The US bombing of Syria’s Shayrat air base imposed some restrictions on the Syrian regime and its allies and raised the ceiling of its opponents’ demands to remove Bashar al-Assad. However, it is still too early to regard the strike as more than a passing act or a strategic shift in the US position on the war in Syria.

Context

US President Donald Trump decided to bomb the Syrian air base during his first one hundred days in office. He certainly knows that his bombing of a Syrian military site, which the Obama administration had avoided for six years, will provoke not only Damascus but also Moscow and Tehran.

The US strike will positively impact the morale of Syrian opposition forces as well as that of Arab countries that oppose Iran and the Assad regime. However, the strike itself does not represent a strategic shift in the US approach to the Syrian crisis – at least not yet. For example, during the fifth round of the Geneva talks on Syria, it was noted that the United States is not seeking an active role in determining Syria’s future.

However, this does not mean that the strike is not a precursor to a change in Washington’s policy toward Syria. The president clearly stated the day before the strike that his position on Assad had changed, and US Secretary of State Rex Tillerson confirmed that Assad had no future in governing Syria.

Introduction

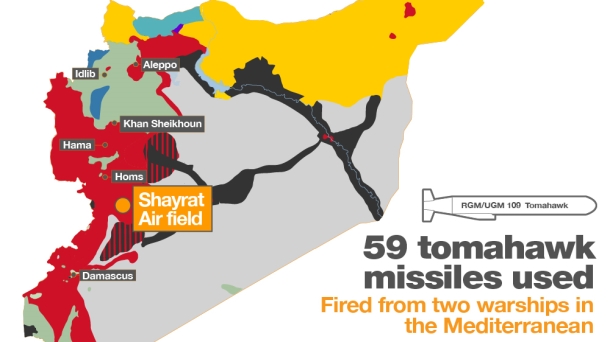

Three days after the Syrian regime bombed the city of Khan Sheikhoun with chemical weapons, Washington carried out its threat of punishment by firing missiles at Syria’s Shayrat air base near Homs, which the United States says is the source of the aircraft that carried out the chemical attack on Khan Sheikhoun.

On 4 April 2017, al-Assad’s planes dropped shells believed to be loaded with lethal sarin gas on the town of Khan Sheikhoun, a town in Idlib province in northern Syria. The chemical attack on Khan Sheikhoun killed more than eighty people from the small town and wounded dozens more. According to Syrian opposition sources, this is the second chemical attack on areas outside the regime’s control in the last month, the first of which occurred in the Damascus countryside.

Over the next two days, images of the Khan Sheikhoun attack and its victims echoed across the world. It was no secret that the language used by officials in the Trump administration, including by the president himself, to denounce what they saw as a brutal act by the Syrian regime, was sharp and alarming.

The problem of the regime’s use of chemical weapons dates back to 2013, when Russia brokered the removal of Syrian chemical weapon stockpiles in exchange for the Obama administration’s suspension of a punitive blow to the Assad regime for using chemical weapons against its own people. In August 2013, the UN Security Council issued Resolution 2118, which condemned the regime’s use of chemical weapons and stressed the prevention of Syria from manufacturing, storing and using such weapons in the future. The UN Security Council has already begun to investigate the chemical attack on Khan Sheikhoun amid a sharp divide among its members. Russia has threatened to veto a UN resolution condemning the Assad regime. The Trump administration, however, did not wait for the outcome of Security Council deliberations, or refer to Resolution 2118, when it decided to make a punitive strike against Syria’s Shayrat air base.

Why did the Assad regime carry out such a chemical attack on Khan Sheikhoun, especially since the town is neither a battlefield nor is located on a fighting front? Why did the Trump administration decide to launch a punitive attack against the Assad regime for the first time since the beginning of the Syrian crisis over six years ago? What are the effects of the US move on the Syrian crisis and international as well as regional engagement in the Syrian crisis?

Chemical Attack Calculations

The Syrian regime, including Foreign Minister Walid Muallem, who has long been absent from the scene, denied responsibility for the attack on Khan Sheikhoun. The regime claimed that the incident resulted from Syrian aircraft bombing sites of Ahrar al-Sham (formerly al-Nusra and its allies), which were, according to them, storage sites for chemical weapons. However, the United States says it is sure that the regime’s planes carried out the chemical attack on the town and it has the evidence. In addition, experts say that the regime’s narrative is not entirely believable. First, sarin gas is derived from unstable material; it is not stored for long periods, and the materials used to generate it are usually mixed directly before its use. Second, the gas, even if it were stored somewhere in the town, requires a severe thermal explosion to be dispersed; spreading from a storage site is usually limited and does not cause significant casualties.

The important question now is: If the US accusation of Damascus is true, then why did the Assad regime bomb a town that is not a battlefield and not necessarily a strategic location with chemical weapons? This question requires a response on several levels. On the first level, the Assad regime and its allies seem to have been very reassured recently about its international status. Just a few days before the attack on Khan Sheikhoun, the US Ambassador to the United Nations, Nikki Haley, said, “President Trump’s administration does not consider the overthrow of the Assad regime a priority.” The regime in Damascus knows that Trump’s main aides, including Steve Bannon (before he was sacked), have never concealed their convictions that the Syrian opposition is not promising, and that the solution to the Syrian crisis is to allow the Assad regime to win. The Assad regime, in short, was considerably relieved by Trump’s approach to the Syrian crisis, or rather by the remarkable absence of its approach, and thus became freer in its war against its people and opponents.

This, however, is not necessarily sufficient to explain why Khan Sheikhoun was chosen as a target. The Assad regime has certainly shown a great deal of irrationality over the past six years, but even its usual irrationality does not provide an explanation for the bombing of a small town of only 50,000 people that is relatively far from the front lines with chemical weapons.

In fact, the regime has been following a policy of displacing as many Sunni Arab Syrians as possible from all areas that its army’s arsenals reach, not only from areas considered to be a strategic threat, such as the Damascus countryside. The regime has been working on displacing the predominantly Sunni Arabs of Aleppo and is now working to displace the largest number of people in Homs. It is conceivable that bombing a town like Khan Sheikhoun could encourage more Idlib Arabs to migrate, especially after the province became a refuge for large numbers of Syrians who were forced to leave the cities of Aleppo and Homs and the Damascus countryside. Khan Sheikhoun, the last town in the province of Idlib on the road to Hama, whose countryside is gripped by fierce battles, has inflicted heavy losses on the regime and its Shi'a militias in the past few weeks. It seems that the regime believes that the town has become the main starting point for rebel forces fighting in the battles of Hama.

Whatever the case, the attack on Khan Sheikhoun must be seen as a disaster not only for the Assad regime but also for Russia. A chemical weapon attack could not happened without the Syrian president’s approval. It is assumed that Russia is not only playing a major role, militarily and politically, in protecting the Assad regime, but is also the most important partner in Syrian decision making, if not the first. If al-Assad took a unilateral decision to use chemical weapons, then he would be ignoring his Russian ally, which was already the sponsor of the 2013 agreement to disarm Syria. In other words, al-Assad seems, after all Russia has done for him, to have an underlying willingness to turn his back on his Russian allies, revealing them only as temporary.

The other possibility, of course, is that Russia was aware of the attack on Khan Sheikhoun, and perhaps it helped the regime regain its chemical weapon capability over the last few years, or refrained from preventing it from retaining some of its capabilities in this area since the 2013 agreement. This prospect is the weakest, and there are no concrete indications yet. The United States has already begun an investigation into whether Russia was a partner in the Khan Sheikhoun attack.

US Punishment

President Trump made his decision to bomb the Syrian air base within the first one hundred days of his term. He came to the White House under the slogan ‘America First’ – which he raised with the highest possible voice throughout his election campaign and after taking office – which implies his indifference to being what he described in an interview as ‘president of the world’. Undoubtedly, the US president knows that his bombing of a Syrian military site, which the Obama administration had avoided for six years, will have repercussions not only in Damascus but also in Moscow and Tehran. Above all, Trump made the decision to express a punitive warning to the Assad regime without trying to obtain international cover. So why did the new president in the White House make such a decision and in such a way?

A day before bombing Syria’s Shayrat air base, Trump revealed in a press conference with King Abdullah II that the scenes of the victims of Khan Sheikhoun’s attack, especially the children, had affected him. This personal reaction may be the reason behind the swift decision to punish the Assad regime for violating its international commitments. However, the problem is that the Syrian people have been victims for years. Their fall did not have the effect of pushing the United States to act, not even under the Obama administration, which always presented itself as the most humane and caring in the world.

A number of motives, domestic and international, must have weighed in the president’s balance when he decided to launch a military strike on the Assad regime.

At the local level, although the president’s popular base is opposed to any active US role on the international stage, Trump’s administration suffers from repeated failure to implement its agenda, and polls show low ratings for the president at the start of his term. More importantly, the issue of the relationship between the Trump campaign and Russia continues to pursue the president and his administration in a way that threatens his ability to act and exercise his duties. Taking a bold step in foreign policy – the area that is always described as the most important in shaping the president’s image – will not only help the president to strengthen his position and leadership, but will also help defeat rumours about his campaign’s relationship with Russia regardless of the external reaction in Russia and elsewhere.

At the international level, Trump’s approach to the Syrian regime must be read as an occasion to direct several messages at once: The first message, of course, is to the Syrian regime and its closest allies in Iran and Russia. Trump wants to say that the United States will not exit the Syrian crisis and that even before the establishment of a clear policy on Syria, it cannot be assumed to have abandoned its role in determining the fate of the most complex and costly crisis since the end of the Cold War. In addition, it is clear that the Trump team sees that in the past years, Washington has allowed what it should have never allowed, the expansion of Russia and Iran, and that the time has come to put an end to it.

The other message is certainly directed at the North Korean regime, which includes an open warning that Washington will not hesitate to use force to protect its security and the security of its allies even without international legal cover.

The third message makes it clear that Washington’s relations with its western allies, with the exception of the United Kingdom, have been strained since Trump took office whether with regard to differences over NATO defence budgets, the negative position on European unity of Trump and some of his allies, or the criticism by Berlin and Paris of Trump’s non-liberal attitudes towards international trade and immigrants. Trump wants to say to his allies that the United States is still at the forefront of international affairs, and only it can defend Western values in the world.

Finally, the US strike on the Syrian regime must lead us to reconsider the nature of Trump’s administration and what policies it might adopt. The problem of how to read the Trump administration in Washington stems from Trump’s aggressive campaign slogans, which many consider to define his policies at home and abroad. The truth, of course, is that no US president is the sole creator of his own convictions, but that his presidential term is also affected by structural influences: the balance of US government institutions, the constants of the state during his tenure, the experiences of his key allies and the sudden crises he faces. During his three months in office, President Trump has been no exception, and the slogans he has raised during his election campaign, whether or not they were understood as isolationist tendencies, will have the least impact in shaping his policies.

Broad Support and Strict Rejection

It is noteworthy that although the US decision was made unilaterally, the blow to the Syrian air base has aroused widespread support. Various Syrian opposition parties as well as all Western European and Gulf Arab countries supported the US step. Europe welcomed the US move, perhaps because of the new direction of the Trump administration, particularly in terms of readiness to confront Russia. The Arab Gulf states must have looked at Trump’s move not only as a more active US role in the Syrian crisis but also, more importantly, as emphasis on the credibility of Trump’s previous declarations of its determination to counter Iran’s regional expansion.

Iraq, among the Arab countries concerned with the Syrian crisis, has avoided supporting the blow to the Syrian regime in view of Iran’s deep influence on the Iraqi state and its political circles. Egypt issued a vague statement showing neither conviction nor support. Its position must be understood not only in terms of sympathy for the Syrian regime but also in light of the outcome of President el-Sisi’s visit to Washington, which was limited to expressions of friendliness and support and totally lacking of essential US support for the Sisi regime and Egypt’s struggling economy.

Turkey, the country in the region most closely linked to the Syrian crisis, has shown clear and unequivocal support for Trump’s move and has confirmed its willingness to cooperate with him in Syria. However, Ankara also recognised the limited nature of the US move and called for further punitive measures towards the Syrian regime and the establishment of safe areas to protect Syrian civilians.

On the other hand, Iran condemned the US operation and described it as terrorism. However, being in a state of anticipation of Trump’s policy towards the country, it has gone no further. The Russian reaction was multifaceted; Russia certainly understood that Trump’s move was a direct insult to their role and position in Syria. Although its intransigence in Security Council deliberations directly contributed to Trump’s decision to punish the Assad regime, it continued to deny al-Assad’s responsibility for the chemical attack, describing the US strike as illegal and claiming that it directly served the forces of terrorism in Syria and undermined the peace processes in Geneva and Astana. Within hours of the Shayrat airbase bombing, Moscow announced the suspension of its agreement with the United States on airspace deconfliction over Syria, which coordinates Russian and US flights in Syrian airspace, and announced its intention to strengthen its defence supplies to the Syrian regime.

However, Russia’s reactions remain limited and avoided open confrontation. What cannot be clearly seen now is whether Russia is starting to prepare for a different US role in Syria, and the nature of what the Russians are already saying to the Assad regime and the Iranians, if Moscow, like Washington, is sure of the Syrian regime’s responsibility for the attack on Khan Sheikhoun.

Implications of the US move

The US strike on Syria’s Shayrat airbase will have a positive impact on the morale of Syrian opposition forces as well as that of Arab countries opposed to Iran and the Assad regime. However, the Shayrat airbase strike does not represent a strategic change in the US approach to the Syrian crisis per se – at least not yet. Clearly, both the defence minister and the national security secretary presented the president with more influential options, such as bombing the presidential palace in Damascus or destroying a number of Syrian air bases simultaneously, but Trump decided to strike a limited blow to the base from which the aircraft that attacked Khan Sheikhoun took off. In other words, the US president has taken a small step at the military level with more symbolic dimensions at the political level.

It is clear that the Trump administration has not developed a specific strategy for its policy in Syria or the Middle East as a whole. During the lengthy fifth round of the Geneva talks on Syria, it was noticeable that the United States was not seeking an active role in deciding Syria’s future. Despite repeated US-Turkish meetings since January 2017, there has been no suggestion that Trump’s administration is adopting a significantly different Syrian policy from Obama’s, whether regarding the Assad regime or the priority of fighting the Islamic State and the alliance with the Kurdistan Democratic Party in this war. Despite Trump’s comments on a safe zone in Syria, there is no sign that Washington has actually begun preparations to create such areas.

However, this does not mean that the strike on the Assad regime is not a precursor to a change in Washington’s policy toward Syria. The president clearly said the day before the strike that his position on al-Assad had changed; and in a press conference on 6 April, Secretary of State Rex Tillerson stressed that there is no future for al-Assad in Syria, backing away from the statements made by his delegate at the United Nations. Such a change comes from an increase in the leverage of members of Trump’s cabinet and military and intelligence leaders, such as the Secretary of Defence, the Head of the Central Intelligence Agency and the Secretary of the National Security Council, who seem to outweigh the president’s far-right allies when deciding to strike the al-Assad regime.

It is not yet certain to what degree this change will take place. There are indications that Washington is taking a different direction in Syria and throughout the Middle East, indicated, for example, by the declaration of Shi'a militias supporting the Assad regime terrorist groups, striking Hezbollah camps in Syria, or pledging to play a more effective role in the Geneva talks. This follows a clear interpretation of the first Geneva agreement that Bashar al-Assad should step down as a prelude to any settlement of the Syrian crisis, or begin to work towards the establishment of safe zones in northern or southern Syria. It is also necessary to wait and see how the Trump administration will face Iranian expansion in the Arab region, particularly Iraq, Syria and Yemen. Until such indications emerge, the impact of the US strike on Shayrat airbase on the course of the Syrian crisis as well as on the fierce scramble between Iran and its Arab neighbours should not be overestimated.