|

| [AlJazeera] |

| Abstract Thousands of people were injured or killed in South Sudan after clashes broke out in its capital, Juba, between pro-regime Salva Kiir supporters and forces loyal to fired Vice President Riek Machar. Nearly 200,000 citizens have fled their homes as a result. Mashar and a number of leaders from the Sudan Peoples’ Liberation Movement (SPLM) were fired last July by President Kiir, who announced recently that his forces successfully foiled the coup attempt led by Machar. Machar denies the coup allegations and accuses Kiir of attempting to oust his political opponents. International and regional mediation efforts are probable given the conflict is limited to power and wealth divisions and because the two sides share close tribal origins (Kiir from the Dinka tribe and Machar from the Nuer tribe) – neither is capable of ousting the other and one cannot rule the country without the other. Finally, the costs of conflict would be larger than the benefits of agreement, so this paper argues it is in their respective best interests to come to a consensus on oil exports, a key area of contention. |

Introduction

On December 15, 2013, clashes broke out between President Salva Kiir’s forces and forces loyal to fired Vice President Riek Machar in Juba, South Sudan. Thousands of citizens were killed or injured, and the United Nations estimates nearly 200,000 have been forced to flee. The day after clashes broke out, Kiir called a press conference to declare regime forces had successfully put down a coup led by Machar, Kiir’s former deputy ousted in July 2013 with a number of other Sudan Peoples’ Liberation Movement (SPLM) leaders. Machar denied the coup allegations and accused Kiir of attempting to oust the opposition. Mass arrests followed, with dozens of SPLM leaders and government ministers detained in the campaign. The arrests coincided with a meeting of the National Liberation Council (the movement’s highest military and political authority), during which Kiir harshly attacked Machar and his group, causing members to walk out in protest. Thereafter, there were rumours of Machar’s arrest and a group of his supporters in the National Guard reacted by firing their guns in protest, triggering violent clashes.

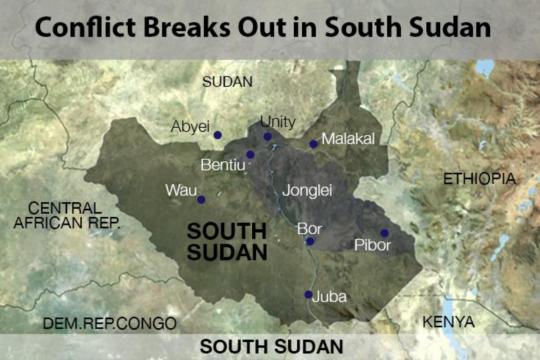

The conflict quickly spread to other areas of the country. Media outlets reported that Machar’s forces had taken over Bor, the capital of Jonglei state; Bentiu, the capital of Unity state; and Malkal, the capital of the Upper Nile state – all strategic cities because they fall in oil-rich areas. While Kiir’s forces took back Bor and Malkal, Malkal fell to Machar’s forces again on December 31, 2013.

Cracks within SPLM

The SPLM began in 1983 and claims a rocky history – at one point, former SPLM leader John Garang executed all his fellow founders of the movement, sparing only the current president, Salva Kiir. An agreement mediated by Machar is what retained Kiir as vice president under Garang and subsequently earned him the presidency when Garang’s helicopter crashed in the Amatong Mountain range in July 2005. The movement also split in 1991 and then reunited again in 2001 after the failure of the Khartoum Peace Agreement. While there are cracks in its structures, it remained fairly cohesive during the confrontation with North Sudan. The solidarity vanished, however, when South Sudan split from the North, and was replaced by rivalry and a power struggle. The three key factors of disagreement within SPLM will be discussed in this section of the paper.

1. Lack of collective identity in South Sudan

The fact remains that the unity formed in South Sudan during the fight against the North was simply tribal leaders joining ranks in rebellion against a common enemy. As soon as the binding reason disappeared, the ties became weaker and tribal alignments emerged within the ranks of the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA), an army housing dozens of armed factions representing tribes such as the Dinka, Nuer, Shilluk, Mandari, Barya and Acholi. The military was supposed to vanish gradually from the political scene, transitioning the country from a revolution to a state with civilian politicians. However, there remains no firm commitment to this objective, and many politicians in South Sudan have only retained their position due to their military capabilities.

2. Differences over relationship with North

South Sudan faces the threat of an economic collapse, and Kiir argues that there is a need to settle disputes with the North in order to ensure a stable relationship, one which secures the flow of oil through pipelines and ports in the North and trade between the two countries. Machar’s group argues that the focus should be an alliance between them and SPLM-North Sector. Further complicating the disagreement is Abyei and Kiir’s refusal to recognise an SPLM-led referendum annexing the region to South Sudan.

3. Differing personalities and leadership skills between president and vice president

While Kiir views himself as a seasoned combat fighter and cautious intelligence hawk, he lacks knowledge of post-independence state management at a time when the country needs experienced political leadership able to fulfil promises of development. Machar, on the other hand, also has military experience but sees himself as an intellectual and university professor with knowledge of what it takes to run a state at a historic juncture.

When Machar made an early announcement that he would vie for the presidency of SPLM in the 2015 elections, Kiir took this as a challenge to his authority and position as the country’s president. In order to protect himself, Kiir accused a number of SPLM leaders of corruption then deposed them. For example, SPLM secretary general Pagan Amum was arrested, interrogated and stripped of his executive and political powers. The presidential office also sent letters to 75 SPLM leaders, demanding the return of billions of dollars in public funds they had supposedly stolen.

Implications for Sudan

The power struggle in Juba will surely affect the stability of Khartoum. The cooperation agreement which would have allowed South Sudan’s oil exports to pass via Northern pipelines and ports and opened border crossings and customs to allow exchange of goods and services has been interrupted by current developments in the South. This is due to several factors which will be discussed in this section.

1. Border demarcation

The border extends for about 2,000 kilometres. The two sides had planned to open ten crossing points and customs offices, but the recent conflicts have made it a security hazard posing unavoidable threats to Sudan. Furthermore, the scale of priorities for authorities in Juba has shifted from the border and customs points to handling the security situation that puts their very existence on the line.

2. Threats by Machar’s forces to oil wells in Unity and Upper Nile states

Chinese and Indian firms have evacuated employees working in oil fields in the two areas, making oil revenues yet another casualty of the conflict. Oil became a major factor when Machar demanded that an international party be charged with the supervision, production, marketing and monitoring of revenues from southern oil so Kiir’s government wouldn’t be the key beneficiary. Both Sudans rely on oil – South Sudan relies on it as the source of more than 98 per cent of its revenue, while the Sudanese government has projected it will collect $4 billion in revenues from pipelines and ports used by South Sudan to export oil this year.

3. Displacement of South Sudanese citizens

A large number of citizens continue to flee, many of them to the north in search of safety, even though the Sudanese economy is exhausted and cannot absorb the pressure of these new arrivals.

4. Machar’s forces are sympathetic to the Revolutionary Front fighting the Sudanese government in Darfur, Nuba Mountains and Blue Nile

Differing political views and Kiir’s willingness to reconcile with Sudan’s government has created tension with Machar, particularly given that Machar’s forces sympathize with armed forces fighting the North in Darfur and will likely cooperate with the Revolutionary Front. The Front in turn will take advantage of the loosened political and security conditions and carry out military strikes which will add to Khartoum’s security burden.

5. Security threat in South Sudan will be felt by entire region

There are a number of other crises in the area – from Somalia to Mali to South Sudan and Sudan as well as the Central African Republic, all bringing with them active forces including Jihadi groups, the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) and foreign forces such as the US, Israel and China. This latest conflict increases tension in the region.

Slippery Slope

Several scenarios could emerge from the complicated and unpredictable situation in South Sudan. Data collected from the present situation indicates the following scenarios could emerge. Important to note is the linked fate and slippery slope of the possible scenarios – if the first does not result in outcomes, there will be a decline to the second, and so on.

1. Multi-level mediation led by IGAD countries could succeed with support of the African Union and US and UN envoys to the two Sudans

While Kiir unconditionally agreed to mediation, Machar demanded the release of his comrades held in Juba before any such meeting. Several things must occur for this scenario to succeed: the two parties must agree to sit at the negotiating table together and to a cease fire; an acceptable constitutional foundation with power rotations must be laid; and tribes cannot be left out of the equation given their social leverage and military fuel in the current conflict. Time is of the essence – any extension of the conflict will bring a higher risk of fighting along tribal lines and identity killing.

Some have suggested an inclusive transitional government with a Constituent Assembly that will enact the constitution and establish rules for the peaceful transfer of power as well as wealth and power distribution. As mentioned earlier in the paper, this scenario is highly likely given the closeness shared by the Dinka and Nuer tribes – neither can rule the country against the will of the other. It is also in the best interests of regional and international powers who want to prevent the conflict from spreading.

2. South Sudan could be placed under international trusteeship

In the event that mediation fails to bring the parties together, the international community may mandate an outside party to manage the state’s affairs, preserve security and provide safe haven for victims of war until consensus is achieved. Uganda, the US, the UN and Kenya have already become involved. For example, Uganda has intervened militarily and provided direct support to Kiir’s forces in the face of his opponents – partially due to their economic interests in the country’s large market. Another example is the passage of a UN resolution that will double their forces stationed in the South to about 13,000 troops.

Part of this scenario is not about only about interests, however. It is also about a moral responsibility for the failure of the South Sudan state – the US and Uganda served as regional and international midwives that initially delivered this new state and thus bear some responsibility for the current situation. Israel also needs a stable South Sudan to remain a thorn in the side of Sudan.

3. Country will slip into an ethnically-charged civil war (“Somalisation), mainly with Dinka and its tribal allies fighting Nuer

If both of the previous scenarios do not materialize, it is possible the conflict will slip into an ethnically-charged civil war like the one in Somalia (thus “Somalisation” of the conflict), with the Dinka and its tribal allies fighting Nuer and its supporters. While the Dinka tribe enjoys absolute control of the reins of power given that its members account for 40 per cent of the population, Nuer has a strategic edge given its education and socioeconomic status, its combat capabilities and its strategic concentration in the Unity and Upper Nile states adjacent to Sudan. Unity and Upper Nile control oil wells accounting for 98 per cent of South Sudan’s national income.

Conclusion

The ongoing fighting eliminates the chances of establishing a central state that is able to achieve a minimum level of the rule of law. As a result, South Sudan could become like Somalia, where all the warring factions are militias belonging to warlords fighting for the country’s resources.