|

| [AL JAZEERA] |

| Abstract This report sheds light on the social backgrounds of volunteer jihadis who joined the Islamic State (IS or Daesh) and proposes that IS, with this “ragtag” assortment it calls a “state”, appears to be a previously unknown and exceptionally unlikely phenomenon. Hence, this phenomenon presents a challenge to established research methods that typically apply when studying this type of group. For example, the circumstantial factor, which is sometimes disregarded, is vital to any attempt to understand the nature and inner workings of this organisation, and cannot be ruled out, because it is part of the slew of social implosions that spawned Daesh in the first place. Based on testimonies the author gathered from young men who joined IS and from their families, the report comes to two key conclusions. The first is that understanding why they joined cannot be built on hard facts alone – in fact, researchers must think outside the sociological and political theory boxes. Second, while al-Qaeda is a nodal organisation, the Islamic State is a flat one, one which overruns territories, subjugates entire tribes, and subsumes entire political parties and battalions that broke away from their military commands. |

Introduction

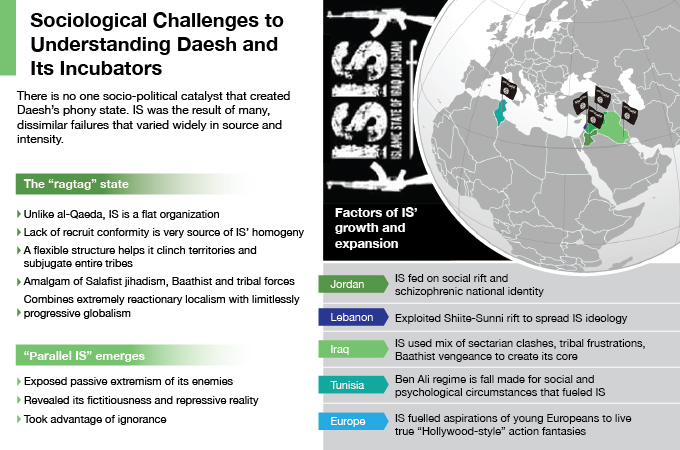

Those who attempt to look for a beginning among the social and political catalysts that helped to create the phony Islamic State (IS) will not find one there. IS, or Daesh, is the result of many dissimilar failures that vary enormously in source and intensity. In Jordan, IS fed on the deep social fault lines that resulted from a weak, schizophrenic national identity. In Lebanon, the Shiite-Sunni rift fanned the flames of IS tendencies within the Sunni community. In Iraq (where the organisation originated and flourished), the disgruntlement of the now-defunct Baath party was the point at which sectarian problems intersected with the frustrations of angry tribes. Looking out west, from the Maghreb all the way to Europe, the stories of IS origin are completely different from those in the Arab world. Tunisia, despite being so far removed from IS’ theatre of operations, is one of the most prolific sources of young, indoctrinated volunteer fighters. The Bin Ali regime’s fall left behind it an immense pile of socio-psychological rubble that the post-revolution Tunisian government has not yet had time to process, with the result that the “caliphate state” was a bypass through which jihadis slipped away. From Europe, there is a curious mix of young men and women who do not necessarily hail from the Muslim diaspora, many of them actually previously Christian, and most of them not from a lower socio-economic status.

The “ragtag” state

IS has presented itself to its recruits as the “state” within which they would find their salvation, creating an unprecedented, almost impossible phenomenon that appears to be unique in the field of humanities. This is probably why Daesh is still an unfathomable entity, regarded as impervious to research instruments that would normally be used to probe this sort of group. Thus, the circumstantial factor, often overlooked, cannot be ruled out if the aim is to understand how the group operates and its processes. The circumstance or context here is the series of implosions that have shaped and nourished the organisation as well as the “ragtag” nature of the group. One of its most popular propaganda pieces, “Flames of War”, illustrates this motley assortment: a European IS recruit joined with the asset of knowing how to build an image and a brand. The Anbari Bedouin with the dishevelled, black hair was a face fit for a Hollywood movie. The Tunisian engineer who made the movie used a team of Jordanian and Lebanese recruits as extras. To wrap it all up, the kidnapped Western journalist was intimidated into mustering every ounce of his television production skills to report on all the madness.(1,2)

IS couldn’t possibly have developed without these “global” puzzle pieces; thus, researchers should begin with the premise that Daesh is more of a charade than the real thing. It is a scene far removed from what is taken as socio-political fact. This scene is one in which the director has successfully embodied the abstract of all these universal implosions. As an example, the horrifying idea of a slave market in Mosul where Yazidi women are sold cannot be explained solely through modern human knowledge. Other branches of science must be brought in, such as medicine, information technology, geography and genetics, to name a few. Moreover, IS has brought about a passive “counter-IS-ism” that festered within the souls of its sworn enemies, the very ones who let their imaginations go wild with images that, as made-up as they are, fit into the same scheme of “IS fiction”.(3)

From the absurdity of “sexual jihad” to the surrealism of the fatwa that stipulated that cows should wear brassieres, the IS phenomenon has been at the centre of countless figments of a collective imagination apparently in dire need of relief from the mental pressure of its own wildness. Daesh presented an excuse for societies to unleash public hysteria, providing some relief – comic and otherwise – from the emotional messes that blackened souls struggling under various forms of oppression.

A parallel Daesh

There is a parallel IS to be found on the fringes of the lands that the so-called Caliphate has claimed as its state – one that has been inaccessible to researchers. Parallel IS groups refers to cultures that contributed volunteers who deserted the familiarity of home and left behind families, friends and countries. An analysis of this culture also unveils a second dimension: there is an IS that hates the real IS, and wants to crush it for “stealing away their boys”. This is the “victim IS”, as opposed to the IS that chops heads, skins people like sheep, and sells Yazidi women to the highest bidder.

To offer a fair analysis, one must remove from the organisation’s victims any fears that they might somehow be responsible for bringing it into being; they are not the womb from which this desert-conquering monster was born. Rather, that womb was a collective, societal, and even global one.

For example, Khalid was the suicide bomber who was barely twenty years old when he blew himself up in downtown Baghdad mid-2014. His mother exemplifies victims that might help researchers better understand the inner workings of the organisation’s psychology.(4) His Lebanese mother from Tripoli said her son had turned pious mere months before he blew himself into smithereens. During the interview, she said she wished to shame her son’s recruiters into coming out from under their rocks. She suffers from a terminal illness (kidney failure) that makes it critical for her to visit a hospital twice a week. Her voice is the only weapon with which she feels she can expose them.

The meta-narrative would claim that Khalid, the young suicide bomber, whom IS recruited in Tripoli, lived in a Shiite-Sunni flashpoint area of the Lebanese city. Like thousands of young men and women, he was angry and frustrated by Hezbollah’s persecution of the Sunnis in Lebanon and Syria. The narrative adds that Tripoli’s slums are breeding grounds for extremists, citing telling facts about the levels of education and income, about mosques that do the recruiting and entities that bankroll it, and about ways to cross borders into Syria and Iraq.

While all of this is indisputably true, the faint voice of Khalid’s mother carries the subtext of another story, the nuances that make Khalid’s story one about a person rather than just a place. The coarse Islamic State was about people long before it was about groups. What happened to Khalid is somehow connected to a larger tragedy behind the voice of his mother and her illness and perhaps this is why he was so easy to recruit. It is not simply the place in which he grew up, either. The preachers whom she says recruited him have no faces and no names. The father whom she says wasn’t there for her and her son is also nameless. There is also the context of a retired grandfather who was looking for a job and an older brother that she worries about constantly.

The bare facts of what happened to Khalid are very similar to what happened to many other young men. Between the facts the mother recounts, which, in and of themselves are hardly enough for a tragic screenplay, there are little details which must not be overlooked. When Khalid’s mother talked about preachers who galvanised young people in old Tripoli’s Tarbiah quarter towards jihad, she casually mentioned a “good man” from the neighbourhood who gave Khalid a job at his shop. This man offered the family a helping hand, and Khalid turned to him for help. He also listened to the man’s advice. As it later turned out, it was he who had been recruiting Khalid all along, and he was the one who sent him off to join IS in Iraq. While the mother protested that their “good neighbour” couldn’t possibly have had a hand in robbing her of her son, and points a finger at unknown preachers, the man had already been arrested and confessed to his ties with outside groups.(5)

Nothing new would have been evident from Khalid’s story without fact-checking, so this new piece of information helps with understanding, at least, how IS recruiters work to gain the trust of the young men being recruited as well as that of their families. Dozens of young people left Tripoli before and after Khalid.(6) They were enticed away by the sectarian dogma as well as people like this recruiter, as were their families. The old photos Khalid’s mother has do not suggest that he might have anything to do with IS. In one of these photos, the young man is seen hugging his mother in the town’s market. In another “selfie”, he looks like any boy dressed and ready for a night out. His mother cannot merge between Khalid the boy and the Khalid the suicide bomber.(7)

Filter of failure

Khalid’s story alone would not add anything new to the overall tale of Tripoli’s destitution. However, it factors in how the Islamic State acts as a filter for various types of failure, the real faces of which can only be seen through individual stories. The Islamic State is not the same organic organisation that al-Qaeda is. On the contrary, it is the exact opposite: it is the breakdown of what is organic in societies into unruly splinters. It is both the epilogue to the “the end of societies” and its prologue.

Interviews with young men such as Khalid, and their families, formulates a key theory-building component: the tragedy didn’t begin with IS, rather, it culminated in it. Politicians cannot possibly explain the creation of IS in the same way Khalid’s mother could by telling her son’s story.

Another interview with a Salafi-jihadi who worked at a gas station in the Palestinian-dominated Jordanian city of Zarqa(8) would indicate that education and meagre income might have had a significant influence on his life choices. Upon listening to Mustafa talk, however, the story is different. He is a young Jordanian man of Palestinian origin, a twenty-four year-old from Zarqa who fought with one of al-Nusra Front’s battalions in rural Daraa. Mustafa returned from Syria about a year ago, and today he thinks that it’s the Islamic State that he should have joined, not al-Nusra.(9)

His story could have made headlines with the standard perspective: a Jordanian of Palestinian origin who lives in Zarqa, whose family had fled Kuwait after the Iraqi invasion in 1990. Being from Zarqa has often been the blameworthy piece of evidence for a young man’s alignment with Daesh, particularly since Zarqa native Abu Musab al-Zarqawi inaugurated the era of slaughter in Salafi jihadism. Mustafa had also said back then that it was his mother who had first encouraged him towards jihad even though she was downright terrified when he left for Syria: his mother, the divorcee, who was angry at his pacifist attitude of piety. While he refused to say too much about his father, or the imam of the neighbourhood mosque (the government employee who’s under the control of the Jordanian Ministry of Endowments, Trusts and Islamic Affairs), Mustafa’s face brightens when he points out how his mother used to yell “Allahu Akbar” [God is Great] whenever Zarqawi carried out one of his deadly operations in Iraq.(10)

He says the sound of her voice as she celebrated Zarqawi’s deadly antics was what drove him. There was also the turmoil within his family – from which he steers the conversation away. A single interview was insufficient to explore the depths of Mustafa’s motivations, but it was enough to indicate that there was more than just economic frustration or the rift between the Jordanian government and its Salafi-jihadi community behind his alliance to IS.(11)

After years of unrest between the government and the Salafi-Jihadi community in Jordan, there grew support for al-Qaeda; however, that has not necessarily automatically translated into support for IS nor can it be the only explanation for IS support in Jordan. Between two visits, more than ten years apart, to Salafi-jihadi activist Luqman Riyalat, who is an al-Nusra supporter in the city of Salt,(12) the man’s Salafist nature had clearly grown weary. In the early 2000s, the young man had arrived to the interview appointment in disguise because he had a feeling he was being followed. He wasn’t easy to talk to back then, either: as a Zarqawist, he drew strict boundaries for any journalistic conversations.

This demeanour changed during the second interview in 2014 at the school he runs in Salt. Now, he is a Salafi preacher surrounded by male and female teachers, who actually makes eye contact with the mothers of the boys and girls who visit him. Luqman’s father was formerly an activist with Jordan’s Muslim Brotherhood, and during the early 2000s interview, he did not want to elaborate on that. During this year’s interview, his father sat next to him with no visible tension between the two.(13)

From interviewing Mustafa, it is clear the Islamic State is an extension of his own personal journey and not necessarily a product of Salafi jihadism or Zarqawism. Mustafa’s life choices and familial, personal and psychological challenges are also not sufficient to explain support for IS. There is a neglected factor: irregularities in an individual’s awareness of public affairs. In other words, there are those individuals who have only their tumultuous relationships with outside values in common, while their reactions to this appear to be extremely varied. They go through the same psychological turmoil, but respond differently to it. And that is where IS comes in, suggesting itself as haven, but for individuals rather than groups.

For example, the Tunisians who are fighting for IS, estimated by some estimates to number more than 5,000, were not the product of the collective Tunisian narrative; rather, they acted out of their rejection of that narrative. Even Tunisia’s traditional Islamic movement, Ennahda, had little or no sociological bearing on Tunisians who dropped everything and left to join IS. More likely, Tunisian mujahideen did so out of dissent against their society and its conformities, even the active Islamic ones. Moreover, they don’t even fall within the parameters that researchers had always detected in jihadi groups: they were neither poor nor marginalised by the mainstream. Even more oddly, the social environments they originated from are more secular than Islamic.

This is where the need to move away from generalised interpretations of the phenomenon becomes more urgent. A more microscopic approach that explores what the meta-narrative misses is inevitable if there is a desire to understand the IS phenomenon. Rasheed, a young Tunisian, couldn’t be farther from the image of the typical devout Muslim.(14) A steward with Tunisair, he is an athletic and handsome young man. However, Rasheed’s brother, Ahmad, two years his junior, headed to Syria a couple of years ago to fight with al-Nusra before eventually joining IS. Here, there is a literal split in the family. They are both from a Zaytunist family (al-Zaytuna school of Islam is the traditional Tunisian school of religious thought, akin to Cairo’s Azhar school), with brothers and sisters who practiced none of the traditional Islamic rites. The only depiction of the hijab in the family was a veil wrapped loosely around the mother’s head.

While there is a clear disconnect between Ahmad and his brother, Rasheed’s story helps increase understanding and goes beyond the normal narrative that Tunisian mujahideen with IS are simply the product of the former regime’s society and embedded in the socio-economic structure established by that regime. Most of them came from the coastal cities where the Democratic Constitutional Assembly (former president Ben Ali’s political party) had enjoyed plenty of influence and backing from the regime’s not-so-poor supporters.

Rasheed, who feels that his brother’s deed has impacted the whole family, described with tension but not outright impoliteness the Salafi preacher who rented the ground-floor apartment in their home, and who, during his and his wife’s stay, managed to recruit his younger brother and almost recruited his sister, too.(15) This is where the story begins to lose its cohesiveness, and this is further evidence that for the Islamic State, it is actually all about the lack of coherence – this is what the group feeds on when recruiting. The preacher who “stole away” their Ahmad had strong relationships with the entire family except for Rasheed. He came along right after the regime fell, and turned the house into a jihadi beehive, according to Rasheed. When he left, he took with him Ahmad and four other young men from around the neighbourhood, located in a suburb of Tunis, to Syria.

On visiting the family’s home, however, it seems this man who stayed for two years left no discernable marks on this household. The sisters don’t wear the hijab, while the father, a retiree and clean-shaven Zaytunist man, had been beaten up and kicked out of the neighbourhood mosque after Salafis stormed it. These events took place while the peculiar Salafi preacher was their tenant;(16) however, Rasheed seeks to explore new possibilities in his brother’s story with jihad. His words and the narrative he tells reveal serious inconsistencies in his belief system. He says, for instance, that the United States was behind the September 11 attacks, which it then used as an excuse to invade the region.

Granted, many other people in the region may share this belief, but in Rasheed’s case, he had a desire to take action. For years, he says, he had been looking for a certain Egyptian journalist who seemed to have all the answers. He even went so far as travelling to Cairo to meet him – unsuccessfully. That journalist wouldn’t even take Rasheed’s calls.(17) In fact, these voids of information can help explain how the Islamic State stormed the region. It converged upon it from previously neglected dimensions. It didn’t ask too much of its newcomers, seemingly saying to them, “Give us your failures, the failures of your countries, societies and families, and come join us”.

There is also the example of Sheikh Hassan al-Shahhal, an advocate of scholarly Salafism in Lebanon, who has always said that violence is not the way of his tenet. His twenty-five year old nephew, Shaker, who was his student and his partner at al-Hidaya Institute, a religious school in Tripoli, left for ar-Raqqah, where he now works as a judge presiding over one of IS’ courts there. When asked why his nephew, his once loyal scholar and companion, had left, Shahhal said that the girl Shaker loved broke his heart, so he fled to IS out of dejection.(18)

The sheer ease with which this sort of incident can occur reflects just how easily Salafism could shift from its “scholarly” dawah level to a more violent paradigm. Shahhal, Lebanon’s most prominent Salafi, believes that support for declaration of a “caliphate” is normal, even if it was Baghdadi who declared it. In other words, between the nephew’s failed courtship and the uncle’s admission of the irresistibility of the caliphate’s lure, it seems clear the reason that prompted Shaker to leave Tripoli for ar- Raqqah is not necessarily because he was lured by “the call”, but rather due to lax confines within which that call easily operated. He was tempted by the appeal, and pushed over the edge by a fleeting, immediate personal failure.

A young Frenchman interviewed by the AFP about his sister, barely seventeen when she left France to join IS, tells a similar story of the alternative that lax confines, disappointment and the lure of the Caliphate offer to a young person. He told the news agency that she didn’t even speak Arabic, not to mention that she comes from a household with nary a trace of religiousness. The only trace they found was a prayer gown his sister had left behind in her room. He pointed out that when he phoned his sister in Aleppo, she told him that her life there was “just like Disneyland”, where she had always dreamed of living.(19)

Conclusion

A prayer gown in the room of a French teenager who dreamed of Disneyland does not explain what happened to that girl any more than Shaker al-Shahhal’s fiance breaking off their engagement would explain why he left for ar-Raqqah. These and the other stories chronicled in this report are just intangible, immeasurable indicators that the quest to join IS must not be confined to hard, sensible facts. Researchers must think outside the socio-political theory boxes in order to build a stronger framework.

While al-Qaeda is a nodal organisation, the Islamic State is a flat one. It overruns territories, subjugates entire tribes, and absorbs entire political parties and battalions that broke away from their militaries. This capacity also facilitates the aptitude for discerning misery and offering an attractive alternative to subsume this misery. In addition to its Salafi jihadism, there are strong elements of Baathism and tribalism in the Islamic State, where extreme reactionary localism and limitlessly progressive globalism go hand-in-hand.

_________________________________

Hazem al-Amin is a Lebanese journalist who reports on jihadi groups. This report is based on his interviews with young people who joined Daesh and their families.

Endnotes

1. Mariano Castillo and Brian Todd, “Who is the English Speaker in ISIS Video 'Flames of War?’ CNN News, 19 September 2014, http://edition.cnn.com/2014/09/19/world/meast/isis-flames-of-war-video.

2. Nolan Markham, “ISIS Releases Hour-Long, Movie-Style Recruitment Feature Film”, 2014, http://www.vocativ.com/world/isis-2/isis-release-hour-long-movie-style-recruitment-feature-film/.

3. Hazem Al-Amin, “Sexual Jihad Between Two Visits: Not an Oriental Fable”, al-Hayat, November 2014., http://alhayat.com/Opinion/Hazem-AlAmin/5428075/%C2%AB%D8%AC%D9%87%D8%A7%D8%AF-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%86%D9%83%D8%A7%D8%AD%C2%BB-%D8%A8%D9%8A%D9%86-%D8%B2%D9%8A%D8%A7%D8%B1%D8%AA%D9%8A%D9%86--%D9%84%D9%8A%D8%B3-%D8%AE%D8%B1%D8%A7%D9%81%D8%A9-%D9%85%D8%B4%D8%B1%D9%82%D9%8A%D8%A9.

4. Author interview with the mother of Khalid, the Lebanese suicide bomber, Tripoli, 10 September 2014.

5. Author interview with Hassan Al-Shahhal, Tripoli, 10 October 2014.

6. Hazem al-Amin, “Tripoli in the Jaws of the Caliphate Again, Boys with New Names Pledge and Blast”, al-Hayat, 14 September 2014, http://staging.alhayat.com/Articles/4588700/%D8%B7%D8%B1%D8%A7%D8%A8%D9%84%D8%B3-%D9%85%D8%AC%D8%AF%D8%AF%D8%A7%D9%8B-%D9%81%D9%8A-%D9%81%D9%85--%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AE%D9%84%D8%A7%D9%81%D8%A9-----%D9%88%D9%81%D8%AA%D9%8A%D8%A9-%D8%A8%D8%A3%D8%B3%D9%85%D8%A7%D8%A1-%D8%AC%D8%AF%D9%8A%D8%AF%D8%A9-%D9%8A%D8%A8%D8%A7%D9%8A%D8%B9%D9%88%D9%86-%D9%88%D9%8A%D9%86%D8%AA%D8%AD%D8%B1%D9%88%D9%86.

7. Ibid.

8. Author interview with Mustafa, a young Jordanian from Zarqa, Amman, Jordan, 4 July 2014.

9. Ibid.

10. Ibid.

11. Ibid.

12. Author interview with Luqman al-Riyalat, Salt, Jordan, 3 July 2014.

13. Ibid.

14. Author interview with Rasheed al-Tunisi, Tunis, 25 October 2014.

15. Ibid.

16. Ibid.

17. Ibid.

18. Author interview with Hassan Al-Shahhal, Tripoli, 10 October 2014.

19. Hazem al-Amin, “Jihad’s Joy Ride to Syria”, al-Hayat, 12 October 2014, http://alhayat.com/Opinion/Hazem-AlAmin/5005048/%D8%B1%D8%AD%D9%84%D8%A9-%C2%AB%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%AC%D9%87%D8%A7%D8%AF%C2%BB-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B3%D9%87%D9%84%D8%A9-%D8%A5%D9%84%D9%89-%D8%B3%D9%88%D8%B1%D9%8A%D8%A9----%D8%B1%D8%A8%D9%85%D8%A7-%D9%87%D8%B0%D9%87-%D9%87%D9%8A.

| Back To Main Page |