This paper reviews the importance of western Mosul to all parties in the conflict: the Iraqi forces and their allies, on the one hand, and the Islamic State’s forces, on the other, and the obstacles to any of these parties resolving the conflict. It also touches on the extent of their forces and the clear dominance of the offensive forces, and it discusses the military strategies for the battle and potential outcomes in addition to the available options for the Islamic State (IS). It anticipates an end to the fight in favour of the Iraqi forces within a few weeks if the battle and its results progress at a similar pace to that of its first week. This will depend on any unaccounted for variables during the battle that would change the equation on the ground. It concludes by discussing the available options for IS after the battle ends, with the expectation that IS will fight until the end; while its commanders will inevitability lose the battle, this will not eliminate threats to security and stability in Iraq in the foreseeable future.

Introduction

On 17 October 2016, the government of Iraq announced a military operation to recover Mosul following about six months of preparation. The Iraqi forces succeeded in recovering the eastern side of the city on 19 June 2014, after about a hundred days of fierce battles with the Islamic State (IS), which had taken over the city and other cities in the provinces of Kirkuk, Diyala, Salahuddin and Anbar.

On 19 February 2017, the Iraqi government announced the start of the third phase of the "We Are Coming, Nineveh" campaign to recover the western side (the right coast) of the city. Three weeks after the liberation of the entire eastern side, with the support of the international coalition and other air forces, was announced on 24 January 2017, Iraqi forces faced fierce resistance from IS fighters.

The western side of the city is characterised by a high population density, old buildings and narrow alleys, which allow for the potential use of snipers, making it more difficult for the Iraqi forces to move via armoured vehicles. Thus, coalition forces face the option of fighting a high-cost guerrilla war in which IS fighters can excel by neutralising some of the offensive forces’ strengths such as intensive aerial bombardment, long-range artillery fire and bombs with destructive force that can be launched from strategic long-range bombers.

In order to understand the factors contributing to the battle’s progress and outcomes, this analysis will address the importance of western Mosul to both parties, and the obstacles they face in resolving the battle. The paper will also address the extent of the parties’ forces, with the offensive forces clearly dominant, and will discuss the military options for the battle’s trajectory, in addition to its expected outcomes and the options available to IS.

Western Mosul’s importance to the government and the Iraqi forces

Western Mosul is a significant city in Iraq because it is the location of the most important government institutions, such as the city hall and municipality, the presidency of the Nineveh court, a government complex, and the provincial police directorate as well as other institutions, including a sugar mill, Ghazlani camp, Mosul Airport, inter alia. It is also the likely location of IS headquarters, centres of control, and the homes of its leaders and their families since the group took control of the city, which is the last remaining urban stronghold of IS in Iraq.

The recovery of Mosul – Iraq’s second largest city in terms of population – is of paramount importance to the Iraqi government in order to restore sovereignty over the entire territory of Iraq and regain respect for the state and the armed forces. In addition, in the post-conflict stage, it is essential to restore the situation to keep the country from descending into local conflict between the constituents of Mosul, an ethnically and religiously diverse community, which may erupt following a dispute over power and resources between the components of Iraqi society.

Estimates indicate that between 600,000 and 750,000 people live in western Mosul. The presence of these numbers provokes fear that the conflict will lead to the widespread destruction of residential neighbourhoods and a large number of civilian casualties.

Western Mosul’s importance to the Islamic State

On 29 June 2014, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi "declared the Islamic caliphate" from one of the largest mosques in the city of Mosul. Seizing an opportunity to exploit the sentiments of Sunni Arabs who are dissatisfied with the Iraqi government’s exclusionary policies, he presented himself as a protector from the violations of the government and sectarian militias.

The city’s production of cereals constitutes one third of the total production in Iraq, and the region contains several oil fields, which provide a major source of financial revenue for the Islamic State. In addition, it contains land routes linking Iraq to Turkey in the north and Syria in the west, and this road is important to maintaining the territorial contiguity with the Syrian city, Raqqa, the supposed IS capital.

After losing the eastern side of Mosul, the western side became the last remaining part of the city under IS control. The command and control centres, sites for booby-trapping wheels, and workshops for military-industrial weapons and equipment are located in this part along with the families of the organisation’s leaders and fighters.

The forces involved in the battle

|

| [Al Jazeera] |

The comparison in the balance of power between the offensive and defensive forces seems beyond what is customary in military contexts: official US departments estimate that around 2,000 IS fighters are still in western Mosul, as opposed to "about 52,000 fighters, including 29,000 who are fighting actual battles in different areas". There are multiple parties involved in the battle of Mosul within the framework of a broad mobilisation of forces. It is the largest in terms of the number of participating countries, which amounts to about 68 countries with various tasks, including more than 20 countries carrying out air strikes or limited combat operations on the ground since the announcement of the international coalition’s formation on 7 August 2014, less than two months after IS gained control of Mosul and other cities in four Iraqi provinces on 10 June 2014.

In terms of troops, more than 102,000 fighters are confronting nearly 2,000 IS fighters. Iraqi forces constitute the biggest group at about 54,000, while the number of US and non-US troops is 5,000 and 3,600 respectively. Other forces are also involved: there are over 10,000 Kurdish Peshmerga fighters, about 14,000 Sunni tribal fighters, and about 15,000 fighters are from factions of the Shi'a Popular Mobilisation Forces. Less than 4,000 fighters come from the Guards of Nineveh in addition to hundreds of Turkish troops. According to military observers of the battle of Mosul, more than 17 countries have a military presence on the ground in Iraq, including Iran, which announced in Iranian sites on 27 February 2017, "a member of Iran’s Basij named Ashgar Karimi was killed during clashes in Mosul".

Participating alongside Iraqi security forces are UK and US special forces, which are supposed to be purely offering advice and training to lead a new offensive liberating western Mosul. The Iraqi government and leaders of the Popular Mobilisation Forces deny the existence of any foreign combat forces except advisers. The Joint Special Operations Command also denied the existence of "any forces from the United States participating on the ground throughout the restoration and liberation of the city of Mosul". However, on 20 February 2017 during a visit to Iraq, US Secretary of Defence James Mattis confirmed that the US Army would take part in hostilities during the recovery of the rest of Mosul.

Since 26 December 2017, the United States has sent more fighters to Mosul to work side-by-side with Iraqi forces on the eastern side of the city. The US Defence Department has confirmed the implementation of US special forces operations inside Mosul. US forces are providing multifaceted support to Iraqi forces through hundreds of advisers on the battlefield and in operating rooms, missile strikes directed via satellite and intense aerial strikes launched by attack helicopters and Apache aircraft in addition to shelling with self-propelling artillery, which has played a key role in enabling the Iraqi forces to move forward.

Obstacles confronting Iraqi forces

The residential neighbourhoods in western Mosul are characterised by narrow streets and alleys, which prohibit the Iraqi forces from using armoured vehicles. The high population density is a barrier to the extensive use of long-range artillery fire and mortar shells used by US and Iraqi forces. The presence of such large numbers of people in a relatively small geographical area further complicates the widespread reliance on international coalition airstrikes, which has constituted one of the most successful factors in the recovery of cities by Iraqi troops.

The military plan for recovering western Mosul prioritises the preservation of civilian lives and properties, as well as public property and infrastructure. The Iraqi government is keen to reduce civilian casualties resulting from military operations, including through less reliance on the aerial bombardment of Iraq by the international coalition, fearing the collapse of a large number of old buildings, which make up a high proportion of the total buildings on the western side. In particular, it would like to rely less on the use of explosives with significant destructive potential, such as strategic long-range bombers or seismic bombs used to destroy tunnels, which were a factor in resolving the battle of Ramadi at the end of 2015.

The widespread use of land and aerial bombardment on the densely populated neighbourhoods of the western side may result in major displacement, exceeding the absorption and relief capacities of the Iraqi government and the United Nations mission.

The Tigris River, which bisects the city into two sides – east and west – following the destruction of its fixed bridges, has become a natural disruptive barrier to the northern axis from the battle to recover the western side. Coalition aircraft has partially destroyed five bridges connecting both sides of the city to cut off IS supplies to its fighters on the eastern side, in the hope of repairing them after the start of the western side’s recovery. However, the Islamic State has destroyed them almost beyond repair in military operations. The Iraqi forces will have to build temporary pontoon bridges to link both sides of the city after gaining a foothold on the western side, which is under IS control, making the construction of these bridges susceptible to fire by IS fighters and their artillery.

Military strategy for battle

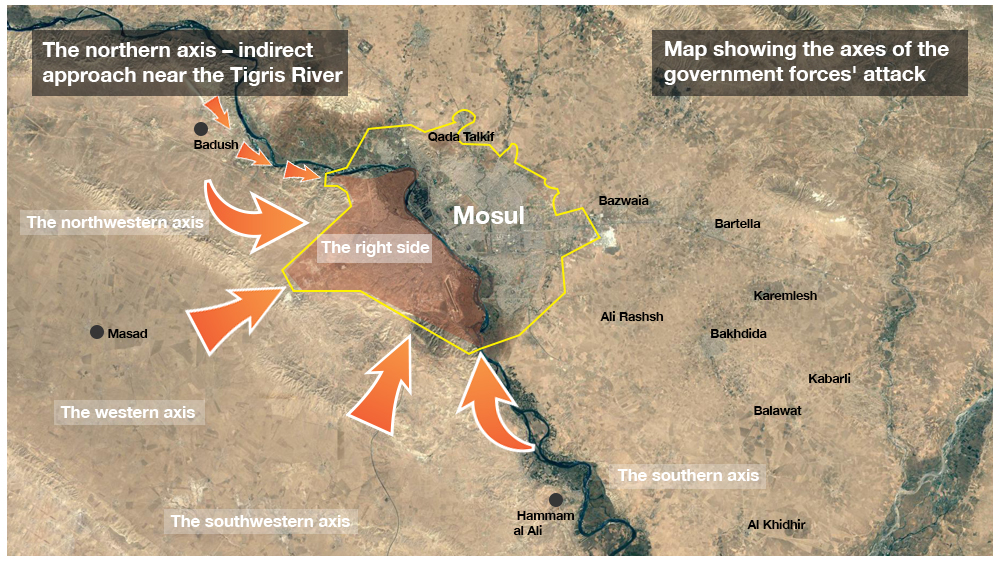

The battle for the western side is characterised by a quick success in recovered areas and reaching the residential quarters by the fifth day of the battle. Forces from various organisations have participated in the campaign, launching attacks on several fronts simultaneously across multiple axes of fighting. The same forces that participated in the eastern side are also participating in the battle for the western side, which adds to their combat experience from previous battles over more than two years.

Iraqi forces have imposed a complete blockade on all ports on the western side of Mosul.

On the northern front, Iraqi army units are stationed on the eastern side along the left bank of the Tigris River. However, on the western axis, the Popular Mobilisation Forces and units of the Iraqi army have imposed a siege to prevent the escape of IS fighters, and cut off supply routes with Anbar and Syrian cities to deprive IS fighters of the ability to manoeuvre.

On the southern axis, which is the main focus of the attack on the city, most of the offensive forces are concentrated, including anti-terrorism and rapid response forces from the federal police and Iraqi army units, with US special forces providing support and consultation as well as artillery bombardment.

During the first three days of battle, Iraqi forces successfully recovered a number of villages on the southern side. After gaining control of these villages, they achieved the battle’s most strategic military success: reaching Mosul airport, 13 kilometres south of the city, and obtaining a foothold there. On 23 February 2017, they gained control of parts of the airport, and on the next day, they gained complete control of the airport in addition to nearby Ghazlani camp as a starting point for recovering the entire right side. The two areas are open, which makes it difficult for IS to defend them in terms of confronting ground troops and intensive shelling from the air and ground.

On 25 February 2017, the battle for the western side entered a new phase, moving from open areas to residential neighbourhoods on the southern side of the city after the security forces took control of Al Ma'moun neighbourhood in the southwest of the city, which was the first residential neighbourhood entered from their bases at Mosul airport and Ghazlani camp.

With continuous intense fire by Iraqi army units stationed on the other bank of the river, an infantry unit from the rapid response forces was able to reach the fourth bridge area on 27 February 2017. The unit converged in a number of buildings at the top of the bridge to gain a foothold for other forces, which could progress alongside the river bank to secure passage for vehicles deep into the city to try to recover the fourth bridge and repair it for vehicle crossing, bring in reinforcements from the east side, and open the northern front to intensify the siege on Islamic State fighters in the neighbourhoods on the western side.

Previous events indicate that in the first days of the battle, the offensive coalition forces were able to expand their ability to manoeuvre and narrow the field of IS movement, which indicates that the balance of power has turned in the forces’ favour; and the continuation of this momentum will defeat IS.

IS options during and after the battle

The organisation’s leaders will try to exploit the population density to obstruct the Iraqi forces’ progress, prolong the combat operations and delay a military resolution in order to secure alternative sites for its leaders and fighters in Deir ez-Zor or cities of western Anbar, and move there with their families. IS is expected to defend itself similarly to the way it did in battles in the Libyan city, Sirte, where its fighters fought for several months from street to street and house to house before losing the city. Also, to some extent, it will be similar to the way it did in the battles it fought in the town of Kobani (Syrian Ayn al-Arab), which were carried out in the streets for several months under intense aerial bombardment.

However, in previous battles, IS abandoned several cities under the pressure of offensive military forces. In the final stages of these battles, IS fighters moved to other cities in order to continue combat operations. In either case, rapid advancement or tactical withdrawal, the Islamic State is expected to lose the entire city of Mosul within a period of time depending on two undetermined factors: its intentions and the coalition’s response if there is a large number of casualties in the battle. IS fighters have limited choices after losing Mosul and the remaining Iraqi cities in western Anbar.

Among the expected interim strategies for the Islamic State

First

After a series of losses of cities and areas under its control, and since losing Tikrit in early April 2015, the organisation’s strategies appear to be based on depleting the Iraqi forces’ human resources and equipment to the max through defensive battles in cities and regions before abandoning them with minimal casualties.

Second

In conjunction with the intensification of fighting on the western side of Mosul, IS has intensified its operations outside the battle fronts, targeting cities and regions far from it in a move that seems to return to the guerrilla-war style by activating sleeper cells in cities they have lost.

Third

It will concentrate in the eastern regions under its control in Syria, and the desert regions of western and north-western Iraq in camps that it used previously between 2007 and 2014, which are contiguous with the areas of the Deir ez-Zor province on the other side of the border.

Fourth

The organisation will use desert areas as a springboard to launch attacks to gain control of smaller cities and withdraw from them after achieving some of its goals, or target military convoys on the roads between cities or military barracks in addition to launching abrupt attacks.

Prospects

Almost certainly, Iraqi forces will end the battle for the recovery of the city’s western side in their favour within the coming weeks. However, this does not mean the end of IS in Iraq or its threats.

The central government will face challenges after the battle of Mosul in relation to the management of the city and power sharing between Iraq’s rival parties with their various ethnicities and religions.

To end the cycle of political conflict, violence and terrorism, the central government must confront the reasons that allowed IS to seize large areas of Iraq. These reasons relate to the demand of Sunni Arabs to manage their provinces according to what they think serves the interests of their inhabitants and be enabled to establish a force that can protect them from the abuse of Shi'a militias, the Popular Mobilisation Forces and, to some extent, the Peshmerga forces. Such a force, based on the experience of the "Awakenings", should contribute to ensuring the internal security of their cities and prevent their cities from falling under IS control for the second time, in light of the central government’s weaknesses in securing the Sunni cities.

However, we cannot say for sure that the expected loss of the entire city of Mosul and other cities in Iraq will mean the end for the Islamic State. The fighters are expected to shift to new methods of waging deadly attacks to cause the greatest losses in the ranks of the security forces as well as both the Shiite and Sunni populations. Moving to desert camps will save a lot of financial resources that were spent on managing the cities and will also provide IS with more fighters for protection and services. It is assumed that IS leaders, aware of their losses of the cities they control in Iraq, have taken measures to secure future shelter areas and store enough light and medium weapons to sustain their future activities.