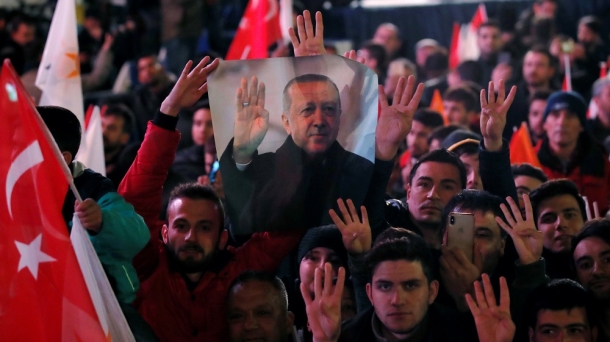

The municipal elections in Turkey on 31 March 2019 were one of the most hotly contested polls in decades. President Recep Tayyip Erdogan alone held 80 campaign rallies in 50 cities. While municipal administrations have no political power, municipalities are nevertheless the place where political parties and voters have the closest direct contact. For opposition parties and politicians, it is one of the few places where they can prove their mettle and skill. Many Justice and Development Party (AKP) cadres—including famously, Erdogan himself—got their start on the municipal level.

For the ruling AKP, this election was significant for another reason. The constitutional amendments it sponsored passed with a bare majority in 2017 and were rejected outright by voters in the major cities. In the 2018 elections, Erdogan held on to the presidency by a slim margin while his party lost their parliamentary majority. With no more elections slated until 2023, this was the AKP’s last chance for some time to test its popular support and demonstrate its continued appeal across class, geographic and ethnic lines.

The elections were contested by two major coalitions: on one side, the AKP and the conservative Nationalist Movement Party (MHP), the AKP’s coalition partner in the 2018 elections; on the other, the center-left Republican People’s Party (CHP), the main opposition party, and the Good Party, a relatively new conservative, nationalist party formed by a breakaway faction of the MHP. Several other smaller parties competed as well, most importantly the Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP), a Kurdish nationalist party that has been severely weakened by arrests and other state-directed actions against its leaders and cadres taken amid Turkey’s escalating conflict with the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK).

In the 2014 municipal elections, the AKP did particularly well, beating predictions that its fortunes would be adversely affected by the then-incipient conflict with the Gulenists. Overall, the AKP came away with 45 percent of votes, taking 18 of the mayoral positions in Turkey’s 30 biggest cities and three of the mayoralties in the five major metropolitan areas. Its closest runner up, the CHP, took 28 percent of the total votes and won six mayoralties in the 30 biggest cities.

At 84 percent, turnout in this year’s poll exceeded all other municipal elections. Preliminary results show that 45 percent of the electorate voted for AKP candidates, followed by 30 percent for the CHP, 7.4 percent for the Good Party, and 6.8 percent for the MHP.

Although these totals show the AKP holding steady, when seen from a different, more granular perspective, they are less reassuring for the party. As of writing, the Istanbul mayor’s race remains a toss-up between the AKP and CHP. The AKP also lost the mayoralty of Ankara, while its ally lost the mayoralty of Adana, formerly an MHP stronghold. In other words, the AKP and MHP went into the race holding the mayorship in four of Turkey’s five major cities and came out of it with only one—and that by just a nose.

Looking at the 30 biggest cities, the AKP went from holding 18 to 15 mayorships and the MHP from three to one.

In better news for the AKP, it maintained relatively high support in Kurdish-majority areas in the southeast, thwarting expectations, and it still holds a majority on the city councils of Ankara and Istanbul, as well as half of all city councils around the country.

In contrast, the Kurdish nationalist vote in Istanbul—nearly 2 million Turks in the city are of Kurdish extraction—went overwhelmingly to the CHP candidate, and could be a prime factor for the deadlocked race.

Overall, the AKP’s vote share in the 30 biggest cities declined from 2014, continuing a trend seen first in the 2017 referendum. The reversal in AKP fortunes is most evident in Istanbul, often considered a microcosm of Turkey. The place where Erdogan got his political start, the mayoralty of the city has been in AKP hands since the party was founded in 2001.

These disaffected voters are diverse: some belong to the well-educated, urban, conservative professional class. Others are liberals who had previously seen the AKP as a bulwark against military intervention in politics. And others are Islamists who are increasingly dissatisfied with the direction of the AKP. The change in AKP rhetoric and attitudes is certainly part of what has alienated some former AKP supporters. Since Turkey resumed its conflict with the PKK, the AKP has become more stridently nationalist, a trend that has only increased with its alliance with the MHP.

That the ruling party conducted fair, transparent elections should count in its favour. But now it should begin to reassess its policies and electoral strategies if it hopes to do better the next time.

*This is a summary of a policy brief originally written in Arabic, available here:

http://studies.aljazeera.net/ar/positionestimate/2019/04/190402063054950.html