|

| [AlJazeera] |

|

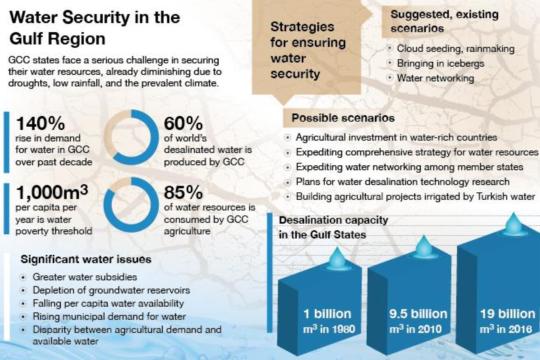

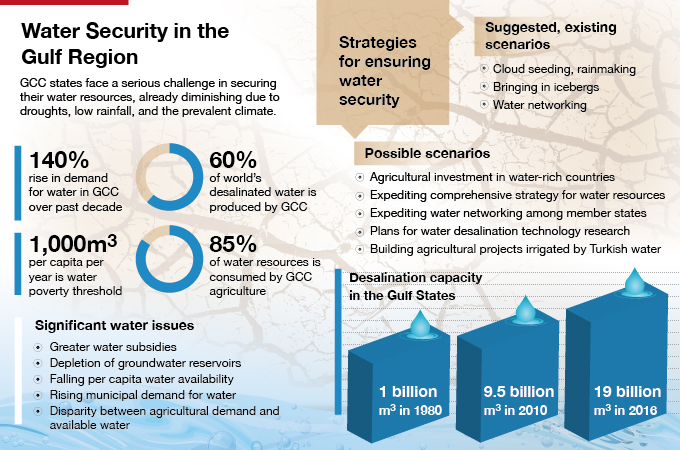

Abstract The difficulties facing member states of the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) in securing sustainable water supplies seem to be increasing and becoming chronic. The fact that natural water resources are rare in this region, combined with minimal precipitation and high evaporation rates, are just some of the reasons why the region’s water resources are dwindling at alarming rates. The problem is compounded by the scarcity of renewable water resources and the limited availability of arable land. The dependency of the GCC states on desalination has severely strained their national budgets and caused irreparable damage to their ecosystems. Based on this analysis, the author recommends that GCC countries waste no time in obtaining a better understanding of the dangers threatening their water supplies, and an appreciation of the grave consequences of water insecurity for their political and social stability. The GCC states must, therefore, develop an early warning system, and improve their readiness to monitor this system. |

Introduction

Lengthy periods of drought, combined with naturally low rates of precipitation, have become major contributory factors in to the serious problems which GCC countries face in securing their water supplies.

The natural features and climates of the six member states are very similar. With the exception of a few parts of Saudi Arabia and Oman, all the states have extremely arid climates with negligible precipitation. Natural water sources are scarce and arable land is extremely limited.

Human factors, such as high population growth, rapid urbanisation, and gigantic industrial and agricultural projects exacerbate the pressure on already strained water-supply systems. The GCC states have had little choice but to secure alternative water supplies. The most important of these are desalination plants, which, as of 2014, accounted for some seventy per cent of the world’s desalinated water output. The member states have also resorted to recycling waste water from sewage systems, and from industrial and agricultural operations. However, their dependence on desalination has placed a severe strain on the national budgets of the GCC states, and caused irreparable damage to local and regional ecosystems.

Understanding water security

In 2000, the second World Water Forum, held in the Netherlands under the banner of ‘Water Security in the 21st Century’, defined water security as:

“Water security, at any level from the household to the global, means that every person has access to enough safe water at affordable cost to lead a clean, healthy and productive life, while ensuring that the natural environment is protected and enhanced”.(1)

Similarly, the Global Water Partnership has defined a water-secure world as vital for

“a future in which there is enough water for social and economic development and for ecosystems. A water-secure world integrates a concern for the intrinsic value of water together with its full range of uses for human survival and well-being. A water-secure world harnesses water’s productive power and minimizes its destructive force. It is a world where every person has enough safe, afford¬able water to lead a clean, healthy and productive life. It is a world where communities are protected from floods, droughts, landslides, erosion and water-borne diseases”.(2)

Various experts suggest that the concept of water security must be measured in relation to a water balance. This refers to the balance between the aggregate water supply (from conventional and non-conventional water sources) over a period of time, and the aggregate water demand for various purposes over the same period. In other words, it is necessary to establish both the input and output quantities of water within a system.(3) With this information, it is possible to determine which of the following possibilities apply:

• A water balance: in which demand equals available supply.

• A water surplus: in which water resources are more than ample.

• A water deficit: in which water resources are less than required.

Finite water resources

Using a quantitative scale, analysts apply the concept of finite water resources to either of two situations. The first is water poverty, where less than 1000m3 of water is available per person per year.(4) The second is a water deficit, which describes a sudden case of demand for water outstripping the available and renewable supplies in an otherwise balanced system, leading to an apparent water deficit, sometimes called a water gap.(5)

Water supplies in the GCC countries

Water in the Arabian Gulf is obtained from three main sources:

• Groundwater, including water in surface wells (which are usually replenished by seasonal rains) and deep wells (which are refilled via ancient geological formations).

• Desalinated seawater, which is supplied via modern, high-tech desalination stations.

• Recycled water, which has been introduced relatively recently and is obtained via wastewater and sewage treatment plants that supply water for agricultural purposes only.(6)

In relation to these water resources, we need to consider the demand for water in the GCC countries and the productive efficiency of their existing water resources. The UNDP’s Arab Human Development Report 2009 indicates that water scarcity is one of the gravest threats to the environment and therefore to human security both in the Arab world generally and to the GCC member states in particular.(7)

If we apply the quantitative scale to the Arab world, at least thirteen Arab countries fall into the water-poor category.(8) Renewable freshwater resources now stand at less than 500m3 per person per year in all six GCC states, while Kuwait is almost completely dependent on non-conventional water resources, such as desalination.(9)

Based on this information, the Arab League Educational, Cultural and Scientific Organization and the Arab Center for the Studies of Arid Zones and Dry Lands have predicted severe water deficits in all six GCC countries by 2030, further forecasting that all the Arab Gulf nations will be classified as water-poor.

To assess the current water situation in GCC countries, this list provides the primary resources of water and basic water demand level, and outlines how available water resources are managed:

Primary water resources

Surface water resources include rainwater and seasonal estuaries. Rainfall rates range from 1mm to 100mm per year. Rain is the main source of replenishment for many of the region’s groundwater basins but about 85 per cent of these basins are in extremely arid areas, and their water is too brackish for agricultural use.

Networks of seasonal estuaries exist across the GCC, with flow rates that vary according to topography, soil, prevailing environmental conditions, and annual rainfall. These estuaries usually flow for limited periods during the year, ranging from a few hours to days or even months. In some very dry areas, they flow only every few years.

Groundwater resources

The quality of groundwater differs from one basin to another. Most sources of groundwater are concentrated in central Saudi Arabia, and are very ancient. Information about the condition of these resources is incomplete. Programs to preserve these basins and ensure that they are replenished with rainwater need to be devised, so they can be tapped when needed. This will require precise record-keeping, follow-up and evaluations. Some of the region’s best-known groundwater basins are the one in the Eastern Region, the Al-Hammad basin, the Riyadh basin, and the Empty Quarter basin, all of which are in (or partially in) Saudi Arabia.

Data collected by the UN Food Programme indicates that groundwater is the primary source of fresh water in Bahrain, Kuwait, Qatar and Saudi Arabia, while surface water is the prevailing source of fresh water in Oman and the United Arab Emirates (UAE).

Unconventional water resources

In their quest to find new resources of water, the GCC states are now among the most prolific producers of non-conventionally-produced water, through the desalination of seawater, and the recycling and reuse of sewage and industrial waste water. Although these processes are hugely expensive when compared to conventional water resources, they are bound to be of great significance in future, as demand for potable water rises and other water resources grow increasingly scarce.(10)

Renewable water resources

Unfortunately, groundwater is currently being used at a rate that far outstrips the pace at which it is able to replenish itself. For example, Saudi Arabia draws 14.430 million cubic metres of groundwater a year, which is roughly 3.5 times the replenishment rate of its renewable groundwater resources. The other GCC member states have reached a similar draw ratio of about 3:1, except for the UAE where that ratio is significantly higher.(11)

This is why desalination has a major role to play in increasing the supply of potable water and satisfying the demand for water in various sectors, with the six GCC states currently collectively responsible for some 60% of the global production of desalinated water.(12)

Rising demand for water

Demand for water in the GCC states has risen by a massive 140 per cent since the mid-2000s. Kuwait tops the list with its increased demand for municipal water. Significant change in the distribution of water allocations in the six member states is unlikely in the near future, but the aggregate allocation for the agricultural sector in the GCC countries is expected to drop from an average of 63 per cent in 1995 to 48 per cent by 2025.(13)

Meanwhile, the combined population of all six states has quintupled over the past few decades, increasing from around eight million people in the 1970s to some 43.5 million in 2010, meaning that the population growth rate is among the highest in the world.(14)

Since the 1980s, accelerating development and population growth have led to the demand for water increasing dramatically from six billion m3 in 1980 to more than 32 billion m3 in 2005.(15)

Sharp increases in population and the ensuing rise in demand for food led most GCC countries to devise ambitious agricultural policies which aim to sustain social and economic development and achieve food self-sufficiency. As a result, the agricultural sector has become the region’s largest consumer of water, accounting for more than 85 per cent of gross water usage in these countries.(16)

It is clear that three interconnected, intersecting factors are responsible for the increase in demand for water in the GCC: population growth, the rising demand for water resulting from developmental requirements, and excessive water consumption associated with consumption patterns in these countries.

National water security policies in GCC countries (water resource management)

A water policy is the framework by which available water resources are managed, and the set of rules and regulations governing water management internally and externally. National water security policies means water policies adopted at a national level by each state within the GCC. From the perspective of integrated water-resources management (IWRM), most reports concerning global water issues agree that three kinds of problems need to be addressed, namely:

• Problems caused by extreme waste of water resources.

• Problems that are well known and for which no economically efficient solutions are available at this time.

• Problems resulting from excessive demand for water, which are now being studied and analysed through governmental policymaking and investment strategies.(17)

A study by the Organization for Economic Cooperation Development indicated that the two main factors preventing better water governance in the OECD countries are the multiplicity of government institutions responsible for water resources, and generally poor governance at all levels.(18) Improving water governance at all levels is key to the sustainable management of water resources, and essential for achieving water security.

National water security policies – those already adopted and those that might be adopted in future – can be divided into supply-based and demand-based policies. In terms of demand-based policies, researchers have been working hard to determine the optimal instruments and mechanisms for water-demand management. These include analysing modern irrigation techniques, the privatisation of the water industry, government subsidisation of water in urban areas, and water quota systems.

Comprehensive reviews of the distribution of water to various sectors, and public water-awareness campaigns derived from the World Bank’s so-called ‘new thinking on water management’ are beginning to replace the more traditional supply-side management approach with a strategy focusing instead on management of demand.(19) Measures to manage demand include:

• Using modern irrigation technologies and saline water for irrigation where possible.

• Developing strains of crops that require less water, and modifying crop mixes.

• Redistributing water supplies among other sectors.

• Rationalising water consumption and promoting water awareness.

The major water issues and challenges facing the GCC countries

The Arab world is a generally arid region, and this is unlikely to change anytime soon. In 1950, renewable water resources in the Arab world amounted to more than 4,000m3 per capita per year. By 1995, this figure had declined to 1,312m3 and reached 1,233m3 by 1998. By 2025, this figure is expected to drop to as low as 547m3.(20)

It is worth noting that since the early 1990s, water consumption globally has been rising at more than double the rate of population growth. A study by the UK-based risk-assessment firm Maplecroft found that fourteen of the eighteen countries designated as having extremely stressed water resources are in the Middle East and North Africa. According to that study, the countries are listed in the following order with 1 being the most stressed:

1. Mauritania;

2. Kuwait

3. Jordan

4. Egypt

5. Israel

7. Iraq

8. Oman

9. UAE

10. Syria

11. Saudi Arabia

14. Libya

16. Djibouti

17. Tunisia

18. Algeria

In addition, the Maplecroft report placed Iran and Qatar’s water situation in the ‘highly stressed’ category.(21) As such, all six GCC member states except Bahrain suffer from severe or high water stress. Clearly, it is impractical for the region to depend on its own natural water resources, as these are inherently just too scarce.

Furthermore, since the groundwater resources of most GCC countries are drawn from basins that cross national boundaries, numerous issues and challenges arise in the management of water, with some of the most important of these including:

• The freshwater per capita index of these countries already stands at less than 500m3 per year (the severe stress threshold).(22)

• The rates of water demand in the municipal sector are far higher than these countries are capable of supplying via their desalination and recycling projects, which already place a considerable strain on their national budgets.(23)

• Reserves in the groundwater reservoirs are dropping and the quality of groundwater, is declining due to its unregulated usage.

• The gap between the requirements of the agricultural sector and available resources is growing constantly: at 85 percent of aggregate consumption, the agricultural sector is the region’s single biggest water consumer.(24)

• Poorly designed water subsidies to urban households caused an increase in the demand for water, placing a huge financial burden on national budgets with virtually no cost recovery.(25)

• According to international reports, water resources have been adversely affected by climate change in the Arab world in general and in the Arabian Peninsula in particular. One of the most important reports on this is by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change of the UNDP and the UNEP.(26)

The future water security of the GCC states

Recent studies predict that global demand for water is going to be around 40 per cent higher in 2030 than it is today, with population growth usually being the biggest cause of increased demand. The world’s population already exceeds seven billion. If the growth rate continues at the current level, approximately 60 per cent of the world’s population will suffer severe water shortages by 2025.(27) The situation is only going to get worse as shown in Table 1:

Table 1: The availability of water in world’s driest places in 2035

|

Country |

2010 population (million) |

Projected 2035 population (million) |

Per capita water supply (m3/person/year) |

|

UAE |

7.512 |

11.042 |

13.6 |

|

Qatar |

1.759 |

2.451 |

21.6 |

|

Saudi Arabia |

27.448 |

40.444 |

59.3 |

|

Bahrain |

1.262 |

1.711 |

67.8 |

|

Yemen |

24.053 |

46.196 |

88.8 |

|

Kuwait |

2.737 |

4.328 |

4.6 |

Source: http://www.beatona.net/CMS/index.php

Four of the GCC’s six member states – including Qatar – are among the world’s top ten countries in terms of vulnerability to severe water scarcity. Kuwait (at only 10m3 per capita per year) tops the list; the UAE (at 58m3 per capita per year) is third; Qatar (at 94m3 per capita per year) is fifth, and Saudi Arabia (at 118m3 per capita per year) is eighth. In addition, Qatar and Bahrain are reportedly already consuming 2.8 and 1.5 times than their available water resources respectively.(28)

Strategies for managing and protecting water security in the GCC

Several imaginative strategies have been proposed to address the aforementioned challenges, including:

• Importing water via pipelines: one example of this was the ‘Peace Pipe’ project, which was on the agenda when the Middle East peace talks began in Madrid in 1991, although many economic and political issues prevented it from seeing the light of day.

• Using modern cloud seeding and rainmaking techniques.

• Moving icebergs to water-poor areas: this is a technically intricate, complex and costly process that is fraught with practical, political and environmental problems.

The World Bank have developed a number of more reality-based development strategies including:

• Agricultural investment in water-rich countries such as Sudan, the Philippines, Ethiopia, Uganda and Turkey. Some GCC countries are already making such investments.

• Investing in agricultural projects in partnership with Turkey on Arab lands that are irrigated by Turkish water, with a framework for revenue sharing.

• Expediting a comprehensive strategy for the development of water resource management policies in all the GCC countries.

• Expediting water interconnectivity projects between the GCC countries, along the lines of existing projects linked to electricity.

• Investment in scientific research to improve desalination technologies.

Conclusion

Potable water is becoming an increasingly rare commodity, and factors such as runaway population growth, poor management and climate change are making water management and allocation exceptionally complex. Desalinated water is invaluable in fulfilling the demands of the GCC member states and their economies. However, any disruptions of water supply would have dire consequences for the political and social stability in the affected countries. A better understanding of the dangers threatening water supplies is crucial, and the capacity of the relevant government institutions to issue early warnings should be publicly accessible. At the same time, preventative and mitigating procedures must be put in place to ensure water security for all, and plans to counter threats to water security should be expedited.

_________________________________________________

*Dr. Taha Al-Farra is a professor at Naif Arab University for Security Sciences.

References

1. Global Water Partnership (2000), Towards Water Security: A Framework for Action, Stockholm.

2. Global Water Partnership (2012) Increasing Water Security: A Development Imperative http://www.gwp.org

3. Al-Ashram, Mahmoud (2001). Iqtisadiyyat Al-Miyah Fi Al-Watan Al-Arabi wa Al-Alam [Water Economics in Arab Countries and the World] Center for Arab Unity Studies, Beirut.

4. This assessment forms part of a continuum whereby areas are considered: water-rich if individuals have access to more than 2,000m3 of potable water per year; water-stressed where individuals have access to 1,000-1,700m3 of water per year; water-poor where individuals have access to less than 1,000m3 of water per year; and extremely water-poor: where individuals have access to less than 500m3 of water per year. For more details, see: Gleick, Peter H (2002). The World’s Water, 2002–2003: The Biennial Report on Freshwater Resources. Washington, DC: Island Press.

5. Mekhemar, Samer and Khalid Hijazi (1996), Azmat Al-Miyah fi Al-Alam Al-Arabi: Al-Haqa’iq Wal-Bada’il Al-Mumkinah [The Water Crisis in the Arab World: Facts and Possible Solutions], Alam Al-Maarifa Series, No. 209, Kuwait: National Council for Culture, Arts and Literature.

6. Abu Zaid, Mahmoud, (1998), Al-Miyah Masdarun Lil-Tawattur Fi Al-Qarn Al-21 [Water: A Source of Tension in the Twenty-first Century], Cairo: Al-Ahram Center for Translation and Publication.

7. UNDP (United Nations Development Programme) (2009) Arab Human Development Report: Challenges to Human Security in the Arab Countries. http://www.undp.org/content/dam/undp/library/corporate/HDR/ahdr2009e.pdf

8. Falkenmark, Malin (1998), Willful Neglect of Water: Pollution, A Major Barrier to Overcome, Stockholm: Stockholm International Water Institute.

9. UNDP (United Nations Development Programme) (2009) Arab Human Development Report: Challenges to Human Security in the Arab Countries. http://www.undp.org/content/dam/undp/library/corporate/HDR/ahdr2009e.pdf

10. See https://www.gulfpolicies.com/index.php.

11. Ibid.

12. Alterman, JB and Dziuban, M (2010), Clear Gold: Water as a Strategic Resource in the Middle East, Washington, DC: Center for Strategic and International Studies.

13. Wallace, JS (2000). Increasing Agricultural Water Efficiency to Meet Future Food Production, Agriculture, Ecosystems and Environment 82: 105–119.

14. Grey, David and Sadoff, Claudia W (2007), Sink or swim? Water Security for Growth and Development, Water Policy 9(6) 545–571.

15. Fathollahzadeh Aghdam, Reza (2008), Why Invest in Eastern Province?, Asharqia Chamber of Commerce. http://www.chamber.org.sa/English/InformationCenter/Studies_and_Reports/Documents/Why_Invest_In_Eastern_Province.pdf

16. Fagan, Brian (2011), Fresh Water Supplies are Going to Run Out, So What Can We Do to Make the Taps Keep Running?, The Independent (UK), 30 June.

17. IPS News Agency (2010), UAE–GCC Summit: Abu Dhabi Water Declaration Calls for Adoption of Modern Farming Technologies, Emirates News Agency, 8 December http://ipsonitizie.it/war_en/news.php?idnews=7963.

18. OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development) (2001), Water Governance in OECD Countries: A Multi-Level Approach, Paris.

19. Rosegrant, Mark W (1991) Irrigation Investment and Management in Asia: Trends, Priorities and Policy Directions. Washington, DC: World Bank.Royal Academy of Engineering (2010(Royal Academy of Engineering (2010). Global Water Security: An Engineering Perspective. www.raeng.org.uk/gws

20. Arab Water Council, (2009), Arab Countries Regional Report to the Fifth World Water Forum, Istanbul. http://www.worldwaterforum5.org

21. UN Water (2011) Statistics, Graphs and Maps: Water Use. http:www.unwater.org/statistics_use.html

22. Falkenmark, Malin (1989), The Massive Water Scarcity Now Threatening Africa: Why Isn’t It Being Addressed? Ambio 18: 112–118.

23. UNDP (2011) Human Development Report. http://hdr.undp.org/en/content/human-development-report-2011

24. Al-Zubari, Waleed K (2008) Integrated Groundwater Resources Management in the GCC Countries: A Review, Proceedings of the Water Science and Technology Association Eighth Gulf Water Conference: Manama, Bahrain, 2-6 March. www.waleedzubari.com/publications/conferences-papers

25. Heathwaite, AL (2010), Multiple Stressors on Water Availability at Global to Catchment Scales: Understanding Human Impact on Nutrient Cycles to Protect Water Quality and Water Availability in the Long Term, Freshwater Biology 55(s1): 241–257

26. The IPCC issues regular reports that are available at www.ipcc.ch/.

27. Qadir, M, BR Sharma, A Bruggeman, R Choukr-Allah, and F Karajeh (2007), Non-Conventional Water Resources and Opportunities for Water Augmentation to Achieve Food Security in Water-Scarce Countries, Agricultural Water Management 87: 2–22.

28. See: http://www.beatona.net/CMS/index.php.