The bombs are falling and the number of graves is rising in Ukraine, while inhumanities are breaking out. On 24 February 2022, Vladimir Putin decided to bring the high intensity war up-to-date by invading Ukraine, under the cover of a “special military operation” and “denazification,” a dialectic far from reality that gathers all the characteristics of a war: a collective and organised armed violence, as Clausewitz described it. (1)

The beginning: The first signs in history

War is a race towards power. In the case of Russia, it is a will to recover a lost power. Historically, Ukraine, Russia and Belarus were all founded by the so-called “Rus of Kiev” during the 9th century, before the territory was divided. A large part of what we consider Ukraine today was invaded by Russia in 1654 thanks to the Treaty of Pereïaslav. The Russification of the territory was intensified during the 18th century, when many Russians settled in the area and Russia decided to limit the use of the Ukrainian language and forbid it in schools in 1874. This led to the renewal of an autonomist movement and a struggle for independence. Ukraine finally recovered its sovereignty for a few years, before it was fully integrated into the Soviet Union. Mass deportations and an organised starvation, which reduced the Ukrainian population by more than 5 million inhabitants in the 1930s, provoked the comeback of the independence movement. The Soviet Union had to fight until 1956 for the definitive annihilation of anti-communist partisan groups.

In 1954, Nikita Khrushchev – who is of Ukrainian origin himself – attached Crimea to Ukraine. Ukraine therefore has an inseparable history with Russia, then known as the cradle of Russian civilisation and which participated in the foundation of Orthodoxy. Nonetheless, the Ukrainian population is accustomed to occupation, and a centuries-long history of guerrilla and resistance is part of its national spirit.

As the USSR lost its superpower status with the end of the Cold war, Ukraine declared its independence first, initiating the dislocation of the Soviet empire. That decision was confirmed by a referendum on 1 December 1991 in which 90% of voters said “yes” to Ukrainian independence, Crimea included.

This decision was sealed by various agreements, such as the Budapest Memorandum in 1994 which guaranteed the territorial integrity of Ukraine, the Russian-Ukrainian friendship treaty in 1997 or the agreements relating to the base of Sevastopol in 1997 and 2010. After the Russian-Georgian conflict in 2008, Putin also stated in an interview that Moscow "long ago recognised the borders of today's Ukraine," and added that Crimea is not a "disputed territory."

But without Ukraine, Russia is only a “diminished power,” according to Zbigniew Brzezinski. (2) This is a vision shared by many Russians, fuelling nostalgia of a glorious past that Vladimir Putin has been working to restore for more than 20 years in every way – economically, diplomatically, technologically, geopolitically and so on. The 2014 illegal annexation of Crimea was only the first step of his political project; we are now living the second one.

A three-day war

For months, Russia gathered troops all around Ukraine. On 21 February 2022, Putin recognised the independence of the pro-Russian autonomous regions of Donetsk and Lugansk in the Donbass, which had already been at war with Ukraine since 2014 thanks to Russian military support. Russian tanks and military assets kept moving all along the Ukrainian border, including in Belarus.

Three days later, at 5:30 am, Putin officially announced the beginning of a “special military peace operation” under the aegis of denazification and demilitarisation of Ukrainian territory, with an official target of a regime change in Kiev. Only a few minutes after Moscow's announcement, bombs fell in the Donbass as well as Kiev, Kharkiv and Odessa. At 7:00 am, Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy decreed martial law and refused the evacuation offers of the United States: the war had begun. This “operation” is completely illegal since Russia acted without any mandate from the United Nations, but the violations of the international law do not stop there: although the Russian army claims not to target civilians, images show Sukhoi fighter jets bombing civilian residences from the very first hours of the invasion.

Very quickly, we learned that Russian ambitions were much greater than the ones officially announced. An article written a few days before the beginning of the war began was inadvertently broadcast on Ria Novosti and Sputnik, two official Russian channels. This article states that Russia is restoring its historical plenitude by reuniting the Russian world in its entirety with Great Russia (Russia), White Russia (Belarus) and Little Russia (Ukraine), referring to the national humiliation that this separation causes. (3) It claims that “Ukraine has returned to Russia,” what they call its “natural state,” even though the first Russian boot had just crossed the Ukrainian border. Moreover, it says that Russia, Belarus and Ukraine will from now on act geopolitically as a whole. “Did anyone in the old European capitals, in Paris and Berlin, seriously believe that Moscow would give up Kiev?” asks the author. Putin's real project was to take over Ukraine in its entirety and without concessions, with the reunification of the so-called “Russian peoples” as his leitmotif. Putin thought that this fight was won in advance, that his army would be most welcomed and that the Ukrainian military would join Russia to oust Zelenskyy’s regime, and that Kiev would be his in a couple of days.

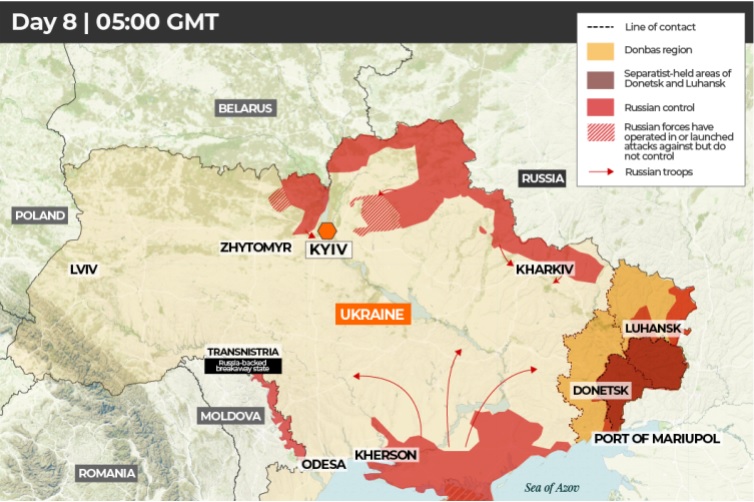

According to all analysts, the battle seemed lost in advance for Kiev, given the huge gap between the two armies in warfare capabilities. In the early days of the war, Russia took control of large parts of Ukrainian territory, particularly on four fronts:

- Toward Kiev, running along the two banks of the Dnieper River from Belarus and from Russia

- In the north-east in the direction of Sumy and Kharkiv

- In the Donbass, to expand the territory controlled by the separatist regions and from Russia

- In the south from Crimea to conquer the whole Ukrainian shore; toward the east to make a junction with the Donbass, toward the west to take Odessa and reach Transnistria

But this aim did not consider the efforts made to improve the Ukrainian army since 2014 (new material, training, etc.), the operational capabilities of the soldiers who had been involved in the Donbass for years, the Ukrainians’ national spirit and culture of resistance, and the supply of defensive materials such as man-portable air-defence systems (MANPADS) or anti-tank missiles by Ukraine’s allies. This asymmetrical war, involving drones, the internet and those anti-tank missiles, was unexpected and unprepared for by Russia. As a result, the blitzkrieg that was supposed to bring down the Kiev regime to replace Zelenskyy by a Moscow puppet turned into a long storm.

Nothing happened as planned for Russia. Many pieces of evidence prove that the invasion was poorly planned, with a catastrophic lack of instruction given to officers. Hundreds of examples of the absence of specific equipment could be given, such as the lack of the Antonov An-2 remotely piloted planes that are supposed to be used as targets to detect Ukrainian’s air defence; without them, real planes with real pilots were sent to the frontline with no preparation and shot down in numbers. The two airborne assaults dedicated to the opening of a new front failed, elite soldiers were caught in traps like in Irpin, and thousands of men as well as an inconsiderable amount of military equipment was lost in plain sight of the international community. The transparency of the situation offered by social media, which had never been seen before, revealed poor Russian capability and a bad strategy, which led to serious logistical problems.

The blitzkrieg-like preparation for the war led to a generalised lack of fuel and food supplies on the northern front from the second day. Soldiers had only received a three-day food ration before being sent to the front, and some of them were even carrying their parade uniforms in the direction of Kiev, expecting a parade before the end of February.

The morale of the Russian soldiers also took a hit, as they were unaware of the purpose of this whole charade. Russian action has been undermined by unexpected Ukrainian resistance, tactics and logistics. The Russian army’s advance was reduced to almost nothing after the first three days of the war.

A war of attrition

After the initial state of stupor in the first days of the invasion, the Ukrainians got back on their feet and initiated a general mobilisation. Not only did they resist far more than expected, but they also managed to counter the Russian plan to encircle the capital city. In the west, Russians were pushed back over and over again, remaining around Irpin and Bucha and suffering heavy losses even for elite troops. Head of the Chechen Republic Ramzan Kadyrov himself admitted that Russian tactics do not work and that the Ukrainians were armed “to the teeth with new weapons and ammunition, a new generation of heavy artillery,” and had set numerous traps.

The column dedicated to the east side of Kiev was stopped in Chernihiv, more than 100 kilometres away from the capital city. The northern armies were diverted from their progression southward or through the Donbass to move towards Kiev, with the aim of replacing the column stuck in Chernihiv and encircle the city. This decision created a very long and tiny line of supply from Sumy up to Brovary on a main road within the range of Ukrainian artillery. Russia never managed to gather enough strength to endanger Kiev’s defence, and lost hundreds of men here again.

On the other frontline, almost nothing changed after the first few days. The Russians were kicked out of the city of Kharkiv, which they had taken at the end of February and never managed to reach again or encircle. In the south, the situation evolved a little faster: the Russians had seized the region of Kherson and reached Mykolaiv on the way to Odessa. The coast of the Azov Sea was seized despite heavy fighting in Mariupol. Everyone thought the city could fall in a few days. But Ukrainian groups resisted thanks to the massive bunker built under the Azovstal metallurgical plant.

Russia lowers its ambitions

With the beginning of the spring, there was mud, which reduced the Russians’ movement capabilities. Many other elements have emerged to confirm the initial view of poor Russian preparation: weak tactics conducted by untrained soldiers, lack of secured communication, inability to control airspace, poor coordination of the battalion tactical group (composed of combined-arms manoeuvre unit), and low precision for guided missiles. Ukraine also took profit of the ultra-centralised Russian command structure by specifically targeting generals.

After weeks of waiting, it appeared clear that Belarus would not attack the western part of Ukraine; and the defence force stationed there were therefore free to join the fight around the capital city. Russian withdrawal from Kiev and the north left thousands of men and vehicles on the ground. After the Ukrainian victory of the “battle of Kiev” and the liberation of the whole north, a victory occurred in Mykolaiv on 8 April, saving Odessa and its access to the Black Sea. In Kharkiv, the Ukrainian counter-offensive, launched a month earlier, paid off in the beginning of May, as it pushed the Russians back to the border and liberated Ukraine’s second-largest city.

The Russians had no choice but to revise their ambition downwards, claiming that the Donbass had always been the only target and that the attack on Kiev was just a decoy. With up to half of the involved force dedicated to Kiev and the northern army diverted from the direction of the Donbass, this pretext can be intended just for the Russian audience. The spread of Russian forces was too vast to overthrow the highly motivated and innovative Ukrainian army.

By mid-April, Moscow’s initial plan looked like a complete failure. The invasion almost stopped after the first week. Zelenskyy’s regime is stronger than ever. Far from being demilitarised, Ukraine recovered more than a thousand abandoned Russian vehicles, including last generation assets like T-80 or T-90 tanks, air defence systems, command posts and artillery. After offering Soviet-era modernised weapons, its allies now promise modern Western equipment, such as the American M777 or the French Caesar in the artillery field, with better precision and longer range than any Russian system available. Ukraine also succeeded in its communication thanks to military feats, such as the sinking of the Moskva cruiser, air raids conducted deep in the Russian territory, the successive deaths of generals, spectacular TB2 drone attacks, and even the endurance of aviation. On the other hand, Russia’s proven losses through open-source information alone outmatch the 4000 tanks, armoured vehicles or helicopters, with only 1000 for Ukraine. (4)

Mission Donbass

Putin has no choice: he must save what can still be saved and offer himself a victory at least worthy of the name. Moscow cannot afford to come out of this “special operation” humiliated in the Russians’ point of view. The traumas of the dislocation of the Soviet empire and the disastrous Afghan or Chechnyan campaigns cannot be repeated.

Thus, the Kremlin has refocused its efforts to keep the occupied territories and invade the whole Donbass region. Ukraine’s recovery in the Kharkiv region and around Kherson has stopped. Progress in the Donbass is slow but continuous – around 500 metres a day on average, at an immense human cost. On the 11th of May, the Russians attempted to cross the Seversky Donets River, resulting in what is now known as the most lethal Russian engagement in a day. About 100 armoured vehicles were destroyed and more than 400 soldiers killed. A few days later, they tried and failed again. That is the way things seem to be going in the Russian army: it keeps sending troops and repeating attempts (and mistakes) until it succeeds, regardless of the losses. No matter what happens, the only victory that Russia will be able to gain will be a Pyrrhic victory.

On the other hand, Ukraine is not giving up and continues to resist, conducting punctual counter-offensives with more or less success. Ukrainian fighters in Mariupol surrendered on 16 May, with the evacuation of the fighters from Azovstal. The other frontlines remain active but unchanged.

How did Ukraine manage to make Great Russia suffer?

Obviously, Russian military capabilities have been overestimated. First of all, its Suppression of Enemy Air Defences (SEAD) campaign was a real failure. SEAD is a key element of any military strategy, as the complete control of the airspace is essential for dominance on the ground. Russia’s SEAD campaign was not only too short, but also not effective enough since it took place only during the day and did not reach the entire Ukrainian air defence arsenal, a task that should not have been insurmountable for the Russian bear with hundreds of advanced fighters, strategic bombers and missiles specifically designed to destroy enemy radars.

At the beginning of the war, Russia’s fleet exceeded 2,500 aircraft versus barely 200 for Ukraine. Another problem, already observed in Syria, is Russia’s lack of precision ammunition. Planes are therefore forced to fly at low altitude to deliver “dumb bombs,” reducing efficacy and increasing the risks taken by the pilots. Even the most sophisticated and expensive fighters, such as the Su-34 and Su-35, had to fly within the range of MANPADS, and more than 10 of them were shot down by systems costing only a few thousand dollars. As a consequence, Russians use their air force at a minimum, with only an estimated 150 sorties per day, very far from what we expect from what is supposed to be the second largest air force in the world, supporting 150,000 troops on the ground.

The war in Ukraine revealed the failures of the Russian army, and the list of the surprises could fill pages. Here are a few examples:

- A Garmin navigation GPS system was identified on a Su-34 fighter plane. Such amateur civilian equipment would not be expected in the cockpit of 4.5+ generation aircraft.

- The $100k Orlan-10 observation drones were only fitted with simple Canon cameras fixed with Velcro, and their fuel tanks are in fact mere plastic water bottles.

- Its encrypted communication networks did not function properly, leaking much information to Ukrainian intelligence services and opensource communities.

- Kamov Ka-52 helicopters are not armoured as claimed, with a simple 7.72mm round being able to shut the engine and pass through the cockpit.

- Soldier lack night vision equipment and quadcopter drones.

- Despite the lessons of the 1991 Iraq war, T-80 and T-90 tanks keep the same loading system as the T-72, making them highly vulnerable to anti-tank guided missiles.

- The S-400 air-defence system is unable to stop Soviet-era ballistic missiles or counter Bayraktar TB2 drones.

Russia has suffered from Western sanctions since 2014, following its annexation of Crimea. With the new sanctions, the lack of core components will increase, mostly in the systems that cannot be replaced by local products, specifically in avionics and optics. Programmes like the A-100 radar plane are postponed, while the production of some tanks and air defence systems has stopped. The first consequences of the war can be seen in the Russian military industry. So far, India has cancelled two helicopter acquisition programmes, and China might not buy the Ka-52. Regarding conventional warfare, Russia has no more decisive cards in its hands and all the grand announcements of past years are now outdated. Moreover, the highly marketed weapons dedicated to the nuclear deterrence, or the hypersonic missiles, which were developed at a high cost, are completely useless in the context of a regular war.

If our expectations of the Russian military capability were too high, the Ukrainian ones were much too low. The Ukrainians were more than capable of containing Russian aggression, even in the first week of the war, without the support of allies. The modernisation of equipment was not complete but already advanced; the success of the techno-guerrillas was made possible thanks to an innovative spirit and the training of more than 20,000 Ukrainian soldiers since 2014; and Russian failures gave an additional boost. How could one have imagined that the Ukrainians would be able to fly three types of fighters (Mig-29, Su-25 and Su-27) after 90 days of war? The landscape, the (bad) weather and a high morale also contribute to the resistance capabilities.

To counter Russian efforts in the Donbass and try to retrieve their lands, the Ukrainians now expect a lot from the new systems that are supposed to be introduced by the end of the summer.

What outcome for the end of the war in Ukraine?

Several scenarios are imaginable for the continuation of the conflict in Ukraine. If the level of losses is sustainable, Russia could manage to occupy the entire Donbass and invade the entire Ukrainian coastline, cutting off its access to the Black Sea before reaching Transnistria, a pro-Russian territory in Moldova. Even if this target is much smaller than the initial aim of full annexation, it would be a big win for Russia. A second scenario could limit ambition to the painstakingly-gained Donbass and the currently occupied territories in the south of Ukraine.

Russia would need to practice ethnic cleansing in the occupied territories to manage to control it, as it had done in the separatist region with the forced departure of 1.5 million inhabitants to government-controlled Ukraine since 2014. In view of the strong Ukrainian resistance and increasing support from Western countries, Ukraine could refuse these situations and establish a guerilla with two options: a long-lasting frozen conflict like we saw in the Donbass since 2014, or between the two Koreas; or a continuity of fighting until one of the belligerents accepts defeat.

Other options would be more favourable to Ukraine. As Russia did not announce mass mobilisation for the war, it will become more and more difficult to compensate for the great human losses. Russia deployed half of its 330,000 fighting capabilities in Ukraine, and between 40,000 and 50,000 men have been killed or wounded. The same is true for its military arsenal: the most modern weapons were engaged at the beginning of the war and losses are replaced with unmodernised equipment taken from the depots, with shortage already observed in cruise missiles and guided munitions, for example. Russia’s military capabilities in Ukraine will therefore decline progressively. On the other hand, Ukraine is getting stronger with time, its manpower is already surpassing that of Russia, and its lost equipment will be replaced by more modern and efficient systems. Regardless of the length of the war, the allies’ combined industrial capability is much stronger than Russia’s, especially with the sanctions. Many analysts predict the crossing of the curves by the end of June, even if the Russian 3000-pieces strong artillery capability is hard to counter – unless the Switchblade loitering munitions prove to be incredibly inefficient. In this case, Ukraine could take back all the territories invaded by Russia since February. Some also hope it could recover previously occupied territories in the Donbass or Crimea.

On the military field, we are at the tipping point. Ukraine has overcome all odds, won the battle of Kiev, liberated Mykolaiv and Kharkiv, but is slowly losing the Donbass. This war could last years and cost millions of lives. Nonetheless, the perception of Russia as a huge military power built by Putin over the last 20 years, has been undermined. In fact, the NATO has become more attractive than ever.

(1) Carl Von Clausewitz, Vom Kriege, 1832.

(2) Zbigniew Brzezinski, The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy and Its Geostrategic Imperatives (New York: Basic Books, 1997).

(3) Petr Akopov, “The offensive of Russia and the new world,” Way Back Machine, 26 February 2022, https://bit.ly/39YgE0s (accessed 26 May 2022).

(4) Stijn Mitzer, Joost Oliemans Kemal and Dan and Jakub Janovsky, “Attack On Europe: Documenting Ukrainian Equipment Losses During The 2022 Russian Invasion Of Ukraine,” Oryx, 24 February 2022, https://bit.ly/3GiOmdk (accessed 26 May 2022).