|

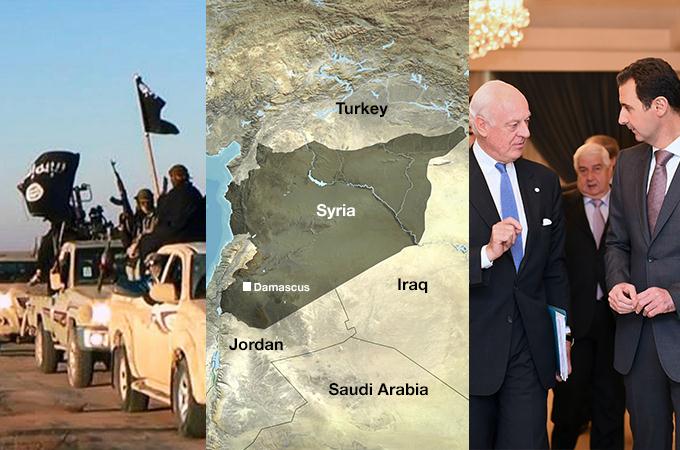

| The international coalition's fight against Daesh's expansion has taken priority to removing the Assad regime in Syria [AlJazeera] |

| Abstract As the Syrian crisis enters its fifth year, regional and international priorities in Syria have changed as a result of Daesh or the so-called Islamic State (IS) group’s expansion. Attempts to repackage the conflict and transform its essence into “fighting terrorism” have increased. In this context, initiatives have been launched to revamp the Syrian regime’s image on the grounds that the conditions that led to the first Geneva Communique no longer exist.(1) However, the prospect that Assad’s regime can be rehabilitated to make it acceptable domestically, regionally or internationally are at best a delusion. The regime’s repressive policies during the years that followed the revolution’s outbreak has made it a polarising rather than a unifying actor, one that has broken all possible lines of political capital and made its institutions even more sectarian during the crisis. In addition, armed groups representing divergent trends have emerged, and they will necessarily play a major role in any future arrangement, one that will not present itself unless power is redistributed in a way that changes the existing system’s structure. |

Introduction

The Assad regime's attempts to imply there is some sort of coordination of between it and the US-led international coalition to eliminate Daesh have increased recently. Bashar al-Assad most recently alluded to this during an interview with the BBC, stating that third parties, among them Iraq, had conveyed messages to Syria on the airstrikes carried out by the US and its allies on Daesh. Despite the US administration’s denials, and the British Foreign Office’s assertion that Assad is deluded, it is clear that the Syrian regime is the biggest beneficiary of Washington’s campaign against Daesh. This has become apparent in many areas of Syria, most notably in Deir Ezzor. Coalition attacks on the province serve as an air force for the regime’s ground troops, which succeeded in halting IS expansion there, and even managed to regain control of some areas that used to be under IS control after the coalition’s attacks. This position paper addresses how regional and international powers’ changing priorities will affect the role and status of the Syrian regime.

Rise of Daesh and changing priorities

The rise of Daesh and its control over large parts of Iraq and Syria around the middle of 2014 represented a major turning point in the ongoing conflict in the region, and had an impact on regional and international actors and their perception of the threats and risks they face, leading to realignments and changed priorities.

The impact on western policy in general, and the US in particular, were clearest, especially with regards to their attitudes toward the various crises in the region. The Iranian nuclear programme and subsequent disputes with Iran are no longer the only determinants of US President Barack Obama’s policies in the Arab world since the US withdrawal from Iraq in 2011. Instead, Daesh has accounted for the most US attention in the region since that time. In fact, it has even become a shared US-Iran interest, as stressed in Obama’s October 2014 secret letter to the Supreme Leader of the Islamic Revolution, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. In the letter, Obama referred to a “common interest” between the two countries: the fight against Daesh in Syria and Iraq.(2)

Tehran’s exclusion from the Paris Conference in September 2014, which paved the way for the establishment of the international coalition to eliminate IS, was a result of pressure exerted by Arab countries, particularly Saudi Arabia. However, it did not prevent the existence of Iran-US coordination, including the exchange of critical intelligence on Iraq. Regarding Syria, some reports have hinted that Washington and Tehran reached an understanding under which the US pledged that coalition fighter jets would not target Syrian regime’s forces, while Iran guaranteed the security of American experts dispatched by the Obama administration to Iraq to train and advise Iraqi forces on US strategy to defeat Daesh.(3)

Naturally, this also means the US’ position on overthrowing the Assad regime has transformed, despite US insistence that the Syrian regime “has lost legitimacy”.(4) Obama’s personal keenness for a foreign policy legacy through a US-Iran agreement on the latter’s nuclear programme has meant he is willing to de-emphasize the Assad regime’s removal in light of US interests after the rise of IS. Washington has nourished the narrative that the only alternative to the Assad regime will be militant Islamic groups, particularly in light of the “moderate” armed opposition’s weakness and the political opposition’s fragmentation abroad.

Similarly, the stances of other western and Arab countries, previously the main constituents of the Friends of Syria group, have changed. This was especially evident after the January Charlie Hebdo attacks in Paris, resulting in the deaths of seventeen people and igniting a wave of Islamophobia that swept across several European countries. As it was, some European countries had already begun changing their positions, prioritising “combating terrorism” in Syria and Iraq after IS’s seizure of the Iraqi city of Mosul in June 2014. The Norwegian government, for example, decided to keep its embassy in Damascus open, headed by a charge d'affaires. Germany and Spain activated intelligence cooperation with the Syrian regime to address threats to their internal security, all the while still affirming the need to launch a transitional phase to resolve the Syrian crisis.(5)

At the Arab level, confronting IS has become a priority above all else. In this context, many Arab states, particularly Saudi Arabia, participated in a September 2014 anti-terrorism conference in Jeddah. That meeting laid the basis for the Paris Conference and the international coalition against IS which was launched a few days later. This trend was also reinforced after IS burned captured Jordanian pilot Muath al-Kasasbeh alive and beheaded twenty-one Egyptian Copts.

Although the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) states say they remain committed to their original position that the Syrian regime’s policies caused the growth of terrorism, they have agreed to prioritise fighting IS even at the expense of the regime’s overthrow. This is despite the fact that many assessments suggest that fighting IS benefits the regime and enhances its chances of survival. Egypt started moving gradually away from its supportive stances toward the Syrian Revolution after the military coup that toppled President Mohamed Morsi mid-2013, and adopted positions that are closer to the Russian perspective by invoking several, similar phrases: “ensuring the territorial integrity of Syria and the unity of its people, rejecting foreign intervention, and preventing state institutions, including the security and army, from collapsing”.(6)

Farewell, Geneva

Many political initiatives and positions reflecting the change in regional and international priorities and concerns have emerged. On the very day he assumed his duties, Staffan de Mistura, succeeding Lakhdar Brahimi as the United Nations special envoy to Syria, called for a truce or for “freezing” the conflict so as to focus on confronting terrorism in Syria.

Russia, Egypt and Iran have all aimed to reproduce the current regime, albeit in different versions. In a bid to launch a dialogue with the Syrian regime, Egypt attempted to unify the Syrian opposition (especially the National Coalition and the National Coordinating Committee), while excluding the Islamist component from it. Russia tried to produce an alternative opposition by fragmenting the National Coalition, courting only certain members. Iran’s agenda was more complex and ambitious – it was interested in creating an alternative opposition, as well as an entity parallel to the Syrian regime through the establishment of armed militias under its sole control, such as the Syrian Hezbollah.

The US stance towards these initiatives and ideas has been most remarkable, even though all of them seek to bury the First Geneva Statement, focus on the formation of a national unity government, and direct both regime and opposition military efforts against Daesh and al-Nusrah Front. After a long period of silence, the US actually issued a statement welcoming Russian endeavours to hold a conference bringing together Syrian parties as a prelude to a settlement. In fact, the American position on the Syrian issue has evolved to the extent of considering Assad’s indispensability in any settlement. In responding to the preparations for conferences engaging the parties of the Syrian conflict in Cairo and Moscow, the US State Department said Assad must be present at the negotiating table, despite the loss of his legitimacy, and praised the Egyptian initiative.

In an official comment on Russia’s initiative, the State Department also confirmed that the US supported all efforts aimed at resolving the Syrian crisis. The Americans have also reached an agreement with Syrian opposition leaders that their fighters must return to Syria after their training, but only to confront IS and not the Syrian regime. US Secretary of State John Kerry welcomed both the de Mistura initiative to freeze the conflict and the Russian initiative to convene a conference for certain Syrian parties ahead of a settlement, and he is no longer as belligerent as he previously was to Assad and his regime. Kerry called on the Assad regime to “think about the consequences of their actions, which are attracting more and more terrorists to Syria, basically because of their efforts to remove Assad”.(7)

Conclusion

Prospects for successfully rehabilitating the Assad regime to make it acceptable domestically, regionally and internationally are a delusion, as expressed by the British Foreign Office in a recent statement. Most serious studies dealing with the evolution of the Syrian crisis do not suggest that the regime can be rehabilitated and maintained without a substantial change in its structure and composition.

The main focus remains on the following four scenarios:

• Stalemate: The conflict continues at the current level of violence and within the current fault lines in light of the inability of any of the parties to win a decisive victory.

• Crippled but victorious regime: The regime regains control of large parts of the country by taking advantage of the military intervention of the coalition forces against IS, while remaining weak, exhausted and absolutely dependent on foreign economic aid from its allies.

• Fall of regime, possible division: The gradual collapse of the regime, with the country entering a situation of chaos that is likely to lead to its division.

• Settlement sans regime: A settlement leading ousting the most prominent regime officials who have been responsible for the disaster that befell their country, saving what can be saved.

None of the above-mentioned scenarios indicates that the regime may maintain its current structure and shape, and regain its original status before the crisis. The regime’s repressive policy during the years that followed the outbreak of the revolution made it a very polarising actor, one that has eroded any semblance of legitimacy. In addition, armed groups representing different trends emerged, and will necessarily be a major part in any future arrangement. This will not happen unless power is redistributed in a way that changes the structure of the existing regime.

___________________________

Copyright © 2014 Al Jazeera Center for Studies, All rights reserved.

Notes

1. The communique had called for the establishment of a transitional authority with full powers as a first step towards democratic change in Syria.

2. Jay Solomon and Carol E. Lee, “Obama Wrote Secret Letter to Iran’s Khamenei About Fighting Islamic State”, Wall Street Journal, November 6, 2014, http://on.wsj.com/1IWkiAZ.

3. BBC News, “Islamic State: Kerry Says Any Iran Strikes ‘Positive’”, BBC News, 3 December 2014, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-30306106.

4. There are several such public statements by President Barack Obama, Secretary of State John Kerry and US Ambassador to the UN Samantha Power. See:

David Kenner, “Rewriting Syria’s War”, Foreign Policy, 18 December 2014, http://foreignpolicy.com/2014/12/18/syria-assad-ceasefires-surrender-nir-rosen-hd-centre-report/, and Aaron David Miller, “Why the US Prefers Assad to ISIS in Syria”, Wall Street Journal, 15 January 2015 http://blogs.wsj.com/washwire/2015/01/15/why-the-u-s-prefers-assad-to-isis-in-syria/?KEYWORDS=bashar+al-assad.

5. Ibrahim Himaidee, “Iran Negotiates with Muath al-Khateeb to Head New Government, Relative Calm in Damascus Before Brahimi’s Appointment”, [Arabic], Al Hayat,7 July 2014, http://www.alhayat.com/Articles/3441310/إيران-تفاوض-معاذ-الخطيب-لترؤس-حكومة-جديدة-وتهدئة-نسبية-في-دمشق-قبل-تعيين-خليفة-للإبراهيمي.

6. See:

Anas al-Kurdee, “Pessimism at Outsourcing the Syrian Issue to Egypt”, al-Araby al-Jadeed, 14 January 2015, http://www.alaraby.co.uk/politics/160f3b2b-648b-43a1-8bad-eb88b0b3b10b , and

Suzy al-Junaidi, “Mikhail Bogdanov: Russia Refuses Any Talk About Toppling Syrian Regime”, [Arabic], Bawabit al-Ahram al-Arabi, 11 October 2014, http://arabi.ahram.org.eg/NewsQ/55697.aspx.

7. Michael R. Gordon and Anne Barnard, “Kerry Supports Syrian Peace Talks in Russia”, New York Times, 14 January 2015, http://www.nytimes.com/2015/01/15/world/middleeast/kerry-backs-syrian-peace-talks-in-russia.html?_r=0