The escalating confrontations in Lebanon, especially in the north, between the forces supporting President Bashar al-Assad and forces supporting the Syrian opposition and rebel groups can be attributed to a number of inter-related factors. Some of these factors are internal, related to the Lebanese themselves, while others are external related to the Syrians and international powers currently involved in the conflict over the fate of the Syrian regime.

The current crisis in Lebanon is characterised by the lack of a coherent internal political system or external safety network to prevent the Syrian crisis from engulfing Lebanon and harming the very fabric of Lebanese society.

Approaching the Prohibited

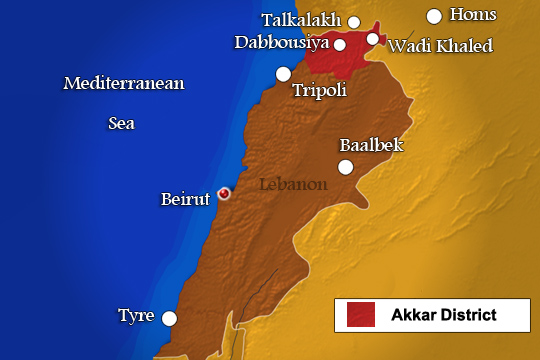

Last year, a number of incidents took place in Lebanon against the backdrop of the events in Syria, such as the kidnapping in Lebanon of the former Syrian Vice-President, Shibley Al Isemi (90 years of age), who has been in opposition to the al-Assad regime and whose fate is still unknown. Apart from scattered security incidents, the most serious incidents have been sporadic clashes between Jabal Mohsen and Bab Al Tabanah in Tripoli. Since April 2012, however, the situation has worsened and the accelerated tensions could at any moment become explosive.

An example of such an incident is when an Onarga shell is fired suddenly from the Bab Al-Tabana (of Sunni majority) in the direction of the Jabal Mohsen neighbourhood (of Alawite majority that is pro-Assad) or vice versa, followed by an exchange of shots for a few hours, that only ends after the intervention of the army. The situation then returns to a cautious calm, awaiting what the Lebanese call “the next round”, a term that had prevailed during the long destructive civil war in the 1970s and 1980s. Following eight "rounds" of fighting between the two sides in Tripoli and scores of deaths and injuries, institutions in Tripoli met to address the issue of the combatants and to open the way for security forces, including the army and internal security, to take control of the situation. It is noticeable that the military alone cannot afford to intervene without a clear public political cover, because it is considered by many as belonging to a particular category of partisan denomination. The same applies to the internal security forces that also belong to a particular category of partisan denomination but in opposition to the first. Hence, the deployment of both the army and internal security together is a means of political cover for the security forces, and to ensure it is seen as a political decision to put an end to the fighting in Tripoli and only after the crisis had threatened to spread across the country.

Another example of the divisions in Lebanese State security institutions over the Syrian situation is the young man Shadi Mawlawi who was arrested by public security forces upon leaving the Office of the Minister of Finance, Mohamed Safadi, on charges of belonging to Al-Qaeda. As the news of the arrest spread, the Sunni Salafi groups organised sit-ins and protests in the Bekaa and the north and threatened, particularly the Public Security Service headed by Major-General Abbas Ibrahim (who is considered to be close to the 8th March Group), with violence if Mawlawi was not released. After two or three days Mawlawi was in fact released, welcomed by his supporters as a hero, and was even driven in Minister Safadi's car to visit Prime Minister Najib Mikati. We do not know whether the release was a result of political pressure and the threats by Sunni groups, or whether the investigation simply did not find any evidence against him.

Another example is the killing of Sheikh Abdul Wahid and his assistant when they passed a Lebanese Army checkpoint. There were two versions of the incident: one is that an infiltrator officer in the army was incited by a certain group to commit the crime, intending to ignite the fire of sedition, and another version is that the army opened fire in self-defence and in response to a fire started by the Sheikh's escorts. Three officers and eleven from the army were arrested for interrogation, and the case was suspended pending the results of investigations that may not necessarily be published.

The tensions are not confined to the Lebanese forces alone, but have expanded to the relationship between the Syrian regime and the Lebanese government. Syria’s envoy to the United Nations, Bashar Jaafari, had sent a letter to Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon on 16 May 2012, in which he accused Lebanon of harbouring terrorist elements of Al-Qaeda and the Muslim Brotherhood who are threatening the security of Syria. In his response to the letter, Prime Minister Mikati said: ‘The aim of the letter is to fuel conflict in Lebanon, whose government is doing its best in the fight against terrorism, border control and to address the loopholes,’ referring to the abuses that have emerged from the Syrian side of the border. It should be mentioned that the Lebanese Defence Minister, Fayez Ghosn, had earlier said: "There are elements of Al-Qaeda in the Bekaa town of Arsal,” which was refuted by the Interior Minister and head of government Marwan Charbel.

Against the backdrop of a divided government, the influence of the political sectarian elite and public activity on the streets, protest banditry has multiplied and the pace of sectarian rhetoric has increased along side it, pointing to the possibility of a hidden hand, or rather fingers, trying to ignite the fire of sedition.

Who is manipulating who?

There has been an exchange of accusations by both parties. On the one hand the 8th March Group has accused other nations of conspiring against Syria using northern Lebanon as a rear base to attack the Syrian regime. This is possible, according to the group, because a buffer zone can be established in the north and the border Arsal of Bekaa as well, but has not been due to the inability of the state and the sectarian nature of the region. Thus, the smuggling of weapons and militants they believe occurs from Lebanon to Syria, evidenced by the seizure (by the Lebanese army) of a ship in Salaata carrying weapons from Libya to the rebels in Syria. This occurrence, for the group, is another example of Salafi Sunni efforts against Syria and Shiite Hezbollah in order to achieve a balance with the latter's strength in the north versus the south and its suburbs. The strategic objective behind the occurrences, according to the 8th March Group, is to disarm the resistance through dismantling the Iranian-Syria-Hezbollah alliance. The efforts at spreading chaos in Lebanon would likely lead to a sectarian war, and thus achieve the aims of those seeking to eliminate the resistance from the inside by distracting from the real threat, Israel, and being occupied instead with fierce internal war.

On the other hand, the 14th March Group believe that Syria is behind the recent tensions. This is based on the fact that President al-Assad had repeatedly threatened that an earthquake would strike the region if the Syrian regime collapsed. This earthquake stems from Lebanon, which is located in the area’s geo-political shift. The Lebanese policy of distancing itself from the situation is no longer feasible. The Syrian regime has asked the Lebanese government to improve its treatment of displaced Syrians, to prevent the smuggling of arms, and to arrest those accused of assisting the rebels, and in general to support the demands of General Aoun, among others. The arrest of Shadi Mowlawi, the well known activist in the Syrian revolution, was a sign that the Lebanese government would succumb to Syria's demands. In Jabal Mohsen, it is the Syrian supporters who are causing a disturbance in order to attract Syrian military intervention. This was directly expressed by the call of Rifat Eid, President of the pro-Syria Arab Democratic Party, for the intervention of Syrian forces. The sectarian war in Lebanon distracts international attention from Syria and eases the pressure, thus giving the regime the opportunity to suppress the revolution.

Security tensions reached Beirut itself and began to hover over Sidon, the capital of the south, and Ein el-Hilweh refugee camp in particular. Amid such a volatile atmosphere the Lebanese have called for dialogue in order to defuse the situation and rescue its summer season tourist market, especially after Kuwait, Qatar and UAE called upon their citizens not to travel to Lebanon. However, the convention on the crisis on 11 June is not likely to lead to a solution to the Lebanese crisis, which is organically linked to its sister-state Syria, but may bring the country to a standstill, pending any improvements.

These rising tensions will require an internally coherent political system that can overcome or at least reduce the aggravation of the situation.

The End of the Doha Agreement

The Doha agreement of May 2008 gave birth to a cycle of political agreements based on the Lebanese traditional phrase "no winner no loser". This first manifested through the election of the compromise candidate President of the Republic General Michel Suleiman, in the presence of a legion of ambassadors and senior officials from powerful foreign international and regional countries. This was meant as an expression of a new international concern for Lebanon to fill the vacuum left as a result of the Syrian withdrawal in 2005. This was followed by parliamentary elections in the spring of 2009 from which a consensus government was formed, in the autumn of the same year, headed by Saad Hariri. This was then followed by a breakthrough in the relationship between the latter and Damascus encouraged by Saudi Arabia and the West.

On 13 January 2011, the above-mentioned government was dissolved upon resignation of a third of its ministers, supporters of Syria, against the backdrop of a worsening relationship between the latter on the one hand, and Saudi Arabia and its Lebanese allies (especially the Future Movement) on the other hand. The overthrow of the government was a fatal blow to the Doha Agreement and was seen as a Syrian attempt to monopolize Lebanese affairs and to return it to the era of trusteeship. Then, the formation of a new government headed by Najib Mikati, without the participation of the 14th March forces, became the last blow to the said agreement. Unfortunately for this new government, it had hardly commenced its duties when its Syrian sponsor itself entered, as of 15 March 2011, into a bloody crisis that is worsening by the day.

Despite its slogan "We are all for action", the Mikati government was ineffective from the time of its formation as a result of differences over competing interests, and because of the lack of regional attention (from what was called "S.S", Saudi and Syria). This is aside from high levels of anticipation overshadowing the internal Lebanese situation as a result of the crisis in Syria, despite the Government's stated policy of "self-distancing". This policy has been practically successful in protecting the country, whose connection with this crisis remains theoretical or deferred at least, despite the declared split among the Lebanese between those anti- and those pro-Syrian regime. Sayyid Hassan Nasrallah confirmed in a speech his support for the Syrian regime and of President Bashar al-Assad, who sponsored and protected the resistance and whose country is, according to Nasrallah, being attacked as part of a foreign Zionist–American conspiracy that aims to eradicate all those who resist Israel. Meanwhile, the 14th March forces have announced their support for the Syrian people who have rebelled against an oppressive dictatorial regime under which the Lebanese had long suffered during the era of its trusteeship.

The Lebanese government, especially its president Mikati, seems to avoid taking important decisions and stands, waiting for things to clear in Syria. The developments in the neighbouring country will impact on the relationship between the 8th and 14th March forces, in addition to the prohibited sectarian sedition, or military confrontation.

What exacerbates the situation is that the internal Lebanese forces are not doing anything to mitigate the repercussions of the Syrian crisis. Instead, they are using it to alter the internal balance of power.

A zero-sum game between the 8th and 14th March

Despite the dominance of Syrian events on the daily political, social and media fronts, the security situation in Lebanon had remained stable for most of this year. But the prevailing political discourse takes the direction of more support for the Syrian regime on the one hand, and more adoption of Syrian refugees to Lebanon by those who are mostly anti-Syrian regime on the other hand.

The Middle East, despite some positive signals resulting from the Iranian-Western negotiations on the nuclear issue, appears to be heading towards a crisis: political clashes between the GCC States, Turkey and the Arab League on the one hand and Iran and Syria, backed by Russia and China, on the other hand. In Lebanon, polarisation is becoming intensified and exacerbated where the zero-sum game between the two forces of the 8th and 14th March is sacrificed. What is achieved by the Syrian rebels on the ground is seen by supporters of the 14th March Group as a victory for them in the face of the forces of the 8th March, that will manifest when the Syrian regime invades Baba Amr, for example. When the foreign ministers of the GCC States meet to declare that the policies of Iran and its nuclear program are the cause of instability in the region, the 14th March forces usually counter by declaring that the weapons of Hezbollah are the cause of instability in Lebanon. Thus, regional and international alliances are at the core of Lebanese politics, and Lebanon is only a reflection of the greater regional and international polarisation.

This is not the first time that Lebanon has become vulnerable to external crises; it has always been a mirror of what is going on in the rest of the region, which is in turn a reflection of the international axis. But this time, the danger is that sectarian sedition may lead to another civil war, which may ultimately cause even more destruction to Syria, Lebanon and the region at large.

Concern over these risks is shared by senior international officials such as Secretary-General of the UN Ban-Ki-moon and the UN envoy to Syria, Kofi Annan, the Secretary-General of the League of Arab States, Nabil al-Arabi, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov, US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, and others. Warnings of the potential for civil war are being declared on a daily basis since it became clear that Kofi Annan's mission was heading toward failure.

Expectations of the Future

It is difficult to predict the turn of events in Syria in the foreseeable future and beyond. But it is certain that a military solution is unlikely in all its forms; NATO would not intervene militarily in Syria the way it did in Libya, after the criticism it received after the Libyan intervention as well as the resulting caution on the part of regional and international players. The Syrian opposition has failed to agree on a unifying framework with which to move forward and the possibility of a representative body based on an agreed common vision. In fact, it is more correct to speak of Syrian "oppositions". From the side of the regime, despite adopting a hard-line and insistence - since the beginning of the crisis - on the use of military and security resources to suppress the uprising, the opposition(s) have increased in strength and expansion day by day with no signs of decline or retreat; all the while it is clear that the Syrian regime will not be brought down by armed force.

We are now facing an international dispute on Syria, no less than the struggle between the regime and the opposition in which neither is able to dominate the other. Thus, the solution to the crisis in Syria will not be possible unless an agreement is reached between Moscow and Washington. The Russians will only accept a solution that secures their interests that have repeatedly been violated by the Americans in more than one crisis, in more than one region in the world. As the US believes that time is working against its opponents, it is likely that serious negotiations on the Syrian solution will be postponed to after the US presidential election. Then, several scenarios for a solution will be on the table, depending on the existing balance of power. This may come in the form of the Yemeni or Russian experience, or a solution particular to the Syrian situation, such as a regional and international conference called by Moscow, for example.

During this period, Lebanon will continue to drum to the rhythm of the Syrian crisis without entering into a civil war, whose bitter taste is well-known to the Lebanese, but without civil and political peace and stability either. Therefore, the Lebanese arena will remain ready for the mobilisation of its military in the case of sectarian sedition or the more welcome realisation of the regionally desired objective of an agreement in which all the parties find interest and necessity. If the Syrian crisis is not over before the upcoming parliamentary elections in the spring of 2013, it is possible that the Lebanese will postpone the elections, under one pretext or another, pending the resolution to the situation in Syria.

It is most likely that stability in the Syrian situation will lead to stability in Lebanon. With the prevalent zero-sum game there will be a winner and a loser, and the loser will try to compensate for its loss, given that it represents a major sect and trend, or a party capable of destabilising a fragile country whose sectarian system is based on quotas and links to external forces. The victor will try to strengthen its gains by preventing the defeated party from recovering. Hence, the need for regional attention through an agreement similar to that of Doha or Taif, based on the new balance of power arising from the emerging Syrian situation.

Therefore, it is essential that the international-regional settlement of the Syrian crisis should include Lebanon in its terms, given the close interconnection between the two countries, and in order to avoid leaving the Lebanese arena vulnerable to the effect of a transition in Syria, which will undoubtedly be difficult.