|

| [AL JAZEERA] |

|

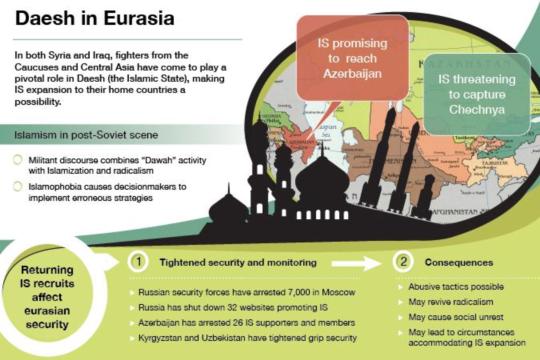

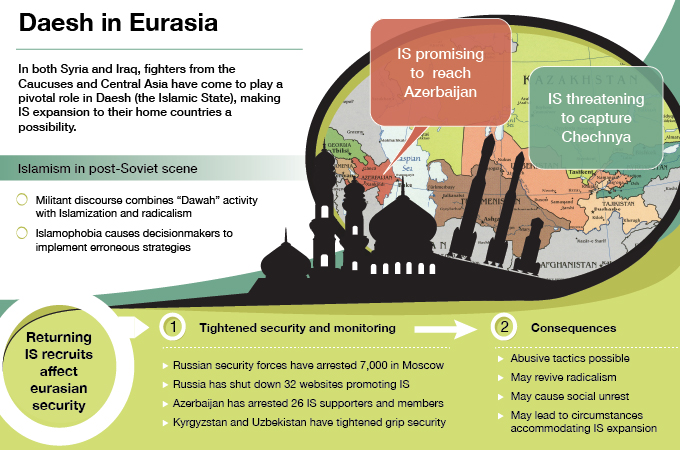

Abstract Of late, armed elements migrating from countries of the Caucasus and Central Asia are increasingly playing a pivotal role in the ongoing struggles within Syria and Iraq, under the command of various armed groups, particularly Daesh. These elements are now occupying central positions in these groups. Therefore, it is worthwhile to inquire about the possible role these elements might play in their respective countries in the event of an end to the current conflict or their possible withdrawal from the conflict zone and their return to their home countries. Endowed with rich natural resources, the countries of the Caucasus and Central Asia are considered important hubs through which oil and gas pipelines to China, Russia, Turkey and Europe pass. Therefore, there is apprehension that these vital interests may be vulnerable to potential strikes. Finally, the analysis delves into the contexts within which regional powers (particularly Russia and Iran) may be likely to exploit the threat from Daesh to bolster their political and strategic relations in the Eurasian arena. |

Introduction

It is believed that IS’ expansion has cross-regional effects that extend beyond the Middle East to the Caucasus and Central Asian regions. Ever since the 1990s, radical movements began to grow as a result of various social and political factors. The most significant of these was the persecution of Muslim societies by the post-Soviet authoritarian regimes, which caused the alienation of the broader population amid unfolding globalisation. These post-Soviet societies could not remain unaffected by the rising tide of radicalism as embodied in the networks of jihadi groups and the developing nexus between al-Qaeda and the IS, which would be reflected in the presence and operations of these groups in the future.

The question that this report seeks to address is the possibility of Daesh impacting the region of the Caucasus (extending from the northern borders of Iran to the southern borders of Russia) and Central Asia (which is contiguous to the Caucasus and extends from the eastern shores of the Caspian Sea to the north-western borders of China). The report will explore the extent to which a regional country like Iran and a continental country like Russia are likely to respond to the probable spread of such influences to their region. It will also examine how apprehensions about rising radicalism are strengthening political and security relations between countries of the two regions. In fact, the potential influence of Daesh will provide opportunities to several regional actors who desire to extend their spheres of influence.

Regional Security in the post-Soviet Era

Barry Buzan defines his theory of the “regional security complex” in these words: “a group of states whose primary security concerns link together sufficiently closely that their national securities cannot reasonably be considered apart from one another”. Another definition conveys the same sense and reads, “a set of units whose major processes of securitisation, desecuritisation, or both are so interlinked that their security problems cannot reasonably be analysed or resolved apart from one another”.(1) These regional security complexes are shaped by a series of competition, balances, alliances, and counter-alliances among political actors within given regions.

Barry Buzan and Ole Waever, the formulators of the “regional security complex” theory, posed a question in their Regions and Powers: The Structures of International Security: “Should we deal with Central Asia and the Caucasus as a single region?” The authors opine that although the two regions share the Turkic languages and the legacy of the Russian language and culture from the Soviet past, they are very distinct from each other. Similarly, while the Caspian Sea with its hydrocarbon and aquatic resources brings them together, their relations are by no means marked by adequate “securitisation” concerns. According to Buzan, as soon as the Caspian Sea is divided among the littoral states and the outstanding dispute is resolved, there will remain little to keep the two regions united. Hence, Buzan looks at them as “security sub-complexes”, each being distinct from the other.(2)

For the purposes of the theory being put forth by this report, Buzan and Waever’s theory needs to be revised in the light of the interaction of at least four factors which make present-day Central Asia and the Caucasus even more interrelated than in the past, in turn having a significant impact on IS’ presence in the two regions.

-

Withdrawal of American forces from Afghanistan: With the withdrawal of American and allied forces, and the gradual reduction of their presence in Afghanistan, the countries of Central Asia and the Caucasus will suffer most from the resulting security vacuum. The withdrawal will provide a greater scope of activity for radical elements, particularly in view of the Pakistani radical groups who have declared allegiance to Daesh.

-

Changes within global jihad networks: IS’ resurgence and its rivalry with al-Qaeda for the leadership and command of combatant groups represents a turning point in the inter-group relations among Jihadi forces. This is bound to have a bearing on its prospective role in both regions.

-

Trade routes and energy transmission lines: The relative importance of the Caspian Sea area as an energy supplier has declined because of the development of new technologies for oil and natural gas extraction. However, the region is still important in relation to the European Union’s energy security plans, especially given East European and Central European EU member-states’ vulnerability to Russian threats. More importantly, the plans for the revival of different silk routes are driving the countries of both regions towards gradual regional integration. The two regions’ geo-economic convergence is bound to expand the scope of intraregional competition and stabilise regional security.

-

Reflections of the Ukrainian Crisis: With increasing tensions between the west and Russia over Ukraine, it is probable that the area of conflict may expand and that the struggle may shift to other fronts, particularly to the Caspian Sea region and southern Caucasus. During the last summit meeting of the littoral states of the Caspian Sea, both Russia and Iran made declarations demanding non-intervention by foreign forces in the Caspian area (in other words, NATO forces). This is the concern that informs the securitisation of the Caspian and surrounding regions, against the backdrop of deteriorating relations between Russia and the West.

Islamist Resurgence in the post-Soviet Era

When discussing Islamist movements’ political role in these post-Soviet societies, it is essential to classify the Islamic movements of this region without falling into the trap of erroneous generalisation. This erroneous generalisation characterises the wider stream of security discourse on the region’s Islamic movements and results in the formulation of inappropriate strategies at the decision-making level. A current tendency within the security discourse in the region about Islamic movements is to lump together “Islamisation” and “radicalisation”, as well as so-called “political Islam” with what is described as “radical Islam”. Much of the strategic discourse appears to lack the ability to differentiate the movements which concentrate purely on dawah (missionary work) from those which engage in political action.(3)

It is true that after the collapse of the Soviet Union, the Muslim societies of the two regions witnessed resurgence towards Islam as a basis for national identity and also witnessed increased performance of Islamic rituals. The Islamic factor did not disappear from these societies even under Soviet rule, which imposed stringent regulations to undermine religion in public life. We know from studies that the Soviet regime tried its best to suppress freedom of expression and performance of Islamic rites during the 1920s and 1930s of the past century, but during the 1950s tried to neutralise religion instead of suppressing it or eliminating it altogether. Thus, Soviet authorities cautiously allowed the activity of some dawah groups until the situation improved remarkably during the 1980s, when dawah networks and groups emerged significantly.(4)

The aim here is to underscore the need to differentiate between different Islamic tendencies specifically in the Caucasus and Central Asia, because the recent arrival of fighters from these two regions to the Arab world has further fuelled the application of reckless generalisations and gross misrepresentation in strategic discussions and media coverage.

The Caucasian Factor in the Middle East Conflict

Many warnings have been circulated about the threat from armed Caucasian elements, especially Chechens, notwithstanding their earlier participation in the Syrian freedom struggle. Some of those affiliated with the IS circulated a video clip earlier this year which declared that Chechnya will be liberated and added to Caliphate. This clip was circulated after IS fighters captured a Russian fighter plane in Syria, and created fears that IS elements would launch their operations in the northern Caucasus and deep into Russia.

As far as foreign fighters are concerned, it is estimated that there are between one and three thousand Caucasians fighting along with armed groups within Syria and Iraq (whether affiliated to IS or al-Nusra Front). The armed Caucasians are divided between those who have arrived from Chechnya, Georgia, Daghestan, and Azerbaijan, and those who migrated from countries of asylum like Europe and Turkey. According to observers, most of the Chechen fighters living in Europe went to the Arab world during 2012 and 2013. Likewise, many of the Chechen students studying in Islamic seminaries in various Arab countries made their way to Syria. Similarly, others proceeded from Grozny to Turkey, while yet others used Bosnia and Kosovo as their transit routes.(5)

Chechen fighters are distinguished by their efficiency in organisational matters, which is an asset for Arab fighters within the IS. They are similarly notable for the skills they acquired during the 1990s in the fields of psychological warfare, visual deception and electronic warfare.(6) As a result, the Chechens have become an important element of Daesh despite their small numbers in comparison with other ethnic groups represented in Daesh.

Chechen Groups

In Syria and Iraq there are four active groups, of which some fall under the banner of the IS and others al-Nusra Front (al-Qaeda in Syria), while still others operate independently:

-

The Army of Muhajireen and Ansar: This is the most prominent fighting group affiliated with IS. This group emerged from a band of migrants who appeared in Aleppo during September 2012 under the leadership of Abu Omar al-Shishani (Abu Omar the Chechen, whose real name is Tarkhan Batirashvili). By merging with other Chechen groups, this group formed the Army of Muhajireen and Ansar in March 2013 and Abu Omar became commander of this group. During late 2013 and early 2014, Abu Omar joined IS.(7) He was appointed by IS as its commander in Syria’s northern region. Thereafter, he was appointed as the general commander of IS forces in Syria.

-

First Muhajireen and Ansar Offshoot: Abu Omar al-Shishani’s IS-affiliation to provoked the first split in the ranks of the Muhajireen and Ansar. Breaking his allegiance with Abu Omar, Salahuddin al-Shishani separated from Abu Omar along with his group, retaining the same name but adding to it the title of the “Islamic Emirate of Caucasus”. This split from Abu Omar is attributed to a conflict between allegiance to Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi (of the IS) and Salahuddin’s allegiance to Doku Umarov, the commander of the “Islamic Emirate of Caucasus”. This group thereafter coordinated with al-Nusra Front militarily but did not enter into battles against IS. Some fighters from this group reportedly split from it to join the aforementioned Abu Omar of IS.(8)

-

Second Muhajireen and Ansar Offshoot: The second group that split from Muhajireen is led by Saifuddin Shishani, who joined al-Nusra Front in late 2013. Saifuddin came to Syria in late 2012 or early 2013 and joined the Army of Muhajireen and Ansar, which was commanded by Abu Omar and became the second-in-command in this group. He split from Abu Omar in July or August 2013 and joined al-Nusra Front in November 2013.(9)

-

The Army of Syria Group: This is a small group which has retained its autonomous status despite its coordination with both Nusra and IS. This group is led by Abu Walid (aka Muslim Shishani or Muslim Margoshvili) who had worked with the Saudi commander Thamir al-Suwailim (aka Amir Khattab) during the second Chechen war. This group is considered to be a strong Chechen group operating in north Syria.(10)

The Azeri Factor

So far as the Azeri Mujahideen are concerned, they too are effectively fighting on IS’ side. They are counted as merely a few hundred (some observers estimate their number at about 300 fighters or a little more). As with Chechnya, IS did not exclude Azerbaijan from its recruitment. IS security officer Abdul Wahid Khuzair has declared that his organisation will arrive in Azerbaijan in the near future and that it will punish the communist governments in Baku, Tiblisi and Moscow. He also claimed that Baku’s oil fields would soon come under the control of his organisation.(11) In addition to Chechens and Azeris, there are reports that Tatar fighters from Volga and Crimea are also participating in the Syrian Jihad.

In spite of the Caucasian presence in IS, a large number of Caucasians are also among the ranks of al-Nusra Front and al-Qaeda in general. It should be pointed out that of late, Daesh has been attracting the Chechens in large numbers, at the expense of al-Nusra Front. The possibility of a compromise between IS and Nusra (al-Qaeda) remains. If it materialises, there is a danger that the Caucasian elements will return to fight alongside each other within a unified group and are likely to coordinate between the allied bands with greater vigour.

The Presence of Central Asian Groups

Like their Caucasian counterparts, particularly the Chechens, the fighters coming from Central Asia to Syria, especially the Uzbeks, possess extensive practical expertise of warfare from their inclusion in the global network of Jihad as well as their presence in various theatres of war, such as Afghanistan and Pakistan. In addition, many of them have undertaken numerous operations at the local and regional levels in the past. Reports indicate that many Uzbek fighters are currently undergoing training on the Afghanistan-Pakistan border before being deployed to Syria and Iraq.(12)

The Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan is considered one of the most prominent Central Asian groups taking part in the theatre of war. Recently it has declared its allegiance to Daesh. The Islamic movement of Uzbekistan began as a dawah group in the Farghana valley, but after Uzbekistan’s independence and the intensity of suppression of religious movements, it acquired a political agenda. The organisation strengthened its structure after moving to Tajikistan during its civil war, which continued from 1992 to 1997, and after the end of the civil war, it migrated to Afghanistan in 1998. During its stay in Tajikistan, the movement aimed to overthrow the Uzbek regime and replace it with an Islamic government. However, after arriving in Afghanistan, the movement discarded its regime-change goal in favour of a global jihad agenda. After the American invasion of Afghanistan, the movement relocated to Waziristan to strengthen its relations with the Taliban of Pakistan.(13) There is also an Uzbek group named Imam Bukhari which operated in the Syrian theatre under the command of IS. Observers point out that most of the Uzbek fighters taking part in Syria’s jihad have come from their countries of exile, particularly Russia, Kirghizia, Turkey and Saudi Arabia.(14)

How could returnees impact regional security?

In the wake of widespread anxiety over IS members’ penetration into Russia, Russian security agencies launched a massive arrest and detention campaign targeting Uzbeks, which was described as racist and biased. On 23 October 2014, 7,000 individuals were arrested in Moscow and thirty-two Russian websites promoting the Islamic State were shut down the following day.(15) Azerbaijan’s campaign to contain the Islamic movement led to the capture of twenty-six Azeris in September this year. Similarly, Central Asian states like Kirghizia and Uzbekistan tightened their security controls. These states’ anti-terror policies to eliminate the “radical threat” appears to have actually exacerbated the situation because the states’ oppressive factors recreate radicalism in these societies. These measures include placing more restrictions on religious practices and limiting the role of religion in public life.

It is plausible that whenever those who are now fighting on IS’ side will return to their home or asylum countries, they may have some influence there, though they cannot pose any serious threat, whether by supporting radical groups or founding new groups, or even through mobilisation of new recruits for dispatch to the Arab world. These regimes’ real fear is that IS may strike at vital installations and transmission lines in the Caucasus, Central Asia and Russia. Likewise, the regimes in power are apprehensive about possible attempts to overthrow the existing governments or to carry out large-scale political assassinations. Although it is possible that such threats may be executed on the ground, there are two major obstacles that would hamper Daesh in this regard:

-

First, enhancement of security coordination between neighbouring countries, particularly the insulation of borders in the northern Caucasus, which makes infiltration and crossing transit points relatively more difficult.

-

Second, the conflict-prone relationship between groups who pledge loyalty to al-Qaeda and others who are now loyal to IS. The split loyalties of these two factions will have a deep bearing on the nature of their coordination after they return.

One possible scenario is that if groups affiliated with IS find a favourable climate to launch their operations in Central Asia, the Caucasus and the Russian interior, they could exploit the security vacuum to launch large-scale strikes against government and diplomatic targets, military-security establishments, and crucial energy pipelines. There are two states in the region where this threat may become real in the wake of Russian intervention in eastern Ukraine:

-

Kazakhstan

As in Ukraine, at present there are apprehensions that Russia may support the separatist movement in Kazakhstan, led by the Russian ethnic minority in the country’s northern region. In 1992, the deputy prime minister at the time, Mikhail Boltorinin, had urged Russia’s president, Boris Yeltsin, to create an independent Russian region in northeast Kazakhstan to accommodate the Russians who were sent there after 1917. Yeltsin did not do so. However, with the exodus of a large number of Russians to Russia, the legal status of Russian residents in Kazakhstan has recently been called into question.(16) The future depends on the stance Astana takes in respect of the Russian designs, and the future equation between Moscow, Beijing and Washington. However, it is unlikely that this scenario will materialise in the short- or medium-term, though the long-term possibility will remain. -

Georgia

By contrast, Georgia, which separated from Russia in 2008, remains vulnerable to Russian intervention, direct or indirect. Recently, relations between Moscow and Tbilisi deteriorated when Russia abrogated its free trade treaty with Georgia in the context of Georgia’s Eurasian ambitions. There are reports Russia is planning to divide Georgia into two and harbours designs for absorbing Abkhazia and southern Ossetia. The outcome of Russia’s plans in Georgia will largely depend on the course adopted by Tbilisi in the wake of the Ukrainian crisis, as well as on Moscow-Washington equations at the regional and global levels.

As mentioned earlier, the oil and gas pipelines in the Caucasus and Central Asia are most vulnerable to attacks from Daesh. Hitting these targets would impact the energy security of the importing countries, with the three most-likely players to be affected China, Russia and Turkey. A summary description of these pipelines follows:

BTC and BTE pipelines

The southern Caucasus gas pipeline (BTE) begins from Baku and passes through Tbilisi before ending in Erzurum (Turkey). A parallel oil pipeline ends at Turkey’s Jihan port. This gas pipeline plays a large role in fulfilling Turkey’s natural gas needs. This is the first Azeri gas pipeline which bypasses Russia. Similarly, the Azeri oil pipeline (BTC) is equally important in transferring Azeri oil to world markets through a route that bypasses Russia. In Azerbaijan, the threat emanates from radical groups, while Georgia is vulnerable to attacks by separatists in the event that a Russian-supported civil war is kindled.(17)

Central Asia-China gas line

This gas line, which consists of three pipelines, is an important supply line of natural gas to western China. This line begins in Turkmenistan passes through Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan and ends in western China. Because it crosses long geographical distances, it is also vulnerable to subversive attacks.

Baku-Novorossiysk oil pipeline

This line begins from the Azerbaijani capital of Baku, passes through Dagestan and Grozny (the capital of Chechnya), and ends at the Russian Novorossiysk Black Sea port. This line also transports Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan’s oil from the Caspian Sea to the Dagestan port of Mahaj Qila from where it is transported onward by oil tankers. Presumably, these lines are likely to be targeted should Caucasian radical groups allied with IS decide to attack.

Would Regional Powers Exploit the Threat of the IS?

Certain states in the Eurasian region view the threat of Daesh’s possible extension from the Arab world to the Caucasus and Central Asia as an opportunity to enhance their political and security situations and include such calculations in their strategic planning. Two states which prominently figure into this context are Iran and Russia.

-

Iran

After signing the interim nuclear accord with western powers at Geneva and the round of talks that followed, Iran aspires to a major role in the Eurasian arena through such forums as the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO). There was a change in the Iranian approach from the Ahmadinejad era to that of incumbent president Hassan Rouhani, when Tehran utilised this forum to press Iran’s claim to be recognised as a partner and strategic player in the region, and as an economic hub not to be bypassed. The presumed threat of Daesh looming over Eurasia and the widening rift between Turkey and its NATO allies have allowed Iran to present itself as a strategic alternative to Turkey, which has hitherto maintained extensive relations with Central Asian and Caucasian countries, given the ethnic ties between them. When the media highlighted Turkey’s reluctance to rescue Kobani’s Kurds from Daesh’s onslaught, Iran presented itself as a partner of the global war against so-called terrorism, from Syria and Iraq to Ankara. Thus, as a rival to Turkey, Iran has tried to exploit the current state of affairs in the Arab world to further its own interests by competing with Turkey in its eastern neighbourhood.Since Iran began its rapprochement with the west, Tehran has also tried to improve relations with Baku, aimed at deepening security coordination with Azerbaijan. Lately, Tehran has tried to involve Baku in Iran’s Eurasian economic projects. In light of American and European pressures on Azerbaijan in respect to its human rights record, Tehran is inclined to wean Baku away from the west and align it with the Iranian-Russian axis away from Turkey.

Similarly, Iran’s recent relations with Turkmenistan were greatly improved when the defence ministers of the two countries met on 16 September 2014, their first meeting since 1991. Furthermore, Iran’s relations with Tajikistan and Uzbekistan have improved considerably in recent times. In this context, Iran will use the IS threat to strengthen its position as a strategic partner in the Eurasian arena.

-

Russia

There are a number of regional and global factors that motivate Russia to revive its engagement with its Eurasian neighbourhood. These factors are Russia’s determination to combat western security and military influence in Central Asia and the Caucasus, particularly in the wake of the Ukrainian crisis; and its desire to enhance its presence in the area, particularly after a spurt in China’s role in the post-Soviet era and by implementing different strategies from those employed against the west.Aligning with Vladimir Putin’s ideal of a “Russian World” (Russkiy Mir), Moscow is trying to attract the post-Soviet countries towards strategic and economic forums such as the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO), the Collective Security Treaty Organisation (CSTO), the Eurasian Customs Union (ECU), and the long-established Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS).

With the rise of Daesh, the Kremlin is likely to exploit the fears and apprehensions of weak post-Soviet states to persuade them to join the Russian-sponsored regional security arrangements so that Russian forces can be deployed to protect their borders and pipelines. However, the states in question, probably fearing a repetition of the Georgian and Ukrainian scenarios, will be cautious so as to avoid a situation in which Russia absorbs parts of their territory. As pointed out above, it appears that an Iranian-Russian axis is taking shape in the southern Caucasus, given their geo-economic and geo-strategic consensus to address their mutual concerns about NATO intervention in the Caspian Sea region.

Conclusion

The challenges posed by the proliferation of IS’ radical threat are not limited to the Caucasus and Central Asia, but rather extend to the way powerful states in the neighbourhood manipulate these security concerns for their own interests. Moreover, the hype over the presumed radicalism threat is bound to lead to more restrictions on the exercise of religion in these societies, which in turn breeds more radicalism. For sustained social cohesion, these states must formulate a comprehensive strategy of political and economic reforms to usher in democracy, enhance freedoms and civil liberties, and facilitate development towards greater transparency and social justice. At the regional and global levels, the Caucasus and Central Asian states should seek greater intelligence and security cooperation to closely monitor the activities of IS-affiliated groups and individuals on a large scale.

___________________________

Tamar Badawi specialises in International Relations and Central Asian affairs.

Endnotes

1. Barry Buzan and Ole Waever, (2003). Regions and Powers: The Structure of International Security, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 44.

2. Ibid, 419.

3. John Heathershaw and David W. Montgomery, The Myth of Post-Soviet Muslim Radicalization in the Central Asian Republics, Chatham House Russia and Eurasia Programme Research Paper, (London: Chatham House, November 2014), 6. click here.

4. Ibid, 4.

5. Mairbek Vatchagaev, “Recruits From Chechnya and Central Asia Bolster Ranks of Islamic State”, Eurasia Daily Monitor 11(154, 4 September 2014), Jamestown Foundation,

http://www.jamestown.org/programs/nc/single/?tx_ttnews%5Btt_news%5D=42786&tx_ttnews%5BbackPid%5D=759&no_cache=1.

6. Theodore Karasik, “The Chechen Factor in the Islamic State: The Immediate threat to the Russian Federation’, Azeri Daily, 21 September 2014, http://azeridaily.com/analytics/1091.

7. Guido Steinberg, A Chechen al-Qaeda? Caucasian Groups Further Internationalise the Syrian Struggle, German Institute for International and Security Affairs (SWP), June 2014, 4, http://www.swp-berlin.org/fileadmin/contents/products/comments/2014C31_sbg.pdf.

8. Ibid.

9. Ibid.

10. Ibid.

11. Theodore Karasik, “The Impact of ISIL on Azerbaijan”.

12. Munthir Badr Haloom, “The Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan joins Daesh”, al-Araby al-Jadeed, 10 October 2014, http://www.alaraby.co.uk/politics/bf286e98-ac70-45c2-af75-d359d3e53d06.

13. Bayram Balci, “From Fergana Valley to Syria - the Transformation of Central Asian Radical Islam”, Eurasia Outlook, (Moscow: Carnegie Moscow Center, 25 July 2014), http://carnegie.ru/eurasiaoutlook/?fa=56252.

14. Ibid.

15. Mairbek Vatchagaev, “Moscow Suddenly Shows Concern About the Growing Influence in Russia of Islamic State”, Jamestown Foundation, 21 October 2014, http://www.jamestown.org/single/?tx_ttnews%5Btt_news%5D=43028&no_cache=1#.VGasYvmUe6I.

16. Paul Goble, “How Moscow Is Playing the Russian Autonomy Card in Kazakhstan”, Jamestown Foundation, 21 October 2014.

17. For more information on the role of energy in southern Caucasus see this author’s report at the following link: http://studies.aljazeera.net/reports/2013/11/201311196273252194.htm.

| Back To Main Page |