Nashli et al., “Tahlie Ravaabet Iran va Arabestan dar Mantagheye Gharb-e Asia [Analysis of Iran and Saudi Arabia's Relations in West Asia: Yemen as A Case Study]”, Alum-e Siyasi, Issue 52, 2021, pp. 10-16.

- Alireza Samii Esfahani et al., “Jiopolitik-e Hoviat va Ta'sir-e An bar Rahbord-e Amniati-ye Iran va Arabestan dar Bahran-e Yemen [The Geopolitics of Identity and its Impact on the Security Strategy of Iran and Saudi Arabia in the Yemen Crisis]”, Pajoohesh-haaye Siasi-ye Jahane Eslam, Issue 2, 2015, pp. 17-20.

- Reza Eltyaminia et al., “Bahran-e Yemen: Zaminha va Ahdaf-e Modakhelat-e Khareji-ye Arabestan va Āmerika [The Crisis in Yemen: The Background and Objectives of Foreign Interventions of Saudi Arabia and the United States]”, Pajouhesh-haaye Rahbari-ye Siasi, Issue 18, 2015, pp. 187-189.

- Ruhollah Teymouri et al., “Taghabol-e Siyasat-e Khareji-ye Iran va Arabestan dar Bahran-e Yemen ba Ravesh-e Sazeh-angarane [The Confrontation of the Foreign Policies of Iran and Saudi Arabia in the Yemen Crisis through a Structuralist Approach]”, Motaaleate Bidari-ye Eslami, Issue 10, 2015, pp. 82-98, https://bit.ly/3HOI1YW (accessed 8 May 2023).

- “Qalibaf dar natagh-e pish az dastur: Emrooz sabt shode ke pas-e hamlah-ye Daesh be Majles-e Servis-haye Ettela'ati Amrika, Esra'il va bar-khey-e keshvar-haye mantaghe budand [Qalibaf: Today, it has been proven that the intelligence services of America, Israel and some countries in the region were behind the ISIS attack on the parliament]”, Iranian Labour News Agency, 7 June 2020, https://bit.ly/40xJ1YR (accessed 29 March 2023).

- “Marvari bar hadiseh-ye terroristicheh-ye raje khunin-e 31 shahrivar-e 97 Ahvaz [A review of the terrorist incident of the bloody parade on 22 September 2018, in Ahvaz]”, IRNA, 22 September 2018, https://bit.ly/3pm7eUg (accessed 29 March 2023).

- “As-Saʻudiyyah taqul: Daʻm ʼIran lil hujum ʻala Aramco "la yumkin dahdhuh" wa taʻredh asliḥa [Saudi Arabia says Iran’s support for the attack on Aramco “cannot be ignored”, and displays arms]”, Reuters, 18 September 2019, https://reut.rs/3LFKXs5 (accessed 8 May 2023).