|

| [AlJazeera] |

| Abstract The election of Hassan Rouhani has been the start of a new path for Iran’s foreign policy, including its relationship with Washington. This paper discusses three schools of thought prevalent in Iran’s regime towards the US, ranging from those who believe America is addicted to hegemony, to those who believe there is inherent antagonism between Iran’s Islamic system and the West to those who represent a more moderate stance, including current President Hassan Rouhani. The paper concludes that if relations between Iran and the US improve, there will likely be pressure from the US on the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and its other allies in the region to minimize tension with Iran, particularly in order to solve conflicts in the region from Lebanon to Afghanistan without losing Saudi or Iran as allies. |

Introduction

When Hassan Rouhani took office in June last year, Iran faced numerous challenges. Chief among them were Iran’s convulsive relations with the West, in particular the US, the crisis over Iran’s nuclear program and an economy which was spiralling downward. Rouhani, along with many economists in Iran, believed that mismanagement by Ahmadinejad’s team was partly responsible for the state of Iran’s economy, but that sanctions had also made a profound impact. It was based on these challenges that Rouhani simply but effectively outlined his election platform for the masses clamouring for change in Iran's future after eight tumultuous years of Ahmadinejad’s presidency. “It is good for the centrifuges to spin (enriching uranium), but the wheels of Iranian factories should also spin,” he remarked during his campaign. (1)

In the aftermath of his landslide victory, Iran’s Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, endorsed the concept of “heroic flexibility” in relations with the United States. This was in contrast to prior years of mostly uninterrupted opposition to direct talks with Americans, especially since 2003. Moderate Hassan Rouhani's determination to alter the trajectory of Iran’s foreign policy from confrontation to cooperation coupled with Ayatollah Khamenei’s cautious support of engagement with the US paved the road to an unprecedented meeting between the two states’ foreign ministers.

Iran’s three schools of thought towards the US

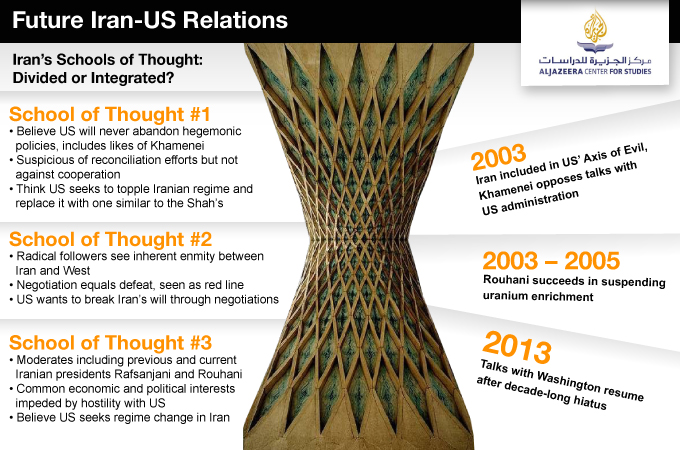

There are three schools of thought in the nezam (Iran’s political system) with respect to relations with the United States. The first school of thought, to which Ayatollah Khamenei subscribes, is that America cannot escape its addiction to hegemony. As a result, the Islamic Republic of Iran rejects American domination and believes that the US’ strategic objective is to topple the nezam and establish a new system that, like the Shah’s regime, accepts a patron-client relationship.

Because of their deep-seated mistrust toward the US, advocates of this school of thought view any American sponsored reconciliatory efforts with utmost suspicion. However, this school of thought does not categorically reject rapprochement between the two countries.

In March 2013, Ayatollah Khamenei stated that he is “not opposed” to direct talks with the United States but he remarked that he is also “not optimistic.” (2) On January 9, 2014, he remarked, “We had announced previously that if we feel it is expedient, we would negotiate with Satan [the US] to deter its evil.” (3)

Even with respect to restoring Iran-US relations, Ayatollah Khamenei has publicly remarked, “We have never said that the relations will remain severed forever. Undoubtedly, the day relations with America prove beneficial for the Iranian nation, I will be the first one to approve of that.” (4) He has articulated several similar statements. This necessarily demonstrates he has not closed doors on dialogue and even restoring relations with the US.

Ayatollah Khamenei's pessimism about the outcome of talks and cooperation with the US is not unfounded. Rather, it is from his own historic experiences between the two countries.

Before and after the tragic events of September 11, 2001, Iran conducted direct talks with the United States. Although the talks centred around the situation in Afghanistan, Iran sought to open dialogue and cooperation with the United States. The focus of the talks after September 11 was directed toward cooperation between the two governments aimed at unseating the Taliban. Through the Northern Alliance in Afghanistan, the armed opposition group to the Taliban which was equipped and financed by Iran, Iran effectively cooperated with American-led forces in bringing down the Taliban.

In later efforts to establish Afghanistan's new government, Iran’s contribution was crucial. Ambassador James Dobbins, leader of the US delegation, explains the role of Javad Zarif, Iran’s then-Deputy Foreign Minister and Iran’s current Foreign Minister, as follows: “Zarif had achieved the final breakthrough, without which the Karzai government might never have been formed.” (5) But only a few weeks later, President Bush branded Iran as one of the components of the “axis of evil.”

Then, in 2003, Iran unofficially signalled a “grand bargain” to the US government in another rapprochement effort aimed at resolving all of the disputed issues between the two states. That bargain was also declined by the American administration.

Later in 2003, the monumental dispute between the two countries over Iran’s nuclear program emerged as a centre of contention. The author of this report acted as the Deputy of the then Secretary of Iran's National Security Council, Hassan Rouhani, as well as the spokesman for Iran’s nuclear negotiating team. Between 2003 and 2005 in negotiations with the EU3 (Britain, France, Germany), the major obstacle to reaching an agreement was US insistence on the notion of “zero uranium enrichment inside Iran.” The situation was defined well by Britain’s Foreign Secretary at the time, Jack Straw. Speaking at a panel in the BBC in July 2013, he remarked, “We were getting somewhere, with respect, and then it’s a complicated story, the Americans actually pulled the rug from under [President Mohammad] Khatami’s feet and the Americans got what they didn’t want.” (6)

These experiences led Ayatollah Khamenei to believe that Americans are not prepared to compromise over less than “regime change” while he has, over and over again, acquiesced to opening doors for reconciliation to no avail.

The second school of thought, advocated by radicals, asserts that there is inherent antagonism between Iran’s Islamic system and the West. They argue that the way to success is sheer resistance until America recognizes Iran and respects its identity as is. In their view, negotiation with the United States means accepting defeat and must be considered the ultimate red line.

Hossein Shariatmadari who advocates this camp argues the US insists on bringing Iran to the negotiating table in order to destroy its stature as the “flag bearer of struggle against global domination.” (7) He asserts that Iran’s resistance to the US has made it the role model for all freedom fighters in the Islamic world, viewing that:

“America’s intention is to break this model apart by talking to Iran…They want to give this impression to the movements in the Islamic world that the Islamic Republic of Iran, your strategic and ideological ally…[after long years of resistance] had no final choice other than to sit with and talk to America.” (8)

The third school of thought represents the moderate camp. Notable figures ascribing to this trend are Iran’s former President, Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, and the current Iranian President, Hassan Rouhani. They agree with the notion that the US seeks regime change if it is able to do so. However, they contend that enormous common interests exist, both economically and politically, and that these interests mutually suffer as a result of hostile relations between the two countries. For example, they maintain that jihadists and extremists are a common and dangerous adversary of Iran, the US, and its allies in the region. Therefore, they should cooperate to root them out or at least contain them. To underscore this school of thought, they believe that through serious negotiations and engagement, it is indeed possible to utilize the common interests and reshape the US’ position toward Iran's nezam.

In an interview during his election campaign, Rouhani said, “Eight or ten years ago we could talk about reducing tensions with the US…Now, we are in the stage of hostilities…we must first diminish the hostilities back to tension and then try to defuse them.” (9)

Over the last 25 years, or since the death of Ayatollah Khomeini, the first and third schools of thought have oscillated between cooperation and rejection while the second camp has relentlessly sought to prevent enduring talks and any notion of improving relations between Iran and the US.

Rouhani’s position in Iranian politics

Among politicians, few possess Rouhani’s credentials and background. In the 1980s during Iran's war with Iraq, he held close relations with the commanders of Iran's military and the Islamic Revolution Guards Corps (IRGC) when he served as Deputy Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces. He served for eight years as Head of the Foreign Policy committee of the Iranian Parliament, 16 years as the Secretary of the National Security Council and was Iran’s leading nuclear negotiator between 2003 and 2005. This places him in extremely exclusive company with political figures possessing a deep understanding of Iran’s foreign policy as well as scrupulous details of Iran’s nuclear crisis.

Additionally, having served without interruption for 23 years as Ayatollah Khamenei’s representative in the National Security Council until his election last June, Rouhani was in contact with every corridor of power in Iran.

These qualities place Rouhani in a rare position in Iran, empowering him to negotiate with the power elite, including the Supreme Leader, while he also negotiates with world powers over Iran’s nuclear standoff. The temporary and voluntary suspension of uranium enrichment between 2003 and 2005 resulted from Rouhani’s negotiating skills, even though Ayatollah Khamenei was fundamentally reluctant about suspension.

It is therefore prudent to claim that Rouhani today, as a moderate who is determined to end the nuclear issue and move toward détente with the US, holds a particular position in Iran’s politics. Cementing his place in Iran’s politics is the backing of Iran's Supreme Leader and considerable support of the Iranian population. The US’ calculations should account for Rouhani's stature and sincere efforts if their real intention is to untie Iran’s impossible nuclear Gordian knot through diplomatic processes.

Challenges facing US-Iran relations

Due to profound mistrust between the two states, although perhaps more palpable on the Iranian side, the fate and future trajectory of relations between the US and Iran will undoubtedly be determined by the outcome of the Geneva accord, known as the “Joint Plan of Action.” As far as both parties are concerned, there will be no other bilateral engagement activated unless a comprehensive deal is reached on the nuclear issue. The reason is simple. Rouhani and his team, including his Foreign Minister, Javad Zarif, cannot convince the Supreme Leader and other followers of the first camp that even if the United States' ultimate intention is to topple the regime, these intentions could be reshaped through honest and serious talks, negotiations and confidence-building measures. A meeting between the US Secretary of State John Kerry and Iran’s Foreign Minister Javad Zarif parallel to the Munich Security Conference in February 2014 confirms this viewpoint. The situation in Washington is very similar because Obama cannot convince Congress and pressure lobbies for a Grand Bargain with Iran.

According to reports, in response to Kerry raising the issue of Syria and urging Iran “to show a willingness to play a constructive role in bringing an end to the conflict,” (10) Zarif said that “he did not have the authority to discuss Syria and the focus of the meeting was on nuclear negotiations.” This was a clear response to US policy preventing Iran from participating in the Geneva II conference on Syria. (11) However, Iran has been prepared to participate unconditionally in multi-lateral talks to find solutions for ending the tragedy in Syria.

In November 2013, Iran’s Supreme Leader offered supportive and forceful remarks to Iran's negotiating team. “No one should consider our negotiating team as compromisers…These are the children of revolution…No one should belittle an officer doing their job…We strongly support our diplomacy team,” he said. (12) Despite this resounding support, there are still sporadic hardliner critics of the manner in which Zarif and Rouhani have handled the nuclear issue thus far. However, the mood in general is silenced, adopting a wait-and-see approach. The main challenge to the Geneva interim accord and ultimately, a peaceful resolution to Iran’s nuclear crisis, comes from abroad, primarily the United States.

The pro-Israel lobby and some members of Congress insist that putting pressure on Iran is the only way to force change in its behaviour. Senator Menendez is a primary sponsor of the sanction bill called the “Nuclear Weapon Free Iran Act,” which in practical terms is a complete oil embargo on Iran. Menendez argues that, “Current sanctions brought Iran to the negotiating table and a credible threat of future sanctions will require Iran to cooperate and act in good faith at the negotiating table.” (13)

But this argument is flawed, espousing that sanctions were the only reason why Iranians were persuaded to sign the Geneva interim agreement. The reality is that despite all the pressure that sanctions would impose on Iran’s economy, if the US would not have departed from its decade-old policy of “no enrichment on Iranian soil” and would not have accepted compromise on uranium enrichment (even though limited in amount and level) as part of the final agreement, the Geneva interim agreement would not have materialized.

President Obama recognized that insistence on zero enrichment was unrealistic and unachievable. To those who criticize his administration’s acceptance of enrichment in Iran, he says, “I can envision a world in which Congress passed every one of my bills that I put forward. I mean, there are a lot of things that I can envision that would be wonderful.” (14)

That said, there are indications that the US administration also continues to misread the situation and seeks to impose demands that might jeopardize, and result in the failure of the Geneva accord. At a Senate hearing on February 4, 2014, Wendy Sherman, Chief US Negotiator to the talks with Iran remarked, “We know that Iran does not need to have an underground, fortified enrichment facility like Fordow...[or] a heavy-water reactor at Arak to have a peaceful nuclear program.” (15)

These implied demands are deal breakers. Shutting down these facilities would halt a monumental financial and human capital investment that was several years in the making, at the will of a foreign power. This is in total contrast to one of the pillars of the revolution and the Iranian nezam’s resistance to foreign domination. In fact, Iran’s resistance to forgo uranium enrichment emanates from the same worldview. In addition, submitting to such demands would incur high political costs to the decision makers who have constantly linked the nuclear program to the notion of national pride and would make them vulnerable to charges of selling out the country’s dignity.

Javad Zarif wasted no time responding to Wendy Sherman’s statements, declaring that shutting down nuclear facilities was impossible. He said, “Iran's nuclear technology is non-negotiable and comments about Iran's nuclear facilities are worthless… Ms. Sherman should stick to the reality and stop speaking of impossible things even if it is only for domestic consumption ... since reaching a solution can be hindered by such words.” (16) The reality is that specifics of Iran’s nuclear activities are negotiable when it pertains to production levels and extent as well as implementation of surveillance and monitoring measures to ensure that Iran does not divert its nuclear program toward weaponization. However, for reasons mentioned earlier, closing down its facilities is not negotiable. (17)

Meanwhile, the US rationale behind demanding shutdown of those facilities is weak. The first reason is because no country has ever developed an atomic bomb as a member of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) – in other words, under its supervision. Even the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) withdrew from the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT) in 2003 before testing its first nuclear bomb three years later. Iran's government chooses to remain as a signatory to the NPT. If they sought to develop nuclear weapons, they could legally withdraw from the NPT after giving a three month notice to the IAEA and then reconfigure the program for the production of nuclear weapons without legal ramifications.

Second, if Iran intends to acquire atomic weapons covertly, it is illogical they would consider doing so in known facilities under threat of shutdown. Iran would not invite draconian sanctions by insisting on continuing overt nuclear activities. If Iran did not truly desire peaceful nuclear activity, it could close the recognized facilities, appearing to give in to foreign demands, and work clandestinely.

A make-or-break deal

The nuclear deal is pivotal in determining the future of US-Iran relations. The fact is that reaching an agreement between Iran and the P5+1 states is predominantly influenced by agreement between Iran and the US. This is because from September 2003, the beginning of the Iranian nuclear crisis, to September 2013, the US blocked any realistic deal. Therefore, if the two fail to overcome their differences, there will be no deal. And if they succeed, others will most likely come.

Success in striking a deal on the nuclear issue will close a bitter chapter in the troubled relations between Iran and America and will open doors to progress in other areas of dispute. Perhaps more importantly, the two countries could then cooperate on stabilizing the crisis-torn Middle East, from Lebanon in the West to Afghanistan in the East. Together with its allies in the region, the US, in cooperation with Iran, can shape a regional security system to fight the most imminent threat to the interests and security of all parties involved: the rise of extremism and jihadist groups. Under the current circumstances, Iran and the US cannot afford to be enemies because the primary beneficiary of this situation is the escalation of terrorist groups spilling over from one country to the next.

The question remains, what if the Geneva interim agreement fails? In such an eventuality, the US will most likely impose tougher sanctions on Iran. As a result, communication and dialogue between Iran and America will likely cease and the pattern of previous years, meaning the exchange of threatening rhetoric from both sides, will again result in the culmination of hostilities.

This situation would inevitably cause the current moderate policies of Iran to be pushed to the side-lines and radical politics would return in Tehran. Irreconcilable and conflicting policies on both sides of the fence cannot indefinitely continue. History demonstrates that when governments fail to overcome their differences through dialogue, the only other alternative is to seek a military solution.

If the US’ goal is to make sure Iran’s nuclear activities are, and remain peaceful, this is achievable by ensuring the maximum level of transparency and monitoring measures in the framework of the NPT. Given the unstable situation in the Middle East, logic dictates that the adoption of a realistic approach toward the crisis over Iran’s nuclear program will preclude an unfortunate collapse of the Geneva interim agreement which many view as the last opportunity for a diplomatic settlement.

Effects of Iran-US rapprochement on Iran’s neighbouring Arab countries

There are currently two schools of thought in neighbouring Arab countries with respect to their relations with Iran. The one led by Saudi Arabia and some other Arab countries view these relations in the framework of a zero-sum game. This school of thought is concerned that better relations between Iran and the US would undermine their weight in the region in favour of Iran. Therefore, they see themselves in perpetual competition with Iran.

Moderates in Arab countries led by Oman advocate the second school of thought which views better relations between Iran and the US as best serving the interests of all countries in the region. Peace between Iran and the US, according to this school of thought, may open a path for the formation of regional cooperation, stability and peace between Iran and its neighbours, most importantly with Saudi Arabia. This will secure a stable flow of oil which is in the interests of the US and its friends and allies, as well as Iran. Additionally and perhaps more importantly, it creates a unified power to root out a common adversary of terrorism and extremism.

Iran’s moderate mind-set, supported by the Supreme Leader, is in line with Oman’s view. The current Iranian nezam’s doctrine is to reshape Iran’s foreign relations with all countries, particularly Iran’s regional neighbours, in a win-win framework. The moderates in Iran maintain that relations based on a zero-sum game are shaky, unstable and even perilous.

If Iran’s relationship with the US improves, it is rational to expect the US will urge actors in Saudi Arabia and other Arab allies to abandon their confrontational policies toward Iran. This is important because not only does the explosive situation in the Middle East necessitate cooperation between Iran and Saudi Arabia as two regional powers, but also because the US cannot pursue a coherent foreign policy if Saudi, its strategic ally, is in constant conflict with Iran while the US seeks to cooperate with Iran to address the region’s crises from Lebanon to Afghanistan.

Therefore, it is safe to assume that if Iran-US relations are to improve, although previously unimaginable, the US might effectively mediate between Iran and Saudi Arabia and its other Arab allies to open a new chapter after years of strained relations. If the US and Iran can make strategic shifts in their relations, there is no reason Iran and Saudi Arabia cannot follow suit. Such a shift would facilitate establishing a regional cooperation system in the Persian Gulf and beyond.

_________________________________________________________

Ambassador Seyed Hossein Mousavian is a research scholar at the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs at Princeton University. He previously served as Iran’s ambassador to Germany, head of the foreign relations committee of Iran's National Security Council and as spokesman for Iran’s nuclear negotiators. His latest book, “Iran and the United States: An Insider’s view on the Failed Past and the Road to Peace” will be released in May 2014.

Refrences:

(1) International Crisis Group, “Great Expectations: Iran’s New President and the Nuclear Talks, Middle East Briefing N°36, Washington/Brussels,” 13 August 2013, http://www.crisisgroup.org/~/media/Files/Middle%20East%20North%20Africa/Iran%20Gulf/Iran/b036-great-expectations-irans-new-president-and-the-nuclear-talks.pdf.

(2) Associated Press. “Iran's Leader Says He is Not Opposed to Direct Talks with US, But Not Optimistic,” 21 March 2013, http://www.foxnews.com/world/2013/03/21/iran-leader-says-is-not-opposed-to-direct-talks-with-iran-but-not-optimistic/.

(3) Saeed Kamali Dehghan, “Nuclear Talks Showed US hostility Towards Iran, Says Supreme Leader,” 9 January 2014, http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/jan/09/nuclear-talks-us-hostility-iran-khamenei.

(4) BBC, “Profile: Ayatollah Ali Khamenei,” 17 June 2009, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/middle_east/3018932.stm.

(5) Marcus Taylor and Paul George, “Iran Nominee Seen as Olive Branch to United States,” 29 July 2013, http://www.reuters.com/article/2013/07/29/us-iran-usa-zarif-idUSBRE96S0VO20130729.

(6) Alalam, “Straw: US Stalls Accord on Iran Nuclear Program,” Alalam, 5 July 2013, http://en.alalam.ir/news/1491728.

(7) Alef, “US Wants Negotiations for the Sake of Negotiations,” 23 May 2007,

http://alef.ir/vdcg.w97rak9ynpr4a.html?8935.

(8) Ibid, http://alef.ir/vdcg.w97rak9ynpr4a.html?8935.

(9) Mehr News, “Iran-US Relations Must Downgrade From Conflict to Tension To Return Respect to Iranian Passport,” 24 December 2013, http://www.mehrnews.com/detail/News/2066682

(10) Shahir S. Thalith, “Nuclear Issue to Determine Rouhani’s Fate and Iran’s Future,” February 2014, http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/fa/contents/articles/originals/2014/02/iran-geneva-us-policy-rouhani.html.

(11) Samira Said, Nick Paton Walsh and Matt Smith, “Iran Out of Peace Conference on Syria, so Geneva Talks Still On,” 20 January 2014, http://edition.cnn.com/2014/01/19/world/meast/syria-geneva-talks/.

(12) Iran Students’ News Agency, “Ayatollah Khamenei: No One Can Has the Right to Criticize Negotiators, Negotiations Will Not Hurt Us," 4 March 2014, http://isna.ir/fa/news/92081207161/هيچکس-نبايد-مذاکره-کنندگان-ما-را-سازشکار.

(13Senator Robert Menendez, “Twenty-Seven Senators Introduce the Nuclear Weapon Free Iran Act,” 19 December 2013, http://www.menendez.senate.gov/newsroom/press/twenty-seven-senators-introduce-the-nuclear-weapon-free-iran-act.

(14) http://www.haaretz.com/news/diplomacy-defense/1.562259

(15) Press TV, “Iran MPs blast remarks by US Geneva representative,” Press TV, 6 February 2014,

http://www.presstv.ir/detail/2014/02/06/349492/iran-mps-slam-remarks-by-us-envoy/.

(16) Jerusalem Post, “Rejecting US Remarks on Nuke Program, Iran FM Says Fordow, Arak are Non-Negotiable,” 5 February 2014, http://www.jpost.com/Middle-East/Rejecting-US-comments-on-its-nuclear-program-Iran-FM-says-Fordo-Arak-are-non-negotiable-340458.

(17) Press TV, http://www.presstv.ir/detail/2014/02/06/349492/iran-mps-slam-remarks-by-us-envoy/.